#514 Consider the Indian Act

21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act: Helping Canadians Make Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples a Reality

by Bob Joseph

Vancouver: Raincoast Books, 2018

$19.95 / 9780995266520

*

Talking Back to the Indian Act: Critical Readings in Settler Colonial Histories

by Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith D. Smith (editors)

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018

$29.95 / 9781487587352

Both books reviewed by Daniel Sims

*

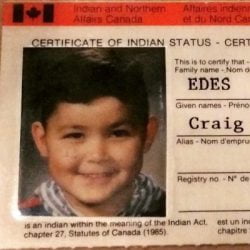

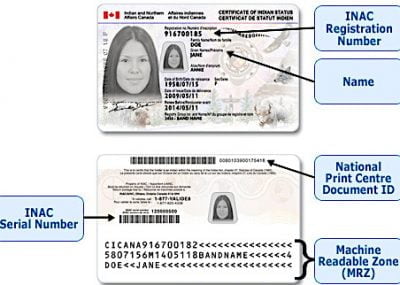

In my wallet is a piece of plastic issued by the federal government that clearly identifies me as “an Indian within meaning of the Indian Act, chapter 27, Statutes of Canada (1985).” It reflects that I have 6(1)(a) status and my status number is 609XXXXXXX. To someone familiar with the Act, and Indian status in particular, I just told you how I got status (technically no one is born with status) and what region and First Nation I am from. To someone uninitiated with the Indian Act, what I just said makes little sense. The first of the two books under review, Bob Joseph’s 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act, aims to rectify the latter situation.

For a piece of legislation, the Indian Act has come to symbolize many things to many different people, with some Canadians ruled by it and other Canadians unaware of its existence or what it means. First passed in 1876, it consolidated previous pieces of colonial (pre-Confederation) legislation that formed the nucleus of Canadian Aboriginal policy. Numerous amendments have followed, with the most recent ones made on December 22 2017 to try to remove sexism from the laws that determine who can get status.

Yet the Indian Act remains the only piece of current Canadian legislation aimed directly at a particular racial group. Many Indigenous people, including Bob Joseph, are calling for its complete repeal. But simply repealing the act is problematic, as was revealed in 1969 when Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and his Minister of Indian Affairs, Jean Chrétien, proposed to do so. They ran into the complexity of the things the Act legitimized and with which it was associated. I say legitimized rather than created because treaties, for example, predate the Indian Act and do not need the Act to exist or provide legal weight to them.

Bob Joseph is a hereditary chief of the Gwawaenuk Nation, which is itself part of the larger Kwakwaka’wakw Nation. The main Gwawaenuk settlement, Heghums (Hopetown), is on Watson Island, within their traditional territory in Broughton Archipelago on the north side of Queen Charlotte Strait on the Central Coast of British Columbia.

Not to be confused with his father, Chief Dr. Robert Joseph Sr., Bob Joseph is the founder and president of Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., commonly abbreviated as ITCINC. While in theory aimed at providing awareness training to organizations that interact with Indigenous peoples, the ITCINC blog has proven to be a major source of information for the public about Indigenous topics. As an instructor in both Indigenous history and Indigenous studies, I regularly have students consult and cite it, often in comparison to Chelsea Vowell’s Indigenous Writes or Lynda Gray’s First Nations 101.[1]

The title and list of “top” 21 items reveal the online origin of this book. To use a colloquialism, both are “clickbaity” and, frankly, reveal the genius of Joseph. Ultimately, 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act is about a piece of legislation. How then has it been consistently a bestseller since its release in April 2018? Partly Joseph wrote it in an easy to understand, approachable, accessible manner for readers with little to no understanding of the Indigenous situation in Canada.

The structure of 21 Things is suited to its intended audience. Joseph begins by briefly explaining what the Indian Act is, followed by 21 outrageous and unbelievable aspects of it, and concluding with his main argument that the Act should be replaced by Indigenous self-government. Forget the latest Indigenous theorist: the evidence Joseph cites, combined with the way he provides it to the reader, clearly explains why the Indian Act is inherently problematic. The five appendices, covering basic terminology, residential schools, and suggested classroom activities, show that Joseph wanted to reach the widest audience possible, including those within the classroom. I am considering using 21 Things in one of my introductory Indigenous studies courses.

