#650 Love in vile places

Love in Vile Places: Military Hospitals as the Site of Care and Nurture

by Jo-Anne Fiske

*

For Remembrance Day 2019 we present a memoir by Jo-Anne Fiske of François Lake, in BC’s north-central interior, of her father Humphrey William Fiske (1886-1959).

At the time of his enlistment in Kelowna in 1916, the Norfolk-born Fiske was a “fruit rancher” (orchardist) in Summerland, on the west shore of Okanagan Lake. Wounded in 1918 at the Battle of the Drocourt-Quéant Line, Fiske recovered at a military hospital in England before returning to Canada the following year, where he developed an orchard of mixed tree fruits at Summerland. He married in 1934, when he was 48, and had three children, of whom Jo-Anne was the youngest.

Fiske examines her father’s experience in the straightened circumstances of a Canadian military hospital in England, where nurses encouraged “up-patients” — wounded men already up on their feet — to look after each other. She concludes that the lives and experience of First World War soldiers went far beyond familiar themes of wartime masculinity, sacrifice, and patriarchy. Her father’s experience, she notes, is also a world away from the “trauma tropes of Vietnam War models drawn from Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter,” which have nothing to do with Canadian experiences in the Great War. Fiske tells her father’s story first as a conventional narrative and then more analytically with reference to “haptic geography;” that is, writing that takes into account the sense of touch and related habits of care and nurture in wartime settings. – Ed.

*

I think it frets the saints in heaven to see

How many Desolate creatures on the earth

Have learnt the simple dues of fellowship

And social comfort, in a hospital

— Aurora Leigh, by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1857

*

A child cries in the night. Tosses her fevered body across her bed. Clutches her aching ear.

A low beam of light flickers across the floorboards squeaking beneath quiet footsteps. A gentle hand caresses her brow and inserts the thermometer between her lips. The gnarled hand now rests on her shoulder then slowly rises to her ear with eyedropper ready with soothing warmed clove oil. The thermometer shows a fever but not a dangerous one. The light now plays across her chest and then her back. There is no rash no sign of a disease that might steal her hearing. She lays back on her bed, her head on a fresh pillow, comforted.

The little girl in the crib beside her stirs and calls out. Now she feels the warm hands on her cool brow, the soft pressure of reassurance on her shoulders. She smiles as the light traces her back and chest, laughs at the nonsense words murmured in her ear. Closes her eyes to the last squeeze on her shoulder and returns to sleep. Her father leaves as silently as he came, checks his sleeping son, stops to stoke the fire and then slips into bed beside his sleeping wife. Tomorrow she will rise early to walk into town where she works packing the fall fruit and he will take up his routine chores in the house and orchard.

*

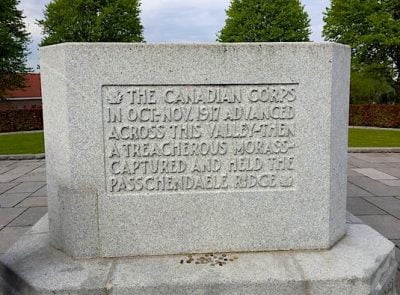

When I relate stories such as this one of my father caring for his young children, I am frequently reminded that he was an unusual man, ahead of his time I am told, a pro-feminist when feminism was not a popular issue. But when I reveal that my father, Private Humphrey William Fiske, was a veteran of the First World War — who enlisted with the Rocky Mountain Rangers in April 1916; who after long periods of hospitalization was a year later drafted to the Seaforth Highlanders as replacement for their horrific losses of 76 per cent of their battalion at Vimy Ridge; who fought with his Lewis gun team in the slimescape of Passchendaele in the famous taking of Crest Farm; and who was wounded September 2, 1918 at the Battle of the Drocourt-Quéant Line as the Canadian shock troops broke through the Hindenburg Line — I experience quite different reactions, ones imbued in the widely accepted tropes of shell shock and post-traumatic stress disorder as a defining, life-long attribute of war veterans. All too often when asked to speak about my father’s war service, strangers treat me with pity and compassion: Surely my father was a troubled man and my childhood ranged from the bleak to the violent, ever defined by the silent and awkward veteran?

A century has now passed since my father returned from war and it is difficult to reconstruct his life at that time. Like many British-born men who voluntarily served in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, he was a relatively recent arrival in Canada. By 1912 he was living in Summerland in the Okanagan Valley working on orchards. Summerland, on the south western shores of the lake, where land had been expropriated from the Okanagan First Nation, became the idealized settlement in the last years of the nineteenth century. Incorporated in 1906, the rapidly expanding district boasted electricity and telephone services, a college, and a range of strong cultural and sport associations. For a time, labour was cheap; British and Oriental farm labourers were readily engaged.

