#660 For the love of the North Pacific

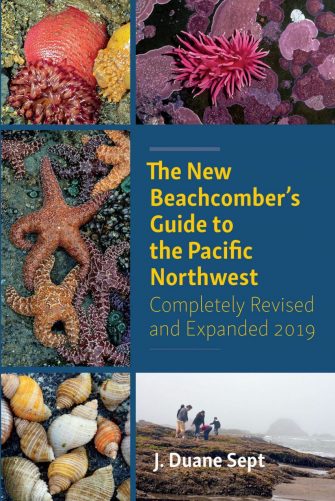

The New Beachcomber’s Guide to the Pacific Northwest

by J. Duane Sept

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2019

$32.95 / 9781550178371

(first published in 1999 by Harbour as The Beachcomber’s Guide to Seashore Life in the Pacific Northwest; reprinted 2002; second edition 2009; third edition 2019)

*

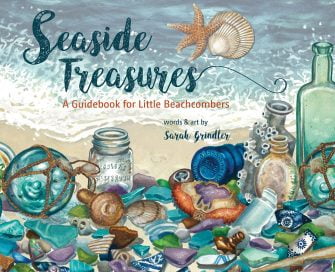

Seaside Treasures: A Guidebook for Little Beachcombers

by Sarah Grindler

Halifax: Nimbus Publishing, 2019

$15.95 / 9781771087469

Both books reviewed by Theo Dombrowski

*

Few words are more evocative for beach lovers than “beachcomber.” Putting aside associations with a seventies and eighties comedy set in Gibsons, the word stirs up scattered romantic associations, amongst them images of free-spirited wandering by the sea in quest of sea-tossed treasures. Two books by B.C. authors take full advantage of such associations in titling their books. Yet the two, J. Duane Sept’s The New Beachcomber’s Guide to the Pacific Northwest, and Sarah Grindlers’ Seaside Treasures: A Guidebook for Little Beachcombers are very different books with very different notions of beachcombing. Readers looking for books to match their own notions of beachcombing will find plenty to appeal to them in either book.

One is, first off, a book for adults, one for children, but that is only the beginning of more far-reaching differences. In fact, it is entirely possible to imagine Sept’s book being rewritten for children, and Grindler’s for adults. For Sept, the beachcomber is an amateur naturalist with a keen interest in identifying and learning a little about the rich animal and plant life along the shores of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and northern California. For Grindler, the beachcomber does have a little interest in identifying the shells and pieces of sea critters, but essentially is happy to discover any curious object along the shore — sea glass (there is a lot of emphasis on sea glass), pottery shards, garbage, and historic artifacts.

Fascinatingly, too, the two books depend on entirely different notions of classification. In this regard, Sept’s hugely substantial book is very much the conventional field guide, directed entirely to grouping, subgrouping, identifying and naming. Seadrift, even biological seadrift, such as the skate egg cases common to beaches of the open coast, has no place in a book concerned with denizens of the intertidal zone. Using colour-coded page groupings common to field guides, the book is organized into primary sections such as Sponges, Marine Worms, and Molluscs. Within those primary subsections, though, Sept opts for convenience rather than strict uniformity, so that, for example the Marine Worms are next grouped into a series of phyla, while the Molluscs, a single phyla, are divided into a series of classes (with one subclass.) For Grindler, in contrast, the key principle of grouping is, as the title suggests, “Treasures.” The very minimal text is directed less towards classifying than instilling a sense of wonder and enchantment with diversity. It is only at the end she writes to the beachcombing child: “Now that you know about sea glass, chinaware, shells, and garbage, let’s go back and look again at all the pictures in this book. Can you tell which is which?”

The two different approaches to illustrations — each striking in its own way — correspond closely to the different notions of beachcombing. Sept’s illustrations begin with a series of business-like photo-grids of common shells, coded by adjacent letters of the alphabet to names at the bottom of the page. Limpets and urchins get three views, bivalves (like clams) and univalves (snails) get only one. The rest of the book is dominated by colourful photographs, generally one per species, largely framed to show the natural environment as well as the specimen. While it is true that many molluscs are carefully arranged against a purely functional flat background of sand, often with front and back views, most of the others are photographed in situ, showing the specimens exactly as they might appear to a beachcomber. Some of the photos of molluscs show the living animal; others just the shell, sometimes one side of a bivalve, sometimes both sides. Some are accompanied by photos of eggs. Curiously, though, while nudibranchs are photographed through water, some anemones (incredibly beautiful when seen through water) are photographed for this book, high and dry, drooping ignominiously, their otherwise flower-like tentacles retracted and invisible).

The illustrations in the children’s book are paintings rather than photographs, as befits the audience. Apparently acrylic, they are carefully detailed, aiming to capture not just every whorl or facet, but also glints of light and sheens of opalescence. Unusually, though, instead of grouping the “treasures,” or placing them in a beachy setting, Grindler has made each shell, broken carapace, shard of pottery, or bit or garbage fairly small and dotted them over a white background: most pages sprinkle roughly 25 to 40 small images across two pages. The effect is a little odd, but appeals to the notion of a beachcomber as a hunter of little scattered treasures.

Unsurprisingly, Sept’s field guide includes many more different species than Grindler’s children’s book. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a more comprehensive compendium than Sept’s. The book contains over 800 photographs. A word of caution is appropriate, though. All field guides can raise false hopes, whether of birds, flowers and plants — or shore life. Just as lovers of birds will usually be disappointed with how few of the dozens of species shown in their field guide they can spot, even after years of hunting, so those who head off along a shore with this richly detailed book in their hands will soon find that they can find only a small number of the species in the book. First off, neo-“beachcombers” probably won’t realize as they head out to the shore that they would have to dig to find live specimens of many, especially bivalves and worms — no mean feat when it comes to deeply buried creatures like razor clams, geoducks, and horse clams (gapers). The unlikelihood of spotting specimens is particularly strong for those species identified as “low intertidal.” Donning a mask and snorkel, or making a point of peering into the still waters below docks (suggested by Sept in his introduction) will enormously increase the numbers of possibilities — especially of sea stars, jellies, anemones and nudibranchs.

Sea stars and jellies? Whatever happened to starfish and jellyfish? Some readers may be a bit puzzled — until they realize that Sept adopts the current convention of renaming starfish and jellyfish on the grounds that the new terms are accurate (which, deliciously, they’re not!) To add to the confusion, some readers might notice in their wanders through bookshops that some current biologists, like Lisa-ann Gershwin, can write a whole, scientifically detailed book, about “jellyfish.”

Perhaps one of the slight ironies about the two books is that, when it comes to the range of living species they include, the vast majority of beachcombers (even adults) in the Salish Sea area will find that Grindler’s book more closely matches what they see than Sept’s. Salish Sea is the operative term: Grindler has many illustrations of the same things — especially mussels and littleneck clams – and has virtually nothing from outside this area, little, for example, from the outer coasts of Vancouver Island (or Washington and Oregon). Hilariously, one tropical shell — the snakehead cowrie — peeps out mischievously from one of her pages.

When considering non-organic “treasures”, though, Grindler’s book is, like Sept’s, a little misleading. Not only are most treasure seekers unlikely to find quite as large cascades of sea glass as those that Grindler illustrates, but also, for the first nations artifacts, lucky will be the beachcomber, child or adult, who finds a single artifact in a lifetime’s searching! At the opposite end of the “treasure” scale, perhaps, is garbage — and Grindler is realistic and purposeful in including some of that, though, it has to be admitted, she limits herself to small bits and pieces, bypassing the detergent bottles, flip flops, and large plastic whatsits that spot many sections of the northwest coast.

Like all authors, Sept and Grindler face the task of engaging their readers not just with images, but also with text. In this regard, both writers clearly steer the tone and message in the overall direction of their differing notions of beachcombing. After a helpful and informative introduction, Sept settles down to the business of providing exactly the kind of details we would expect of a field guide — alternate common names, description, size, habitat, range and further notes. It is the notes that are most appealing to browse through, since it is in the notes that Sept comes up with some interesting tidbits — perhaps a morsel of cultural information or strange behaviour. Generally matter of fact and purposeful in describing location, distinguishing features, or feeding behaviour, he occasionally stirs to more emotional writing when pointing out the vulnerability of the species to damage from beachcombers or when showing real enthusiasm for a species’ beauty — of, for example, the rose star, or the frosted nudibranch. Two glossaries, one visual, one text-based, and an index, give exactly the kind of substance that even the most rigorous naturalist would want.

Grindler, in contrast, uses very little text. Parents looking for a book to read aloud might be a little disappointed at the paucity and brevity of text. Still, virtually everything Grindler writes is geared towards stirring fascination in children. Occasionally switching to first person (“Another of my favourite treasures”), she also includes some questions to make the young reader feel part of the treasure hunt. Generally eschewing information, except for the odd fact (“sea otters love to munch on [sea urchins]”], she becomes determined to impart knowledge only when writing about her run-a-way chief interest: sea glass. Thus, apparently, manganese in the glass making process gradually turns clear glass a soft lavender colour. Who knew?

Reflective of both authors’ sincere appreciation of the seashore experience, is the desire to protect it. Neither author goes very far in this regard, and, in fact, somewhat pull in different directions. Grindler encourages collecting, and even illustrates some ways of making crafts out of the treasures, even while also encouraging gathering and disposing of garbage. Sept, in contrast, specifically discourages collecting, especially of live specimens, but also gives detailed suggestions of ways to avoid harming shore life in the very act of “beachcombing.”

Despite such differences, both books share — and convey — a deep love of the seaside experience. Even without going much further in the direction of environmental protection, the way that both authors embrace the magic allure of the seashore can’t help but deepen environmental convictions in their readers. Now for a field guide for children, and, in contrast, a free-wheeling “beachcombing” book for adults!

*

Born on Vancouver Island, Theo Dombrowski grew up in Port Alberni and studied at the University of Victoria and later in Nova Scotia and London, England. With a doctorate in English literature, he returned to teach at Royal Roads, the University of Victoria, and finally at Lester Pearson College at Metchosin. He also studied painting and drawing at the Banff School of Fine Arts and at UVic. Theo Dombrowski is the author and illustrator of popular guide, travel, and hiking books including Secret Beaches of the Salish Sea (Heritage House, 2012), Seaside Walks of Vancouver Island (Rocky Mountain Books, 2016), Family Walks and Hikes of Vancouver Island — Volume 1: Victoria to Nanaimo, and Volume 2: Nanaimo North to Strathcona Park (Rocky Mountain Books, 2018), reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen in The Ormsby Review no. 384, September 25, 2018, and a Kindle book, When Baby Boomers Retire: Getting the Full Scoop. You can learn more about him from his website. Theo lives at Nanoose Bay.

Editor’s note. Theo Dombrowski came by his interest in the Pacific coastline honestly: his uncle, D.B. Quayle, wrote Pacific Oyster Culture In British Columbia (Ottawa: Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1969) and The Intertidal Bivalves Of British Columbia (Victoria: BC Provincial Museum, 1970).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster