#604 BC Hydro’s destructive legacy

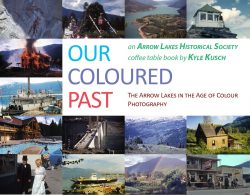

Our Coloured Past: The Arrow Lakes in the Age of Colour Photography

by Kyle Kusch

Nakusp: Arrow Lakes Historical Society, 2019

$30.00 / 9780969423683

Reviewed by Duff Sutherland

*

In Our Coloured Past: The Arrow Lakes in the Age of Colour Photography, Kyle Kusch presents 350 colour photographs from the collection of Nakusp’s Arrow Lakes Historical Society. The photographs illustrate the transformation of the Arrow Lakes and Upper Lardeau regions from 1940 to the present. The core of the book’s images documents the massive change that BC Hydro’s Arrow dam (later renamed the Hugh Keenleyside dam by the provincial government in honour of BC Hydro’s co-chair), built as part of the terms of the Columbia River Treaty, brought to Arrow Lakes communities in the 1960s and 1970s.

In Our Coloured Past: The Arrow Lakes in the Age of Colour Photography, Kyle Kusch presents 350 colour photographs from the collection of Nakusp’s Arrow Lakes Historical Society. The photographs illustrate the transformation of the Arrow Lakes and Upper Lardeau regions from 1940 to the present. The core of the book’s images documents the massive change that BC Hydro’s Arrow dam (later renamed the Hugh Keenleyside dam by the provincial government in honour of BC Hydro’s co-chair), built as part of the terms of the Columbia River Treaty, brought to Arrow Lakes communities in the 1960s and 1970s.

In the early part of the book, the photographs reveal how the province’s postwar boom driven by the exploitation of resources and the construction of the infrastructure changed the Arrow Lakes region in the 1940s and 1950s. The boom mostly bypassed the Upper Lardeau’s mining communities that continued their long decline. Change accelerated in the 1960s, however, as W.A.C. Bennett’s Social Credit governments came to see hydro-electrical power as the key to the province’s future prosperity. The government would use “brute force technologies” including large dams to generate revenue, attract industry, and improve living standards; on the Arrow Lakes, however, the Arrow dam had a profoundly negative impact on people’s lives as the rise in water levels flooded communities and farmland.[1] Our Coloured Past provides a remarkable visual record of the effects of this postwar capitalist development on the people and communities of the Arrow Lakes and, to a lesser extent, Upper Lardeau. Kusch’s detailed captions that explain the context of each photograph greatly enhance the visual narrative.

The photographs of the 1940s and 1950s reveal well the effects of postwar economic change on the region. Postwar immigration, the expansion of logging and mining operations, and a rising demand for farm products led to the growth of Nakusp, the region’s largest town. Expanding production that led to a growth in jobs and prosperity also contributed to a rapid rise in the number of cars, trucks, and buses that made use of the region’s newly-built and expanded roads, highways and bridges. By the early 1960s, photographs of downtown Nakusp show paved roads, parked and driving cars, and an emerging consumer economy in the form of new cafes, restaurants, a motel, and a movie theatre (see photographs on pp. 82-85, 209). At the same time, trucks, bulldozers, tractors and tug boats appear in images of farming and logging operations (pp. 87-89).

In the 1890s, mining and railway capital had created the region’s “roaring days” of mines, smelters, orchards, and sawmills that relied on railway and sternwheeler transportation. By the 1950s, the increased use of cars and trucks led to a decline in railway and sternwheeler service. Our Coloured Past documents well the fate of the sternwheeler the S.S. Minto that made its final trip in 1954 after 56 years of service to the people and communities of the Arrow Lakes (pp. 31-38). A Galena Bay settler, Walter Nelson, whose father, John Nelson, had purchased the decommissioned S.S. Minto, eventually organized the ship’s famous 1968 “Viking funeral” as the waters rose in the new Arrow Lakes reservoir (pp. 185-187). By the 1970s, for many in the region the photographs of the fiery “death throes” of the Minto came to represent the end of an era.

The Columbia River Treaty led to even more drastic change for the Arrow Lakes beginning in the 1960s. At least a third of all the photographs in Our Coloured Past focus on the clearing of land for the Arrow Lakes reservoir including the burning of many houses and the relocation of the communities and people “in the way.” In some cases, BC Hydro created new nearby communities above the planned high water line, in other cases, Hydro forced entire communities to relocate to larger centres, and, in still other cases, Hydro provided limited assistance to communities that would be partly flooded. The photographs of vacated communities, of cleared villages sites, of burning houses, of flatbed trucks and barges moving houses and community buildings, and of the dramatic change in water levels between an empty and a full reservoir suggest the devastation and disorientation experienced by the people of the Arrow Lakes through the 1960s.

Some unforgettable images include Rose Rohn seated in front of her burning home in Renata, the smouldering debris piles of the former community of East Arrow Park, the Anglican church, St. John the Divine, atop a barge in the middle of upper Arrow Lake, and the flooding of Chris and Jean Spicer’s once beautiful Nakusp farm (pp. 157, 149-150, 163, 184, 206-207). Kusch suggests some positive change came as “new” Edgewood eventually regained its former community spirit, Nakusp grew as the economy boomed during the dam-building period, and the province’s highway building and creation of new parks throughout the region led to increased tourism by the 1970s and 1980s.

However, in light of the 1960s photographs, the examples suggest that people and communities made the best of a bad situation. In 1961, Hazel Stark voiced the anger of the people of the Arrow Lakes at a water licence hearing in Vancouver: “This is just a hearing. When is there to be an answering?”[2] Absent from Our Coloured Past are photographs of the people in the way, like Stark, Chris Spicer, and Lottie Morton in the act of resisting BC Hydro’s expropriation and flooding of their property.

