#621 A new David Thompson

Lines on a Map: Unparalleled Adventures in Modern Exploration

by Frank Wolf, with a foreword by John Vaillant

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2018

$25.00 / 9781771602891

Reviewed by John Gellard

*

On September 6, 2019, Frank Wolf’s Lines on a Map was one of five books shortlisted for the Banff Mountain Book Competition in the Adventure Travel category. The winner will be announced on October 31 at Banff Centre Mountain Film and Book Festival.

From North Vancouver, Frank Wolf is also a filmmaker and environmentalist –Ed.

*

Ben and I dove after the canoe and wrestled it into an eddy, untied the gear and began throwing it onto shore. A wave surge from the rapids hit and tore the canoe loose again. Ben grabbed the boat. One bag and a camera broke loose and floated downstream. I swam after them, plucked them from a tangle of branches along the river’s edge and heaved everything onto shore. When I inspected the canoe, I found a metre long hairline crack in the centre of the hull. In addition, the river had claimed our map.

Ben and I dove after the canoe and wrestled it into an eddy, untied the gear and began throwing it onto shore. A wave surge from the rapids hit and tore the canoe loose again. Ben grabbed the boat. One bag and a camera broke loose and floated downstream. I swam after them, plucked them from a tangle of branches along the river’s edge and heaved everything onto shore. When I inspected the canoe, I found a metre long hairline crack in the centre of the hull. In addition, the river had claimed our map.

That’s a tiny slice from one of two dozen stories in Lines on a Map. Frank Wolf, the author, and Ben O’Hara have been canoeing upstream on the Babine River. They’ve battled rapids in full flood, whirlpool eddies, and three-metre standing waves. They have been forced to turn back down the Babine and find another way east via the Skeena valley.

Are you a canoeist, a kayaker, a hiker, a skier or a cyclist? You might have attempted the impossible and got yourself into a few scrapes. Have you lost your GPS in a trackless wilderness? Have you had your canoe smashed against a boulder? Been feasted on by clouds of mosquitoes as your portage becomes an overgrown quagmire and you’re carrying a canoe and a 75 pound pack? If so, you will cheer as you read Wolf’s humorous and exciting narratives. If not, you will be inspired by his sheer strength and indomitable will to prevail.

The lines on Wolf’s map cover Canada from Labrador to Haida Gwaii and from the high Arctic to the Great Lakes, they cross Norway and Sweden, they trace the killer highway across Java, navigate the Thai coastline, and explore a remote Java wilderness.

All the journeys are propelled by human physical power alone — canoe, kayak, skis, bicycle, legs. Any motorized transport is used simply to get to the starting point. “The common thread is the pure joy to be found in stepping outside your comfort zone and breathing life into a line on a map.”

Pushing yourself to the limit is indeed the first “common thread,” but that’s a modest claim. Other equally important threads weave themselves into the fabric of the book, making a pleasing and fulfilling pattern.

The second thread is the idea of doing what has not been done before. Wolf eschews “bucket list” endeavours like climbing Mount Everest. “Objectives have to be obscure, remote, and off the radar to truly be considered adventures. There’s nothing adventurous about the well-known.

The third thread is the filming. Wolf filmed nearly all of his journeys. He’s got some thrilling “selfies” of shooting rapids, He’s got an amusing shot of himself disguised as a mosquito. He documents life in remote communities, and his work is broadcast regularly on CBC’s documentary channel.

Fourth, there are insights into the effects of modernity on the wilderness.

How have inventions like the outboard motor changed life for the people who live in the boreal forest? Has the damming of rivers in the north made a difference?

Thread five is the encounters with remarkable people: travelling companions, First Nations elders and youth, and Pierre Trudeau, to mention a few.

*

Frank Wolf and Lance Weathers are the first people to canoe across Canada in one season – 8,000 km from Saint John to Vancouver. It’s 1995, and Pierre Trudeau has invited them for lunch — chicken gyros in a Montreal cafeteria. Trudeau, an ardent canoeist, was excited by their trip. He declined media involvement. “His eyes turn to dead lumps of coal when politics and the media are brought up, but he’s an illuminated soul when we chat about canoe tripping.” The canoeists are of course paddling upstream on the St Lawrence and they have to find a way to paddle around the Lachine rapids. Trudeau solves this problem for them, and they are on their way for another 145 days to Vancouver.

Lance is an intriguing character, full of exciting stories. He tells of rescuing his beautiful tree-planting partner from an angry mama grizzly by shooting the bear point blank with three shotgun slugs. There’s a surprise outcome that the reader will enjoy.

*

“We scramble to put on bug jackets and DEET, hurriedly brush our teeth and dive into the tent. About a hundred of the vermin enter with us, and we slap crush and smear them all over the inside walls …. An inch-thick layer of the kitturiaq black out the mesh above our heads …. We slip into slumber to the bedtime lullaby [of their chorus]”

Yes, Frank and Rob are in the “Big Wild” — that vast swath of Taiga in northwestern Ontario where man is “peripheral to nature.” They are going up the Bloodvein River, and will descend the Severn, 981 kilometers down to Hudson Bay. They meet Enil Keeper of the local band council.

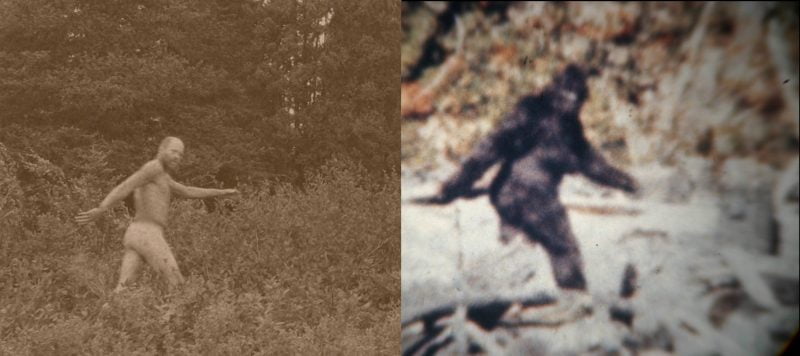

“How about Sasquatch? You guys seen any Sasquatch?” Enil has encountered them. He has not actually seen one, but he knows they are there.

This is a head-scratcher. One thinks of Sasquatch as strictly a West Coast thing. What are they doing in Northern Ontario?

Ennis Fiddler, an Oji-Cree elder says, “The idea of the Sasquatch is relatively new, there’s nothing in our oral history about it.”

So why has this “legend from somewhere else” suddenly taken root in Ontario? This is grist for an interesting discussion. Could the advent of air travel and the outboard motor, and the subsequent disappearance of portages between the myriad lakes made the wilderness wilder — fertile ground for the Sasquatch legend to grow?

Frank and Shawn discover a similar transformation as they canoe from La Ronge to Baker Lake They stop for supplies in Lac Brochet. A couple of Dene kids are fascinated by their canoe. They’ve never gone canoeing before. That’s a surprise because the Dene used to be “the finest canoe men in the north.” An elder explains, “We’ve unfortunately lost that tradition.” The modern convenience of motorized boats — more a curse than a blessing — has taken away the intimate connection with the land and traditions including the native language, setting the culture adrift.

*

Ocean kayakers will be inspired by two trips on exposed coasts in places half a world apart. Todd, Keith and Frank circumnavigate Haida Gwaii. They want to put in at the abandoned Puffin Cove homestead on the west coast of Moresby Island. Not easy in the heavy swell.

If I let the wave take me, I’d instantly surf seven metres down the face and pound into the trough at the bottom, submerging my kayak half way.

Do the kayakers make it into the sheltered bay? It’s a fascinating episode vividly narrated.

On the wild west coast of Java, Dave and Frank put together their Klepper kayak and set off around the stormy cape of Ujung Kulon.

We paddled hard for land, trying to work through the strong suck-back off the beach before the next wave hit…. A six-metre beauty came quickly behind us … and held the Klepper completely vertical before body slamming us face first into the surf.

If they lose the kayak here and stay alive, it’s several days’ hiking through the jungle to the road out at Taman Jaya.

*

Those are some details of a few of Wolf’s stories. You will also want to read about the bike trip along Java’s killer highway exploring volcanoes as friendliness turns to hate in the wake of 9/11, and about biking along the frozen Yukon River to Nome. You’ll find out about the 51st parallel that protects northern Ontario from destructive development, and about the threat to the Albany River where dams could destroy a way of life. “It’s our highway. It’s how we survive — our fishing and hunting, everything.” You’ll follow the Viking trail, portaging across Norway, and canoeing across Sweden to the coast of Finland. Canoeing, biking and hiking, our travellers follow the route of the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline, which was to transport “dilbit” from the “Mordor-like tar sands” to the Coast. And what would you do if you if you lost your money belt containing credit cards, money, travellers’ cheques and passport after sneaking onto a sacred island on the Thailand coast?

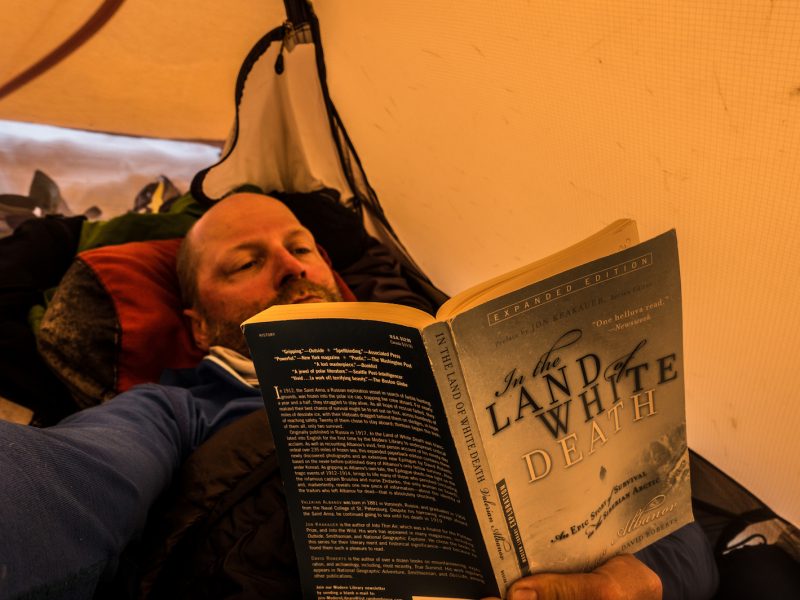

Let’s give the last word to Taku Hokoyama, “He is the ultimate soldier … staying in the moment,” says Wolf. Taku had left his wife Ednoi and his seven-week-old son Ashitaka to accompany Wolf on a seven-week journey through the boreal.

When asked if he ever thought about his family during the day, Taku says:

I can’t not think about them. I think about them every day, and miss them more than I could have imagined. At the same time, though, it’s worth it. The landscape we experience, the people we speak to — it’s an education no university can teach. The lessons I learn out here will form and inform how I raise my kid.

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.