#674 Emily Carr in France

Emily Carr. Fresh Seeing: French Modernism and the West Coast

by Kiriko Watanabe, Kathryn Bridge, Robin Laurence, and Michael Polay

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2019, in collaboration with the Audain Art Museum

$40.00 / 9781773270913

Reviewed by Robert Amos

*

Many people have a prejudice about Emily Carr. Crazy lady with a monkey, they say, and her paintings are too dark — that deep green woodsiness, and those spooky totems. Their minds are made up, and won’t be changed.

Many people have a prejudice about Emily Carr. Crazy lady with a monkey, they say, and her paintings are too dark — that deep green woodsiness, and those spooky totems. Their minds are made up, and won’t be changed.

Too bad. Because Emily Carr, who I describe as Canada’s most important artist, was a woman of courageous creativity, whose evolution never ceased throughout her long career. After growing up in Victoria, Carr (1871-1945) first studied in San Francisco and became a good “provincial” adherent of the traditional manner. Then she spent five years in England and became adept at the English watercolour style. Ten years later she spent a year in France, keying up her colours and returning as the most modern painter in Canada. Sadly, that fact was lost on her friends and neighbours.

Then, in 1927, Carr was discovered by the National Gallery. Inspired by Lawren Harris of the Group of Seven, she subsequently developed a streamlined expressionism. After Harris’s departure from Canada in 1933, she left this influence behind and created her own unique calligraphic manner of painting, depicting not only the forest interior but also the vast sea and sky, using diluted oil paint on rough paper.

Carr’s artistic periods have been studied with great perception by dedicated scholars — Doris Shadbolt looked at the dark forests; Kathryn Bridge discovered and published Carr’s “funny books,” illustrating her early trips to Alaska and England; Gerta Moray wrote a monumental study of Carr’s visits to First Nations villages. With Fresh Seeing, a new book from the Audain Museum and Figure 1, her time in France in 1910 and 1911 — a pivotal moment in the artist’s life — is brought to light.

