#699 Reply to a cenotaph

Once Well Beloved: Remembering a British Columbia Great War Sacrifice

by Michael Sasges

Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum Press, 2019

$17.95 / 9780772672551

Reviewed by Sylvia Crooks

*

The national trauma of the First World War, even though it was fought over one hundred years ago, is still deeply felt today. Michael Sasges’ Once Well Beloved is a compelling local history and another testament to the devastation of that war on the lives of families and communities.

The national trauma of the First World War, even though it was fought over one hundred years ago, is still deeply felt today. Michael Sasges’ Once Well Beloved is a compelling local history and another testament to the devastation of that war on the lives of families and communities.

Canadians entered the war full of enthusiasm to defend country and Empire, not able to imagine the horror that was to come. British Columbians rallied to the call in 1914 in greater proportion that in any other part of Canada. According to Sasges, 90 of every 1000 BC residents volunteered, compared to 75 in the prairies and Ontario and 50 in the Maritimes. The losses devastated small communities across the province, even leaving some as ghost towns. Although their experiences are similar in so many respects, each BC community has its own war story to tell, and Sasges provides a good model of how to respond fittingly to the distressingly long lists of names on Great War cenotaphs.

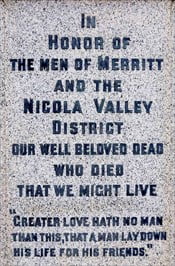

On the granite cenotaph in the city of Merritt are the names of 44 men from the surrounding Nicola Valley who lost their lives in that war. Inscribed on the cenotaph are the words, Our well beloved dead who died that we might live. Sasges, a former director of the Nicola Valley Museum, was inspired to write this book after undertaking research on Nicola Valley history for a thesis at Simon Fraser University, published in 2013. He writes movingly and in some depth about twelve of the men remembered on the cenotaph, “ordinary men” remembered “as soldiers, mostly, but also as men with birthplaces, usually distant, and competencies, mostly now lost.” The men profiled are carefully selected as “representatives of their time and place.” Most were born in the British Isles and had previous military experience, typical of BC recruits, and many were miners in the thriving coal mines of the Nicola Valley.

Between 1900 and 1910 the population of Merritt more than quadrupled after the Canadian Pacific Railway built a connecting line from the mainline at Spence’s Bridge in 1906, providing easy access to the nearby coal deposits. An influx of young men and families from the coal fields of the British Isles changed the demographics of the area and created tensions with the Indigenous people who had been the majority population in the Nicola Valley, and whose way of life was overturned.

The soldiers Sasges profiles are representative of different periods of the four-year conflict: three were victims early in the war, in 1915; six lost their lives in the middle years, on the Somme in 1916, and in 1917 in battles for Vimy Ridge; two were lost in the last days of the war in 1918; and one was a victim of the Spanish Influenza in 1919.

The soldiers Sasges profiles are representative of different periods of the four-year conflict: three were victims early in the war, in 1915; six lost their lives in the middle years, on the Somme in 1916, and in 1917 in battles for Vimy Ridge; two were lost in the last days of the war in 1918; and one was a victim of the Spanish Influenza in 1919.

The first to die was Lance Corporal Robert Davidson, a 41-year-old coal miner, a Scot who had served for ten years in the British Army Highlanders. He was killed in action in April 1915 in the Second Battle of Ypres in which the Canadians were victims of the first gas attack on the western front. “Something hellish” is how a soldier in a letter home described a gas attack. “Any one who gets a good dose dies in agony, and any one who gets a small dose lives in agony.”

Davidson left a wife and two sons. Like so many who died in ground continually under fire for four years, his body was never found and he is remembered on the Menin Gate memorial.

Davidson left a wife and two sons. Like so many who died in ground continually under fire for four years, his body was never found and he is remembered on the Menin Gate memorial.

