#537 From Tim Hortons to Swan Lake

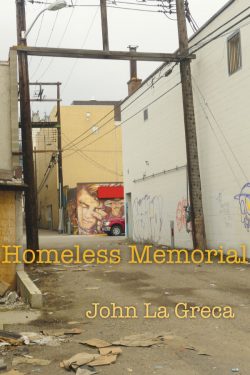

Homeless Memorial: Poems from the Streets of Vernon

by John La Greca

Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2018

$23.95 / 9781771712750

Reviewed by Phyllis Reeve

First published April 26, 2019

*

John La Greca would have been still in high school but already troubled and sensing his outsider status, at the time I spent a summer in Vernon with my children. I recall a little city close to the ground — no tall buildings, a great deal of space between pavement and sky, roads going out of town to who knows where — but a little city with deep roots.

John La Greca would have been still in high school but already troubled and sensing his outsider status, at the time I spent a summer in Vernon with my children. I recall a little city close to the ground — no tall buildings, a great deal of space between pavement and sky, roads going out of town to who knows where — but a little city with deep roots.

Patrick Lane wrote about a very dark side of Vernon. He couldn’t wait to leave, and once he did he seldom went back. John La Greca, on the other hand, left for a few years and returned to stay, although in the autobiographical epilogue he professes a desire to travel, even “to end the dead control of Vernon over my life.” In a sense, he is not “homeless.” His home is a community, or communities, both the community my family knew where people went home and closed their doors behind them, and the community La Greca portrays, which has more doorways than doors.

La Greca’s Vernon is a palimpsest of different realities. The poem “To Each Their Own” explores some unsuspected co-existences:

You say you have private property,

But have you? Who sits on your step at 10 a.m.,

While you work and buy groceries?

Who tokes there as you furbish your home

In blissful ignorance? Your neighbours are away, too,

About their concerns as well, no doubt.

Laughter is heard

As the dogs bark warnings no one hears,

As the dealers dispense their street trade

In your back yard, as the hookers lay their johns

In your driveway, parking not so nervously

Because they know, with certainty,

That the neighbourhood watch

Is down at the Schubert Centre having coffee

And boasting of the teenagers caught

Vandalizing garbage cans at midnight.

So, who sleeps in your yard for a few hours

While you sleep?

Who uses the back yard as a highway

To do evil the police know about

But are too lazy to get out on foot to detect?

Who uses your yard as a latrine?

Have you ever pissed on your land

To make it yours, as an animal would?

Your private land is community property

And you lack the sense to realize it.

It was not the cats and dogs

That set off the motion detector’s light — it was me taking a short cut.

After all, the police are at Timmy’s,

Out at the north end of Swan Lake

Catching drunk drivers

Or on manoeuvres for when the Brinks’ trunk

Does get heisted — ten minutes away,

Long enough to get hidden

On Black Rock with the Satanists.

The Schubert Centre (for seniors), Swan Lake, Tim Hortons (Timmy’s), and Black Rock Road are real places. I’m not sure about the Satanists.

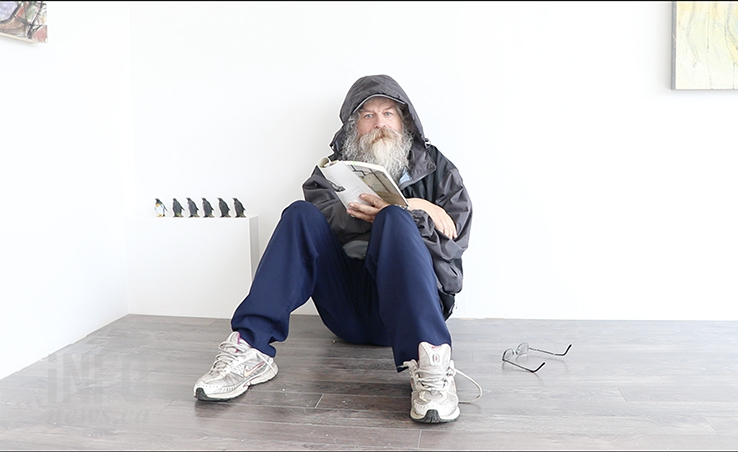

The poet himself is something of a palimpsest. Writing at age 64, he tells us:

I’ve been a client of government social agencies since I was 13. My grandmother evicted our family just before Christmas that year. My mother’s mental illness was causing antagonisms. It didn’t help that my father assaulted my mother’s brother while he was drunk…. I cracked up when I was 17. I took a year off after Grade Eleven. I was finding that I was a painter and a writer.

He was literally tearing his hair our because of an obsessive compulsive disorder. He briefly attended four universities: UBC and Okanagan College, and further afield Guelph and McGill, incongruously enrolled in Asian Studies and Public Relations. All the while he was reading widely and always writing. He shared his many poems with only a few people — his sister, his mentor the artist Sveva Caetani, who employed him for fifteen years as her gardener — and eventually the Vernon Library’s poet-in-residence, Harold Rhenisch, who guided him in the compilation and publishing of this book, introduced him to other writers and readers, and ushered him into the arena of book launches and media interviews.

