#627 Out of a Danish orphanage

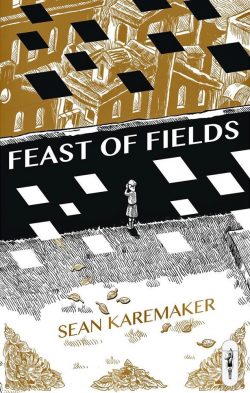

Feast of Fields

by Sean Karemaker

Wolfville, NS: Conundrum Press, 2018

$18.00 / 9781772620252

Reviewed by Chris Fink-Jensen

*

Feast of Fields, by Vancouver artist Sean Karemaker, is a graphic biography that tells the story of his mother’s childhood experiences living in an orphanage in Denmark.

Feast of Fields, by Vancouver artist Sean Karemaker, is a graphic biography that tells the story of his mother’s childhood experiences living in an orphanage in Denmark.

The book begins from Karemaker’s own perspective, recounting a time in childhood when he experienced the anxiety and loneliness that comes with being the new kid at school. To anyone who has been bullied this aspect of the story will feel eerily familiar. The author vividly captures his childhood state of mind during that time — slinking around hallways, keeping a low profile, trying, in effect, to become invisible. Efforts which, of course, only drew the attention of the mean kids. His refuge during those days came at lunchtimes when his mother would meet him in an upper field for picnics (hence the book’s title) and check in with him about his day. As Karemaker writes, “She knew that I was in need of some kind of sanctuary and she provided it for me, there in the grass.”

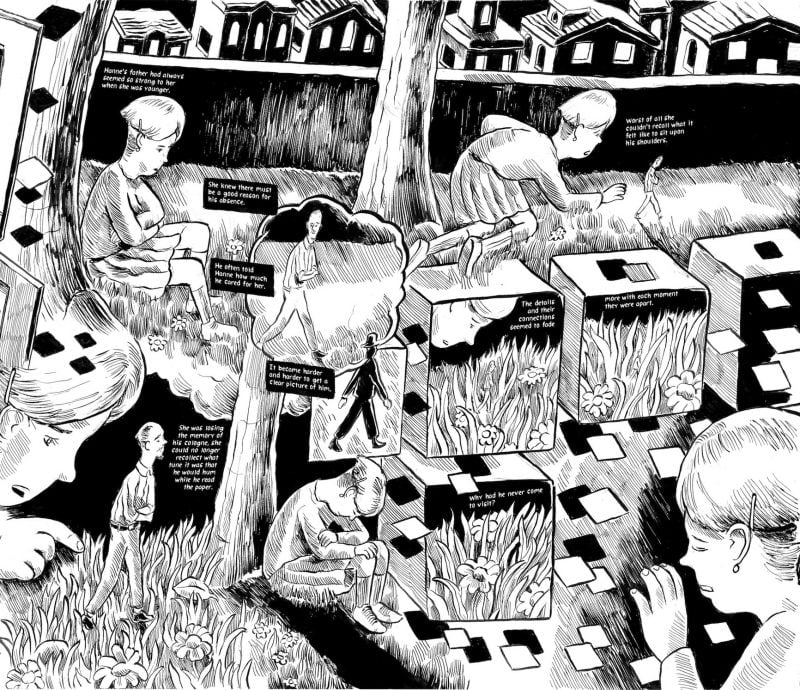

Inevitably, though, his mother’s support and attention is not enough to save him from his bullies. An altercation ensues and Sean winds up in the principal’s office before being sent home. The story might easily have continued in this vein, detailing how Karemaker dealt with his bullies. Instead, the story jumps through time (both real and imagined) while the perspective gradually shifts from Sean to his mother, Hanne.

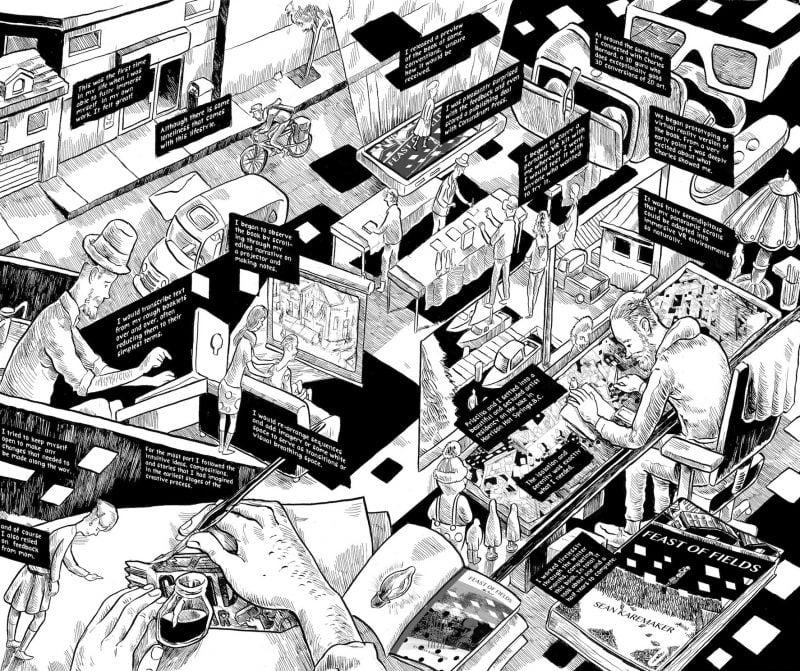

These shifts are a little unsettling initially, perhaps because this sort of episodic, non-linear storytelling isn’t what most readers are used to. It doesn’t take long, though, to get accustomed to Karemaker’s narrative style. Especially when one realizes that each sequence corresponds to the artwork on a real life panel which has been sliced to accommodate the page spreads of the book. In other words, each sequence is its own self-contained mini-story. And it is the artwork which truly lifts the narrative from a spare telling of a girl’s experiences of life in a well-meaning orphanage (interesting but not gripping) into a surreal, or perhaps hyper-real, blending of true history, meta-narrative, and imagination.