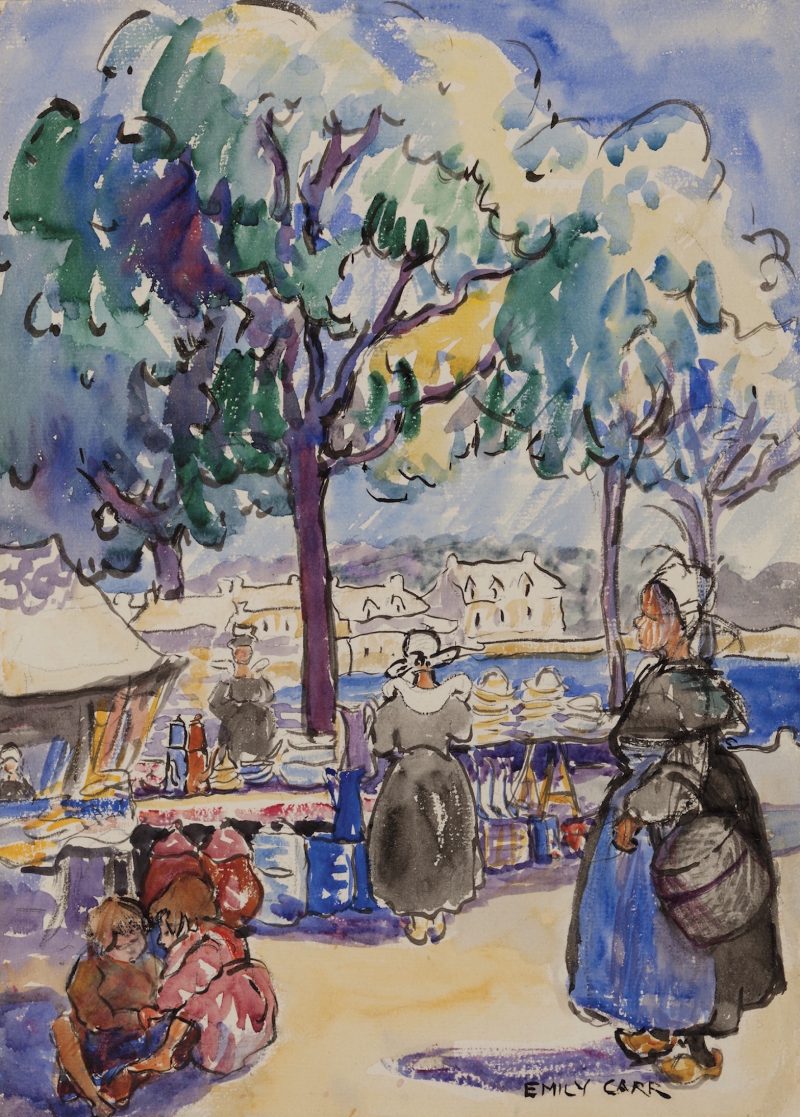

In 1910, as she approached the age of 40, Carr knew that her English watercolour manner was not up to the challenge of representing the lands and people of the North Pacific coast. Just before this, in about 1906, Picasso had shone a light on the tribal arts of Africa, and Henri Matisse violently intensified his colour palette and gave birth to Fauvism. Carr decided to go to Paris and find teachers who could take her art to that new level. She found Henry Phelan Gibbs, an advanced English painter, who was teaching the new way of colour at St. Efflam in Britanny. And then she went to work on the coast at Concarneau with Frances Hodgkins, a young woman from New Zealand who became an inspiration to her.

This new book, Fresh Seeing, includes a number of essays, but its core is research by Dr. Kathryn Bridge. Bridge recently retired after about 40 years at the Provincial Archives of British Columbia (now part of the Royal B.C. Museum) where she took a proprietary interest in the Carr collection through many years. The Museum holds the largest collection of Carr’s work, particularly rich in sketchbooks, field studies, and early works in many styles. The Museum also holds Carr’s manuscripts, library, and photo albums, which are crucial to the ongoing study of this wonderful artist.

In recent years Bridge has literally followed in the artist’s footsteps in the French villages and countryside she painted, and also on the B.C. coast. Now, with the benefit of on-line research tools, she has been able to clarify the details of Carr’s experiences. The artist herself wrote about most chapters of her life, but often fudged the details in the interest of a good story. Now Bridge blows away the mist and reveals the fascinating truth of what really happened.

The paintings presented in the book are on exhibit at the Audain Museum in Whistler (and will later be shown at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in Fredericton, New Brunswick). Note that the Audain Museum is one of the best reasons to make the trip to Whistler. It is architecturally striking and houses an extensive display of Carr’s paintings. In fact, the Audain’s holdings of Carr’s French period artworks inspired this exhibit.

Kiriko Watanabe, curator at the Audain, wrote an essay for the book elucidating how Carr’s painting changed when she returned from France to the coast and took the first of her legendary trips to the “totem forests.” Watanabe also considers how Carr’s artistry is perceived today in native communities. “While some may consider Carr’s work to be cultural appropriation,” Watanabe explains, “others may see in her representation of First Nations cultures, a great passion for art, as well as a deep appreciation for the long and rich history of First Nations Peoples.”

Watanabe has included two modern pieces by Sonny Assu. On top of Carr’s painting of his hometown, Cape Mudge on Quadra Island, he has overlaid a descending “Amerind” space ship, ready to beam up an Indian family sitting in the foreground and take them up and away. Watanabe’s curatorial intention is good, but in this book seems rather beside the point.

The final essay, by Vancouver commentator Robin Laurence, introduces a speech Carr made at Victoria’s Crystal Garden ballroom in 1930 under the title “Fresh Seeing.” “I hate like poison to talk,” Carr began her lecture, but she went on to say things that continue to be relevant and inspiring today. In her essay Laurence traces the roots of Carr’s philosophy and provides useful context for the speech. The book concludes with the speech presented in full, transcribed from the artist’s original manuscript. It’s an effective and appropriate way to conclude a useful and attractive book.

*

Robert Amos was the art writer for the Victoria Times Colonist newspaper for 32 years. His most recent books are the best-selling E.J. Hughes Paints Vancouver Island (Victoria: TouchWood Editions, 2018) and E.J. Hughes Paints British Columbia (Touchwood, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.