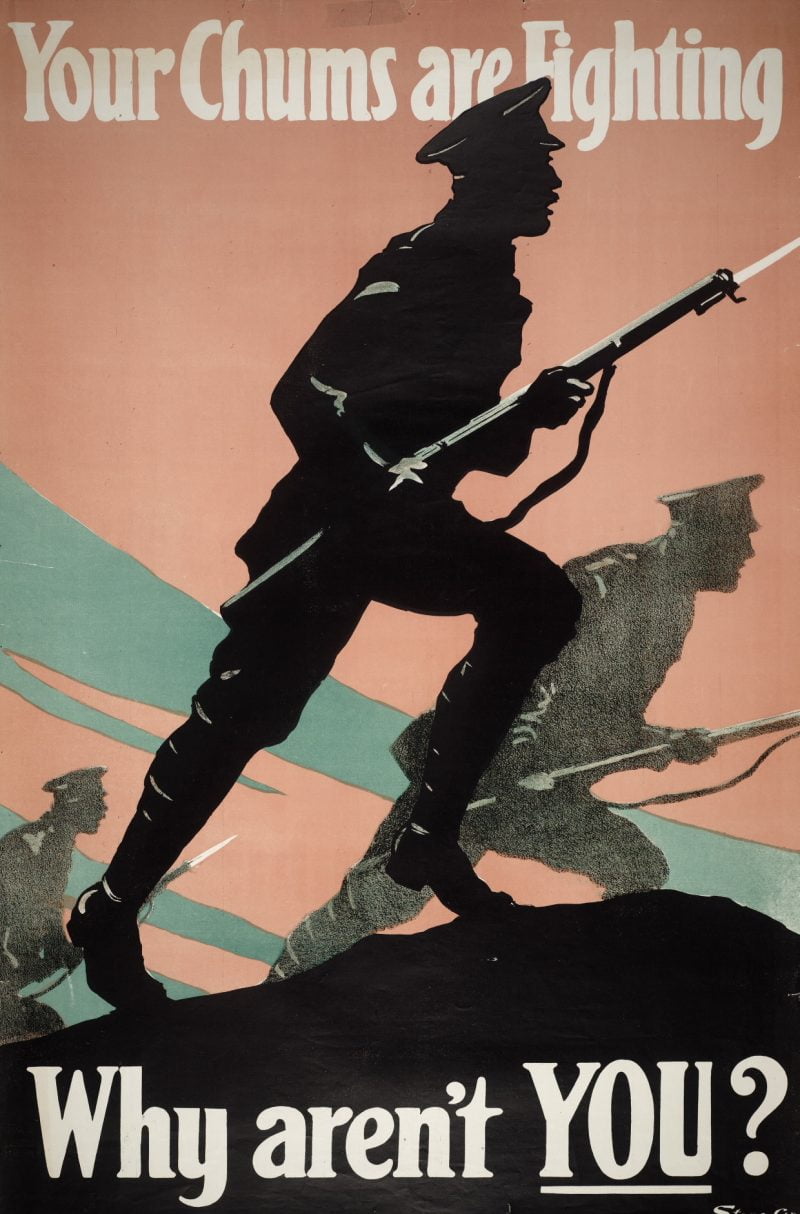

It was from here on April 3, 1916, after four years of working in the area, my father boarded a paddle wheeler northward to Kelowna where he enlisted in the Rocky Mountain Rangers. Why did he do so? His rationale decades later never invoked the master narratives of ideological patriotism of duty to God, King and Country. His answer was simple and short: Young men were being killed and wounded in large numbers, and he, now older at 30, felt he must go. He may have been influenced by the poem In Flanders Fields, which was now widely used to appeal to emotions, or a commonly displayed propaganda poster that blazoned “Your chums are fighting, why aren’t YOU?” Perhaps he followed friends into the fray, for we know that at least one family from his home town in England resided near to him. Although agricultural labourers like my father were in high demand at home and urged to remain, it is unlikely they did not feel the pressure to “do their bit” at the front. In 1916 The Rocky Mountain Rangers issued a small journal that condemned men shirking their duty and entreated all men who were able to enlist. The Rocky Mountain Rangers, moreover, was a unit of British migrants that had recently shifted its headquarters to Kamloops, just north of the Okanagan Valley, so in all likelihood he was among friends.

