#685 Tracking the Komagata Maru

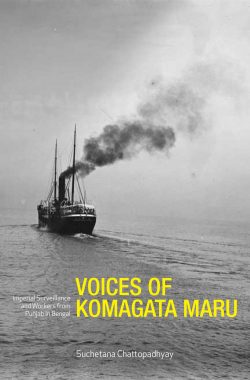

Voices of Komagata Maru: Imperial Surveillance and Workers from Punjab in Bengal

by Suchetana Chattopadhyay

New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2018; New York: Columbia University Press, 2019

$35.00 (U.S.) / 9788193401583

Reviewed by Larry Hannant

*

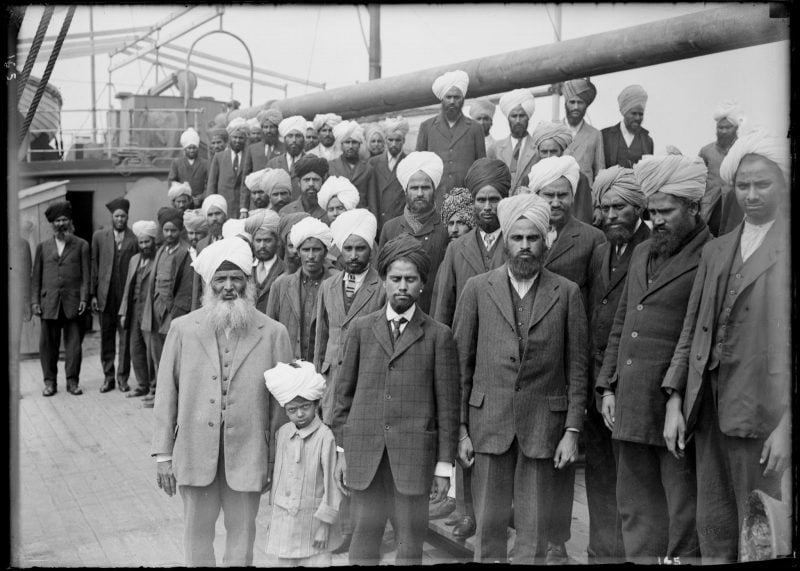

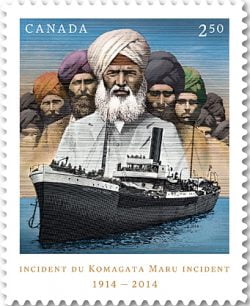

Many Canadians became aware of the name Komagata Maru only in 2016, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, still in his sunny reconciliatory phase, apologized in the House of Commons for this country’s unabashed act of racial exclusion in the summer of 1914. Referring to the 376 men — all from British-ruled India, most of them Sikhs — on board the Japanese-registered Komagata Maru, Trudeau declared that “no words can erase the pain and suffering they experienced” when they were denied entry to Canada.

Many Canadians became aware of the name Komagata Maru only in 2016, when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, still in his sunny reconciliatory phase, apologized in the House of Commons for this country’s unabashed act of racial exclusion in the summer of 1914. Referring to the 376 men — all from British-ruled India, most of them Sikhs — on board the Japanese-registered Komagata Maru, Trudeau declared that “no words can erase the pain and suffering they experienced” when they were denied entry to Canada.

The ship had been chartered by a group of Sikhs led by Gurdit Singh and had sailed from Hong Kong with the express purpose of challenging Canada’s open discrimination against non-white immigrants from India. When the Komagata Maru arrived in the port of Vancouver, a Canadian gunboat refused to let it dock. For two months the passengers endured privation on board and vituperation from the city’s press as their legal case dragged through Canadian courts, which ruled against the would-be migrants.

The most-enduring photo of the traumatic confrontation — which graces the cover of this and other books on the subject — is of the Komagata Maru steaming west into the open Pacific Ocean, bound for an unknown fate. Preoccupied with the First World War, into which the world would descend a week later, most Canadians happily forgot the ship, its passengers, and the standoff that so bluntly exposed the racial discrimination at the core of this country.

Suchetana Chattopadhyay takes up the story of the Komagata Maru at its point of departure, as Canadians were exulting in the ship’s passing from their shores and their memory. Voices of Komagata Maru sets out “to trace the last stretch of the journey of its passengers after they touched land [in India] … and to find the resonance of their actions” over the next two decades (p. 1).

While most of what Chattopadhyay describes takes place in the state of Bengal, especially the city of Calcutta (now Kolkata), where so many Sikhs congregated in the last decades of the British Raj, the Komagata Maru is properly seen as a vessel that charts a transnational journey with a corresponding tale. In order to engage it in all its complexity, Chattopadhyay is obliged to return to what had come before the dramatic confrontation in Burrard Inlet. What she unveils is a vivid illustration of the power of capitalism and colonialism in the 19th and early 20th centuries. She follows the exodus of displaced Sikh peasants from Punjab in northwest India first to the south-Indian industrial city of Calcutta. Some of them then venture out to plant the seeds of Indian communities throughout south Asia and, as industrial workers, to inhabit a vast swath of western North America. Some return west again to an India roiled by the early 20th century surge of anti-British and leftist insurgency. Always in motion, their democratic politics become a legacy they deposit along the way.

Ironically, the activists who dared to traverse the Pacific Ocean to challenge racial exclusion and found themselves shut out of Canada also learned, on route home, that British authorities, who were uncertain about the loyalty of the colony of India in the tense early months of the First World War, “were determined not to allow the ship to reach Calcutta” (p. 20). In the early months of the war the city had plunged into “an apocalyptic mood” (p. 14) as the German cruiser Emden effortlessly laid waste to British shipping in the Bay of Bengal, as popular grievances escalated over rising living costs, and as the arrival of bigoted British troops sparked tensions with locals. All this was complicated by what Chattopadhyay calls “the Ghadar effect” — the spirit of Indian anti-colonial revolt — which was bolstered by the arrival of the Komagata Maru.

Ironically, the activists who dared to traverse the Pacific Ocean to challenge racial exclusion and found themselves shut out of Canada also learned, on route home, that British authorities, who were uncertain about the loyalty of the colony of India in the tense early months of the First World War, “were determined not to allow the ship to reach Calcutta” (p. 20). In the early months of the war the city had plunged into “an apocalyptic mood” (p. 14) as the German cruiser Emden effortlessly laid waste to British shipping in the Bay of Bengal, as popular grievances escalated over rising living costs, and as the arrival of bigoted British troops sparked tensions with locals. All this was complicated by what Chattopadhyay calls “the Ghadar effect” — the spirit of Indian anti-colonial revolt — which was bolstered by the arrival of the Komagata Maru.

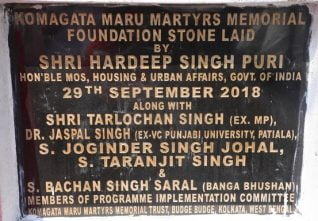

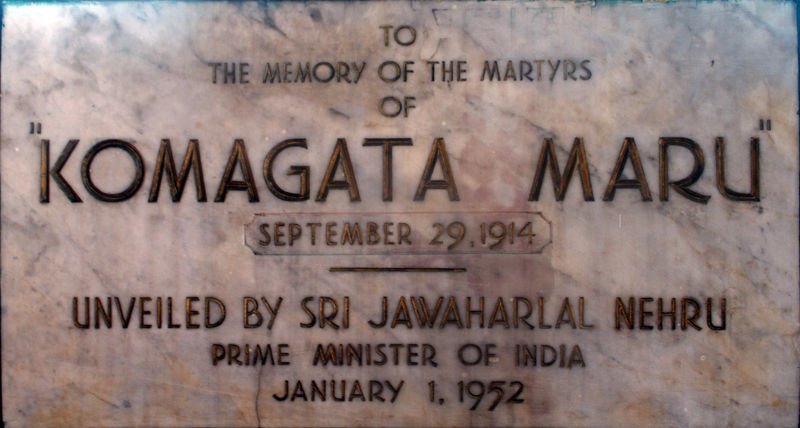

The massacre that ensued at Budge Budge, 20 kilometers south of Calcutta, exposed British authorities’ state of paranoia and determination to prevent Ghadar from taking hold in Bengal. Halting the ship outside of Calcutta, on 29 September 1914 British police and military attempted to arrest Gurdit Singh, whom they claimed was the instigator of the subversive Komagata Maru challenge. What Chattopadhyay rather mildly describes as “coercive tactics” (p. 24) by the British resulted in a riot that some have insisted was nothing less than a massacre — twenty-one passengers shot and killed, two British officials and two Indian soldiers dead, plus two local residents killed by gunfire. The next few weeks saw a full-scale counter-insurgency-style hunt for passengers who had escaped during the melée, including Gurdit Singh. Those who were captured were interned under wartime emergency legislation.

The release of virtually all of the prisoners late in 1915, however, did not suppress the spirit of rebellion among Sikhs in Calcutta and beyond. The nationalist press in Indian continued to honour the Komagata Maru passengers and Gurdit Singh — who remained at large until 1922, when the pacifist Mohandas K. Gandhi urged him to give himself up — “as warriors against racism” (p. 85). In Calcutta itself, what Chattopadhyay acknowledges was “a tiny segment of Sikh workers” (p. 96) joined a revolutionary underground that continued agitating against British rule for decades after the end of the First World War. The movement was especially strong among taxi drivers in the 1920s, when, in collaboration with insurgents, a number of robberies were carried out to fund the underground press and other activism.

Although her account of activism in the post-First World War years tends to descend into excessive detail lacking the firm direction of the early chapters, in the last third of the book Chattopadhyay offers evidence to confirm the long-term significance of the voyage of the Komagata Maru — both its first phase east to Canada, and then west back to India. Rather than being forgotten, the five-month affirmation of revolt “shaped future militancy and the organized postwar transmission of the ship’s memory as a symbol of resistance among the Sikh workers in the industrial centres of southwest Bengal” (p. 5). Forgotten for decades in Canada, the Komagata Maru remained a symbol of Indian nationalism and, more broadly, anti-racist activism in the country where that spark of rebellion had been kindled.

*

Larry Hannant thrills to the hunt for history in the everyday, suspects that the only route to the conquest of Berlin is over the Stolperstein Pass, subscribes to Vincent Scully’s warning that “Everything in the past is always waiting, waiting to detonate.” He’s the author of All My Politics Are Poetry (Victoria: Yalla Press, 2019 – order through yallapress.ca). His forthcoming book is an edited collection titled Bucking Conservatism: Alternative Stories of Alberta in the 1960s and 1970s (Athabasca University Press, 2020).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “#685 Tracking the Komagata Maru”

Good article. I have been studying Komagata Maru since Adiya Choudhary’s article appeared in Indian Express in May, 2016. I have also read some books from Gurudwara, Calgary. Still searching details. Keep up the good work!

Comments are closed.