#683 Nature’s advocates and activists

Advocates and activists

by Graeme Wynn, with Jennifer Bonnell

An extract from The Nature of Canada, edited by Colin M. Coates and Graeme Wynn (Vancouver: On Point Press, an imprint of UBC Press, 2019)

*

Jenny Clayton has reviewed The Nature of Canada for the Ormsby Review — see #603, Deep time to time slipping away (August 26, 2019) — but we are pleased to provide a chapter here by Graeme Wynn and Jennifer Bonnell, excerpted with kind permission of UBC Press, as a teaser. The sixteen chapters of The Nature of Canada include contributions from BC writers Colin Coates, Julie Cruikshank, and Tina Loo — Ed.

*

The most famous environmentalist of recent time is a Canadian. Surprising as this may seem in the company of Al (“Inconvenient Truth”) Gore, Gaylord (Earth Day) Nelson, James (Gaia) Lovelock, Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, English broadcaster David Attenborough, Indian activist Vandana Shiva, and others, David Suzuki’s global pre-eminence was announced in a Maclean’s cover story in November 2013. Coming just a month after an Angus Reid poll identified him as one of the country’s most admired figures, and two years after Reader’s Digest declared him its “most trusted Canadian,” this celebration of Suzuki the environmental crusader no doubt stirred the green patriot hearts of many Canadians. They had, after all, ranked Suzuki fifth (and first among those living) in a 2004 CBC Television contest to identify “The Greatest Canadian” of all time.

The most famous environmentalist of recent time is a Canadian. Surprising as this may seem in the company of Al (“Inconvenient Truth”) Gore, Gaylord (Earth Day) Nelson, James (Gaia) Lovelock, Kenyan Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai, English broadcaster David Attenborough, Indian activist Vandana Shiva, and others, David Suzuki’s global pre-eminence was announced in a Maclean’s cover story in November 2013. Coming just a month after an Angus Reid poll identified him as one of the country’s most admired figures, and two years after Reader’s Digest declared him its “most trusted Canadian,” this celebration of Suzuki the environmental crusader no doubt stirred the green patriot hearts of many Canadians. They had, after all, ranked Suzuki fifth (and first among those living) in a 2004 CBC Television contest to identify “The Greatest Canadian” of all time.

But fame is fleeting, subjective, and locally rooted (even when it claims global reach). When the Guardian published its list of “Earthshakers: The Top 100 Green Campaigners of All Time” in 2006, Suzuki ranked thirty-fifth, well behind Attenborough, Lovelock, Maathai, Gore, and Shiva and trailing Ken Livingston, the former mayor of London, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, body builder and politician. Even the Maclean’s story had its contrapuntal note. It pointed out that Suzuki himself had declared environmentalism a failure in spring 2012, and it screamed “David Suzuki Loses Faith in the Cause of His Lifetime” across its front cover. World renown Suzuki may have, the magazine seemed to be saying, but let’s not get carried away with too much enthusiasm for his cause. Suzuki, a “force of nature,” to borrow the title of a film about his life, was beset by doubts and doubters. The “green movement’s chief messenger” had come to wonder “just what he and his compatriots have really accomplished.”

Despite this sombre note, David Suzuki offers a singular perspective on the complex story of Canada’s modern green movement. In placing Suzuki at the centre of our account of this movement, we make no claim that Suzuki is a hero or a great man who made history. We are fascinated, rather, by the relationships between the individual and his setting in a society created by “the work and lives of countless human beings.” In this view, Suzuki was shaped by, and helped to identify, the concerns of his time. He clarified issues and gave voice to many of the anxieties of his contemporaries because he could see more clearly than most “where society was headed and what it needed.”

When asked to explain how he became a TV personality, Suzuki often answers, enigmatically,“Pearl Harbor.” As the child of Canadian-born parents of Japanese descent, Suzuki was moved in 1942, at the age of five and with his family, from Vancouver to an internment camp in the mountainous interior of British Columbia. Forbidden from returning to the Coast at war’s end, the family relocated to southwestern Ontario. A dozen difficult years after the first relocation, the young Suzuki won a scholarship to Amherst College in Massachusetts. Graduation took him to Chicago for a doctorate in genetics, followed by a postdoctoral appointment at Oak Ridges in Tennessee. Disaffected and radicalized by racial segregation in the American South, he returned to Canada. After a year in Edmonton, he took a faculty position at the University of British Columbia in 1963, where he threw himself into genetic research and became a rising star in the field. In the late 1960s, he spent a semester at Berkeley. Student protest was in full swing, and he embraced the counterculture.