Had Father been tempted by army wages given the tumultuous climate of fledging commercialization of the tree fruits, his timing was unfortunate. As David Dendy shows, from 1912 to 1916 the industry had been ravaged by serious setbacks: declining prices in 1912 due to competition with the United States that lasted through the war years, oversupply and weak marketing strategies, and a recession in 1913. Wages declined severely, up to thirty percent from 1913 to 1915.[1] By the summer of 1916 that changed dramatically. So many men of the Okanagan had enlisted by the close of 1915 — 1800 had left the valley for the war — wages rose abruptly to $3 to $4 per day and remained high until well after the war ended, while privates’ wages in the infantry remained at $1.10 per diem when at the front. Whatever his personal motives, Father was soon on his way to Quebec, where the battalion received training.

His official records tell us very little. He sailed from Halifax on 25 October 1916 and arrived in England six days later. He was stationed at the Military Camp at Bramshott, Salisbury Plain, where he was hospitalized in an isolation ward at Aldershot with rubella in December 1916, only to return to the isolation ward in January, this time with measles and mumps, which left him partially deaf. When the Rocky Mountain Rangers were disbanded on January 1, 1917, he was transferred to the 24th Reserve Battalion. As with many others of the 172nd, when he went to the front he was drafted into the 72nd Battalion, The Seaforth Highlanders, from Vancouver, in keeping with Canadian strategy of building fighting units from men who had already developed comradeship. He arrived at Arras, France, on April 22nd shortly after the famous battle of Vimy Ridge, along with a fellow private, Guy Lepingwell from Cawston, BC, who remained his life-long friend. Apart from 14 days leave in December 1917, he stayed on the Western Front where he served as a Lewis gunner until September 2, 1918 when he was wounded on a day of heavy casualties at the onset of the 100 days leading to Armistice November 11, 1918. He suffered a gunshot wound to his right arm, a “Blighty,” the wound desired by many seeking escape from the fetid trenches of mud and corpses.

His wound took him through the now well-travelled evacuation route of casualties. From the battle field he was carried to the advanced dressing station and evacuated the same day to the casualty clearing centre at Arras. The next day he was transported by ambulance to the No. 7 Canadian General Hospital at Étaples. After five days he was placed on a hospital ship, Stad Antwerpen, for the Devonport military hospital. A month later, on October 14th he was transferred to the Woodcote convalescent centre at Epsom, which by then was the largest convalescent centre for the other ranks with 3800 beds. He remained at Woodcote undergoing treatment and therapy until December 4th when he received two weeks leave and was taken on strength in a reserve battalion at Seaford.

Finally, in January 1919, he began the long journey home. After a week in convoys of returning men all held at Kinmel Park, site of the infamous riots of bored and disaffected men caught in the liminal zone of being neither on active service nor discharged to civilian life, on January 18 he embarked on the Aquitania for Halifax. By early February he was at the Shaughnessy Military Hospital, Vancouver, from where he was honourably discharged “as medically unfit” on March 18, 1919.

His medical records indicate his wounds had healed in five weeks, although he continued to suffer pain and restricted mobility in his arm. Upon discharge, he was appraised as a “healthy looking well nourished young man…[who] eats and sleeps well and offer[s] no complaints except those referable to right arm and hearing…. He has constant pain (not sensation) in palm of rt. hand…. Will probably be able to resume occupation as fruit farmer.” Which he did.

Today we know little of his life during his service and after his return. Many of his personal records have been lost: greeting cards from his sister and brother-in-law in England, a photograph with friends from England presumably just before leaving for war as he is dressed in his Rocky Mountain Rangers uniform and a postcard from his younger brother, Harold (who served in the British Expeditionary Force until his death on the Western Front in 1918), while he awaited being shipped to the warfront are among the few documents that allow us to piece together his war time life. Gaps exist in his post war experiences as well. He returned to Summerland, where he lived as a bachelor for the next 15 years as he developed an orchard of mixed tree fruits. In 1934 he married a young woman, Rose Moore, who was 29 years his junior. It was not until thirty years after enlisting, now in his sixties, that his family was complete. He was now the father of two toddlers and an infant.

Father’s life followed a typical pattern in the Okanagan valley in the mid twentieth century. He and his wife worked the orchard and provided for the family with the usual gardens, chicken raising, and hunting. As the children grew, his wife worked seasonally in the local fruit packing plant and in the village stores. But what made Father unusual was his deep nurturing involvement with his young children. With the birth of his first child, he engaged in daily care from bottle feeding at night to diaper changing when his wife was visiting friends or volunteering in the community. When the children were small he pulled them in their wagons or winter sleds to visit neighbours or to the town library. He rose in the night to care for the kids when they were sick, walked to town to attend their special days at school, and took them fishing in the local creek.