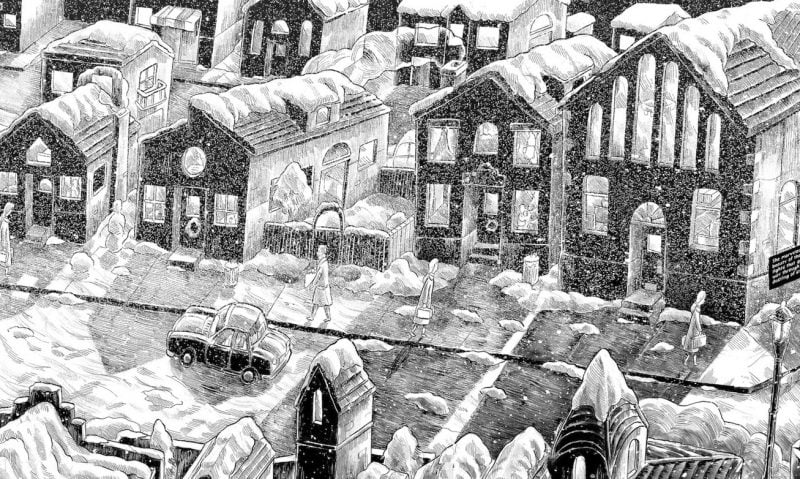

Karemaker’s gorgeous black and white artworks effectively support the text but are so much more than mere illustrations. Each page is a wonderland of interesting details. Fully furnished rooms. An old cabinet filled with keepsakes: a doll, a locket, a black and white photograph which becomes, in a more than literal way, a snapshot of Hanne’s world at seven years old.

Throughout the book Karemaker’s illustrations play free and loose with proportion and perspective, a technique which lends some of the panels an Escher-like quality that is both fascinating and a little haunting. It’s a style perfectly suited to young Hanne’s experiences at the orphanage — from being forced to eat the whole of very distasteful dinner, to meeting a man through a hole in the wall of the outer yard, to struggling with being separated from her brothers, meeting new friends, and wondering what the future would bring. The intricacy of Karemaker’s art makes the orphanage a place that we, too, can explore and wonder about. Creating, as the book says, “a world in itself, separate from the rest of town.”

It’s not surprising, then, that despite missing their parents terribly, Hanne and her brothers wind up enjoying many aspects of their life at the orphanage, especially the friends they make, the freedom of the yard and, most of all, the predictable stability of life in an institution. As the narrator puts it, “Within these walls they may be independent. No longer captive to the events that brought them there, or to the adults who had left them.”

In this sense, the orphanage functions for Hanne the way she herself would later function for her son, Sean. During a transitional phase of childhood each provided a sanctuary from a looming, uncertain future. “There was a whole world beyond the wall,” Karemaker writes. “And she worried it would be hard for herself to remain a child as the reality she knew continued to change. She wanted it to stay the same, if only for a little while.”

In Feast of Fields these kinds of psycho-emotional insights are often played off against mundane events, like a pickup game of soccer or a moment alone under a starry sky. This balancing act is, in my opinion, another strength of the book. Karemaker has constructed a visual-textual narrative that closely mimics the actual experience of remembering. For example, if I think about my own childhood, it tends not to be in broad brush strokes but in specific, often mundane, episodes that have, for some unknown reason, stuck in my memory and become sentimentally significant. The blue snowsuit I wore at four years of age when I met the girl who would become my best friend. Or the morning I decided I could make instant oatmeal in a mug but, not knowing how to boil water, simply used cold milk. Or what the knob on my childhood black and white TV looked like and how it felt when I clicked it on — at 6 a.m. when my parents were still asleep.

In the same way, Feast of Fields is not a linear story but rather an impressionistic medley of important moments in Sean and Hanne’s lives. I would say, however, that the story might have been strengthened by moments of strong emotion, such as anger, fear, or joy. For the most part, characters’ feelings are mentioned and drawn via facial expressions, but the overall tone of the narrative, with the possible exception of Sean’s run-in with his bullies, is quite unvaried. Still, this is a fascinating biography. Readers will come away feeling they have visited a new place and perhaps even understand something about how another two other people, Hanne and Sean, came to be who they are.

One small criticism of Feast of Fields is that there are no page numbers, though given the intricate beauty of Karemaker’s artwork I suppose I can understand why that choice was made.

Finally, it should be noted that Conundrum Press has done a wonderful job producing a gorgeous book at an affordable price. In an age where pulp novels (or e-books!) often cost $25 or more, $18 for such a finely made, visually attractive volume is remarkable. This is a book that warrants many revisits — especially to admire Karemaker’s intricately composed artwork.

My own copy of Feast of Fields will live separate from my overloaded bookshelves in its own kind of orphanage on a living room side-table.

*

Christian Fink-Jensen is a writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. His work has appeared in more than fifty newspapers, magazines, and journals around the world. He is the author and co-researcher of Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer (Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2016), reviewed here in the Ormsby Review. In 2017 Christian was a finalist judge for the CBC’s Nonfiction Literary Awards. Christian lives in Victoria, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster