#573 BC’s forgotten artists

The Ormsby Review presents a joint review of all ten books in the Unheralded Artists of B.C. Series from Mother Tongue Publishing of Salt Spring Island, 2008-2017. — Ed.

- Monika Ullmann, with an introduction by Brooks Joyner, The Life and Art of David Marshall (Mother Tongue: 2008) (UABC #1)

- Eve Lazarus, Claudia Cornwall, and Wendy Newbold Patterson, with an introduction by Max Wyman, The Life and Art of Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman, & LeRoy Jensen (Mother Tongue: 2009) (UABC #2)

- Mona Fertig, with an introduction by Peter Such, The Life And Art of George Fertig (Mother Tongue: 2010) (UABC #3)

- Sheryl Salloum, with a foreword by Sherrill Grace, The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton (Mother Tongue: 2011) (UABC #4)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Pat Martin Bates, The Life and Art of Ina D.D. Uhthoff (Mother Tongue: 2012) (UABC #5)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Kerry Mason, The Life and Art of Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (Mother Tongue: 2013) (UABC #6)

- Adrienne Brown, with an introduction by Robert R. Reid, The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb (Mother Tongue: 2014) (UABC #7)

- Peter Busby, with an introduction by Paul Wolf, The Life and Art of Jack Akroyd (Mother Tongue: 2015) (UABC #8)

- Christina Johnson-Dean, with an introduction by Robert Held, The Life and Art of Mary Filer (Mother Tongue: 2016) (UABC #9)

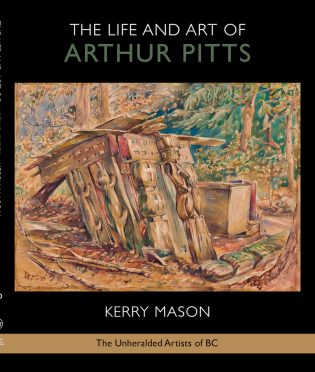

- Kerry Mason, with a foreword by Daniel Francis, The Life and Art of Arthur Pitts (Mother Tongue: 2017) (UABC #10)

All books reviewed by Nellie Lamb.

*

*

Many people dedicate their working lives to making art. Very few financially support themselves with that labour. Even fewer become household names. Statistics indicate that in Canada the average annual income for a visual artist was roughly half of that of a worker in the overall labour force. In 2010 sixty percent of artists made less than $20,000 and fifteen percent of artists operated on a financial loss. [1] I don’t have statistics for how many artists work in obscurity but it’s safe to say most do. Some artists struggle against these realities while others embrace living in the margins and even believe it is necessary to their art. One such artist, painter Jack Akroyd, wrote in a card to friends “An artist should be poor!!!!!!!” But is the financial inequity between most artists and the average worker fair? Is the work of the few artists who are widely shown and written about superior to that of the artists to those who remain in the margins of art history? What effect does the inequity of the art world have on artists? And how should we write about artists who haven’t been written about before?

The Unheralded Artists of BC, a series of ten books published between 2008 and 2017 by Mother Tongue Publishing, introduces fourteen British Columbian artists who until now have been left out of the art historical canon. The series began with owner/operator of Mother Tongue Press, Mona Fertig’s childhood memories of her father, George Fertig, a Vancouver painter interested in mysticism and Jungian psychology. Fertig became frustrated with much of the art world and felt he never received the critical acclaim or financial security he was due.

After George’s death in 1983, Mona decided to bring his work the attention it had not received during his life. The process of researching and writing about her father’s work lead her to other artists whose stories are lost to a collective “historical amnesia.” These artists became the subjects of the Unheralded Artists of BC series: David Marshall, Leroy Jensen, Frank Molnar, Mildred Valley Thorton, Leroy Jensen, Ina D.D. Unthoff, Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, Jack Akroyd, Jack Hardman, Harry and Jessie Webb, Mary Filer, and Arthur Pitts. None had been substantially written about before. The series’ central concern is that these artists and their work deserve to be remembered. In these detailed and well-illustrated biographies, Fertig and the series’ authors try to right this perceived wrong.

Despite being an art historian, curator, art educator, and the child of artists I still don’t know how we should measure an artist’s success. Measuring it in an artist’s commitment to their work is, I suspect, an inclusive way to start; to be able to continue to make art in the face of obscurity and poverty is a significant achievement. We might also consider insight, imagination, originality, and influence on other artists. It might be that there is no single rubric for art. However, I can say unreservedly: the primary measurements of an artist’s achievements are not popularity and sales.

The Unheralded Artists series emerges from a similar perspective and suggests that devoted artists deserve attention whether or not they are able to sell or exhibit their work widely. As Sherrill Grace writes in the foreword to The Life and Art of Mildred Valley Thornton, “For every great modern artist… there are hundreds of artists who play minor roles, but who are essential to the development of the art form…” The Unheralded Artists series begins to fill in the spaces between the well-known characters of B.C.’s art history like Jack Shadbolt, BC Binning, Fred Varley, and Emily Carr and contributes to a richer body of art historical knowledge. The series adds names and details and reminds us of the breadth of artistic practice all around us. One need not travel to far away places to come into contact with serious art.

As the child of two relatively unknown artists, I am sympathetic to Fertig’s goal. I am also thankful for her work as a publisher; my introduction to Mother Tongue Press was through Claudia Cornwall’s At the World’s Edge: Curt Lang’s Vancouver, which presents Lang’s biography as a parallel to the history of Vancouver through the second half of the 20th century. I have written about Vancouver’s art of the sixties and agree with Fertig’s assertion that “there is little documented evidence of the wealth of creativity that existed before the 1970s.”

Though Vancouver is not a culture capital like New York, London, or Paris, the seventies and eighties put Vancouver on the map of cities with notable arts cultures. I believe that this expansion of artistic culture depended on the artists who were working in Vancouver in the fifties and sixties, then a provincial backwater. I believe there are too many artists whose work has gone unappreciated, and when I learned about The Unheralded Artists of BC series I found it heartening to know Fertig and the authors of the Unheralded Artists series were working to bring more of B.C.’s art history to the public’s attention.

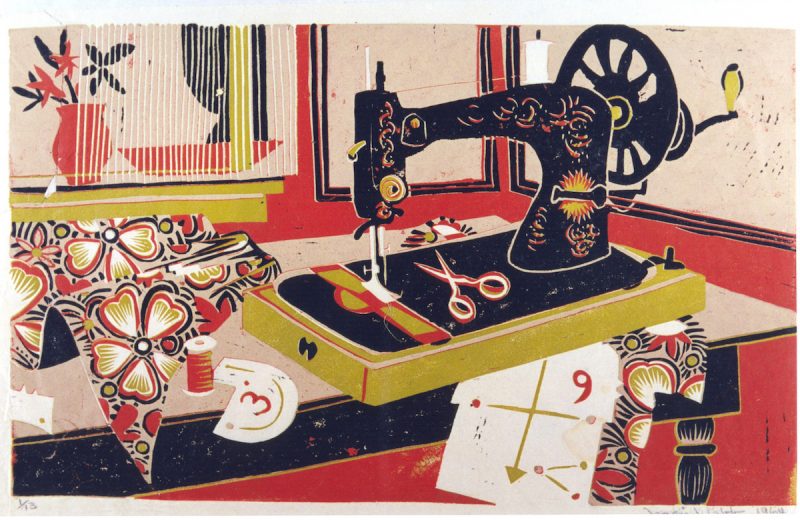

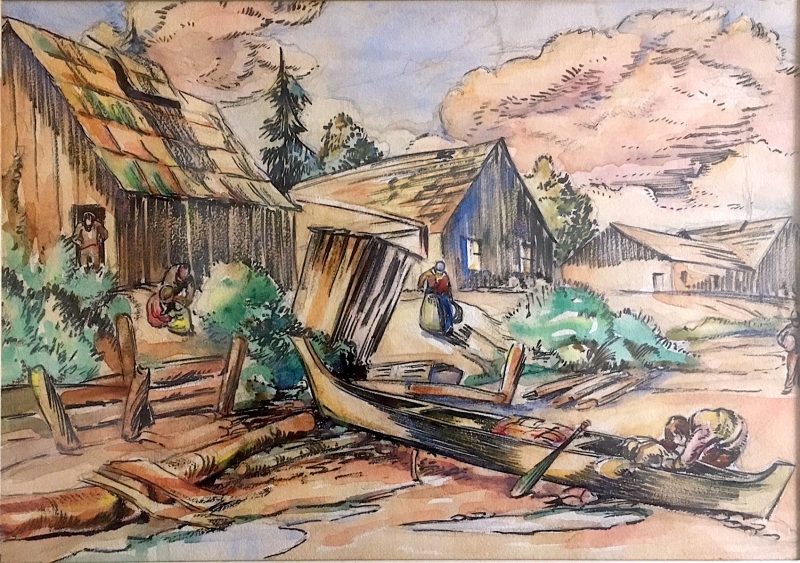

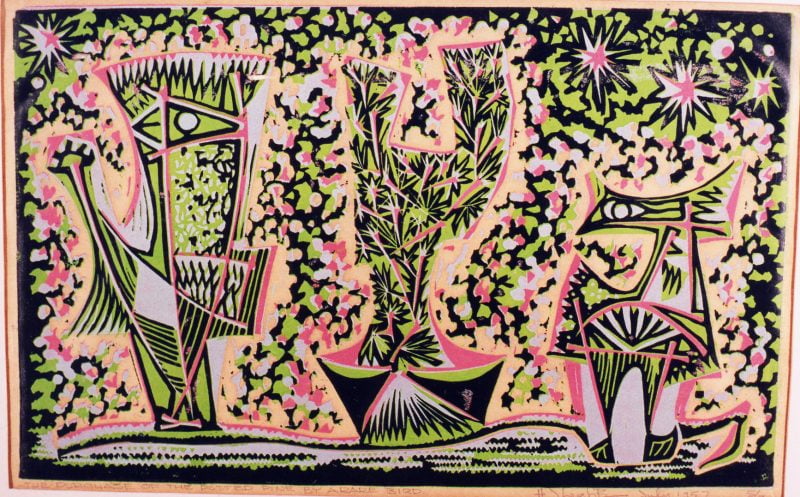

In addition to detailed accounts of the artists’ lives, the Unheralded Artists series brings high-quality reproductions of the artists’ work to the public. Each book has nearly 100 colour reproductions of artworks and photographs from the artists’ personal archives. Fertig’s instinct to feature illustrations paid off; there is a wealth of information available to readers through the images.

Several books in the series connect the excellent reproductions of the artist’s work with their biography. The work of artists like Jack Akroyd, George Fertig, Jack Hardman, and LeRoy Jensen lends itself well to biography because it is introspective and sometimes biographical itself. This is most true in the case of Akroyd’s paintings, which author Peter Busby shows are often diaristic and arranged symbolically to communicate Akroyd’s emotions. Mona Fertig connects the symbols of moon and sea in her father’s paintings to his intellectual interests in Jungian psychology, which she further ties into his personality and life story. Wendy Newbold Patterson allows the art objects to inform her biography of LeRoy Jensen and clearly articulates his artistic concerns of movement, luminosity, rhythm, and spirit.

The most successful book in the series in this regard is The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb, by Adrienne Brown. Brown is Harry and Jessie’s daughter and perhaps it is her familiarity that allows her to integrate descriptions and interpretations of her parents’ art into their biography from the outset. The Life and Art of Harry and Jessie Webb is engaging and makes the case for more attention for Harry and Jessie’s work, not by lamenting their lack of attention or unfurling every detail of their lives but by tying together their biographies, the themes in their work, their concerns, and their techniques so that a full picture emerges of the artists and the milieu in which they worked.

Despite the successes of some of the books, the series falls flat. Instead of making a significant addition to art history, the series fails to answer the question implied in its basic premise: what makes an artist “unheralded?” The qualifications to be in this group seem to be that no book has ever been devoted to the artist and that the artist worked primarily in B.C. in the 20th century. But that includes most artists who have ever worked in B.C. Why group these fourteen artists and not others? The qualifications for being an Unheralded Artist are never laid out, which leaves the series shallow. My guess is that these were the artists on Fertig’s radar. Just like the curators who are implicated by several authors in the series for failing to include David Marshall or Mildred Valley Thornton in their exhibitions, Fertig only had so much space in the series and chose artists who were visible to her and who she thought deserved the attention.

We need artists’ biographies to reflect both the artist and their time and the contemporary concerns of our time. In the individual books, the most glaring misunderstanding of contemporary thought appears in The Life and Art of David Marshall, in which author Monika Ullmann suggests that modernist styles are “timeless” by way of criticism of curators who by the 1960s were no longer interested in showcasing Marshall’s large modernist sculptures. This assertion is incorrect — artistic styles are always rooted in a specific socio-political time. In Marshall’s case, Ullmann misses an opportunity to link Marshall’s old-fashioned personality and “traditional” values to his artistic choices in a meaningful way.

Overall, the series doesn’t take an accurate reading of contemporary understanding of who is left out of artistic discourse both historically and today. There isn’t one artist of colour in the series though there are several artists who took Indigenous people and people of colour as their primary subjects. I am wary of tokenism but in almost any survey of artists published in the 21st century and especially a survey of lesser-known artists I expect to find stories of people of colour, people with disabilities, and LGBT2SQ+ people since these are the voices that have so often been harshly excluded from the art world (as well as many other parts of society).

If it was hard for Mother Tongue’s white men and women artists to fit into the art world, it was harder and even dangerous for many others. I imagine readers will be quick to point out that the series is evenly divided between women and men. It is, and the women’s stories were likely more difficult to research than their male counterparts; but any feminism that doesn’t include LGBT2SQ+ people, people of colour, people with disabilities, and other frequently marginalized voices is only ever masquerading as the real thing. Though I acknowledge that it is the nature of underrepresented stories to be more difficult to research and write, I cannot excuse any survey of “unheralded” artists of BC that does not include these stories.

Although the series fails to address systemic reasons an artist might be excluded and remain obscure (sexism, racism, classism, etc.), it reveals that the art world is often a cruel and traumatic place for artists no matter their social status. The pressure to continue showing, selling, and constantly advancing the style and content of one’s work to fit the fashion of the day wears on artists. For example, Monika Ullmann describes David Marshall’s lifelong defensiveness of his style of modernist sculpture, which had lost its popularity near the beginning of his career as an artist. Adrienne Brown writes that though her mother continued painting into her sixties, she increasingly avoided selling her paintings for fear of being taken advantage of. Even when an artist receives recognition and gets a show, it can be terrifying and wounding to share the work with critics, curators, and admirers who may misinterpret and misrepresent. In Jessie Webb’s case, this trepidation meant remaining “unheralded.”

Although these books bring the artists’ names, biographical details, and high-quality images of their work to the public they do little to convince me that these artists deserve careful attention, which is an unfortunate disservice to the artists. These books don’t make much of an argument either as stand-alone books or a series. They suggest that the art world should be more inclusive but they don’t really set a great example of inclusivity. They are against and outside the art world and yet their raison d’être is to include these artists in the art world. They begin to say something about the hardship of being an artist but it’s not thoroughly examined throughout the series and falls flat. The lack of an argument suggests that there really isn’t much to say about these artists other than to deliver a chronology about where they travelled, whom they married, and what jobs they took. After spending time with these books and looking at the images they hold, I believe much of the Unheralded Artists’ work deserves further research.

The inequity between most artists and the few who find recognition and financial security is heartbreaking. It doesn’t take much time in the art world to hear an artist — faced with playing the system or another rejection — say, “Maybe I’ll just give up on art.” Fertig’s attempt to address this failure of the art world is admirable. However, these books, like their subjects, are often out of touch with current concerns. The thorough biographical details and full-colour plates provide a valuable resource to someone who might want to take on a thorough art historical or curatorial project. A critical examination of these artists’ work remains an incomplete project. I hope it is a project some researcher will take up soon because there are many artists, both living and dead, several of whom are included in The Unheralded Artists of BC series, whose insight, ideas, expressions and contributions to art deserve thoughtful, critical attention and to be shared widely with art appreciators in B.C. and beyond.

*

Nellie Lamb is a curator and educator based in Coast Salish territory (Vancouver and Victoria). Her research and curatorial practice are centred in notions of place; she is currently investigating human relationships to the sea in the context of the ecological crisis. Her educational practice is also place-based and focuses on the value of practicing deep observation. Nellie graduated with a Masters of Arts from the University of Victoria’s Art History and Visual Studies program in 2018. She has curated exhibits for Integrate Arts Festival’s FUSE, the University of Victoria’s Legacy Art Galleries, and Open Space.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Kelly Hill. A Statistical Profile of Artists and Cultural Workers in Canada Based on the 2011 National Household Survey and the Labour Force Survey. Hamilton Ontario: Hill Strategies Research Inc. 2014. Accessed January 4 2019

26 comments on “#573 BC’s forgotten artists”

Wow — what a lot of deep thinkers! I’m nowhere near you folks in my level of intellectual critique, etc., but I do collect historic paintings by Canadian artists and I think this is a great series of books: really interesting to read, beautifully produced, full of excellent colour pictures, and reasonably priced. Where else could someone like me find rare works such as these outside of hit or miss searches on the Web? Now I have a whole new list of artists to seek representative examples of for my collection. As much as I love the work of Binning and the early Jack Shadbolt, they are very rare, expensive and highly sought after in comparison.

Nellie Lamb’s profoundly annoying review has done one thing: it has brought renewed attention to these ten artists. Kudos to Mother Tongue for this important publishing venture.

“We need artists’ biographies to reflect both the artist and their time and the contemporary concerns of our time?” Nellie Lamb appears to have a list of what those are. Her comments would have benefitted by revealing it. Without that, she has failed to initiate the engagement she appears to be asking for. Her latent list does appear to include a definition of inclusivity of a particular kind, as well as a certain level of market success, as “contemporary concerns.” She also appears to work from the assumption that “the art world” is the world of galleries, and other forms of organized display set within what many British Columbians view to be elite social structures. Clarity would have helped.

A few comments in the face of the lack of clarity. First, “contemporary concerns” vary widely, both within Canada and around the world. Defining one set of concerns as “contemporary” suggests that there are other sets, currently in practice, that are not. I would think it would be more inclusive to note that they are all contemporary, whatever they are, even ones that are socially unwelcome. I would argue, for example, that the politically-charged neo-Nazi graffiti of Dresden is profound art, as is its context in street battles with Communists, Anarchists and Anti-Fascists. I would argue, for example, that the shop windows of Reykjavik are art.

I’ll go with my friend, the East German dissident playwright and direct heir to Bertolt Brecht, on this one. He said that he would go anywhere, and write about anything, if he found creativity there, even among the violent criminal class, because under Stalinism and its official art he knew what the opposite did to humans. He chose exile in order to have the freedom and space to write more openly about socialist reforms.

It might be (we don’t know) that those are not “contemporary concerns” in Nelly Lamb’s conception, or that his work is not “art” in her conception, because it is stage work and book work and is not concerned with the kind of objects and installations that take place in specialized spaces called art galleries, or in temporary spaces in streets, and so on. I just don’t know.

I do know that as Brecht’s heir his socialist credentials are better than mine or Lamb’s. Without having received any clarity from the review, I am left with the impression that to Lamb there are different classes of social activity, some are what is called “contemporary” and that (to Lamb) the value of the art of the past is to be illuminated by a “contemporary”light to embed it within that list of “contemporary” concerns.

That is, surely, a gestalt of several arguable points. Kapuscinski, after all, took Herodotus on him for two decades of journalism through twenty-five Third World revolutions, and with that anchor, the oldest book in the journalistic tradition, produced the greatest journalism of the twentieth century, and great social art. He is dead, and so not contemporary, and did not produce the kind of art shown in galleries.

I suspect this excludes him from Lamb’s discussion, but without clarification as to why, precisely, she appears to have limited her scope as she has to a narrow slice of what art-making or inclusion are, I run the danger as a reader of assuming that she is talking to a closed group of experts, perhaps even one that sees its role in the public as judging value.

That would be a shame. We’re humans. We’re uncontrollable apes, at times lovable and at times the most vicious predator of all. We rarely agree on anything. Judgement is not the only possible response to this difficulty and, given that infinitely variable humans are involved in life today, is not the only “contemporary” one. I’m old enough to have seen “contemporary” change four times now, at least. It’s an elusive beast. There are, however, opportunities for opening. I hear the desire for it in all the comments here and in Lamb’s review. Such a great commonality!

I am saddened that there appear to be closings as well. I look forward to hearing that they are not closings, only omissions. Here at the end of a civilization and the troubling birth of a new one, I believe we need to be carrying as much treasure forward as we can, whatever we can gather and carry, whatever we think might be of value and might help the kids. Mona Fertig has taken on that task admirably.

Lamb appears to be telling us that it is not enough. Of course it isn’t. All of us are trying to carry what we can. I’m not convinced that sorting is necessary or helpful. Celebration, I think, is a hard enough goal to attain, but one that is just within our apish grasp.

After reading all these articulate comments, which seriously overshadow the review that triggered them, I could almost feel sorry for would-be critic Nellie Lamb. She ventured out of her obscurity with a volunteer review, no doubt hoping to make a bit of a mark by pronouncing the Unheralded Artists series “shallow,” and here she finds herself so roundly denounced by such a who’s who of BC cultural commentators she must feel like finding a deep cave to crawl into. Hopefully this will be a learning experience for her. As many have noted, Lamb’s reasoning is muddled, but even if it were razor-sharp it would raise a fatal question about her judgment because Mona Fertig’s Unheralded BC Artists series is one of the heroic acts of BC publishing, unprecedented in the small press world. Even if the texts were utter garble, which is far from the case, the reproductions alone would justify the project by the light they cast on these unfairly forgotten careers. It is notable, as has been mentioned, that Lamb has almost nothing to say about the actual subject of the books, namely the art they contain. Sure, there are many more volumes that could have been added to the series if Mona were an oil heiress, or even if she were able to fully access regular cultural funding. But she did manage to illuminate fourteen very impressive careers most readers would never have otherwise known about, and for that she deserves unqualified praise.

I once had a reviewer say about Bozuk, my Turkish novel, that it was “brilliantly written” but as she had no knowledge of Turkish culture, it didn’t interest her. What kind of a review is that? Lamb stinks of the same hybrid fish, bottom-feeding jabberwockies. It is badly written and ill-intended, shedding light on the feeding frenzy that art has become, critics mired in jargon and limited constituencies. Mother Tongue deserves credit for finding a niche crack in the broad cavas and jumping in to explore.

“Creative acts originate, in fact, not from a knowledge of their laws, but from an incomprehensible and obscure power that is not fortified by being explained.”–Marcel Proust

For those readers unfamiliar with the Unheralded Artists of BC series and confused by Lamb’s contradictory and repetitious review, hopefully you will search out one of these beautifully designed books in Mother Tongue’s well-researched series, illustrating and illuminating the lives and art of 13 previously undocumented British Columbia artists, “driven by their daimon.” Or maybe you will stumble upon their art in someone’s home, or in a garage sale, as a friend recently did, and another door will open on their creative lives.

Between 1900 and 1960, there were at least 16,000 artists working in the province. This has been documented by art researcher Gary Sim. Most of these artists have disappeared into the folds of time, leaving only their names behind in exhibition catalogues, on the backs of paintings or lying unaccessioned in a gallery basement for a future art sleuth to discover.

The Unheralded Artists of BC series was my raison d’être for many years. It was an extraordinary time of unforgettable art sleuthing adventures, working with fine hard-working professional writers, artists’ friends and families who shared stories, collectors, photographers, designers, editors, copyeditors, indexers, researchers, mentors, art historians and art librarians. There were also exhibitions and book launches at the Burnaby Art Gallery, West Vancouver Museum, Salt Spring’s Mahon Hall, Westbridge Art Gallery, Petley Jones Gallery, the Ferry Building Gallery, the Architectural Institute of BC, the Bellevue Gallery, the Elliott Louis Gallery, the David Marshall Sculpture Gallery in Bellingham, the Victoria College of Art and others.

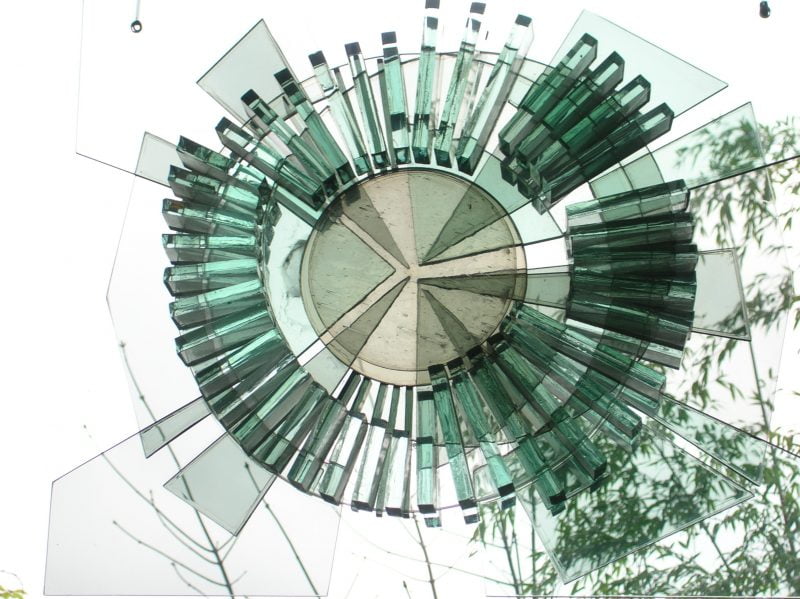

The last book in the series, #10, was published in 2017. The vision for the series was generous, but the work was labour-intensive and greatly underfunded. There is only so much light a small literary and art publishing company can heroically shine on regional and historical artists, we are proud of all our inclusions: Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher, who we brought out from under the shadow of Emily Carr; Mary Filer, the pioneer in cold-glass sculpture in Canada; Jack Akroyd with his unique and authentic visual diaries beloved by the Japanese; Frank Molnar, Jack Hardman and LeRoy Jenson, noteworthy and forgotten Vancouver 1960s rebel artists; David Marshall, the skilled and brilliant sculptor; my father, George Fertig, ahead of his time; Ina D.D. Uhthoff, single mother, founder of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and the Victoria School of Art; Harry and Jessie Webb, married artists; and Mildred Valley Thornton and Arthur Pitts, painters whose art is still valued among Indigenous elders and youth. This has been an important journey for all. Over the years, hundreds of “living” artists wrote, phoned or emailed me about being included in the UABC series, but my mandate was about unearthing the buried treasures of regional art history.

So, it is interesting that, even after all this time, cultural gatekeepers like this reviewer have continued to exclude and devalue these artists. The Vancouver Art Gallery bookstore no longer carries the series because “it doesn’t do anything for us.” Public galleries (except for the Burnaby Art Gallery, which has given exceptional and generous support to the series) are not interested in a group exhibition, a public series talk/discussion, or a book event because these artists are “not part of the current conversation.” When Knowledge Network was approached about the series as a documentary, I was told there would be no interest because “the artists are dead.” BC art history, unless it is about Emily Carr or the Vancouver School of photoconceptualism, is not taught in our educational institutions. All these exclusionary motions are about power and career. The commodity of art, and the culture it feeds, still rules. The New Orthodoxy rules.

An eternal thank-you to my family and friends for their years of support (cheerleading, bookselling, reading manuscripts, helping with events, researching, meeting artists, pouring wine…). And to all my amazing writers and all the people who have bought books and art, supported UABC fundraising, presented clues, given interviews, sent letters and gifts, attended readings, invited my authors to festivals and special events, offered encouragement and celebrated with us. These have been the best years. We made the impossible possible. Keep storming the gates.

A few words of praise for the series.

http://www.mothertonguepublishing.com/uabc-praise/praise-for-uabc-series.html

The Unheralded Artists of BC series, #1=#10, can be ordered online or from any BC bookseller.

Thank you for referencing my BC ARTISTS project, Mona. Of the more than 19,000 visual artists of BC that I’ve listed, I’d say 3,000 artists exhibited prior to 1950, perhaps 6,000 by the 1960s, and the rest have been active from then until the present day.

I understand where Nellie Lamb is coming from, and many of the previous comments speak to it. The role of the contemporary critic in evaluating works of art is not only about relating them to history and contemporary culture, but is also about providing the basis for evaluating them in terms of market value. In large part it is about assigning not just cultural value but comparative value: “This is better than that.”

In this exercise it becomes necessary to distance the art you are advancing from the mass of artistic material: to proclaim it as true art in a morass of presumably untrue art. It’s an exercise designed to enable dealers, collectors, and auctioneers — the art market — to assign price. Like it or not, this is the function of critiques like Lamb’s.

The downside, of course, is limiting yourself to a very narrow band of both input and output. You are speaking about a very limited number of artists, and a tiny audience. So instead of bringing art and people together it is actually about keeping them apart.

So there is no point in taking Ms. Lamb on. She is perfectly correct in her assessment from a marketing point of view.