He is also remembered for his deep devotion to and respect for his wife. She would often proudly say she was the only woman at the packing house to go home at the end of each day to a cooked meal. She was also rare in having her own bank account, and with Father’s approval was free to spend her money as she saw best. In short, our home life was much like that penned by Menzies in his 1917 humorous poem, The General, which depicts the reversal of gender roles on the British home front and the life of the stay at home husband/father. As the “general” proudly pronounced, so might Father have said:

I set to work; I rose at six;

Summer and winter; chopped the sticks,

Kindled the fire, made early tea…

I cooked the porridge, eggs and ham,

Set out the marmalade and jam,

And packed the workers off well fed,

Well warmed, well brushed, well valeted…

[And] when the sun had sought the West,

And brought my toilers home to rest,

Savours more sweet than scent of roses

Greeted their eager-sniffing noses—

Savours of dishes most divine,

Prepared and cooked by skill of mine.

The age differences between my parents shaped their social life. Age peers of my father were parents to my mother’s age peers, and across these generations family friendships were forged. Father’s social circle of fellow veterans within the town and further afield in neighbouring villages maintained a pattern of reciprocal visits; the former war comrades not only shared war time memories and sensibilities but also common interests of orcharding, hunting, and gardening. In this social milieu Father attended the annual Remembrance Day celebrations at the village cenotaph, and was active in the local branch of the Royal Canadian Legion.

In 1956 the town recognized him as a pioneer that was marked by 44 years of residency. At his passing in August 1959, the local Legion branch held special honours for him. To this day his grave is marked (as are all the veterans’ graves) by a metal poppy placed there by the Legion. Each November a burning candle is added. And a street is now named in his honour.

*

In recent years I have learnt that although my Father was exceptional among his contemporaries he was not unique. From 2014 through to 2018, I had occasions to meet with others in Canada and Britain whose fathers were veterans of the First World War and who fought on the Western Front. In Britain we came together rather casually. We met at a public gathering in London hosted by the Imperial War Museum and the British Film Institute and, although all strangers to one another, we soon shared poignant stories of our now long deceased fathers. Several common threads emerged from these stories that prompted me to question whether war experiences of these men shaped their domestic relations. All the fathers — and two grandfathers who had raised grandchildren — in question had entered the war unmarried, and did not marry for several years or more after their return to civilian life. All married women younger than themselves; age differences between the married partners ranged from approximately 15 years to just under 30 years. All of the fathers were “older parents” at the birth of their first child; with ages ranging from mid-forties through to the sixties. Significantly, all were either men of the “other ranks” or non-commissioned officers. None was an officer. And all had spent considerable time in hospitals during their service years, either as medical patients suffering from the communicable diseases that swept the ranks, or from wounds. A few had been in convalescent homes where they underwent a range of routinized rehabilitation practices to address disabling consequences of their wounds in preparation for return to civilian life. Could this shared experience have contributed to their exceptional family relations?

In 2015, the Wall Street Journal paid tribute to the work of First World War British visual artist, Stanley Spencer, located in the private chapel, Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere, Hampshire, England.[2] Inspired mainly by the Beaufort War Hospital, which he decries as “a vile place,” Spencer portrays hospitalized soldiers in a series of murals that:

[S]tart by emphasizing its dark, depressing drabness … the first small painting shows a shell shocked soldier throwing himself down to scrub the grubby floor with manic determination. Colors become more cheerful in “Sorting the Laundry,” where the men’s vigorous manipulation of billowing bed-linen, blankets and spotted handkerchiefs is presided over by a kindly nurse. Yet gloom returns in “Filling Tea Urns,” an activity carried out by patients who all seem preoccupied with loneliness. And we recoil from “Frostbite,” where orderlies like Spencer himself try to scrape the feet of bedridden patients….

“Tea in the Hospital Ward” is a celebration of irresistible bread and jam. Piled in thick slices on a table, this delicious food was supplied with a generosity reflecting the matron’s desire to indulge Spencer’s own appetite….

These bandaged figures all look desperately young, and Spencer stresses their devotion to helping one another. This brotherly compassion strengthens in “Ablutions,” dominated by a careful orderly who paints a naked soldier’s body with iodine. The tenderness is movingly conveyed, and on the opposite wall soldiers gather water from a Macedonian mountain while their cloaks float in the air like angels’ wings.