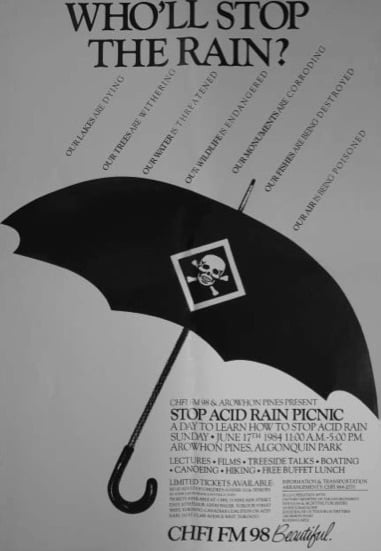

Pearl Harbor also led the United States into the Second World War, to the development of nuclear weapons, to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to the Cold War, the nuclear arms race, and the testing of hydrogen bombs on land and sea. These escalating developments spawned anxiety about the consequences of radioactive fallout, leading to the Voice of Women campaign to measure and prevent the contamination of human bodies and to the Don’t Make a Wave rallies that inspired the first Greenpeace voyage to oppose nuclear testing in Amchitka. At much the same time, Poisons, Pests, and People (a Canadian film documenting the collateral damage of chemical warfare against destructive pests), Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and a controversial 1967 CBC Television broadcast called Air of Death (recounting the grim consequences of toxic emissions from industrial plants and automobile exhausts) brought many Canadians to realize that pollution was poisoning people’s lungs and lives.

With ferment as well as pollution in the Canadian air, young people imbibed the former to organize against the latter. Pollution Probe, a major voice against society’s polluting ways, began at the University of Toronto and had its counterparts in Edmonton (Save Tomorrow, Oppose Pollution or STOP), in Montreal (Society to Oppose Pollution, also known as STOP), and in Vancouver (Society for Pollution and Environmental Control, or SPEC). Pollution Probe even had a cleverly named Toronto predecessor in GASP (Group Action to Stop Pollution). With the American civil rights movement and its dream of a better world in the background, students across the country also responded to the Paris student uprising against capitalism, consumerism, and entrenched authority in May 1968 and, two years later, to the National Guard shooting of four Kent State University students protesting against escalation of the Vietnam War. Many spoke out against the use of Canadian university facilities to produce weaponry for the US military: “We should not be a cog in a machine which is invading Vietnam,” said Professor Chandler Davis at the University of Toronto. Opposition to the war galvanized students; it was “the backdrop against which everything happened.”

Influenced by his sojourns in Tennessee and California, Suzuki was in tune with the times in his early years at UBC. Closer in appearance to the stereotypical hippie than a lab-coated scientist, he often seemed to prefer the role of “guide by the side” of undergraduates to the “sage on the stage” persona of more traditional instructors. He joined students in wide-ranging informal discussions and was often engaged in antiwar debates. Extrapolating from his genetic studies, he offered students the view that people are basically fruit flies who hatch out as maggots and defecate all over the environment. He wanted to make the point that it is the few who become really powerful (implying American political and military leaders) who are really dangerous. But for all his activism and his concerns about the links between genetics and racial stereotyping, science and the military, Suzuki found a haven in his laboratory and sanity in science.

When CBC Vancouver came calling, it was to capitalize on Suzuki’s growing reputation as someone who could talk about science in lay terms. A series of half-hour television programs, Suzuki on Science, went on air in 1971 and 1972. Envisaged as educational programs for a youthful audience, they began with genetics – discussing fertilization and genes, immune systems, and so on – but then encompassed other areas of science. In 1974, Suzuki was appointed host of CBC Television’s Science Magazine, which ran in prime time. In 1975, he also became the first host of Quirks and Quarks on CBC Radio, a show that “made science accessible and interesting to the mainstream listening audience in a unique and offbeat fashion.” Recognizing the rapidity with which science and technology had changed the world in two decades, Suzuki wanted to provide a better understanding of what it is to be human and to help listeners choose between the good and the evil that science offered. Frank, passionate, and outspoken, he was increasingly recognized as a media personality, even as many of his fellow scientists grew sceptical of his proselytizing.

In 1979, Suzuki left Quirks and Quarks, and Science Magazine was amalgamated with a longer-running science program on CBC Television that was renamed, in recognition of Suzuki’s celebrity status, The Nature of Things with David Suzuki. It was a transformative moment. Hosted by University of Toronto physicists Patterson Hume and Donald Ivey, The Nature of Things had been brought to air in 1960. Initially, it dealt with topics such as space technology, the causes of schizophrenia, and the functioning of the brain, and for its first decade it was “inextricably bound up with the scientific project of modernity.” Most of its episodes were about knowing and controlling the world through science. Nature, in this view, was “predominantly … a challenge to human ingenuity” or, as “a garden of the wonderful and the weird,” a place worthy of human curiosity. Responding to societal concerns in the late 1960s, the show ran half a dozen episodes on pollution and used “the comparatively new science of ecology” to suggest that humans might need to curb their demands on nature. For all that, The Nature of Things strongly espoused the notion of scientific and technological progress and regarded the future with optimism.

By his own account, Suzuki brought “a human-centered perspective” to the program that now carried his name, “revelling in our intellect and culture as special and unique.” But the show’s producer, Jim Murray (who had also produced Science Magazine), had been deeply influenced by the ideas of John Livingston, who was in effect the “philosophical guru” of the new program. Livingston was a self-described naturalist who had worked with the Audubon Society and with Murray at the CBC in the 1960s before joining the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University in 1970. In 1973, he published One Cosmic Instant: A Natural History of Human Arrogance in which he argued that humans in developed countries had separated themselves from the natural world that sustained them. Assuming superiority over nature, they mistakenly believed that humans had absolute power and authority over the nonhuman. By the end of the decade, Livingston was elaborating these ideas into a trenchant critique of the “perceived dichotomies that flow from the ‘mind/matter,’‘spirit/flesh’ dualism inherent in western cosmologies.” These cosmologies, he wrote in his 1981 book The Fallacy of Wildlife Conservation, place “man” in the same relationship to “non-man” as they do intellect to emotion.

To Suzuki, Livingston’s ideas on humans and the environment were “radical, running counter to the thrust of western society.” The notion that “humans as a species” are “out of balance with nature, puffed up with an unrealistic sense of importance and incorrectly convinced of our right to exploit nature in any way we choose” was difficult for this highly trained scientist to accept – accustomed as he was to insisting that the power of the human brain and the majesty of science set humankind apart from the rest of nature. Others were making somewhat similar pleas for greater moral and ethical sensibility towards nature. Among this growing international battery of intellectuals, Canadian academic William Leiss argued, in a 1972 book titled The Domination of Nature, that long-held cultural attitudes and modern science and technology were profoundly detrimental in their assertion of human mastery over nature. It was only “reluctantly, [and] over time,” Suzuki later reflected, that he came “to understand the profundity of the ‘deep ecology’ and green movements.”

By the mid-1980s, Suzuki was collaborating with Livingston and Murray on a groundbreaking, eight-part television series, A Planet for the Taking. Examining different belief systems, cultural values, and scientific advances, it traced changing human attitudes towards nature and the impact of technology on the lives of humans, wildlife, and the environment. It called for a major “perceptual shift” in humanity’s relationship with nature and the wild. Summing up the message in an interview, Suzuki said that the series was critical of “the Western attitude, which regards humans as special and somehow separate from the rest of nature.” This, he continued, rests on the conviction that “we were created in God’s image and placed on this planet to have dominion over everything. Our definition of progress is measured by the extent to which we can dominate nature … We don’t consider ourselves part of the Earth’s ecosystem or recognize that our actions have enormous impact.” The implications were plain to see: “If we continue this way, we will not only extinguish a large number of species, which we’ve already been doing successfully, but we are going to create a planet that won’t … support us.” Drawing on average an audience of 1.8 million viewers per episode, the series earned Suzuki a United Nations Environment Programme Medal and confirmed his status as Canada’s environmental talisman. It also, in some sense, cast his future. As he acknowledged, “After a series like that, we couldn’t go back to the programming we had once done. Increasingly, our programs have questioned some of the most cherished notions of progress, the necessity for growth and the overriding concern for jobs and profit.” Through the late 1980s and into the 1990s, The Nature of Things with David Suzuki presented “a very different conception of nature and its relation to science” than its predecessor programs had during the 1970s. Now,“nature” was fragile and vulnerable; it was the unfortunate and largely helpless victim of an ongoing war waged by men and machines. Technological progress had become a poisoned chalice.