Her commentary, nonetheless, raises the question of why one, even a committed market-art critic, would dismiss an entire project involving scores of professional writers, artists, and designers when there are so many ways to evaluate works of interpretation. What the exercise demands most of all is imagination.

As a writer you are free to bring whatever you want to the project. But if you have nothing constructive to say, and you dislike the subject matter — that becomes a challenge in itself. Some writers go looking for ways to approach it, to educate themselves with background research. With none of that on view in Lamb`s piece, it becomes very hard to come up with a reason for the article other than tending barriers or gatekeeping.

Personally, as a writer with art history degrees, I take exception to the lack of professionalism on the writer’s part, and I do so in solidarity with all individuals who would dare involve themselves in a public discussion of art without the permission of the Academy. In Ms. Lamb’s Art World, I sense there is no room for “other”. I’ve been there and done that, and it is hard to breathe where Lamb hangs out. What I find most affecting about her piece is the lack of interest in the work she is writing about.

Finally, I can`t help asking why any historian would not recognize that the publications in this series represent, at the very least, a wealth of research material on a group of artists working at the edge of a community which is very well known to Canadian art history. The artists profiled may not be worthy of monographs, or even inclusion in general histories, but that does not mean they are unworthy of documentation or being written into the record. To me, these ten books are a wonderful and significant contribution to the history of Canadian creators and the communities that have supported them, and continue to support them. As the Applebaum-Hébert Committee documented in 1982, the largest contribution to the arts in Canada is not from directors, curators, publishers, or editors — but from the creators themselves.

So I would like to congratulate Mona Fertig for these books on the lives of unheralded BC artists, and commend her for her vision and public spirit. The work these individuals produced and the lives they lived actually do matter. The books Mona has produced will be read and valued for a very long time — in part because no one else is paying attention. I very much hope she is recognized properly for this work.

Very well written and honest review.

Thank you ms Lamb.

Pointing out a lack of diverse representation in such a work is *always* a reasonable critique.

Many commenters here seem to be mistaking that criticism as a call to obliterate all white-person-produced art, along with the artists themselves.

A fresh read should put those fears gently to rest.

It isn’t “a” work. It’s 10 books, commissioned by a publisher to document artists who might otherwise have remained relatively unknown. I don’t think any of those commenting see Nellie Lamb’s review as “a call to obliterate all white-person-produced art, along with the artists themselves” but, rather, a piece of writing that asks the artists, their biographical details, and their artistic practice to be other than what they were. Other books looking at other artists might well find other concerns worth investigating. And this series of books does not preclude that possibility if other publishers and other critics choose to do that.

This review is a valid critique. I can see it’s an unpopular one, at least in this comments section, but Lamb’s questions of representation and acknowledgement for a wider diversity of artists are core to what seems to underlie the premise of the book series in the first place – to be unheralded, to be excluded, to question the way that success is afforded to few and withheld from the many. I can’t say the artworld is always a kind place, but I can say that what I know makes it much better (and more critical, and more rigorous, and more innovative) is the ability to question and make space for subjectivities and ideas that have been traditionally unrecognized. I can see there’s many years of experience embedded in these comments, and I can also see the author speaking from her own informed position. That deserves consideration and respect.

So, does Lamb think these books should be suppressed because of what they did not set out to do? Makes me worry now about databases like Aware and Clara and projects like Canadian Women Artists History. Who should be culled from those we were not aware of? Curious that Lamb has insight, too, into the intimate sexual practices and detailed racial and cultural backgrounds of the artists who are in this series. The lack of coherent argument is what makes this piece noteworthy. Did anybody read it ahead of time and try to figure out the overall aim or validity of the scattershot? I am sorry if my response adds to what might be seen as ‘useful’ engagement. I am writing only because I am grateful to all those, like Fertig, who engage in the difficult work of making the invisible visible so it can become part of our overall cultural nourishment.

It is strange indeed to state that “artistic styles are always rooted in a specific socio-political time . . .” Vincent van Gogh and Emily Carr would surely have appreciated a comment like that, in times when their interpretative styles were seen as having no artistic merit.The early Picasso—who painted so beautifully for years in the style of an earlier century, before evolving to the more familiar style(s) associated with his work—was alternately behind, and then far in advance, in artistic terms, of the ‘prevailingly, popular’ artistic styles of the ‘time’.

It is surely bizarre to level criticism on the [perceived] absence of a particular socio-sexual series of groupings. How does the reviewer know if any of the artists in this series fitted her socio-sexual criteria? Has she not heard of ‘context’? Not many people in the era of these particular artists were as forward in announcing their sexual ‘identities’ as they are now. That’s not their fault any more than it is irrelevant to what should be a properly professional, critical examination of the art, textual commentary, quality and production values that have made this such an outstanding, and much-needed series.

I find this review to be very flat. There is a basic lack of understanding of what drives an artist’s work. To paraphrase Dorothy Parker’s advice to a young writer, ‘If you can do anything else, do yourself a favor and do it, instead.’ In other words, art (or writing, music, dance, etc.) is a search that is both intoxicating and demanding. It demands one’s attention whether it is convenient, pragmatic or not. It is not the ideal career choice. Do something else. But, if you must be an artist. . . be prepared for indifference and flat, opinionated critics, then follow your heart, anyway.

The reviewer has a narrow socio-political lens of what merits an artist’s attention. Those are current considerations of some, I’m sure. But art is the one place where you can be FREE to pursue what you love. This reviewer’s current agenda is irrelevant to the world most of these artists lived in. Artists have always been a peripheral, marginalized and an inclusive community. The stigmas didn’t come from artists.

As far as career management & opportunities, that is each artist’s ‘cross to bear,’ as it were. Some are better at it than others. Ingenuity, energy, and multiple skills are usually abundant and available to artists, in some form or another to keep food on the table. That is separate challenge from the drive to make art. Success at the easel, doesn’t always attract the fawning critics, obviously.