This feeling of tactile engagement runs through the entire cycle of paintings, made by an artist who knew, all too well, how savage and merciless modern combat could be. Despite everything he had witnessed in the hellholes of war, Spencer was defiant enough to make this chapel reaffirm the undying power of love….

Spencer’s affirmation of manly love and nurture stands in acute contrast to narratives that have variously constructed wartime masculinity in stark, often uncompromising, stereotypes: from the contemporary defining narrative of “muscular Christianity” extolling men of duty and sacrifice who followed the call of the nation;[3] to the silent veteran returning awkwardly to post heroic civilian life;[4] through to the traumatized veteran afflicted by shell shock.[5] Indeed, tropes of trauma, generalized assumptions of shell shock as a lingering disability, and emerging concepts of intergenerational trauma mark late twentieth century popular war imaginary and persist today, motivating a multidisciplinary quest to record and understand historical constructions of trauma.[6]

While we cannot dismiss the significance of the history of trauma, or the First World War’s central place within it, nor can we allow it to overshadow other approaches to understanding male experiences of warfare and their legacies for future generations. In a nuanced analysis of first person accounts of men and women of the war and the literature of the soldier poets, Oxford scholar and literary critic Santanu Das positions emotion and touch at the centre of a new understanding of intimacy in the trenches. “Bodily senses, particularly touch,” he asseverates, “define the texture of experience in the trenches and the hospitals and … inform and share war writings.”[7] This he argues constitutes a “haptic geography;” touch both replaces and heightens visual geography.

Whereas for Dawson,[8] confinement in the trenches was best explained as men hiding in holes seeking out other men hiding in holes, for Das touch between men of the holes, friend and foe alike, defined war experiences and shaped identities. Through exploring the intimacy of touch, he presents new understandings of gender and sexuality, of sensuousness and emotionality, which emerge “out of a very particular set of circumstances — a context of actual physical experience and extremity — and cannot be dissociated from them.”[9]

Das’s study of the sensibility of writers and artists of the war and immediate post war period draws from a range of contemporary expressions, from the literature produced during and immediately after the war, memoirs and letters of soldiers and sisters participating in the war, and from visual arts. In this essay I am influenced by Das and Spencer regarding touch and tenderness. While heeding Das’s caveat that the paradigm he has applied to literature by those who experienced the war cannot directly be applied to those who did not,[10] I seek to extend his understanding beyond the war experience to the civilian sphere.

Specifically, I accept Das’s constructions of emotion and tactile intimacy as commonplace and deeply meaningful in the trenches and hospital wards, but then ask: How do they configure in the development of domestic identity? What can be said about the significance of tenderness in the trenches and wards in shaping domestic relations decades later?

With reference to Spencer, who served as an orderly in military hospitals at the front and in England, and who described these institutions as “vile,” I ask: How does love emerge in vile places? Can deep emotions of love and empathy associated with the stench and sorrows of the wounded and dying persist after the horror is ended? Can there be, intertwined with the haptic geography of trenches and hospital wards, a meaningful space defined by routine activities that ground social relations through interdependence and shared identity?

Military hospitals of a century ago may indeed have fostered love as Spencer has depicted. In general, as others have documented and the war diaries and personal journals of hospital staff recorded, hospital wards for the ranks were sites of deprivation. From Salisbury Plain from 1915, where Canadian troops trained in inclement weather and suffered epidemics of contagious diseases, through to the convalescent hospitals where the disabled languished in 1919, men of the other ranks were dehumanized: subjected to rigid routines, humiliated by medical officers suspicious of malingering and brutalized by “treatments” of whipping, electric shock, and enforced physical exercises for shell shock and other nervous conditions, and subjected to rigid routines. Wrapped in the infamous hospital blues (a pyjama like suit without pockets), and cordoned off from fellow soldiers and civilian populations, they were marked as “other” — neither fully soldiers nor civilians. Restrictions on their liberty and staff perceptions of them as childlike deprived them of independent adulthood.

As always in wartime, the state was preoccupied with frugality, and men of the other ranks experienced this in illness and injury. Hospitals were either camps of tents or cabins, or converted large buildings including castles, churches, and exhibition halls. Wards for the other ranks were in general cavernous: poorly ventilated in hot weather, cold and damp in winter. Whether a base or stationary hospital in Britain to which the wounded were sent for recovery, or the field hospitals close to the front where they received initial treatment, they all suffered periods of staff shortages. In this social climate the men, as they did in the trenches, created their own social bonds and collective identities. With few staff to provide for their immediate physical needs in wards of fifty or more patients, the men relied on each other for reciprocal care and affection.

Personal diaries and letters from the female staff, primarily the volunteers with the Red Cross and St. John’s Voluntary Aid Detachments (VAD), describe, albeit sparsely, the caring practices that occurred patient to patient. Within these large barrack-like wards, men who were mobile provided care for those who were not. Touch was central to these relationships as ambulatory patients assisted the “cot cases,” that is the bedridden, with their cigarettes, feeding, wound dressing, and intimate needs. In time of emotional or physical anguish they comforted one another.

Central to these practices were the “up-patients,” men who were in an advanced state of recovery. Canadian volunteer Marjorie Starr, serving the Scottish women’s field hospital at the front, records how the staff relied on up-patients to do the heavy lifting when a rush of wounded arrived, to carry patients up and down stair cases for surgery, and to carry on the routine domestic tasks such as carrying pails of food to the wards at meal time.

Dorothea Crewdson, a British VAD, on staff in a base hospital in France, describes the chaotic conditions as Canadians arrived from Vimy in 1917. Wards were overfull with patients on stretchers “accommodated in odd corners on the floor and down the centre.”[11] In her division alone, on 14 April, over 100 patients were all on stretchers. In these moments up-patients were vital as the VAD/patient ratio might rise to an unmanageable ratio of 1:70, while supervising nurses were in charge of two or more wards. In the crises of care that arose after major battles even orderlies were in short supply, making the soldiers in duress even more dependent on one another.

A conundrum for medical staff was the conflicting need to empty beds prior to a “big push” to be prepared for waves of wounded and their reliance on able, skilled, and compassionate up-patients to perform essential caregiving tasks. Crewdson found herself in such straits in 1917 for more than twenty such men had been evacuated further down the line over the preceding months, all of whom in her estimation were good workers. After a large convoy of wounded arrived, she named a number of up-patients who were caring for the bedridden, attending to washing, assisting with long dressings, and helping to feed those who could not feed themselves:

Sergeant, Godfrey, Paddy, and Weeks worked splendidly in the afternoon getting washings and tidying done. They really are the most useful up-patients…. Sergeant and some assistants did the washing. So saved me all that. Have two more patients up today so there are plenty of helpers rendering valuable assistance.

She adds a few lines later, “Have got such a lot of up patients and some very useful ones.”[12]

Up-patients not only worked in the wards and kitchens supplying essential services to bedridden patients, they also demonstrated tenderness to and social solidarity with other patients. Crewdson continues, “The Nottingham Sergeant is most helpful and can get others to work, having got his promotion. Paddy does a good deal and talks a good deal and guffaws occasionally in the most inspiriting manner. He is a real old soldier, but quite entertaining.”

When her three most valuable up-patients were evacuated, Crewdson wrote, “Don’t know what we will do when they are gone.” She soon found herself left alone to do all the long bandages, and other routine tasks.

As they forged strong and friendly relations with VAD and medical orderlies, up-patients nurtured the spirits of the bedridden, more dependent patients. Lewis, for example, having been with Crewdson’s ward for seven weeks assisted in the kitchen and came to think of himself as part of the staff, and so he seemed to Crewdson. Friendly relations shone through on April Fools as Lewis pranked Crewdson to the amusement of the ward inmates.[13]

Starr’s and Crewdson’s description of the working up-patients echoes Spencer’s philosophy of the psychological benefits of routine labour, and resonates with Das’s insights on the intensity of touch and intimacy men experienced in these close quarters. However, up-patients not only nurtured through routine caregiving and general housekeeping tasks, which drew out tenderness towards fellow patients, they also were central to social and cultural events that staff promoted to distract the suffering from their anguish and loneliness. Up-patients engaged in holiday celebrations as they decorated wards at Christmas, organized theatrical programmes with orderlies, and in general contributed in a myriad of ways to offset the otherwise grim daily existence of wounded men crowded together in discomfort and hardship. In short, the vile places Spencer memorializes were sites of tenderness, intense emotion, and social unity.

The official war diary of Bramshott Military Hospital at Salisbury Plain provides greater insights as to the necessity of patient-to-patient care in times of grim deprivation and in doing so reveals the significance of touch and emotion to the patients’ well-being.[14] By 1917, all of Britain was suffering a shortage of food; the military a shortage of men to replace the wounded and dead; the hospitals a shortage of staff and financial support. In these hard circumstances men of the other ranks were placed on a very limited daily diet: a half-slice of bread twice day, thin jam, weak tea, meat-thin soups, and porridges. As deprivations of the country ground on, military hierarchies did what they do best: counted the minutiae of wastages, of their soldiers, their resources, and of their food and garbage in fine-grained detail. The military made contracts with locals to sell them all the fat from the men’s meat for tallow. Fat was trimmed from meat to be sent to rendering plants, food garbage was retrieved to be sold as pigswill, and paper trash traced for recycling. Unannounced frequent inspections were made of the kitchens and garbage tips to ensure this was followed.