The province’s support for industrial capital through power generation created the “modern” Arrow Lakes after 1970. In this period, large-scale industry became concentrated in the large sawmill and pulp mill in Castlegar, and in the smelter in Trail. The Arrow Lakes economy, on the other hand, became focused on logging and on providing services and on tourism. Kusch points out that Nakusp continued to grow as the main service and tourist centre of the region into the 1990s. Photographs from the 1970s and 1980s show the town’s new large supermarket, airstrip, community sports centre, and breakwater and marina (pp. 208, 265, 269, 295). New and expanded highways and roads also brought in tourists attracted by the beauty and history of the region. Photographs of famous Nakusp restaurants such as the “Hut Drive-In” and “the Lord Minto,” of new and renovated hotels, and of the town’s beautiful waterfront walkway reflect the developing tourist economy (pp. 278-283). Eventually the development of the Nakusp municipal and Halcyon hot springs, a regional trail system, and a music festival drew even more visitors to the region. Kusch suggests that the developing tourist economy also halted the long decline of the Upper Lardeau region by the 1980s.

Our Coloured Past illustrates well how the people and communities of the region developed an interest in the past in response to the upheaval and losses of the 1960s. Local historians, photographers, and community members wrote about and photographed the “traditional” communities and settlers of the Arrow Lakes and Upper Lardeau that went back to the 1890s. They also collected artifacts including old mining and farming equipment, railway cars, and the remains of sternwheelers, and established what eventually became the Nakusp and District Museum. A focus on “pioneers” led to nice photographs of early settlers Wilfrid and Walter Jowett of Edgewood, Fred Kirk of Glenbank, Ina and Fred Lade of Beaton, and Allan and Minnie Marlow of Trout Lake (pp. 238, 251, 256, 268).

A similar focus on communities, on the other hand, led to valuable images of the earliest log cabins, schools, churches, mine buildings, and railway stations. Bruce Rohn’s photograph of Rose Rohn, Mary Koch, and Mary Warkentin at work in 1965 on the history of their doomed community, Renata, must be one of the most remarkable photographs ever taken of the writing of British Columbia history (p. 134). By the 1980s, the “traditional” past of the Arrow Lakes had come to serve the tourist industry as Nakusp welcomed visitors to “Minto country.” Our Coloured Past reveals well how the province’s building of the Keenleyside dam led to both feelings of loss and of pride in the region for the “traditional” communities and people of the Arrow Lakes.

In all of this, Kusch’s collection suggests that, by the 1940s, most Arrow Lakes settlers had largely forgotten the Indigenous people and past of the region. Our Coloured Past includes images of pictographs lost or damaged as a result of flooding (pp. 93-94). However, Kusch found only a few photographs of the reserve at Oatscott and no photographs of Indigenous people even from recent years (pp. 308-310). Our Coloured Past does not mention that the Canadian government declared the Arrow Lakes Band extinct in 1956, in the years immediately before the government negotiated the Columbia River Treaty. It does not mention any of the Indigenous nations, along with the Lakes people (the Sinixt), that lived in and made use of the region. At the same time, we know that some settlers were aware of the region’s indigenous past: H.W. “Bert” Herridge, the Member of Parliament for Kootenay West from the 1940s to the 1960s, collected material on the “Arrow Lakes Indians” to write a history, while other settlers had close relations with Indigenous people and others amassed private collections of artifacts.[3]

Our Coloured Past’s limited discussion of the region’s Indigenous past, even of a discussion of the limitations of the photographic record, is a weakness of an otherwise carefully researched, detailed, and important set of images of the Arrow Lakes and Upper Lardeau regions.

*

Duff Sutherland has taught undergraduate history courses for twenty-five years. For the past nineteen of those years, he has taught at Selkirk College at Castlegar in the West Kootenay. One of the courses he teaches is A History of the West Kootenay. As well as many book reviews in The Ormsby Review, BC Studies, and elsewhere, Duff has published articles on Newfoundland labour history and the relations between settlers and Indigenous peoples in the West Kootenay. He is currently writing about loggers and their unions in the East Kootenay during the 1920s.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Tina Loo discusses “brute force technologies” in “High Modernism, Conflict and the Nature of Change in Canada: A Look at Seeing Like a State,” the Canadian Historical Review 97, 1 (March 2006), p. 47.

[2] Hazel Stark is quoted in Loo, “High Modernism,” p. 48.

[3] Eileen Delehunty Pearkes, Geography of Memory (Nelson: Kutenai House, 2002), pp. 24, 31-35.

3 comments on “#604 BC Hydro’s destructive legacy”

One reason why I read books on local histories is that I learn that there are so many nice things in life. I was especially interested in how your district cultivated fruit. I was also interested in how the paddlewheelers and the railways worked together to bring fruits to the West Coast and to Alberta.

I would hope that the writer asserts without any trace of ambiguity that the Columbia River Treaty was not so much about cross border, bio-regional flood control but about the absolute need for the Columbia Gorge corridor to develop the biggest aluminum manufacturing industry in the US with the security of cheap electricity that the BPA (Bonneville Power Authority) could not otherwise provide.

The Grand Coulee dam was a good start but only just that.

As a Washington Post article in 1979 states, “it (aluminum production) takes an average of 16,232 kilowatt hours to turn out a ton of aluminum, compares with 77 for a ton of steel.”

And while aluminum may be one of the best recyclable metals out there, it is still an energy hog extraordinaire when it comes to producing it.

So essentially, the Arrow lakes environment was sacrificed on the alter of the US aluminum industry.

Comments are closed.