I just finished “Bill Reid” by Doris Shadbolt. He managed it all quite well, in spite of various cultural prejudices to Indigenous expressions of art. As far as “tokenism,” that, too, is a current socio-political flag, that has sensitive relevance. But, it wasn’t experienced as that by Emily Carr or Arthur Pitts. What drove them was love of the art & culture of people around them and the joy to understand it through a deeper, more personal exploration.

Wendy Newbold Patterson

http://www.pattersonstudios.us

Burn, sizzle, sizzle . . . what to singe, Monica~~!

Thank you Wendy; we have a good sizzling conversation going here. What’s missing in action is our Ms Lamb. What is she thinking about these days? I have some excellent and hilarious cat memes that I could forward to her if she needs a laugh after all this. I prefer sardonic laughter to ideological fights that nobody ever wins.

Great post. Love the comments.

And here is the nuanced observation of a friend in the USA. Liana McCulloch gave me permission to post her comment, so here it is: “…what irked me was her comment that art is “rooted” in the socio-political climate of its time. Then she conflates the art of that time with her current political views and judges it as such. If I had a time machine and went back and spoke to some of these artists, I would ask them how rooted their art was in their current socio-political climate. I think their answer would lay somewhere between “I don’t know; I saw a bird and drew it!” to “Let history judge the meaning of my work”. It is not rooted at all. But what is important is that the cultural heritage of “humankind” is preserved so another generation is ABLE to ascribe meaning, yet still be mindful of the context in which the artist created their pieces without entirely hijacking it into whatever current socio-political fishbowl exists. Lamb’s review of the series did a disservice because its negative tone may actually deter people from reading the books because they are not “politically correct”…oy.

One must marvel at the courage of art critic Nellie Lamb in levelling the criticisms on the Unheralded Artists Series of Mother Tongue Publishing and proprietor, Mona Fertig (The Ormsby Review #573, July 4th, 2019). Lamb must realize that Fertig was well-served by her authors and their old-fashioned, journalistic approach to discussing the artists and their work. Surely the most important thing for Fertig was shining a light on a group that received little attention during their lifetimes and hoping, no doubt, that the rear-view mirror treatment might garner some belated appreciation as well as respect for these artists. That Fertig — as a publisher, editor, and author — has succeeded on that account there can be little argument. I have not read all the books but several are outstanding works of history and research, such as Peter Busby’s book on Jack Akroyd.

The old-fashioned and “popular” approach can’t be belittled, especially if one is to reach an audience not fitted with an art history verbiage app — and an audience that appreciates a jargon-free narrative from authors and critics alike.

There is so much to counter in Lamb’s analysis (which ranges from a missive to a harangue), but especially the lambasting levelled at the Unheralded Artists series for its lack of inclusivity. Inclusivity? To make the argument that these books are not worthwhile because they lack inclusivity is a bit feh in that it fails to acknowledge a structural and contextual problem, namely that that the art world, as well as the world at large, was not inclusive for anyone remotely connected to bohemia on the west coast of Canada.

Indeed one could argue that the art world now is more elitist than ever, as Joanna Mytkowska, Director of the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art, argues: “The contemporary art system is increasingly leaning towards the realm of the privileged one per-cent, whose aspirations cannot be shared by 99 per-cent of the public. The biggest museum boom has been in China and the oil-rich Middle-Eastern countries, which aren’t necessarily renowned for social emancipation. The future of the museum seems to rely on retrieving a direct link to the roots of artistic creation – and to a wide audience and its vision of the world. What needs to be found is a new sense of the word “public.” (What is the Museum of the Future?” Dercon, MOMUS, September 25, 2015).

No one can argue against embracing the narratives of those who feel marginalized but it is important to understand and realize that the artists represented in the Unheralded Artist series were, in and of themselves, marginalized. Thus, it is somewhat disingenuous of Lamb to proclaim, “They suggest that the art world should be more inclusive but they don’t really set a great example of inclusivity. They are against and outside the art world and yet their raison d’être is to include these artists in the art world.”

There is no contradiction at work here except, it seems, in the mind of Lamb, who conveniently de-contextualizes these artists from the past as non-marginalized, only to criticize the publisher for including them, thus robbing them of their status as marginalized due merely to the fact that the publisher has chosen to include them in a retrospective series some 40 years later!

Lamb’s statement that these 10 books do “little to convince me that these artists deserve careful attention” is nothing less than snide.

Thus, Lamb’s argument also flounders with slamming the series as lacking because there are no people with disabilities or different sexual orientations. It begs the question: were there artists of merit who were ignored due to aforementioned disabilities or sexual orientations? If so, kindly name them so we can know them. Is this the work of the future that Lamb points to?

The inclusivity card is used these days as a marketing tool to differentiate an artist’s narrative. The refugees from the dominant ideology are legion and the gallerists’ stable has every kind to choose from, it seems.

As I wrote in TOR/ Ormsby #397, in my review of Ullmann’s Rebel Muse, “Art in this era (and others) made for a fickle lover and an even icier taskmaster: a Siren that whispered alluringly in their ears and made them do things to undermine their long-term security. They devoted their lives to changing B.C.’s cultural landscape.”

But it wasn’t a heroic Hollywoodian end by any means. For most, the Canada Council was not yet doling out dollars to artists like Santa Claus and his bowl of candy at a Christmas parade. Far from it. Art — in all its sundry forms — was not a commodity in demand in the 50s and for most of the 60s. Pop art changed that, and the cultural capitals of New York, London and Paris flourished with their favourites and dealers. Vancouver wasn’t a part of it. Relatively speaking the whole BC art scene was marginalized and non-inclusive. This is what is galling in the statements.

So what isn’t galling in Lamb’s review?

In the moonscape of the west coast in the 60s, Native people, hippies and artists (and a tiny, few beleaguered academics) were the marginalized and by extension, the ones who initiated inclusiveness for themselves and like-minded spirits. They were brothers-and-sisters-in-arms in the fight to be heard above the din of the dominant ideology. As detailed in Fertig’s book on her father George Fertig, the chances for shows were far and few between at public galleries, and there were but a couple of private galleries. Yes, there were closet gays, Native artists, Metis, southpaws, Jews, Muslims…. but the art scene was tiny and nobody was consciously excluding anyone, and the collaboration among artists was significant, especially among sculptors.

Lamb, it seems, really digs herself into a hole near the end of the review: “They suggest that the art world should be more inclusive but they don’t really set a great example of inclusivity. They are against and outside the art world and yet their raison d’être is to include these artists in the art world. They begin to say something about the hardship of being an artist but it’s not thoroughly examined throughout the series and falls flat.”

Whew! I got lost in point-of-reference purgatory with this passage. The contention that “they” are against and outside the art world, while “their” raison d’etre is to include the artists in the series, is as muddled as it could possibly be. The 1950s and 60s artists in the series were not just against or outside the “art world,” and they certainly weren’t the same people who decided to include themselves in a retrospective of the early 2000s.

And Lamb states later that “they do little to convince me that these artists deserve careful attention, which is an unfortunate disservice to the artists. These books don’t make much of an argument either as stand-alone books or a series. They suggest that the art world should be more inclusive but they don’t really set a great example of inclusivity. The lack of an argument suggests that there really isn’t much to say about these artists other than to deliver a chronology about where they travelled, whom they married, and what jobs they took.”

Well, certainly Lamb has a point, but her dismissiveness is a little breathtaking, isn’t it? Sure, there could have been more rigour applied evenly to the books from an editorial point of view, but these were essentially stand alone titles.

No one that I’ve seen on this forum is arguing against inclusivity. Nor is anyone trying to administer an idle beat-down of a young critic. But I feel that Lamb fails to understand what the scene in BC was like in the 50s and 60s despite her family connections and her important and promising work and study in this area with books, painting and documentaries. I hope that she now has a better idea from which to extrapolate her theories.

I admit to be disquieted by this review. The more I think about it the more uncomfortable I am. Those of us who write for pleasure, or for a living, are well aware that perfection is not to be had. We do what we do from perspectives that are implicit or explicit in the topics at hand, the text, and the visuals.

To seek to shut down other writers in mass for having different perspectives and subject matter than we prefer is to my mind counterproductive in a book review, much less in a review essay considering ten separate volumes with a dozen authors and wide ranging subject matter. I for one would be far unhappier if the writers and artists agreed with my outlook, my world view, as opposed to having perspectives of their own and so challenging my thinking and expanding my horizons. To conclude, as the writer does, that “the series falls flat” and is “shallow” also, sadly, applies to this mean spirited, superior minded, single dimensional review.

Once again, an ‘expert’ or self-appointed critic with limited credentials, such as Ms. Lamb, is attempting to stamp the agenda with the oh-so-inclusive garbage that is masquerading as ‘dialogue’ in academia these days.

“…the most glaring misunderstanding of contemporary thought appears in The Life and Art of David Marshall, in which author Monika Ullmann suggests that modernist styles are “timeless” by way of criticism of curators who by the 1960s were no longer interested in showcasing Marshall’s large modernist sculptures. This assertion is incorrect — artistic styles are always rooted in a specific socio-political time. ”

Well, I have been put in my place, the place of dumb folks who don’t know the current right way to think.

How ironic this discussion is; it shows that there is still an ‘in group’, in this case the post modernists and the LB-something crowd. They now dominate intellectual discourse, and Ms Lamb is a product of the hot house atmosphere at universities all over Canada. To be clear: I didn’t say that modernist styles are timeless; my argument was that art that matters is timeless, not political, as Ms Lamb has been taught to think.

A Lamb in wolf’s clothing, she is attacking me because she is the product of the postmodernist virus infecting our universities. The postmodernists and their ilk think that there is only one right way to think, and it is richly demonstrated in this so called ‘review’. It’s nothing of the kind; simply a rather predictable litany of complaints about inclusiveness and lack of respect for aboriginals and other marginalized groups. It’s group think at its worst, and reverse racist, since it seems that the artists in the series are ‘too white’ to pass muster. Being the product of postmodernist ideology, the tiresome LB-something agenda and having no life experience outside of university and a couple of galleries, what does Ms Lamb actually know that isn’t doctrine?

The reviewer writes: “Even when an artist receives recognition and gets a show, it can be terrifying and wounding to share the work with critics, curators, and admirers who may misinterpret and misrepresent.”

This could be restated, in light of this review, as, “Even when an author writes a book, it can be terrifying and wounding to share the work with critics ….”

I read most of the books and found the art quite diverse both in style and quality but the artists’ stories surprisingly similar – the through line being the struggle to survive economically and the resentment of Vancouver’s little Art Establishment. This is instructive and valuable! But to criticize the series for what it isn’t, and to imply that there were “LGBT2SQ+ people, people of colour, people with disabilities, and other frequently marginalized voices” left out because of who they were, seems unfair.

“However, these books, like their subjects, are often out of touch with current concerns.” Well yeah, they’re historical biographies! It is for contemporary readers to examine them, and compare those lives and that art from a lifetime ago with the “current concerns” of artists. Most art is a response to its surroundings – I look forward to books about current unheralded artists and their concerns.

I don’t think Mona Fertig ever intended to suggest the series is some definitive list of THE unheralded artists of BC. These are just some she has identified. I am sure she, and all of us, would welcome others committing the time, passion, love, sweat and meagre financial resources she has had to producing similar portrayals of other artists. In the meantime I couldn’t agree more that each and every one of these books is a wonderful contribution to our world of art and knowledge.

It would be helpful — and more convincing — if the reviewer named some artists she feels should have been included, rather than lumping them together as “LGBT2SQ+ people, people of colour, people with disabilities, and other frequently marginalized voices”. Not naming them seems as bad as not including them in the series, and more deliberate.

Also, I don’t believe Mother Tongue intended any of these books to be a final in-depth dissertation — if more research is needed, please bring it on.

Comments are closed.