#576 In convo with Van Camp

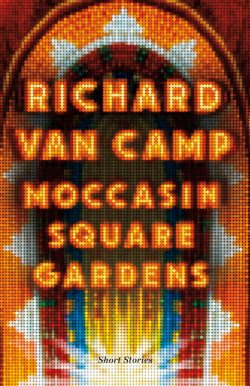

Moccasin Square Gardens: Short Stories

by Richard Van Camp

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2019

$19.95 / 9781771622165

Reviewed by Paul Falardeau

*

Richard Van Camp, the celebrated Tłįcho storyteller, may be best known for his novel, The Lesser Blessed, or his involvement with the CBC program, North of 60. However, one would be remiss to end the story there. Van Camp is a consummate storyteller of the Dene nation, in Denendeh, the land north of the 60th parallel, known by its colonial epithet “The Northwest Territories.” His stories, then, focus on these people, the Tłįcho (or “Dogrib”) living in and around the fictional Fort Simmer, his hometown of Fort Smith and the areas in orbit of these towns. In his new short-story collection, Moccasin Square Gardens, Van Camp lets the light of these people shine out, beautifully detailing their inner and outer worlds: the dirt and barriers they face alongside the love and community that have made them resilient warriors and survivors ripe with stories to tell.

Richard Van Camp, the celebrated Tłįcho storyteller, may be best known for his novel, The Lesser Blessed, or his involvement with the CBC program, North of 60. However, one would be remiss to end the story there. Van Camp is a consummate storyteller of the Dene nation, in Denendeh, the land north of the 60th parallel, known by its colonial epithet “The Northwest Territories.” His stories, then, focus on these people, the Tłįcho (or “Dogrib”) living in and around the fictional Fort Simmer, his hometown of Fort Smith and the areas in orbit of these towns. In his new short-story collection, Moccasin Square Gardens, Van Camp lets the light of these people shine out, beautifully detailing their inner and outer worlds: the dirt and barriers they face alongside the love and community that have made them resilient warriors and survivors ripe with stories to tell.

The first story in Moccasin Square Gardens opens with the lines, “I wanna tell you a beautiful story, and I’ve been waiting for someone very special to tell it to.” It’s hard not to see the meta-cue here. One of the most exciting and engaging ways that Indigenous writing has been a tool for healing is in language revitalization. Authors such as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Comic artist Cole Pauls have created works that smartly integrate Anishinaabemowin and Southern Tutchone into English perspective-text writing, obliging readers to learn words contextually and gradually increase their usage and vocabulary.

Though Van Camp does indeed dabble in this practice, Moccasin Square Gardens focuses more in revitalizing how his language was spoken than in the integration of individual words. Each story is written so that you feel it is being told to you. That is, each story has a narrator who is speaking to you as an audience. This is written, oral storytelling. There are “ahhs,””umms,” and “likes” galore. The tone is conversational, and whether we are hearing a tape recording or the gossip of aunties, we are getting the second-hand account, first-hand and with flavour.

“I need oral storytelling in my life as a listener because I’m always filtering the pauses, the slang, the rockabilly of pacing, the delivery,” Van Camp admits in an interview in Briarpatch in 2016. “When I listen to a master storyteller or someone just sharing a story, I’m studying how they’re talking and how they’re standing, and what the pitch is in their voice. I can sometimes take their techniques and put them into a story.” Going deeper, where many oral traditions assume the listener has at least some knowledge of the people, places, and events being spoken of, Van Camp’s stories are filled with places and characters from his other works, making all his work connected to a larger, deeper story universe.

Perhaps foremost of these are the two “Wheetago War” stories that anchor the book. Wheetago are a race of supernatural beings of lore whose name translates as “body eater.” They live up to their name. These are two of the most brutal pieces of speculative fiction I have ever read.

Between tearing humans in half like a bad contract and decorating their heads by jamming antlers into their skulls, we learn that the Wheetago are the real terror in the north — so move over White Walkers. Though these monsters seem more like something out of Spawn or Christophe Gans’ Silent Hill, they do share one thing with the White Walkers, the icy Game of Thrones menace: both are a not-so-subtle result of mankind’s relationship with the natural world. The narrators in these stories seem to believe that the return of the Wheetago is the direct result of the global climate crisis, with references to Site C, Muskrat Falls, and Standing Rock. Blending the paranormal with the very real horrors of our world, it’s not surprising that Van Camp has been mentioned in the same breath as authors like Stephen King. Even when there are no monsters, humans do a fine job of messing things up, be they corrupt tribal leaders, crooked gamblers, rapists, or other less than reputable agents of discord.

It’s not all aliens and sadness though. There is plenty of love and humour here. In fact, there is healing in Van Camp’s book because the darkness never outweighs or overcomes the good, the loving, or the author’s ability to crack a joke. The corrupt leader in “Super Indians” ends up getting his just desserts in perfect sitcom fashion, and “I Am Filled with a Trembling Light” ends with such a powerful bit of Medicine-fuelled revenge that you will stand up and cheer.

Ultimately, these are all stories of healing and resilience, but not all of them are so serious. “The Promise” is a story of the lasting friendship between two boys who are grounded for performing illegal wrestling moves. It revolves around the beautiful line, “I motioned that we should sit under the slide, like we always did, in the shade and the light of each other. Even in Heaven we’ll meet there, I bet.” “Man Babies,” a rant about the titular plague, becomes an exploration of its cause, with an ending that will inspire some tears too. And don’t worry about things getting too serious because Van Camp peppers you with great one-liners like, “Basically. His whole place smelled like Frog Ass.”

There are so many standouts in Moccasin Square Gardens that it hard to pick a favourite, from the dread of the Wheetago — readers new to Van Camp’s work will be excited to know that Wheetago Wars are part of a continuing narrative, with other episodes found in older collections. Now we just need a collected edition or, maybe a great on-screen adaptation — to the tearjerker “Ehtsèe/Grandpa.” Yet Van Camp has inscribed the book with a quote from his mother: “First punch has to be really good.” It rings true.

The story “Aliens” stays with you long after its heartening conclusion. It is told through the lens of an auntie gossiping with the other aunties about their niece, who agrees to go on a date with the town’s strange loner, under skies filled with the mysterious ships of the star people who have returned to Earth’s skies. The lesson of this short piece is unforgettable and beautiful, so read it twice. And then write it down. Ultimately the aliens in this story are not visitors from another world, but the old ones. They are harbingers of the return of the old world, of the good way of living and being kind to each other.

This and others stories in Moccasin Square Gardens will bring you a “soul sigh,” as Van Camp describes it. The conversational tone will keep you gobbling up the pages. This book reminds us that Van Camp is an essential voice in Canadian Indigenous literature, a vital group of writers and activists who are driving our literature and our people forward. Don’t forget to read to the end for a knock-knock joke and a beautiful little poem that crystallizes the work, a prayer for the past, and for the future that is starting right now.

*

Paul Falardeau is a poet, essayist, brewer, and most recently an English teacher living in Vancouver, a city on the unceded lands of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, to whom he offers respect and gratitude. He is a graduate of University of the Fraser Valley and Simon Fraser University. He has published in Pacific Rim Review of Books, subTerrain, and Cascadia Review, and he contributed an essay to Making Waves: Reading B.C. and Pacific Northwest Literature (Anvil Press, 2010).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#576 In convo with Van Camp”

Comments are closed.