#575 The late, great, James Teit

At the Bridge: James Teit and An Anthropology of Belonging

by Wendy Wickwire

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019

$34.95 / 9780774861526

Reviewed by Daniel Marshall

*

In my travels as an historian over the years through the communities of the southern B.C. Interior, I have heard two names repeatedly in conversations with regard to the history and cultures of Indigenous peoples. The first is the subject of this extraordinary book — James Teit (1864-1922) — a prolific ethnographer and Indigenous rights activist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second is, in fact, the author of At the Bridge: James Teit and the Anthropology of Belonging, new from UBC Press.

In my travels as an historian over the years through the communities of the southern B.C. Interior, I have heard two names repeatedly in conversations with regard to the history and cultures of Indigenous peoples. The first is the subject of this extraordinary book — James Teit (1864-1922) — a prolific ethnographer and Indigenous rights activist of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second is, in fact, the author of At the Bridge: James Teit and the Anthropology of Belonging, new from UBC Press.

Wendy Wickwire — an anthropologist and University of Victoria professor emeritus, has studied Teit for decades, and though their lives are separated by about a century of time, Wickwire’s name has become synonymous with that of Teit’s and, as her new book explores, the two B.C. writers share an “anthropology of belonging” of actual engagement with Indigenous communities as “participant observers.”

In the past, academically-trained anthropologists practiced a clinical, arms-length type of “salvage ethnography,” believing that they were witnessing the last gasps of a dying peoples. “Their goal was to ‘salvage’ information about ‘the natives’ before their disappearance,” Wickwire asserts. “It was not to advocate for their survival or oppose the forces driving their demise” (p. 25). Furthermore, Wickwire continues, “Teit’s findings challenged the popular belief that the Indians were sources of their own decline,” a contention that was simply “not supported by the evidence.” (p. 100).

Conversely, the power of Teit’s ethnographic work was a direct result of living and associating with Indigenous peoples. “His was a life close to the land and its people … ‘dwelling in its whole range,’” states Wickwire. “This was the lived foundation for his anthropology of belonging …. all of it decades ahead of its time” (p. 161).

James Teit did not flit through these Indigenous communities as a detached observer (as did his colleague Franz Boas, the “Father of American Anthropology”). Instead, he fully immersed himself in the land and its people to the point of taking an Indigenous wife, Antko, herself a member of the Nlaka’pamux (pronounced “In-kla-KAP-muh”) Nation.

I know from my own work with Coast Salish peoples that one cannot expect to make an instantaneous relationship with native elders and secure their confidence by merely breezing in for a short, scheduled appointment. “You white guys have the watches — but we have the time,” one chief used to say to me. And this is a point that Teit well understood – as, indeed, does Wickwire.

Boas, as a high intellectual, was both impatient and rather awkward in his attempts to engage with local Indigenous peoples. Teit apparently offered some advice to the German-born American who was prone to make quick in-and-out forays into native communities: put simply, “you want to take your time” (p. 123).

While Boas’s scientific goal was “for a ‘studied neutrality’ in anthropological reporting with the narrator posing as ‘an impersonal conduit’ . . . uncontaminated by personal bias, political goals, or moral judgements” (p. 16), the success of Teit’s ethnographic work, states Wickwire — the sheer detail and extent of Indigenous lifeways collected — is largely attributable to his anthropology of belonging, of being fully present and living amongst those he wrote about.

In 1907, the anthropologist John Swanton gave voice to Teit’s amazing scholarship: “As all American anthropologists are aware, Teit’s ‘Thompson River Indians’ ranks as one of the very best monographs on any single American [sic] tribe.” But as Wickwire notes, these same anthropologists “overlooked the unique style of fieldwork that underpinned it” (p. 160) and, though heavily dependent upon his exacting studies, at times they left the gifted “amateur” of Spences Bridge severely under-credited and indeed plagiarized:

Teit was an amateur, but a unique one. His field methodology had required no formal academic training (indeed, it may have suffered from it), and there was nothing ‘soujourning’ about it. The ‘field’ was his home; so-called ethnographic informants were his relatives, neighbours, and friends; and ‘participant observation’ was his daily practice (p. 160).

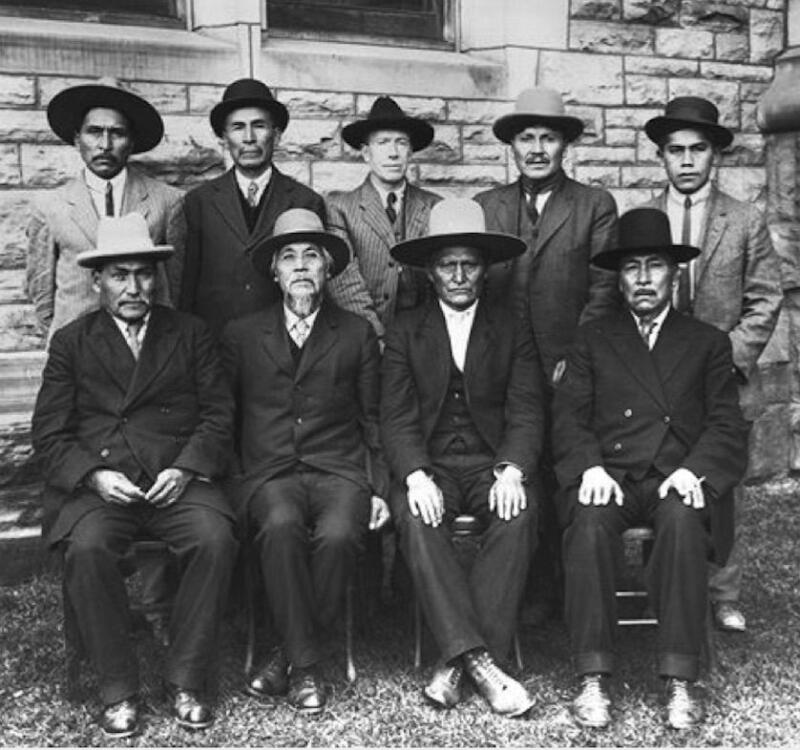

And while Teit’s later advocacy for Indigenous peoples in their fight for Native rights certainly precluded him from full acceptance in the contemporary academic world, it also illustrates the strong bonds of trust, loyalty, and confidence that he developed with B.C.’s Indigenous peoples. “Teit’s exclusion from anthropology’s pantheon of heroes,” Wickwire writes, is nevertheless “offset by his hallowed place in local Indigenous communities.”

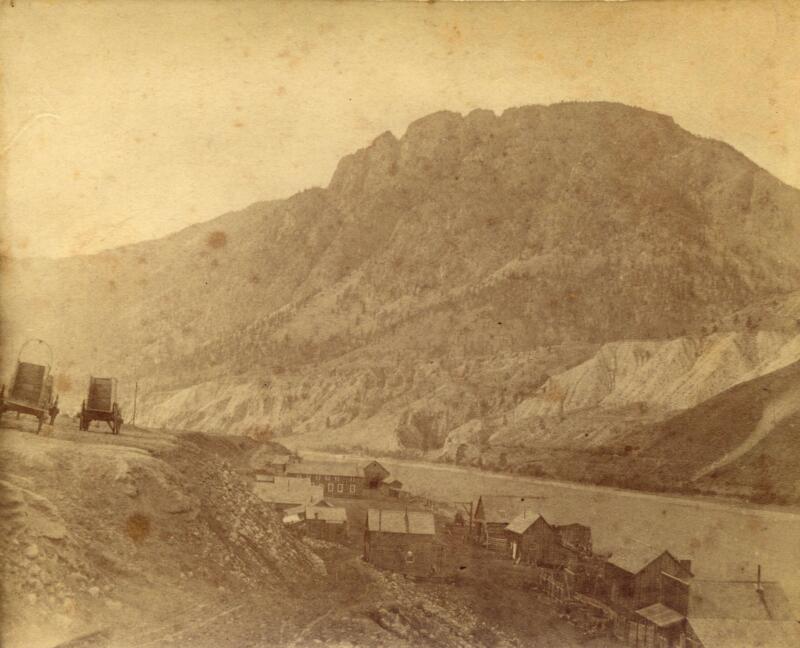

While Teit continued to record the stories and lifeways of many Indigenous peoples – such as the Nlaka’pamux (Thompson), St’at’imc (Lillooet), Secwepemc (Shuswap), Syilx (Okanagan), Schitsu’umsh (Coeur d’Alene) and Ktunaxa (Kootenay), among others — he was deeply cognizant of the atrocious impact of settler colonialism that had its start with the Fraser River gold rush of 1858. Teit’s sensitivity to recent change was considerable, as he wrote:

The sudden changes in their methods of living forced upon them by new conditions, resulted in the breaking down of almost all their laws and customs and in the loss of authority by their elders and chiefs. The removal of the old restraints undermined their power of resistance and left them with practically without protection against the evils of the white man’s civilization. They had no guidance or protection from the white men who had forced new conditions upon them, and the change of life was too abrupt and far-reaching for them to adapt themselves to it with readiness (p. 179).

Far from the arms-length refusal of the Boasian school to grapple with the changes caused by the onset of colonization, Teit saw the need and embraced the opportunity.

His activism also entered the political sphere. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Teit was one of three great non-Native allies who worked closely with and advocated for B.C.’s Indigenous communities: Reverend Charles Tate, who worked primarily with south Coast Salish peoples such as the Cowichan and Squamish; the Reverend Arthur O’Meara, who was particularly associated with the Nisgha peoples; and of course Teit, spokesman for the Interior Salish peoples.

Tate, Teit, and O’Meara were well known to each other and often worked in concert to assist all Indigenous peoples towards advancing province-wide legal strategies for the resolution of outstanding rights and title issues.

From 1909 until his death in 1922, Teit actively campaigned for no less than four different political organizations in the early “Fight for Native Rights” movement: the Indian Rights Association, the Interior Tribes of B.C., the Nishga Land Committee, and the Allied Tribes of British Columbia (p. 21). “He spent the last fifteen years of his life at the centre of an Indigenous rights campaign aimed at resolving BC’s contentious land-title issue,” notes Wickwire; and “like most ‘friends of the Indians’ at the time, [he was] quickly blacklisted and dismissed as a ‘white agitator.’”

Teit came by his activism honestly. He was born in the Shetland Islands, a region of Scotland that had also experienced the harsh impact of colonization. The plight of B.C.’s Indigenous people resonated personally. Wickwire’s prodigious research provides invaluable evidence of Teit’s association with a cultural and political movement in his own homeland that “aimed at repositioning Shetland as a unique Indigenous culture.”

Wickwire notes the parallels between the situation of Shetland Islanders and Nlaka’pamux people:

It was now clear to me that Teit, on arriving in Spences Bridge in the 1880s, had entered a geopolitical space that was strikingly familiar…. there was a common resonance, especially in the political sphere where the local Nlaka’pamux peoples, recently dispossessed of their land base, were deploying foreign concepts of land ‘rights’ and ‘title’ to assert their sovereignty. It seemed more than coincidental that, on the other side of the Atlantic, Teit’s Shetland friends and colleagues were deploying ancient Norse land rights as a way to detach themselves from Britain and reclaim their rights to their island land base (p. 63).

Surely this is one of Wickwire’s deepest and greatest insights – to frame Teit’s work within the “collective struggle of disenfranchised local peoples against imperial elites” (p. 97).

In my own work on the Fraser River gold rush of 1858, I was most thankful for Teit’s pioneering work in recording the Nlaka’pamux response to the mass invasion of foreign gold seekers. Academically-trained anthropologists in the Boasian tradition had neither the patience nor the community acceptance to record the elders’ amazing account of the Canyon War of 1858.

Teit recorded how Chief Shigh-pentlam (pronounced “Sha-PEENT-lum,” but also spelt Cexpē’ntlEm, and anglicized as Spintlum) at the height of the 1858 War advocated for peace, but with the firm assertion of his nation’s vast traditional lands centred at Camchin (Kumsheen), or today’s Lytton. According to Teit:

Chief Cexpē’ntlEm, in talking to the whites (in 1858) told them they had entered his house and were now his guests. He asked them to treat his children as brothers, and they would share the same fire. He did not know that they would afterwards treat his people as strangers and inferiors, and steal their land and food from them. Had he known it, there would have been [further] war, and the land would have been red with blood …. [He further said that] I know no white man’s boundaries or posts. If the whites have put up posts and divided my country, I do not recognize them. They have not consulted me. They have broken my house without my consent (p. 193).

How extraordinary that today — over 160 years later — the issue of Indigenous consultation and consent recorded by Teit remains at the very forefront of both provincial and federal politics.

On the issue of Indigenous consultation alone, Teit quite correctly saw a problem that would only continue to grow if not remedied with a fair and just solution. And Wickwire, in many ways, has continued Teit’s struggle with this immensely engaging depiction of a singular individual who sought to bring justice to a colonized people. It is, in fact, her own personal journey — infused with Teit’s sense of belonging — of which “This book is but a beginning” (p. 285).

And yet, close to a century after his death, laments Wickwire, Teit “has yet to be acknowledged within the discipline of anthropology for his pioneering achievements” (p. 284). The same could be said for his work as an historian recording vital events in 19th century B.C. history. Wickwire has done B.C. scholars and Indigenous peoples an essential service in deftly peeling back the layers of personality, family, and life circumstances of one of Canada’s unsung heroes.

Wickwire’s work is not only highly recommended, but a definite must-read for anyone concerned with the unresolved Indigenous “land question” that continues to haunt the province to this day.

*

Editor’s note: see here for an interview about James Teit between Wendy Wickwire and Mary Blance (the Shelagh Rogers of Shetland) on BBC Shetland. The interview with Wendy starts at approximately 15:40 minutes into this broadcast.