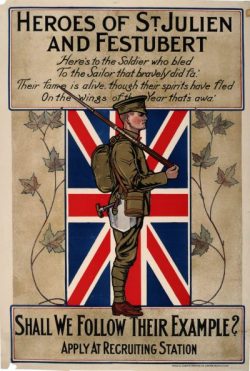

The other two men Sages profiles who died in 1915 were killed in a bayonet attack on the same day in May in the deadly Battle of Festubert, the second major battle fought by the Canadians in the war. Private John “Jack” Birch was a 33-year-old carpenter, originally from Manchester in England. He was shot through the head and killed instantly “just after he had gained a footing in the German trench.” Sasges notes that the Canadian military did not begin issuing helmets to its soldiers until the spring of 1916. Corporal John McGee, another Scot, had served for seven years in a British Highland regiment. When asked on his attestation papers for his trade or profession he answered, “None.” Sasges calls him a drifter, “who probably worked for wages when he had to.”

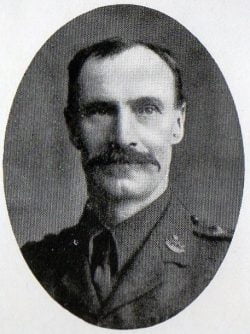

Captain John “Jack” Foster Paton Nash is the only officer among the men featured in the book. A Londoner and Boer War veteran, he was killed in April 1916, two days after his 50th birthday. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his courage at Festubert in repairing telephone wires while under heavy fire. Nash was held in high regard in Merritt, was a fire warden and later game warden, and was active in local politics. He was a pioneer of the Nicola Valley, having lived there from at least 1886. He married his wife Eleanor only ten days before he left for training at Valcartier, and although she moved to England to be nearer to him, they had only weeks together of married life.

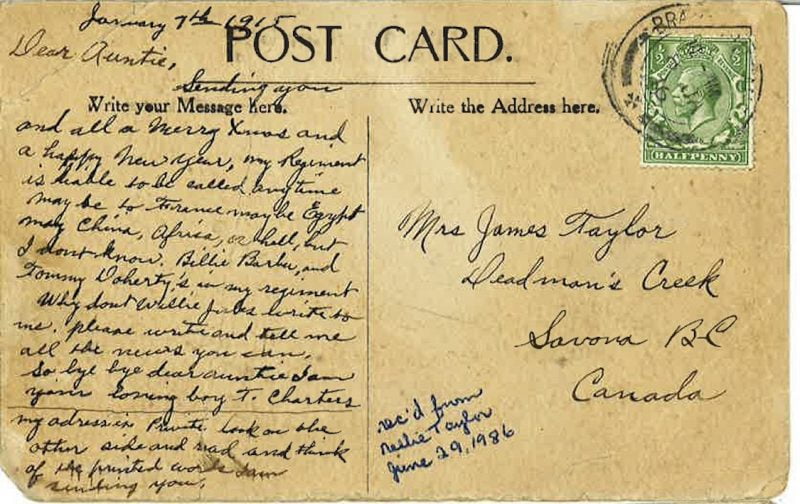

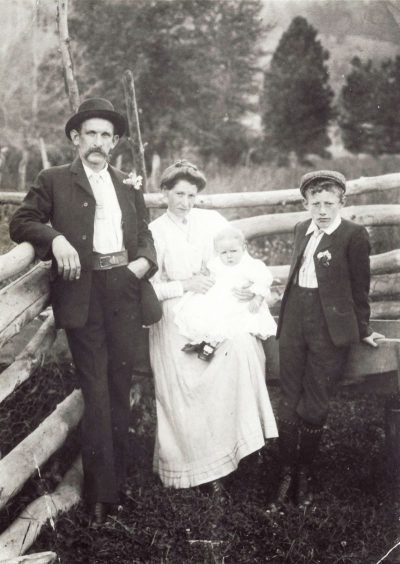

Another of the twelve “well beloved” is Tommy Charters, a young Indigenous cowboy who died on the Somme in 1916. Among Indigenous people of the Nicola Valley the horse was an essential part of life, and Tommy reflected this. He was a cowboy who trained horses and also competed in rodeos. He did not take easily to military discipline; he was frequently punished for drunkenness and insubordination, and “passed 10 of his last days in France enduring field punishment.” Sasges calls Tommy Charters “Nicola Valley’s best and worst remembered Great War sacrifice.”

The name of Charters is remembered on a “roll of honour” in the local Anglican Church and also in the First World War Book of Remembrance in Ottawa, but not on the Merritt cenotaph. The name “T. Tilamoose” on the cenotaph is similar to the name of Tommy’s father, so most likely it refers to Tommy. Cenotaphs are notorious for mis-spellings and other bits of misinformation, lacking any standards or guidelines when they were erected.

“The Nicola Valley’s most distinguished soldier” was also a cowboy, of mixed Indigenous and settler descent, George McLean, who earned a Distinguished Conduct Medal at Vimy Ridge for “conspicuous gallantry.” McLean survived the war.

Four of the men profiled in the book died during the battles for Vimy Ridge in 1917. Private David Hogg and his uncle, Private Alexander Hogg, were members of a coal-mining family from the Tyneside in England. David died in one of many reconnaissance trench raids carried out in preparation for the attack on Vimy Ridge. Of the 100 Canadians who carried out the raid, 58 were killed, wounded or missing. David was 23 years old when he died. His uncle, Alexander, died on Hill 120, known as “the Pimple,” the day after the taking of the hill, which was the final battle to secure Vimy Ridge. A report of the deaths of David and Alexander appeared together on the front page of the local newspaper. Influenced by their Methodist background, the Hogg family were notable in the Valley for their support of such social issues as worker safety, universal male suffrage, and temperance.

Norwegian-born Private Ingebrigt Busk was killed 55 miles from Vimy when he was hit by a train while walking on the tracks. He was one of thousands of soldiers in railway and labour battalions who supported the Canadian troops assembled for the attack on Vimy Ridge. Private John McInulty, another Scottish coal miner, was the only one of the four Vimy casualties to die in the actual attack on April 9.

“There is a certain poignance when a young soldier survives all his regiment’s battles but the last,” wrotes Sasges. So it was for Private Norman Foster Lindsay and Sapper John Paul, both of whom died just weeks before the end of the war. Lindsay had fought with a machine-gun brigade for three years before he died on October 31, 1918. “How Norman Lindsay endured the battlefields of Belgium and France for so long without losing his mind will never be known,” writes Sasges. He had been twice wounded before he was killed, and had been awarded the Military Medal. John Paul served with the Canadian Railway Troops, and was killed by a single enemy shell that landed near the light rail line he had been working on in late September 1918. A coal miner from Scotland, he left a wife and six children.

The last of the twelve men to die, Private Fred King, died in March 1919, a victim of the Spanish Influenza that reportedly killed some 50,000 Canadians. Sasges calls Fred King “an intriguing but unknowable man.” Fred King was probably an alias, and he was likely Italian in origin. He served with the Canadian Forestry Corps, comprised of loggers, sawyers, road-builders, and teamsters.

The “Flu” was devastating for the Nicola Valley, especially for Indigenous people, when as many as one in six died of “Flu” complications. Sasges gives an interesting account of how the Indigenous community resented not being able to treat their sick with their own medicinal remedies.

The appearance of Once Well Beloved is deceptive. It is a slim volume of 134 pages, from front to back. But it is packed with information, not only about the twelve “well beloved” and their families, but also covering the geography, early history, resource management, and industrial development of Merritt and the Nicola Valley. This is largely because of copious endnotes which actually comprise an annotated bibliography, so helpful to genealogists and historians. Illustrations and maps enhance the book, as does an excellent index.

Michael Sasges is to be congratulated on his extensive research, in archives, military records, contemporaneous newspaper accounts, and interviews. His Once Well Beloved: Remembering a British Columbia Great War Sacrifice is a fine contribution to the history of British Columbia.

*

Sylvia Crooks (née Shorthouse) was born and raised in Nelson. She was a faculty member of the UBC School of Library, Archival and Information Studies for sixteen years where she taught library reference and outreach services. She is the author of Homefront & Battlefront: Nelson BC in World War II (Granville Island, 2005), and Names on a Cenotaph: Kootenay Lake Men in World War I (Granville Island, 2014). She makes her home in Vancouver.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.