All of this generated credits that were then used for patients’ rations. Uneaten portions of meals (half-eaten pieces of bread, for example) were carefully hoarded to be re-served. Food waste was inspected and weighed and picked through. Patients were not allowed to hoard uneaten portions of their food, but at the same time a half slice of bread might circulate more than twice through the wards, each time trimmed a little smaller to cut away any tooth marks left on it. Peelings from vegetables were as likely to find their way to the stockpot as to the swill bucket. The patients were malnourished, hungry, and bored. In short, the Bramshott war diaries show a military that was cruel in its response to the crisis and created even worse deprivations for the disregarded other ranks.

Hospital administrators went to great lengths to maintain as many of the up-patients as possible to replace orderlies who were leaving for the front lines. Bramshott’s War Diary details how surgeons and other medical staff selected patients who had the caring “touch” and could be entrusted with a range of duties that included assisting with dressing wounds, feeding patients with arm and hand injuries, and assisting others to dress, walk, and bathe. At another hospital, in October 1918, Nurse Edith Appleton noted in her diary, “only 20 trained people for about 2,000 beds is not enough;” and lamented that “two blue boys” whom they had trained to help with dressings had taken ill. In winter it was these patients who throughout the night often maintained the fire-burning heaters in the wards, worked in the kitchens at dull routine work that the chefs needed completed, and assisted in the general maintenance of the wards.[15]

Beyond being assigned specific duties to maintain necessities of the medical care, patients also created a vibrant social space. Assisted by the nursing staff and at times outside volunteers, they arranged entertainments for themselves, read and wrote letters for the ones who could not do so themselves, and held games and contests within and between the wards.

In these social relations of care and nurture, life in the wards transcended gender stereotypes of civil society; the world of the wards, and indeed much of life in the trenches, placed soldiers in domesticated space where skills of survival and sociability were stereotypically feminine. Not only were routines defined by household tasks, social relationships were founded in emotions of care and love. Domesticity of trenches and hospital wards no doubt provided a skill set, and even an emotional template, for the veterans’ post-war bachelorhood and eventually their status as exceptional and unusual husbands and fathers.

*

Sixty years have gone by since my father passed away. Memories of his voice have faded, the details of his stories confused, his friends’ names forgotten. But the cool cloth on a fevered brow, watching his work-roughened hands baking fruit pies in a fire-hot kitchen, and walking hand-in hand to neighbours are moments that remain bright and clear. His legacy lives on in nuanced ways. From Father we learned the love of tending vegetable beds and rose bowers. Due to his years of service and his wounds, all three of his children received Department of Veterans Affairs post-secondary education sponsorship. Our mother benefited from the relatively small, but to her significant, widow’s pension until her passing in 2015, aged ninety-nine.

Haptic geography allows me to see my father in a more rounded light and places him in a context of care and support to others that was mirrored in his family life four decades later. The tenor of everyday family relations of returned men who were never seen as exceptional in the trenches but who are recalled as unusual by their children speaks to a different legacy of The Great War than those encoded in contemporary narratives of supreme sacrifice, masculinity, and patriarchy. Nor does it resonate with the trauma tropes of Vietnam War models drawn from Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter.

The memories families hold of domesticated men married to independent women also call into question tropes of masculinity underlying other interpretations of wounded veterans. In tracing veterans’ struggles for pensions, historian Desmond Morton misses the mark when he notes, “In 1930, a woman unwise enough to marry a man after he was disabled finally won a guarantee of support” as the government’s “fear of ‘widow pensions’” was overcome (my emphasis). [16] But women wise in marrying their remarkable husbands were unlikely to have done so in the hopes of obtaining a small pension at some unknown time in the future. For some, the rewards were remarkable.

*

Jo-Anne Fiske was raised in Summerland. She studied at UBC, first taking a degree in Education (sponsored by the Department of Veterans Affairs), which led her to a short but delightful elementary school teaching career in British Columbia and England. She returned to UBC to complete an MA and PhD in Anthropology. She taught at several Canadian Universities from coast to coast and recently retired from the University of Lethbridge, where she holds the title of Professor Emerita in Women and Gender Studies. She has worked extensively with First Nations in central British Columbia and has published numerous works, many co-authored with members of these communities, that speak to issues of justice, health, and traditional land use. She now lives on the northern shore of François Lake where she continues her research and writing.

*

Sources:

Appelton, Edith 1916-1919. “A Nurse at the Front.” Diary. Copy held by author.

Babington, Anthony 1997. Shell-Shock: A History of the Changing Attitudes to War Neurosis. London: Leo Cooper.

Bramshott Military Hospital 1917-1919. “War Diary. War diary, 15 Feb. 1916 – 2 Aug. 1919.” Library and Archives, Canada. RG 9 III-D-3, vol. 5036.

Cook, Tim 2008. Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War 1917-1918. Toronto: Viking Canada.

Cork, Richard 2015. “War’s Pain Redeemed Through Art: Stanley Spencers’ Paintings in the Sandham Memorial Chapel.” The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/wars-pain-redeemed-through-art-stanley-spencers-paintings-in-the-sandham-memorial-chapel-1422056363

Crewdson, Dorothea 2013. A First World War Nurse Tells Her Story. London: Phoenix

Das, Santanu 2005. Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dawson, Coningsby 1917. The Glory of the Trenches. www.gutenberg.org/etext/7515.

Dendy, David 1989. BC Tree Fruits Association. Kelowna, BC: BC Tree Fruits Association. http://www.bcfga.com/317/Author’s+Note

Dobbs, W. E. 1917. Personal Correspondence. Copy held by author.

Humphries, Mark Osborne 2018. A Weary Road. Shell Shock in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. 1914-1918. Toronto: U of T Press.

Loughran, Tracey 2010. Review of Masculinity, Shell Shock, and Emotional Survival in the First World War, (review no. 944) http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/944.

Menzies, George Kenneth 1988 [1917]. The General. Never Such Innocence: A New Anthology of Great War Verse. Martin Stephen, ed. London: Buchan and Enright.

Meyer, Jessica. 2009. Men of War: Masculinity and the First World War in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Morton, Desmond, 1993. When Your Number Is Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War. Toronto: Random House.

Roper, Michael 2009. Masculinity, Shell Shock and Emotional Survival in World War I. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

Starr, Marjorie 1915-1916. Private Papers of Miss M Starr. London: Imperial War Museum. Documents. 4572.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] David Dendy, 1989. BC Tree Fruits Association. Kelowna, BC: BC Tree Fruits Association. http://www.bcfga.com/317/Author’s+Note

[2] Richard Cork, 2015. “War’s Pain Redeemed Through Art: Stanley Spencers’ Paintings in the Sandham Memorial Chapel.” The Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/wars-pain-redeemed-through-art-stanley-spencers-paintings-in-the-sandham-memorial-chapel-1422056363

[3] Coningsby Dawson, 1917. The Glory of the Trenches. www.gutenberg.org/etext/7515.

[4] See Michael Roper, 2009. Masculinity, Shell Shock and Emotional Survival in World War I. Manchester: University of Manchester Press, and Jessica Meyer, 2009. Men of War: Masculinity and the First World War in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[5] Anthony Babington, 1997. Shell-Shock: A History of the Changing Attitudes to War Neurosis. London: Leo Cooper.

[6] See Meyer, Men of War; Tim Cook, 2008. Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War 1917-1918. Toronto: Viking Canada; Tracey Loughran, 2010. Review of Masculinity, Shell Shock, and Emotional Survival in the First World War, (review no. 944) http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/944; Mark Osborne Humphries, 2018. A Weary Road. Shell Shock in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. 1914-1918. Toronto: U of T Press.

[7] Santanu Das, 2005. Touch and Intimacy in First World War Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 230.

[8] Dawson, The Glory of the Trenches.

[9] Das, Touch and Intimacy, p. 231.

[10] Das, Touch and Intimacy, p. 232.

[11] Crewdson, Dorothea 2013. A First World War Nurse Tells Her Story. London: Phoenix, p. 206.

[12] Crewdson, A First World War Nurse, pp. 88-89.

[13] Crewdson, A First World War Nurse, pp. 202.

[14] Bramshott Military Hospital 1917-1919. “War Diary. War diary, 15 Feb. 1916 – 2 Aug. 1919.” Library and Archives, Canada. RG 9 III-D-3, vol. 5036.

[15] Appelton, Edith 1916-1919. “A Nurse at the Front.” Diary. Copy held by author.

[16] Morton, Desmond, 1993. When Your Number Is Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War. Toronto: Random House, p. 274.

2 comments on “#650 Love in vile places”

Comments are closed.