#522 Nurse log and a Great Blue Heron

Upend

by Kevin Spenst

Victoria: Frog Hollow Press, 2018

$15.00 / 9781926948652

Reviewed by David Stouck

First published April 1, 2019

*

In Vancouver’s poetry scene Kevin Spenst was probably first noted for his inventive forms of self-advertising. To promote an early chapbook titled Fast Fictions (2007) he printed and distributed a map of where he would be reading his stories — fifty locations in Downtown and East Vancouver, all taking place on one day. His progress (“walk, bike, read, listen”) was filmed and uploaded to the Web; he urged passers by to come and hear him and, like a medieval busker, made his pitch for story telling. In 2014 he set out on a cross-country tour reading in 100 venues in Canada. In the following year he undertook a similar tour in B.C.

In Vancouver’s poetry scene Kevin Spenst was probably first noted for his inventive forms of self-advertising. To promote an early chapbook titled Fast Fictions (2007) he printed and distributed a map of where he would be reading his stories — fifty locations in Downtown and East Vancouver, all taking place on one day. His progress (“walk, bike, read, listen”) was filmed and uploaded to the Web; he urged passers by to come and hear him and, like a medieval busker, made his pitch for story telling. In 2014 he set out on a cross-country tour reading in 100 venues in Canada. In the following year he undertook a similar tour in B.C.

What strikes me in Fast Fictions is the challenge to our expectations of story telling. Some stories are so short and compact that we are forced to think about how short a story can be and not be just a joke or an anecdote: a coffee bean shivering on its way north; an eraser body-lifting a ruler but growing smaller instead of stronger. This cartoon humour expands in a story of a bossy bowl of soup giving the speaker orders. A longer story, “Manure Words” (though just two short pages) includes a two-legged dog named Lucky and a strange man who fertilizes his house plants by reading to them from the speeches of Gordon Campbell and other politicians.

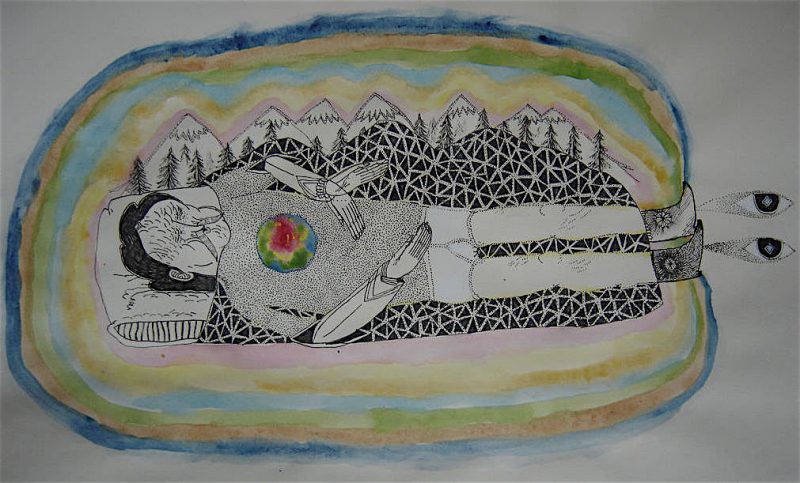

But in subsequent publications Spenst emerges as a poet rather than a prose writer, a very inventive and often a very serious one. In the Upend poems I was first struck by his rich choice of words and phrases (“a guild of small gnats, “straight-laced rain”) and his skill in writing in classic forms like the sonnet and the intricate villanelle. There is humour, a comic image for example of an old cedar in a storm that “pulled himself up by his rootstraps” and became a nurse log. There is a spirited parody of Lewis Carroll in “A Kloppervok in Stornly Bark.”

But in Spenst’s writing there is dark content as well. In a book of poems titled Ignite (Anvil Press, 2016) he introduced the figure of his father, a man living with schizophrenia who takes centre stage as he veers between the strict codes of his Mennonite faith and the chaos of his illness. He is a tragic figure searching for God and experiencing only despair. The impact on the poet son, and on his mother and three older sisters, comprises a wrenching family narrative that at 95 pages reads like a collection of short stories by Alice Munro, or a family narrative by Michael Ondaatje. Ignite was named a finalist for the Alfred G. Bailey Prize.

Upend is shorter, but creates a sharper, more searing distillation of the family drama. In the opening poem the frightened boy has taken cover under the coffee table; his sisters are absent and there is only the sound of “a baleen whale sighing,” of a heartbeat “that blubbered through the rooms of our house.” Eventually in the distance he hears a rattle of pills that orbits the father’s “slowing echolocation.” In another poem when his father’s medications are out of balance, he shelters from the “maelstrom of voices and eyes that sluiced the day” by hiding behind couch and sofa and mattresses — and “my hiding places became rafts.” In a poem titled “Everyday Versus the Imagination,” he recounts how he would play a game where his father was a stranger “and everything he said was spoken/ to another son standing behind me.”

Spenst uses the intricate repetitions and variations of the villanelle to embody the manic patient’s state of mind. To a poem titled “Relapsed Villanelle” he affixes an epigraph from poet Don Domanski, “a man is a piece of flesh / with a storm fastened to one end,” and the repeated lines in Spenst’s poem are variants on “He was a headwound alien seeping.” He presents his father historically as a lapsed Mennonite who “slumped under the skins of hundreds / of ancestors martyred for aloofness.” Instead of embodying religious ideals, Abe Spenst was “an alien headwound groaning.”

Three important poems in the latter part of the book focus on the author’s attempt to understand his father’s clinical diagnosis and his history as a patient in a psychiatric hospital. In “Nodes of Ranvier” (the title refers to gaps in the protective sheaths of brain cells) the poet claims a son’s right to access his father’s file from Riverview Hospital, but is informed by the hospital that “a person’s right to privacy does not diminish upon death.” He asks “what science, what fiction” does this signify? Eventually a two-page letter “crash-landed” at his door citing an easing of policy, and in “Dates of Admission” the reader learns of “30 pages of manic episodes” and grand mal seizures the patient suffered between 1954 and 1982.

Most moving is the poem titled “Required Reading” which details the father’s long struggle (and failure) to live a “normal life” — his work as a painter, rigger, ambulance driver, and the delusional episodes that bring him from euphoric states to moods of hostility and deep depression. The erosion of the father’s mental life is poignantly evoked by a final entry titled “Fossils of Three Haiku” where the father-son relation is reduced to a few sentence fragments.

But in Upend Spenst is not confined to family poems. In contrast to their sometimes untidy sprawl, there are several sonnets, celebrating his love for “Shauna” and for the natural world of forests and windstorms. I think the most artful of these is a poem titled “In Lost Lagoon” where, in a series of tightly chiseled metaphors, he celebrates the anatomy of a great blue heron. Its first six lines read:

The Great Blue Heron stakes its Jurassic claim

to silence. Under weighty robes, it cameos in a Noh

performance. Its orbital eyes on hold for its cue.

In the meantime, it dissembles into parts: knitting

needles, a garden hose, and the teardrop rear fender

of a 40s Mercury propped up on bamboo.

To borrow from the title of another of his poems, I would say this is a particularly striking example of poetry that unites the physical immediacy of “everyday” with the reaches of “the imagination.” The book is bracketed by two quotes that foreground the difficulty of saying things “right” — a challenge Kevin Spenst has met here in spades.

*

David Stouck is an editor and biographer. His latest book is Arthur Erickson: An Architect’s Life (Douglas & McIntyre, 2013). Editor’s note: David Stouck has also reviewed books by Theresa Kiskhan, Laisha Rosnau, Clea Roberts, and Eden Robinson for The Ormsby Review.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.