#665 Poems of grief and acceptance

Salt and Ashes

by Adrienne Drobnies

Winnipeg: Signature Editions, 2019

$17.95 / 9781773240480

Reviewed by John Swanson

*

Adrienne Drobnies’ Salt and Ashes is a powerful, intimate book, a journey marked by a legacy of early pain and power inflicted — the old suffering, then the new; the loss of a beloved husband, the grief, emptiness, acceptance, and recovery, the poet arriving at a new understanding of love.

Adrienne Drobnies’ Salt and Ashes is a powerful, intimate book, a journey marked by a legacy of early pain and power inflicted — the old suffering, then the new; the loss of a beloved husband, the grief, emptiness, acceptance, and recovery, the poet arriving at a new understanding of love.

I’ll talk about the book in its three sections, as they develop the arc of this work.

Section I

The first section gives insights into early years, and the rules for survival learned there. From the first poem, “Witch Hazel Song” (p. 13):

Teach me the rules

you learned as a child and how a switch cut

from witch hazel is a lesson in pain and power.

Early on in the book, in “It’s a blue day” (p. 14), the poet hints that there is another way of being:

“I wonder/ where was I/ and how old/ when Joanne Kyger/ born the same year/ as my mother/ sailed between San Francisco/ and Japan/ I — a small child — / beaten, shredding curtains/ with a vengeance” (p. 14).

Joanne Kyger, an early Beat Poet and one of the first woman Beats, becomes a different model of what a girl might become, and informs the journey in the second and third sections.

And then “The Sacred Yew” introduces us to the Taxus tree that “yields a poison drug/ … for the canker that moans in the flesh” (p. 15) and forewarns us to a different kind of suffering to be encountered later in the book. This is subtly resonant, as it hints at the canker of early beatings to the flesh, and the shadow of cancer to come later in the story.

The language in the book is a challenging mix of the sensual (from “Ring Dance” (p. 16) “… ceiling plaster sprinkled our hair/ like crumbly feta, garnish to the salt stink/ of pleasure”); and, in the Third section, scientific language and concepts which sometimes illuminate, and for non-scientists sometimes mystify. For example, from “Singularity” in the Third section: “a phase transition is a singularity in the complex plane/ water to ice/ helix to coil;” and “the shallow eutectic of energy” (p. 71).

This first section contains a number of poems of dreams, forebodings about death, the fragility of new life. From “Stanford Hospital, 1987” (p.18):

I have given birth to this breath,

this child, this life

this death.

And from “Perhaps if my own life had been cleaner” (p. 20), a poem from the imagination:

I pushed her in front of the car – her death was quick

….

One morning my mother told my brother and me

to stay in bed until she came back,

She didn’t return for three days.

…..

When I asked her she said “visiting.”

The sense of foreboding, of unsafety, increases. In “Home before dark” (p. 36), a jogger grabs her around the neck, she screams and is released, and is “home late/ with a head full of rage/ but I don’t phone the police.”

Then the foreboding enters the heart of the book. In “The Last Days” (p. 33) we crash into the real truth of the poems. I quote the whole poem as it is a central cry of the book:

I lie on the floor and

listen to the gapped breath –

read aloud from “The Little Prince”

feed you spoonfuls of

vichyssoise and watermelon

nibble at the remaining bites (such tender details)

I wear a black silk blouse and

the long flowered skirt

you gave me from Nepenthe (inducing forgetfulness of pain)

and caress myself

with your knowledge and love

your hands now absent from me (again, such tender details)

I kneel with three other women

as the space between breaths lengthens

Alone once more

with the stars and soft night

a breeze brushes by

startles me

The day grows light

with the blue of summer

I wash and oil your body

to know one last time every centimetre,

every dimension, every crevice

touch the cold of your forehead

all your knowing still there

Because anger and bitterness are gone

I can write now of the last days

and not be mad with grief.

Note the line, “and not be mad with grief.” Here is a map for the rest of the book.

The first section ends with a wisp of a poem — “Vancouver” (p. 43) — and yet, such breath-stopped wrenching from our usual assumption that death will come at the right time, later, in old age.

Landing

I thought

this is the place

I will die

But not you

I did not think you.

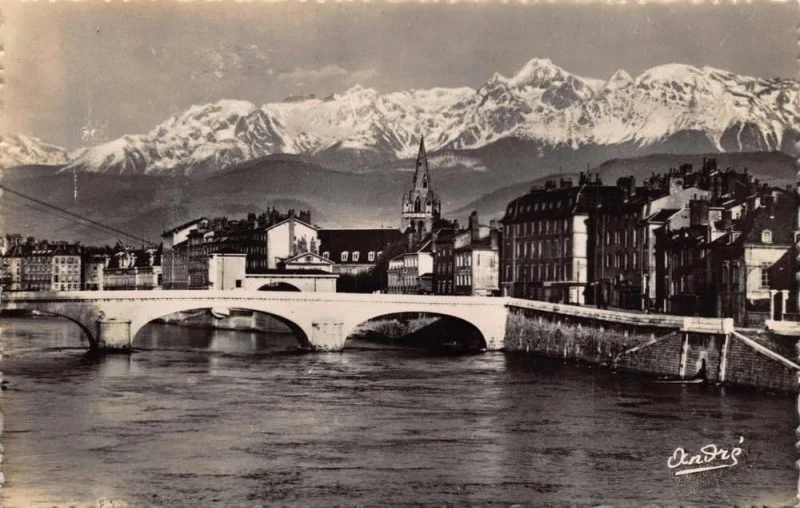

Section II – Randonnées

The middle section, “Randonnées,” is a suite of poems about a time spent living in Grenoble, France. Although the poet is living with her husband and daughter in Grenoble, a town both familiar and far away from her life in Canada, she spends time alone, alternately immersed in mountain hiking (“sur la montagne”) and wistful loneliness and not belonging (“dans le quartier”), wandering in the town. This sequence of poems sets her free to wander, to get in touch with herself. Randonnées are long walks or rambles. To be in the world, to forget, to sweat, to allow the moments, not chosen, to impact, leave a new memory. And the memory of this time becomes a preparation for living alone, without her beloved.

From “III Sur la montagne” (p. 49): “Sweat, sweat, sweat up the mountain.”

From “IV. Dans le quartier” (p. 50):

The woman’s dress flaps and curls under the bike

she steers around a curved ramp.

I am reminded of one woman’s desire to be beaten.

Is it the poet’s desire? Someone else’s? The desire to feel, to surrender in this awful emptiness? To paraphrase Baudelaire in “Crowds”: “The poet enjoys the incomparable privilege of being able to be (herself) or someone else, as (she) chooses. … For (her) alone everything is vacant.”

From “VI. Sur la montagne et dans le quartier – August” (p. 52):

A hard-honed knowing

tautens in thigh

muscles.

Hands tear at flowers

teeth bite the dust.

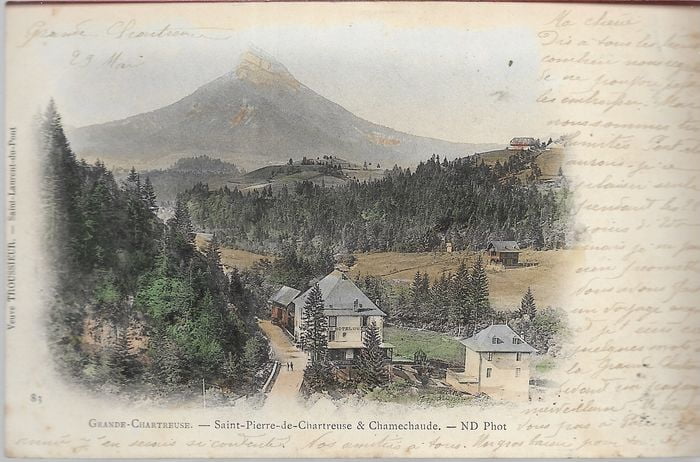

From “IX. Sur la montagne – Chamechaude” (pp. 55-56). Chamechaude, the highest peak in the Chartreuse Massif:

Have pushed harder

unremitting

since I am alone.

…

The coming and the going –

in a simple word — free.

From XI. September (p. 58):

There is red along the wall, thinning.

Happiness spouts in the midst of children

In my response is all the possibility of joy.

There is an evolving sense of emotions, and a being-in-the-place, that grounds, comforts.

From “XVII. Dan le quartier” (p. 64):

To one side the alpine glow

in the evening sky.

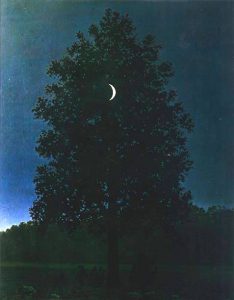

A Magritte moon hung above it.

The Belladonne chain and its fresh snows.

To the other, street and traffic.

A cyclist pedals by.

A flood of students spews forth.

…

I think, aggressively:

“This is my street, my sky

my home, and

walk on at random.”

Here the poet is talking like a photographer, seeing detail, swimming in the moment, and, finally, feeling at home, almost strutting through the street.

Section III.

We are hit right away with an abrupt change of language and state in Section III. The Section opens with “Singularity” (p. 71). A singularity, in scientific terms, is a point at which instantaneous change takes place, for example when a solid turns into a liquid, or a liquid into a gas.

The poet says “I wandered into that abstract realm that held/ and would not release me.” and “A phase transition is a singularity in the complex plane.” What are we to make of this? Why use a word we as lay people only dimly understand? Considering this, I realized that scientific language conveys the world to us at a level of detail and with a richness we cannot express in other ways. “Singularity” has many nuances, which create a richness of multiple resonances in this apparently “singular” use of the word. Mathematical singularity is a point at which a given mathematical object is not defined or not “well-behaved.” In complex analysis, Essential singularity is a singularity near which a function exhibits extreme behaviour. Technological singularity is a hypothetical time in the future when technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unfathomable changes to human civilization.

The poet says “I wandered into that abstract realm that held/ and would not release me.” and “A phase transition is a singularity in the complex plane.” What are we to make of this? Why use a word we as lay people only dimly understand? Considering this, I realized that scientific language conveys the world to us at a level of detail and with a richness we cannot express in other ways. “Singularity” has many nuances, which create a richness of multiple resonances in this apparently “singular” use of the word. Mathematical singularity is a point at which a given mathematical object is not defined or not “well-behaved.” In complex analysis, Essential singularity is a singularity near which a function exhibits extreme behaviour. Technological singularity is a hypothetical time in the future when technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unfathomable changes to human civilization.

All this leads us to:

a spring running under thin ice

a collapse of order or an initiation

a woman rising to compose herself

over a cup of coffee when the night before

she let fall each block of her body

…

thoughts do not follow a

mathematical order

they climb their imaginary axis and take root

illegally

joke with meaning

….

So recently I stopped asking

why you are

not here any more

In Grenoble and in the mountains the poet spent time alone, but in Section III begins the wrestling with the here and now of missing the beloved.

In “Man on the moon” (p. 72) the poet says:

Stolen silver brilliance again

in your departure gone

shunting moonlight through a vein

day eating up night

beside me on the pillowed now.

The waking next to the empty side of the bed, not having slept, not caring whether to get up, or not.

In “Maladaptive decadence” (p. 73), the many dreams — “high heels when running from a bear/… / a bomb in the backpack monster trucks” (no line break, a jumble in the mind); and then “grief and denial large abstract ideas/ a headfirst dive into the truth.”

More scientific concepts in “Maxwell’s Demon” (p. 74) for us to understand, but again evocative language that expresses the journey back: “light cast in/ partial differentials.” Partial differentials measure how fast a function changes when one of several variables is changed. We ask ourselves “what will change, and how will it affect the poet’s healing, her return?”

And in the title poem “Salt and Ashes” (p. 77), the poet reminds us of the loneliness that lingers:

Fine sea salt sifts through my hands with the feel of ashes

Fine sea salt sifts through my hands with the feel of ashes

in a cloisonné vase on my desk — cold metal waiting to be kissed

when loneliness delivers peppery and smashed garlic sorrows.

And yet in the same poem we have these delicious lines:

On a white cloth, I cut open cherry tomatoes, drizzle the most virgin olive oil,

rest beside them slices of crusty, yeast-aerated bread, while I alternately roast

and cool my hide in the summer sun and water outside a hotel

lost on the Finger Lakes near Aurora.

The lost husband lingers. In “Dream Wedding” (pp. 80-82),

In front of the chuppah

another man

with a witty remark

for the crowd

We swing dance

to “Ain’t she sweet”

I look again

my dead husband

“Aubade” (p. 83) is a type of poem, often a song, evoking daybreak, and also lovers separating at dawn. It echoes an earlier poem:

Impossible not to think of the first dawn without you

and the reluctance of your leaving

…

The height of the bed was higher than anything

I had ever climbed before I heaved my body across yours

How could it be you were there and not there?

And the beautiful, lyrical, joyous, questioning “Today I can write the happiest song” (p. 84), another key poem of the book, the examination of what love was and is: does she love him still? Did she always?

Today I can write the happiest song

I loved him and he loved me always.

…

and know I have him no more, know he is gone.

The poet wrestles with the questions about love, then and now: “I love him, but, uncertain, ask, how did I love him?/ … / Maybe I no longer love him.” But it is so clear she does love him.

And eventually, in “Final Blessing” (p. 93) she arrives at “I walked out one evening in the moonlight/ a woman unafraid.”

Every poem in Section III merits appreciative comments: the grandfather walking out of Poland 80 years ago, memories of the desperate teenager begging to be rescued from her life situation, the days of hell working in the lab to develop a chemotherapy that will kill the uncontrolled (“anti-apoptotic”) growth of cancer cells; but I will end with a quote from “Hymn to Life” (pp. 89-90):

After a time

you start to expect it –

this thing life hits you

with a ton of bricks,

makes you think

so this is it

again.

Persuade you

in its coy way

there’s one more card up its sleeve,

one more spot for you

on its dance card,

and it is worth living

after all.

Life slowly returns, joy is possible, another relationship might be possible. Salt and Ashes is a wonderful, heartfelt book. You can feel the grief, you can feel the struggle to return and you can feel the return with a wisdom not possible without the journey.

*

John Swanson’s book of poems and street photographs, an almost hand, beckoning, was published by Blurb Books, San Francisco, in September of 2019. It was reviewed by P.W. Bridgman in the Ormsby Review 586 (July 30, 2019).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.