The palimpsest communities are not “parallel;” they do intersect. We both frequented Polson Park, but at different hours of the day or night. One of the tragic characters in La Greca’s world “smoked crack/ on the ground at Fisher’s Hardware,” a local business for eight decades, and according to recent news stories still struggling with the incompatible co-existence of the customers on whom their livelihood depends and the destructive and self-destructive uninvited tenants of their parking lot.

Several poems tell stories of railway workers and machine operators with whom the poet occasionally worked, but most are vignettes, character sketches, and conversations featuring his fellow homeless citizens — vagrants, addicts, hookers — especially Brandi, “the most confusing woman I have ever talked to,” who wanted domesticity but suddenly died of natural causes or cancer or AIDS. “Brandi’s dead, and she’s still in my head./ She’s the gift that keeps giving back.”

In Vernon, I was fortunate to be introduced to several women who had led adventurous lives, climbed mountains, travelled, written, painted, and then as spinsters, widows or divorcees, lived alone aging graciously and giving back to the city. Sveva might have been one of these. She has her own poem, “Sveva’s God:”

…God became what God became

Because Sveva was cosmopolitan and democratic.

God would be found in knowledge of how to create a garden,

to make beautiful japanese cabinets,

to outdo the knowledge

Of carpenters, electricians and plumbers.

The poet’s voice is matter-of-fact and colloquial but highly literate, “cosmopolitan and democratic” like Sveva. His culture embraces both classical and pop. Consider these poem titles: “Terry Gilliam’s Revenge, or Move Over Montezuma,” “The Killer Breasts of Tchaka’s Body Guards,” “Waiting for Godot on St. Catherine Street One January Evening,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Now?”, “Margot Kidder and Former Topics of Conversation,” “Woody Allen, Now That He is near Death,” “On the Virtues on Being a Grasshopper” (a meditation on the 1970s TV show Kung Fu), “News, Cartoons and Madonna,” “A Moment with Dostoevsky before I Chainsaw the Crucifix Up above Bella Vista,” and “On the Song ‘I Will Always Love You.'”

This last is one of my favourites, a thoughtful, felt and tightly written comparison of Dolly Parton’s song with Whitney Huston’s cover from the film The Bodyguard:

Dolly Parton’s version

Is sweet, innocuous,

Not very memorable, non-sexual,

A song a mother listens to in her rocking chair;

Appealing to soporific tastes —

It is the summation of a juvenile

Teenage boy’s lust —

it’s there and you can’t do anything about it:

It is cheap, hurried sex when you do get it.

Whitney Huston presents

An intricate portrait; passionate, varied;

And hints at a love that may be lost.

An adult love, hurtful;

Not sadistic, farcical, or melancholic —

The things of Hollywood and magazines.

It is the pathos a middle-aged man remembers

As he cries himself to sleep

Ten thousand miles away in Japan.

I think the poem would move me even if I did not know that Dolly Parton is alive and well, and Whitney Houston isn’t.

The long poem “Homeless Memorial,” which gives the book its title, refers to a rock placed in Polson Park and an annual civic ceremony organised by the First Baptist Church as a means of “enabling our homeless population to remember friends and loved ones who have died in the past year.” The gesture is well-intentioned, but the poet observes that “The homeless memorial doesn’t get remembered,/ Except for once a year.”

The area around the rock, even the neighbouring gazebo, is neglected in a park which is otherwise meticulously maintained. The poet listens to and tells people’s stories, and offers no solution but is sure the memorial is not it. “The homeless deserve more than memorials, / Photo-ops or editors using them as political footballs / To beat both sides of the issue/ without proposing attacks on the problem/ And solutions that have a political will.”

The pastor’s undoubtedly sincere evocation of “our homeless population” puzzles. In what sense is the homeless population “ours?” How does it belong to the larger community? Is it to be embraced and given a party once a year? This memorial does not appear to have been the idea of the homeless, but of benevolent institutions and authority figures — the church, the John Howard Society, the city council. So, the memorial rock or ceremony is not the answer, any more than the bleak backstreet beautifully photographed by Rhenisch for the book’s cover, or any more than the trashing of the hardware parking lot.

John la Greca’s book has been much publicised and celebrated in Vernon and around the province. How will he be seen? A poet? A phenomenon? A representative of something? He emerges from his writing as very much an individual, but also on the edge of a community or several communities, each in need of what he has to offer. He reflects, “I have always felt denied as an outsider. In the prison and the psychiatric ward I was seen as a delusional person with grandiose thoughts about his own value. I always knew that I could contribute. ”

And he was right: he can contribute. We are told there are many more poems. I look forward to their publication.

*

Phyllis Parham Reeve has written about local and personal history in her three solo books and in contributions to journals and multi-author publications. She also contributed the foreword to Charlotte Cameron’s play, October Ferries to Gabriola (Fictive Press, 2017). She is a contributing editor of the Dorchester Review and her writing appears occasionally in Amphora, the journal of the Alcuin Society. A retired librarian and bookseller and co-founder of the bookstore at Page’s Resort & Marina, she lives on Gabriola Island, where she continues to interfere in the cultural life of her community. More details than necessary may be found on her website: https://sites.google.com/site/phyllisreeve/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster