#701 Nine years of northern nursing

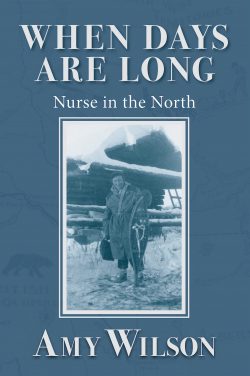

When Days are Long: Nurse in the North

by Amy Wilson, with an introduction by Laurel Deedrick-Mayne

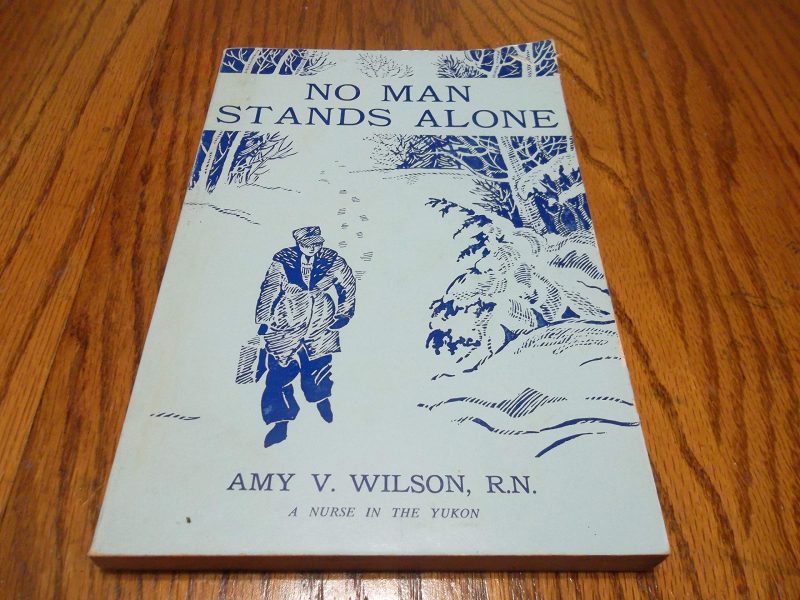

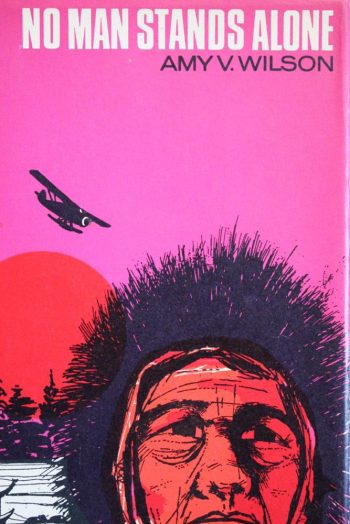

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2019. First published in Sidney by Gray’s Publishing, 1965

$24.95 / 9781773860084

Reviewed by Heather Longworth Sjoblom

*

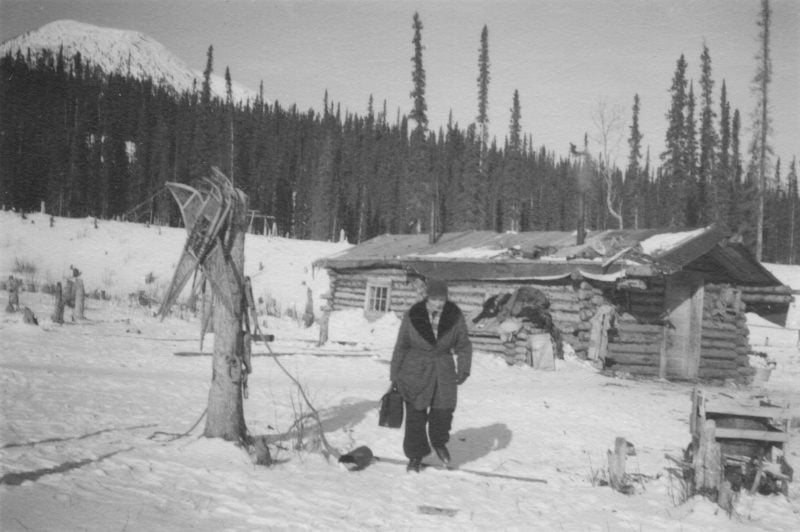

“Such a challenge! And I couldn’t resist it,” wrote Amy Wilson about her acceptance as field nurse for 3,000 Indigenous People along the Alaska Highway in northeastern British Columbia and the Yukon. Most people in 1949 would have been aghast at taking a job that covered an area of 2,200 square miles that was difficult to access at the best of times, but Wilson was intrigued.

“Such a challenge! And I couldn’t resist it,” wrote Amy Wilson about her acceptance as field nurse for 3,000 Indigenous People along the Alaska Highway in northeastern British Columbia and the Yukon. Most people in 1949 would have been aghast at taking a job that covered an area of 2,200 square miles that was difficult to access at the best of times, but Wilson was intrigued.

Wilson held this position from 1949 to 1958 and her memoirs focus on the challenges of the first two years. When Days Are Long: Nurse in the North is an updated edition of Wilson’s No Man Stands Alone (first published in 1965). It includes a new introduction by Wilson’s grandniece, Laurel Deedrick-Mayne, along with a new foreword and several photographs.

Wilson’s quality of writing draws the reader into the story. She shares her worries about travel, concern for her patients, challenges, and triumphs with a sense of humour and an intrepid spirit. Many chapters of the book develop into real page-turners where the reader just has to find out how a particular episode ends!

Present in Wilson’s story is both a divide between white settlers and Indigenous people and a willingness to work together. For example, when undertaking Operation Toxoid, a mission to inoculate every person living along the Alaska Highway from diphtheria, the British Columbia health authority dictated that the provincial public health nurse, Miss Bond, should immunize “whites” while Wilson immunized Indigenous people. However, the two women didn’t see it like that. Each night, they played three games of cribbage. The winner — and they were pretty equally matched — had her choice of filling syringes or administering the toxoid the next day.

A cooperative human spirit often prevailed in the north. Many fur traders, bush pilots, and Royal Canadian Mounted Policemen were more than willing to go out of their way to help Wilson access remote Indigenous communities in desperate need of medical services, sometimes even risking their own lives to do so and proving, truly, that no one stands alone in the north.

As Laurel Deedrick-Mayne points out in the introduction, many of the issues Wilson encountered are still present today. Many Indigenous people across Canada still don’t have access to clean water. There is still lack of access to schooling and Indigenous people often have to leave home to access higher education. Though the Indian Residential Schools and Indian Day Schools that Wilson writes about are now closed, Indigenous communities are dealing with the repercussions of these institutions, from loss of language and culture to emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. Indigenous Canadians still lack easy access to health care. Just as in Wilson’s day, they have to travel to urban centres (often in southern Canada) for treatment. They are sometimes lonely, isolated from their families, and suffer from depression. Many of the diseases Wilson encountered and worked to eradicate, such as measles, are making a comeback. Wilson’s stories are even more relevant now, over fifty years after they were first published.

This new edition of Wilson’s memoirs is not very different from the original. The new introduction by Deedrick-Mayne, though interesting and insightful, is only a brief three pages. What is significant about this reprint is that it introduces Wilson’s experiences to a new generation and once again raises the questions: why do Indigenous people still have to deal with such health crises today and what can we do to improve these situations?

*

Heather Longworth Sjoblom is the manager and curator of the Fort St. John North Peace Museum. She has a BA (Honours) in history from Acadia University, an MA in history from the University of Victoria, and a Post-Graduate Certificate in Museum Management and Curatorship from Fleming College. The Alaska Highway has captivated Heather for years, especially stories about mosquitoes during the highway’s construction. As an environmental historian, Heather loves researching relationships between people and nature and working them into museum exhibits and programs. She also enjoys gardening, hiking, travelling, and spending time with her husband and son.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.