#661 No direction home

Nothing to Write Home About: British Family Correspondence and the Settler Colonial Everyday in British Columbia

by Laura Ishiguro

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019

$34.95 / 9780774838443

Reviewed by Robert Hogg

*

In Nothing to Write Home About, Laura Ishiguro presents us with an opportunity to enlarge our ideas of nineteenth century colonial life, inviting us to reflect on the private side of colonisation as well as the public. In pursing this project Ishiguro took on a difficult task. As Laura Kroetsch remarks, “Letters and diaries are often confusing, occasionally quite boring and rarely do they include vital information like who Sally and Grace actually were.” Letter writers conceal as much as they reveal, and Ishiguro has undertaken a forensic reading of her material, examining the unspoken as well as the spoken to explain how British family correspondence facilitated and reflected the normalisation of settler colonial life and order. Simultaneously, settler correspondence obscured the presence of Indigenous people. For most correspondents most of the time British Columbia was terra nullius, a condition which gave settlers carte blanche to establish firstly an outpost of empire, and ultimately a British polity.

In Nothing to Write Home About, Laura Ishiguro presents us with an opportunity to enlarge our ideas of nineteenth century colonial life, inviting us to reflect on the private side of colonisation as well as the public. In pursing this project Ishiguro took on a difficult task. As Laura Kroetsch remarks, “Letters and diaries are often confusing, occasionally quite boring and rarely do they include vital information like who Sally and Grace actually were.” Letter writers conceal as much as they reveal, and Ishiguro has undertaken a forensic reading of her material, examining the unspoken as well as the spoken to explain how British family correspondence facilitated and reflected the normalisation of settler colonial life and order. Simultaneously, settler correspondence obscured the presence of Indigenous people. For most correspondents most of the time British Columbia was terra nullius, a condition which gave settlers carte blanche to establish firstly an outpost of empire, and ultimately a British polity.

Ishiguro notes that most of the literature on colonial British Columbia takes as its primary focus race and settler-Indigenous relations, considering the connections and relationships between race, gender, sexuality and space, and examining the policies, laws and practices which facilitated the dispossession of Indigenous people and the creation of a white British society. However, the fields scholars have examined aren’t necessarily those which occupied the minds and filled the correspondence of settlers. Settlers were concerned with more mundane matters: food, geography, the weather, employment prospects and gossip about each other. In writing about these mundane concerns settlers and their metropolitan readers attempted to overcome the “tyranny of distance” and maintain familial and other relationships. In this respect Nothing to Write Home About joins Emma Rothchild’s The Inner Life of Empires and Margot Fry’s Tom’s Letters as studies which examine the personal to not only illuminate private lives, but also to demonstrate how the personal and private are imbricated with the public and the political. Like The Inner Life of Empires, Nothing to Write Home About is both a microhistory and a macrohistory. It is a history of individuals and the minutiae of their lives, but it is spatially large and embraces the political, economic and ideological concerns of the mid- to late nineteenth century.

Ishiguro makes two claims about how letters worked in this fashion. Firstly, she argues that letters were the medium through which family relationships between British settlers and those who remained in Britain were maintained. Secondly, she argues that letters were a key instrument for the circulation of knowledge about British Columbia to people who would otherwise be ignorant of that small piece of Britain’s realm. Letters were used to both steer through the personal separations that were a defining feature of migration and settlement and were a part of the settler colonial project of dispossession, marginalisation, and elimination.

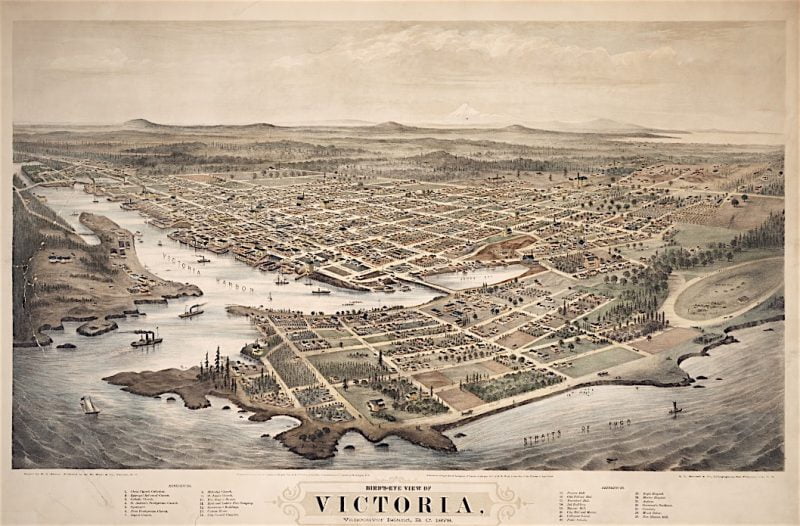

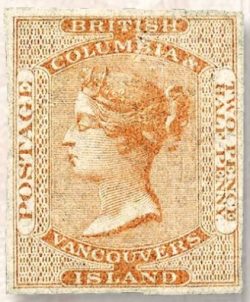

In the early twenty-first century, it’s easy to forget how central the postal system was to interpersonal communication in the nineteenth century. Ishiguro argues that the postal system strengthened and consolidated the political, economic and social linkages which made the British Empire. It bound British Columbia to the rest of the world and enabled the creation of settler British Columbia. Most importantly, the postal system and family letters together influenced decisions to migrate and settle in British Columbia and were therefore foundational to the creation of the settler colony.

While of course letters varied according to individual writers, Ishiguro identifies a consistency of materials, structure, language and content — a set of conventions mostly adhered to by correspondents and typical of wider British culture. Letter writers were engaged with a multitude of subjects. Fundamentally they were concerned with maintaining relationships and explaining their experiences in British Columbia. Correspondents expressed their feelings about each other, argued, reconciled, arranged finances, wills, businesses and marriages. They detailed the significant and insignificant, and responded to queries about British Columbia. What was deemed significant or otherwise could depend on whether one was a settler sending a letter or a metropolitan recipient. The title ‘Nothing to Write Home About’ alludes to the banality that settler life assumed after an extended period in the colony. What was once exotic — the landscape, the Indigenous people, the style of accommodation, the work — after a period could become dull and uninteresting to colonists, but often remained fascinating to those remaining in Britain.

Of particular prevalence were discussions about food. In the face of persistent urging for information about settler life, colonial letter writers turned towards descriptions of food to achieve an acceptable quota of words. Sometimes settlers related tales of cooking ingenuity, but equally fell back on grocery lists and reports of recent meals. Ishiguro reads such letters as illustrating the changing meanings of labour, markets, environment, gender class and respectability. Greater labour was often involved in procuring food and men often found themselves performing cooking duties, a role that they probably would not have undertaken in the metropole.

Death and inheritance were often delicate subjects in inter-imperial correspondence. Ishiguro investigates the epistolary conventions and ideas about death in letters of notification and condolence. Such letters characterised death in terms of acceptance, patience and Christian faith. George Kidner’s words to his daughter notifying her of her mother’s death are characteristic: “My dear Edith, it is in great sorrow of heart I am obliged to write to let you know dear Mama has fell asleep at ¼ to twelve last night.” Thomas Fawcett’s letter to his sisters-in-law notifying them of his wife’s death features the Christian language that typified many such missives: “All is over! Earth exchanged for Heaven — Suffering for Joy — The Cross, for The Crown.” Condolence letters also followed specific epistolary conventions. John Trutch wrote to his brother on the occasion of the death of the latter’s wife: “I pray God to strengthen & support you in this great affliction which He has cast upon you, & strength will come from Him.” Inheritance could be contentious, and Ishiguro argues that letters were an indispensable tool for separated relatives who sought to advance their own interests, negotiate disagreements and assert their understanding of family.

As noted above, letters could both reveal and conceal, and what was unknown was as important as what was known. Ishiguro presents the case study of Michael Phillipps, his Indigenous wife Rowena David and the letters of W. Henry Barnaby and Frederick Norbury to illustrate that secrecy, ignorance, gossip and the management of information reveals ideas about race, gender, settler colonialism and correspondence. The Phillipps/ David marriage (which was unknown to Phillipps’ family in England), was a recurring subject in the family correspondence of Norbury who, in numerous letters spanning several decades, simultaneously titillated and doused his family’s curiosity after it had been aroused by Barnaby, who had written to Norbury’s father about the Phillipps/ David marriage, after hearing about it from another party. Why anyone in Britain would need or want to know about the marriage of two people unknown to them and living thousands of miles away is anybody’s guess. Yet Barnaby and the Norburys felt the relationship was worthy of sustained gossip and speculation. Phillipps’ own silence about his marriage fuelled conjecture and hypothesis that was maintained until his death in 1916. Ishiguro believes that “epistolary families” were sustained by silence and “the strategic limits of intimacy,” and that the way gossip was managed reveals differences in colonial and metropolitan lives, values, and expectations.

Laura Ishiguro has written a fine book. Her meticulous examination of colonial correspondence is engaging and illuminating. She displays a considerable sensitivity for the language used by white settlers to discursively claim British Columbia and normalise their presence there. Ishiguro is especially skilful in summarising her conclusions at the end of each chapter, fluently articulating the tangled voices of British settlers.

*

Dr. Robert Hogg has taught history at a number of Australian universities, primarily at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). He is currently researching Australian and Canadian soldiers on the Western Front.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.