With their wide reach, A Planet for the Taking and The Nature of Things helped shape Canadian attitudes towards the environment in the final quarter of the twentieth century. But they were not the only influences. Building on their Amchitka intervention, Greenpeace activists cemented their image as campaigners “standing between the natural world and the forces that seek to destroy it” with the use of Zodiacs to disrupt Russian whaling activities off the coast of California in 1975. Two years later, in 1977, Greenpeace attracted global attention to the anti-sealing movement and to its environmental activism by bringing French film star Brigitte Bardot to cuddle a baby seal on the ice off Newfoundland. Philosophically (if not tactically and practically) allied with John Livingston in their commitment to the moral consideration of nonhuman nature, Greenpeace made clever use of the media, of “mind bombs,” and of celebrity engagement to capture attention, trace a path of lasting international relevance, and provide a model for many other environmental activists.

Canadians were also given cause to think about environmental issues by some of the country’s most prolific, widely read, and much-admired authors. Margaret Atwood’s work often invites the reader to consider the vulnerability of human beings, and she sees her writing, in part, as an effort “to warn the world against” the sort of cumulative ecological destruction that “might result in the disappearance of life from the face of the earth.” Raconteur, rabble-rouser, and incurable romantic Farley Mowat began his lifelong literary campaign to raise peoples’ environmental sensitivity with Never Cry Wolf in 1963. A Whale for the Killing (1972), set in a Newfoundland outport, was ultimately a lament for modernizing society’s loss of traditional attitudes of respect for nature. Sea of Slaughter (1984) was a true jeremiad attributing the “massacre” of wildlife in the northeastern Atlantic to the hubris of modern civilization and the failure of resource-management science. Together those works won Mowat a reputation as a fierce champion of Indigenous and ecological causes and “a latter-day prophet who railed against the rapid destruction of humanity’s bonds to animals, plants and the earth itself.”

In January 1982, Suzuki presented an episode of The Nature of Things titled “Windy Bay.” It juxtaposed lush temperate rainforest with the devastation of clearcuts, the biological profusion of the archipelago then known as the Queen Charlotte Islands (now Haida Gwaii) with the consequences of logging on Lyell Island, which had begun under government licence in 1975. Opposition orchestrated by the Islands Protection Society, a coalition of Haida and newcomers dedicated to wilderness preservation, and the Council of the Haida Nation had gained little traction through the 1970s, but Suzuki’s television program brought industry’s assault on “a priceless inheritance 10,000 years in the making” to national attention and strengthened support for escalating Haida protests against the desecration of the “islands of beauty and wonder” they called “Gwaii Haanas.” When the provincial government allowed logging to continue, seventy-two people, including several Haida Elders, were arrested at a blockade on the access road. It soon became clear that there was growing national support for the campaign against logging on South Moresby Island/Gwaii Haanas. In 1988, the BC and Canadian governments designated the area a National Park Reserve with joint management by the Council of the Haida Nation.

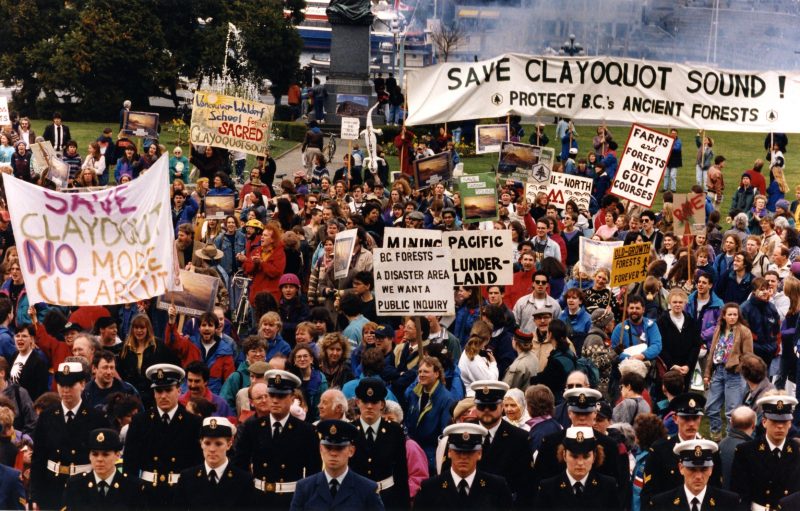

Protests against industrial logging and campaigns for the preservation of old-growth forest and wilderness in British Columbia proliferated in the 1970s and 1980s. Their roots might be traced back to the successful efforts of members of BC Spaces for Nature, who focused the “first ever citizen-led effort to save wilderness in Canada” on the Nitinat Lake area of Vancouver Island in 1971, but they all drew oxygen from events in South Moresby/Gwaii Haanas. High profile confrontations between government and industry interests, on the one hand, and Indigenous peoples and environmentalists, on the other, have come to symbolize the struggle. Think Valhalla Wilderness, Meares Island, the Stein Valley, Clayoquot Sound, the Carmanah Valley, Strathcona Park, the Purcells, the Spatsizi Plateau (Stikine), and Tatshenshini. They had their counterparts, large and small across the country, in Temagami and more recently at Grassy Narrows in Ontario, for example. Many of these campaigns were initiated, organized, and supported by environmental groups or NGOs, such as the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, now simply Wilderness Committee, which in 1991, barely a decade after its foundation, claimed thirty thousand members and revenues of $2.5 million from fees, donations, and the sale of calendars and posters bearing magnificent photographs of “the wilderness.” None of those campaigns was as (in)famous as that at Clayoquot Sound in 1993, which saw Australian rock band Midnight Oil perform at the protesters’ encampment and led to 932 arrests, making it the largest act of civil disobedience to that point in Canada.

Neither the wilderness nor the environment was far from public consciousness in the 1980s and 1990s. Some counted at least 1,800 environmental groups, large and small, across the country. Enormously varied in size and influence, and pursuing a wide range of agendas, from the defence of home places in Nova Scotia to the promotion of bicycling in Montreal, these groups were by no means unitary in organization or singular in purpose. Still, they contributed to growing environmental awareness. In 1987, nineteen in twenty Canadians were said to favour government spending on wilderness preservation. Of course, people understood wilderness in very different ways. For some, it was pristine, roadless territory; for others, simply “forest.” What is clear, however, is that both government and public recognition of the importance of “wild places” increased significantly between 1960 and 2000. At the end of the millennium, eight in every ten Canadians (the highest proportion recorded in thirty countries surveyed) claimed that environmental protection was more important than economic growth. Indeed, Environment Canada announced at century’s end that 98 percent of Canadians regarded nature as essential to human survival (it is not clear whether the other 2 percent ate or breathed). Yet policy sorely lagged behind public opinion. In 1999, Canada placed twenty-eighth among twenty-nine countries on a composite ranking of twenty-five environment indicators published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

For three decades and more, environmentalists staked their cause on confrontation – in Zodiacs on the high seas or by chaining themselves to industrial equipment, spraying dye on the coats of harp seals, or forming passive human blockades across the roads upon which loggers and miners depended. Affronted by such challenges to their legal businesses and, they insisted, to national economic prosperity, industrialists sought injunctions from a political-legal establishment that generally supported them. Early in this dance, environmentalists and Indigenous people often stood side by side, seeming to reinforce the conviction, common since the 1960s, that Indigenous people had been the continent’s first ecologists. Here and there, landscapes were “saved” from the onslaught of feller bunchers or mechanical shovels, often to be set aside as parks, and business proceeded more or less as usual in other locations.

Reflecting on his first visit to Haida Gwaii fifteen years after the “Windy Bay” shoot, David Suzuki recalled a conversation in which he had asked a Haida artist why he was opposed to logging when the forest industry brought jobs and money into local communities. Guujaaw responded that although he and his people would remain when all the forest was gone, “We won’t be Haida anymore. We’ll be just like everybody else.” Here, Suzuki realized, was a fundamentally different way of looking at the world. “To be Haida is to be intimately connected with the land, the air, the water, the fish, the trees, the birds.” What’s more, he concluded, it was “absolutely right.” This insight formed the core of his 1997 book, Sacred Balance: Rediscovering Our Place in Nature, in which he argued (as he has since) that humans “are creatures of the earth, and as such … utterly dependent on its gifts of air, water, soil, and the energy of the sun.”

