#677 The lurid lure of lucre

Searching for Pitt Lake Gold: Facts and Fantasy in the Legend of Slumach

by Fred Braches

Victoria: Heritage House, 2019

$9.95 / 9781772032765

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

*

Searching for Pitt Lake Gold stands in a long series of popular adventure books that celebrate gold, wilderness, and British Columbia’s adventurous colonial past. This is one of the best.

Searching for Pitt Lake Gold stands in a long series of popular adventure books that celebrate gold, wilderness, and British Columbia’s adventurous colonial past. This is one of the best.

There is certainly lots of gold to choose from: the Fraser in 1858; the Tulameen, Similkameen, Rock Creek, and Mission Creek in 1859; Williams Creek in 1862; Cherryville in 1876; Hedley in 1900; not to mention a couple of lost Spanish mines, the Lost Lytton mine, the lost Jolly Jack Mine, the Lost Edmunds Quartz Deposit, Hunter Jack’s hidden motherlode on the Bridge, and on and on and on. Plus, there’s Slumach’s Gold above Pitt Lake. It’s the best of them all: a whole creek bottom consisting of gold nuggets. That’s the one whose stories Fred Braches explores.

The literature about Pitt Lake gold would fill a small-town library. What makes Searching for Pitt Lake Gold welcome is that Braches takes the time not only to dismiss outlandish claims (written to sell newspapers and lure gold investors), but also to treat the Indigenous history of the Pitt Lake story with respect.

That’s welcome. British Columbia was densely populated before all the adventurers arrived. It has its own history. Its people have their own motivations.

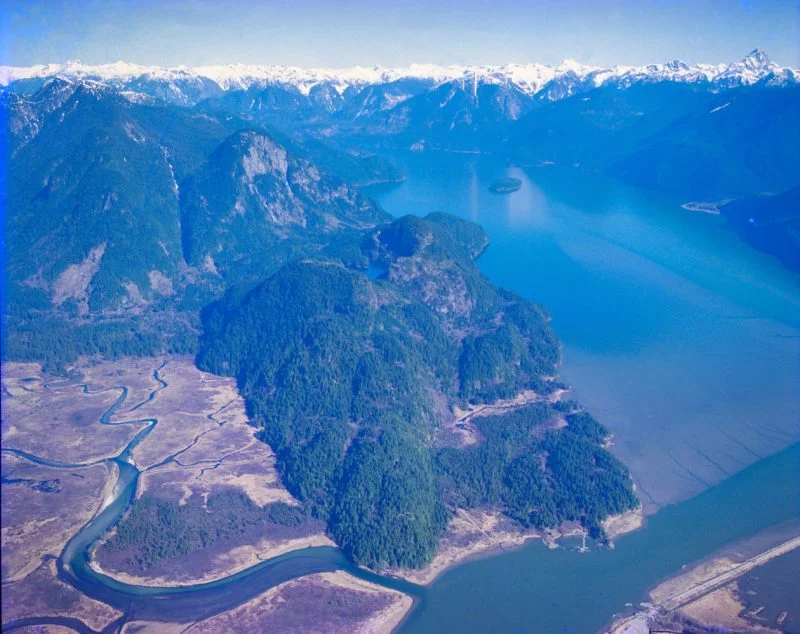

Pitt River enters the gold story in 1858, when an early map of the Fraser Mines marked the area with the legend “much gold bearing quartz rock” and “Indian mines.” How all this was known when the region was unexplored is anyone’s guess.

For years, the Katzie did a good business guiding people through the region. Braches surmises that they told romantic stories about gold to keep this business going. The book would have benefited from including his grounds for this suspicion.

There are a lot of stories to go around. Slumach enters the gold story on September 8, 1890, when he walked up to a man named Louis Bee on the Pitt River and shot him point blank. He was hanged for this crime on January 16, 1891. It wasn’t brought up at the trial that Bee and his companion Seymour (the witness to the crime) were selling illegal liquor to the Katzie Nation. Braches suggests that this was no random killing but an act of self-defence.

It could well have been. The more dramatic story stuck, however. It stuck so tight that journalist Jack Mahoney published a fictional story about it in The Province. His is the tale of Slummock, a Métis man from Red River, who prospected on the Pitt for years, discovered a rich gold deposit, and was hanged for drowning another mixed-race prospector.

The journalist C.V. Tench went one better for a Montreal paper. He wrote about Slummock, who kept leaving New Westminster with a pretty woman and kept coming back without her, but with a knapsack bulging with gold. The gig was up when the body of one of them, with a knife in her heart, was caught in a fishing net.

Soon the real Slumach and the fictional Slummock were one in the popular imagination. The search for “Slumach’s Gold” was on.

Then it gets stranger. By 1970, a story was circulating of a tree stump in which Slumach had been firing golden bullets. In 1973, Amanda Charnlie, the daughter of the man who negotiated the real Slumach’s surrender in 1890, remembered her father telling her that Slumach had found some gold, although not much, and had met some “Port Douglas Indians from the head of Harrison Lake,” who gave him a handful of golden bullets. Braches surmises that she doesn’t want to kill the gold story. That’s a guess that stresses the practical side of Indigenous life. The mythological connections with Slumach’s story are too strong for the story to be limited to such settler cultural interpretations, however insightful.

Braches does, however, give a full picture of the transformation of this story under the hands of journalists across the continent. They included transcripts of death letters and confessions about discovering the mine. All suggest secret knowledge, as if the real information were circulating underground.

Between 1945 and 1975, for instance, British Columbia newspapers published more than a hundred articles about Slumach’s lost mine. By 1950 alone, Braches notes, “the media had set the number of fatalities related to the search for the mysterious mine at twenty.” They didn’t say who they were or how they had died.

Fear was definitely part of the myth. Rumour had it that only an Indigenous miner would find the gold. Spooked by such racial fear, prospectors either found the mine (temporarily) because they were evading grizzly bears, or failed to when they were chased off by predatory cougars.

Just as bizarrely, a retired Canadian civil servant from Ottawa, George Stuart Brown, claims to have found the mythical streambed of golden nuggets near Tessarossa Lake in Garibaldi Provincial Park. As it was off-limits to mineral exploration, he took no gold out. Instead, on August 20, 1974, he wrote the Director of the Parks Branch asking for a permit to go into the park, retrieve a few surface samples, and prove the find.

“The find I estimate at a value of well over one billion dollars, probably as high as twenty,” he wrote. He was turned down.

He followed up with a letter to the Minister of Mines and Petroleum Resources. He was turned down again. His letters to Premier Bill Bennett went unanswered.

In his subsequent attempts to gain an audience, he offered popular tales of Slumach and uncorroborated reports from later prospectors as proof of the gold. Before his death in Kamloops in 1990, he had made over half a dozen trips into the park to bring out samples illegally. All failed.

The search continues, though. That the Geological Survey of Canada reports that the Pitt Lake area is relatively poor in gold, is apparently stopping no one.

Because Golden Ears Park, on the east side of Pitt Lake, and Pinecone Burke Park on its west shore, preclude prospecting along the lake itself, attention is now on the narrow corridor to the north, between the head of Pitt Lake and Garibaldi Park.

After his wonderful dissection of myths surrounding the gold of Pitt Lake, Braches ends with the very romantic story he has worked so well to dispel:

If you ask me, it can be nowhere else. After all, it was in one of those streams up north of Pitt Lake that, almost 150 years ago, a nameless Indigenous man, likely a member of the Katzie First Nation, found that “good prospect of gold” that turned out to be the fabulous placer spawning a legend of epic proportions.

Well, no. The gold doesn’t, actually, have to be there at all. That Braches says it does demonstrates that the work of British Columbian culture to fully integrate itself with Indigenous culture is hard. That a book like this can come out of the struggle shows the rewards it can bring.

Along the way, though, Braches is a solid guide through a dazzling array of tantalizing myths and mysterious and apocryphal tales of curses, lost letters, eyewitness reports, and journalistic pot-boiling. He is very good at according Indigenous people respect. He paves the wave for the bigger story of how Indigenous storytelling works, and how it brings in mythical material of its own with roots in such things as trickster, medicine man, and Sasquatch tales, and quite different truths. They don’t appear to include placer mining.

This reworking of the gold tale genre in Searching for Pitt River Gold is welcome. It is a readable and companionable book which shows that the whole B.C. historical adventure genre can gain strength and legitimacy by being rewritten to include Indigenous material and motivations.

It also shows how much farther there is to go.

*

Harold Rhenisch was raised in the grasslands of the Similkameen Valley and has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are the Cariboo meditation Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and the Similkameen orchard memoir, Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on his Cariboo-Chilcotin books published by Country Lights: Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as The Bowron Lakes (2006), and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan: One Country without Borders, from his home in Vernon. For seven years, he has toured the grasslands of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho while working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region set in its American context, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon. Harold Rhenisch lives in Vernon.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#677 The lurid lure of lucre”