*

Daniel P. Marshall was educated at the universities of Victoria and British Columbia, where he received his Ph.D. in 2000. He is author of Those Who Fell from the Sky: A History of the Cowichan Peoples (Cowichan Tribes, 1999, reprinted in 2007). Dan was host and historical consultant for the documentary Canyon War: The Untold Story (2009), televised on the Knowledge Network, APTN, and PBS, which took honours at both the New York International Independent Film and Video Festival and Worldfest 2010 (the Houston International Film Festival). In 2015, Dan acted as Chief Curator for the Royal B.C. Museum’s “Gold Rush: El Dorado in British Columbia” exhibit. His book Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New Eldorado (Ronsdale Press, 2018), has won three awards: the Basil Stuart-Stubbs Prize for Outstanding Scholarly Book on British Columbia; the Canadian Historical Association’s Clio Award for the most exceptional contribution to B.C. history; and the Gold Medal (Best Regional Non-Fiction) of the “Ippy” — Independent Publisher Book Awards. all for books published in 2018. Daniel Marshall lives in Victoria.

*

The British Columbia Review

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

Formerly The Ormsby Review, The British Columbia Review is an on-line journal service for BC writers and readers. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Provincial Government Patron (since September 2018): Creative BC. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

2 comments on “#575 The late, great, James Teit”

Wendy Wickwire’s book has been highly recommended to me by the chief of the Okanagan Indian Band. I will be purchasing it and reading it. Thank-you for this review by Daniel Marshall!

Thanks Daniel for a great review of what appears to be a great book. I’m really looking forward to reading it now.

A couple of things. First, Franz Boas was thoroughly German and a “lapsed” Jew who never “became” an American until the age of 30. He was put in touch with the possibilities of anthropological investigations of Indigenous people through the Jacobsen brothers, those Norwegian adventurers also associated with the Museum für Völkerkunde or Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin. In the mid-1880’s, Johan Adrian Jacobsen, a Norwegian ethnologist and adventurer working for Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde, was engaged by them to gather ethnographic and other specimens on the west coast of North America. For the next two years, he travelled through British Columbia, Yukon, and Alaska.

In 1885, Jacobsen was back in British Columbia, Canada, where he and his brother Bernard Filip Jacobsen hired a group of nine Nuxalk (Bella Coola). He brought them back to Europe and travelled with them until 1887: see three Nuxalt Legends, Bernard Filip Jacobsen, Northwest Anthropology, https://www.northwestanthropology.com/

Of course, Filip Jacobsen didn’t just drain the Kwakiutl but the Coast Salish as well. As Marianne Nicholson says in the A River of Wealth: How Kwakwaka’wakw Art Flowed Across the Continents, an essay accompanying the “The Power of Giving” exhibition catalogue, “What started as a trickle soon became a deluge and, from 1880 to 1915, the halls of the Ethnographic Museum in Berlin, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the Chicago Field Museum- amongst others- became flooded with art from the Pacific Northwest Coast.”

Another statement you make also needs some clarification. You say, “During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Teit was one of three great non-Native allies who worked closely with and advocated for B.C.’s Indigenous communities: Reverend Charles Tate, who worked primarily with south Coast Salish peoples such as the Cowichan and Squamish; the Reverend Arthur O’Meara, who was particularly associated with the Nisgha peoples; and of course Teit, spokesman for the Interior Salish peoples.”

A fourth really needs some acknowledgement and that is another Scot, James Halbold Christie. This man was an accomplished explorer that settled in Lumby in 1892 and married a Metis lady, Amelia Duteau. He also became a fierce champion for native rights for the Okanagan acting as the Secretary/Treasurer for the Okanagan Defence League in their disputes with the corrupt Indian Agents such as Kummisky, etc. He was harassed and bullied, but the big Scot was not easily put off even when hauled in to the Vernon gaol on the pretext that he might be Bill Miner, the Kentucky criminal who some have lionized for his train robberies. Miner was 5’ 8” and had a southern drawl. Christie was 6’ 3” and had a Scottish brogue. Jim was a policeman and pal of Sam Steele, leader of the Olympic Mountain Times Expedition in the Apple state and one of 20 soldiers to greet Chief Sitting Bull and usher him across the Medicine Line after the Battle of Little Big Horn. His working class background and the fact that he did not publish any works (but wrote many, many letters to Ottawa and Victoria!) has relegated him to languish in relative obscurity. It has been said that the revisions to the Indian Act in 1927 were aimed at O’Meara and Christie (Duane Thompson).

I am currently writing a story of jim Christie. It will clearly demonstrate that, like Teit, there were white that were not part of the colonial settler groupthink and that they valued the outlook and lifestyles of the Indigenous.

Comments are closed.