Once again, Suzuki was more bellwether than clairvoyant in making this claim. Sacred Balance had many antecedents, demonstrated by its invocation of a wide range of sources ranging from the Bible and Romantic poets to modern scientists and Indigenous wisdom. The book also echoed Englishman James Lovelock’s Gaia principle in its argument that Earth itself is a living organism. And it paralleled arguments being made at about the same time by Canadian forest scientist Stan Rowe, whose late-life writings emphasized human responsibility to Earth and the importance of “seeing humanity in the perspective of the planetary worldview.” Human bodies, he wrote, were dependent on Earth for existence. People, other organisms, air, soil, and water are all contained, held together, and supported by “Earth-space.” Yet, try as he might, Rowe found it difficult to gain popular support for his ideas; “ecological sense does not come easily to … moderns and postmoderns,” he lamented early in the twenty-first century. Suzuki dressed these claims in new garb and sent them jauntily abroad to challenge prevailing views of Earth as a basket of resources for human consumption.

Easy definitions of environmental conflicts as binary encounters between the interests of frontier development and wilderness protection began to crumble as increasingly assertive Indigenous voices articulated a third understanding of the spaces at issue – they were homelands. This was not a new perspective. Justice Thomas Berger’s Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry enshrined the idea in the title of the 1977 report, Northern Frontier, Northern Homeland. But it gained cogency when the UN’s Brundtland Commission, in 1987, endorsed the right of Indigenous peoples to a decisive voice in the use of their land and through legal decisions such as that of the Supreme Court of Canada in the Delgamuukw case in 1997. Recognizing that poverty-stricken Indigenous communities had legitimate cause to use the resources of their traditional territories, some environmentalists began to back away from their insistence that not one tree should fall. At much the same time, industrialists began to see that escalating opposition in the form of consumer boycott campaigns locked them into a zero-sum game. A growing commitment to collaboration and coexistence – first in Gwaii Haanas, then in Clayoquot Sound, and then with the Great Bear Rainforest Agreement of 2006 – trumped confrontation and suggested the importance of rethinking the human/nature relationship.

These were gains – against a dark backdrop. When Suzuki announced in 2012 that environmentalism had failed, he acknowledged the movement’s many achievements, but he regretted its failure to achieve this rethinking: “Recessions, popped financial bubbles, and … a cacophony of denial” had succeeded in portraying “environmental protection … as an impediment to economic expansion.” Canada, hell-bent on expanding oil production from the Alberta tar sands, was contemplating exports of natural gas, lobbying for pipelines to carry diluted bitumen to market, and stifling the expression of opposition to its policies. It concertedly disregarded mounting evidence and anxiety that such actions were “altering the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the planet on a geological scale.”

Five years later, a new government in Ottawa committed Canada to the Paris Climate Accord and offered promise of different things to come. In 2018, it is still not clear what they will be. Juggling the creation of domestic jobs and economic development with global commitments and the planetary future (as many politicians are prone to do), the federal government brokered the implementation of carbon pricing with the provinces (particularly a reluctant Alberta) by promising new pipeline capacity to carry diluted bitumen from the Alberta tar sands to Pacific tidewater and for shipment to Asia. Then opposition to the risks of increased tanker traffic in BC coastal waters and uncertainties about future markets and prices for oil (as alternative sources of energy gain traction) led the Texas-based Kinder Morgan company to divest itself of the Trans Mountain Pipeline. The federal government stepped in to acquire and expand the existing line. But the juggling act continues, and its denouement remains uncertain – especially in light of the August 2018 Federal Court of Appeal judgment (that found flaws in the process by which the pipeline expansion was approved) and stalled development plans. Canada is off the pace needed to meet its carbon emission reduction commitments. Shifting provincial political winds are jeopardizing some earlier cap-and-trade and carbon-pricing agreements. And should the world reduce oil consumption decisively, falling markets may turn an expanded pipeline into a stranded asset. Only time, politics, and our collective commitment will tell.

*

Graeme Wynn is Professor Emeritus of Geography at UBC. As an historical geographer and environmental historian, he served that institution in various capacities including Associate Dean of Arts, twice as Head of Geography and, for six years, as editor of BC Studies. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, he served as President of the American Society for Environmental History (2017-2019) and he is Adjunct Professor (History) in the University of Canterbury, New Zealand. Wynn currently serves on the Advisory Board of The Ormsby Review and on the Advisory Board of UBC’s Green College. Much of his work has focused on Canada, although his interests extend more broadly to encompass much of the so-called British world. He edits the Nature| History| Society series published by UBC Press.

Jennifer Bonnell. A native of Duncan, B.C., Jennifer did her first two degrees at the University of Victoria and her PhD at the University of Toronto. Now at York University, she is a historian of public memory and environmental change in nineteenth and twentieth-century Canada. She is the author of Reclaiming the Don: An Environmental History of Toronto’s Don River Valley (University of Toronto Press, 2014) and the editor, with Marcel Fortin, of Historical GIS Research in Canada (University of Calgary Press, 2014). Bonnell’s articles and essays have appeared in The Canadian Historical Review, The Journal of Canadian Studies, Museum & Society, and several edited collections. She has contributed to a variety of public history projects, including documentary film and television projects for the Evergreen Brick Works and Metal Dog Films, and research and public engagement work for environment and heritage organizations in the Toronto area. Her current research explores the role of beekeepers in documenting and decrying environmental change in the agricultural regions of Ontario and New York State in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.

*

References and further reading resources

The first two paragraphs draw from Jonathon Gatehouse,“The Nature of David Suzuki,” Maclean’s, November 18, 2013; David Adam,“Earthshakers: The Top 100 Green Campaigners of All Time,” The Guardian, November 28, 2006; and Sturla Gunnarsson, dir., Force of Nature: The David Suzuki Movie (Montreal: National Film Board of Canada, 2010). The third paragraph draws from Margaret MacMillan’s discussion of Thomas Carlyle and biography in History’s People: Personalities and the Past (Toronto: Anansi, 2015), 10–11.

We focus on the recent history of environmentalism: nineteenth-century enthusiasms for natural history; the important Canadian Commission of Conservation, established in 1909; such charismatic twentieth-century figures as Grey Owl and “Wild Goose Jack” Miner; and much else fall beyond our purview. For discussions of earlier manifestations of conservationist sentiment in Canada and of Jack Miner, see Tina Loo, States of Nature: Conserving Canada’s Wildlife in the Twentieth Century (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2006); George Colpitts, Game in the Garden: A Human History of Wildlife in Western Canada to 1940 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2002); and Janet Foster, Working for Wildlife: The Beginnings of Preservation in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978). On Grey Owl, see Donald B. Smith, From the Land of the Shadows: The Making of Grey Owl (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1990), and on the Commission of Conservation, see Michel Girard, L’écologisme retrouvé: Essor et déclin de la Commission de la conservation du Canada (Ottawa: Les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1994).

For more on The Air of Death, see Ryan O’Connor, The First Green Wave: Pollution Probe and the Origins of Environmental Activism in Ontario (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2014), and for Poisons, Pests and People, see Larry Gosnell, dir. (Montreal: National Film Board of Canada, 1960). For the ferment of the 1960s, see O’Connor, First Green Wave, and on Greenpeace, see Frank Zelko, Make It a Green Peace! The Rise of Countercultural Environmentalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). Also see Roberta Lexier, “‘The Backdrop against Which Everything Happened’: English-Canadian Student Movements and Off-Campus Movements for Change,” History of Intellectual Culture 7, 1 (2007): 1–18, which quotes Chandler Davis on page 13 and Martin Loney of SFU and the Canadian Union of Students on the war as “backdrop” on page 1. Suzuki’s maggot analogy is available in Clip 3 of Gunnarsson’s Force, on the NFB website, and in the CBC clip “David Suzuki with His Students: ‘We Are All Fruit Flies,” Telescope, January 4, 1972 (which is available online and also includes the sanity in science point). For Suzuki’s perspective in the 1970s, see the television interview with Roy Bonisteel,“David Suzuki on Making Science Accessible,” Man Alive, March 8, 1977, available on- line. The accompanying gloss includes the quotation describing Quirks and Quarks. The history of The Nature of Things is traced in Glenda Wall, “Science, Nature, and ‘The Nature of Things’: An Instance of Canadian Environmental Discourse, 1960–1994,” Canadian Journal of Sociology/Cahiers canadiens de sociologie 24, 1 (1999): 53–85, which includes the “inextricably bound” (55),“human ingenuity” (59), and “wonderful and weird” (68) quotations.

The “science of ecology” quotation is from the incomplete list of The Nature of Things episodes at TVArchive.ca. John Livingston’s “perceived dichotomies” quotation is from his The Fallacy of Wildlife Conservation (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1981), 133. Suzuki’s early assessment of Livingston’s ideas is from his Metamorphosis: Stages in a Life (Toronto: Stoddart Publishing, 1987), 260. His comment about Planet is from an interview with Ron Wideman, reported in Mirza Abu Bakr Baig,“English Essays in the Wild Project,” available online.

The best place to start for Atwood’s environmental perspective is Ron Hatch, “Margaret Atwood, the Land and Ecology,” in Margaret Atwood: Works and Impact, edited by Reingard M. Nischik, 180–201 (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2000). The quote about Mowat as a “latter-day prophet” is from Maclean’s, August 12, 2002, 48–49. The “priceless inheritance” quotation is from Ian Gill, All That We Say Is Ours: Guujaaw and the Reawakening of the Haida Nation (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2009), 111. For “islands of beauty” and the protest, see David Rossiter,“The Nature of a Blockade: Environmental Politics and the Haida Action on Lyell Island, British Columbia,” in Blockades or Breakthroughs? Aboriginal Peoples Confront the Canadian State, edited by Yale D. Belanger and P. Whitney Lackenbauer (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014), 71.

For BC Spaces for Nature and the Nitinat Triangle, see the BC Spaces for Nature website. For the Western Canada Wilderness Committee, see Michael R. Mason, “The Politics of Wilderness Preservation: Environmental Activism and Natural Area Policy in British Columbia” (PhD diss., Cambridge University, 1993), 142–49. Much has been written about the Clayoquot protests and their aftermath. See, among others, Tzeporah Berman, This Crazy Time: Living Our Environmental Challenge (Toronto: Knopf Canada, 2011), and Warren Magnusson and Karena Shaw, eds., A Political Space: Reading the Global through Clayoquot Sound (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

The estimate of 1,800 environmental groups is from Jeremy Wilson, “Green Lobbies: Pressure Groups and Environmental Policy,” in Canadian Environmental Policy: Ecosystems, Politics and Process, edited by R. Boardman (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1992), 110–11. For cycling in Montreal, see Daniel Ross,“‘Vive la Vélorution!’: Le Monde à Bicyclette and the Origins of Cycling Advocacy in Montreal,” in Canadian Countercultures and the Environment, edited by Colin M. Coates, 127–50 (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2016); on Nova Scotia, see Mark Leeming, In Defence of Home Places: Environmental Activism in Nova Scotia (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2017). For Environment Canada and OECD and other survey figures, see Larry Pynn,“Environment Tops Poll of Canadians’ Concerns: The High Ranking Given Pollution and Conservation Issues is Being Attributed to an Improving Economy,” Vancouver Sun, September 20, 1999, A4; Environics International,“Public Opinion and the Environment” (opinion poll conducted for Environment Canada, 1999); and David Boyd, Canada vs the OECD: An Environmental Comparison (Victoria: Eco-Research Chair of Environmental Law and Policy, 1999) and Canada vs Sweden: An Environmental Face-Off (Victoria: Eco-Research Chair of Environmental Law and Policy, 2002). Suzuki’s conversation with Guujaaw is recounted in Gill, All That We Say, 111, and by Suzuki in Gunnarsson, Force. The “creatures of the earth” quotation is from Suzuki’s Sacred Balance: Rediscovering Our Place in Nature (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2007). James E. Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis is in his The Ages of Gaia: A Biography of Our Living Earth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988).

For J. Stan Rowe, see his Home Place: Essays on Ecology (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 2002) and Earth Alive: Essays on Ecology (Edmonton: NeWest Press, 2006). The last paragraph draws from Suzuki’s 2012 blog post “The Fundamental Failure of Environmentalism.”

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.