This book’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness. Real life is complicated, and when introducing someone to a new concept or topic, it is important not to get bogged down in finer details, exceptions, and interpretations. 21 Things does not get caught up in these. For this reason, I would recommend it to anyone wanting to learn the basics of the Indian Act. To the specialist, however, in numerous sections of the book the lack of nuance is obvious. For the most part, it is insignificant. In a few instances, though, it does create problems because the legal and regional ramifications of the Indian Act are hard to understand in their entirety in such a short presentation.

For example, in talking about the right to vote, Joseph omits the property qualifications and regional limitations of the Electoral Franchise Act of 1885 when it came to the Indigenous right to vote (p. 80). Similarly, in citing 1960 as the year all Indigenous peoples in Canada could finally vote, he ignores the provincial franchise and the fact that in Québec, Indigenous people could not vote in provincial elections until 1969 (p. 82). This lack of specificity can even create contradiction. In Joseph’s section on enfranchisement, he states that:

Later, enfranchisement was extended to include Indians who joined the military. Indian veterans returning from World War II found that while they may have fought for their country, they had lost their Indian status in the process and had no home to return to (p. 30).

Not only are there numerous examples across Canada where this involuntary enfranchisement did not occur, but in a 2012 blog entry on the ICTINC website, Joseph himself writes that some veterans lost status because they had been absent from their reserve for four years, in violation of the Indian Act.[2] Further compounding the matter, Joseph also cites the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples on how Indigenous veterans were barred membership in the Royal Canadian Legion because they had Indian status (p. 44).

While a closer attention to detail would have avoided these issues, they do not diminish from the fact that 21 Things does what it was intended to do. And, of course, I am not the intended audience of this book. I have a Ph.D. in Indigenous history and have been studying and teaching the Indian Act, Electoral Franchise Act, enfranchisement, and Indigenous veterans for years. It is highly unlikely that the book’s average reader would know any of these topics in detail, and therefore any book delving into the finer points might cause needless confusion. Joseph simply wants to tell non-Indigenous Canadians why the Indian Act should be replaced — and he delivers, in 21 ways.

*

The second book reviewed here, Talking Back to the Indian Act: Critical Readings in Settler Colonial Histories, edited by Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith Smith, reminds us that the Indian Act is a relic of Canada’s colonial past. Its name captures this simple fact. In an era where the noun “Indian” is considered out-dated and offensive when referring to Indigenous peoples in Canada, the law governing many of their interactions with the Canadian state uses the term extensively, and in the case of status Indians, sets out how to define them. Because of this, the Act has resulted in numerous court cases in which Indigenous people take the Canadian state to court for the right to be Indians under the Indian Act (McIvor v. Canada 2009 BCCA 153; Deschaneaux v. Canada 2015 QCCS 3555). Yet to many members of the general public, the Indian Act is just like any other law, relatively unknown and unexamined.

Recently a number of books have been published that attempt to change this situation. Bob Joseph’s excellent 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act is aimed at beginners, while Kelm and Smith’s Talking Back to the Indian Act is aimed at those who know something about the Indian Act. Rather than merely introducing and discussing the Act, it encourages readers to combine the Five C’s (context, change over time, causality, contingency, and complexity) that drive the academic historical method, with the Four R’s (relationship, responsibility, respect, and reciprocity) that are fundamental to many Indigenous worldviews (pp. 23-24).

As part of this goal, Talking Back to the Indian Act seeks to teach the reader how to analyze original documents rather than simply cite them, even going so far as to provide no less than 28 questions a reader should ask of any primary source, in Appendix A.

That it aims for this outcome is not too surprising. The authors, Mary-Ellen Kelm and Keith Smith, are both university professors in Indigenous history and/or Indigenous studies, with Kelm currently holding the Canada Research Chair in Health, Medicine, and Society at Simon Fraser University and Smith the chair in Indigenous/ Xwulmuxw Studies at Vancouver Island University.

One of the big problems in studying the Indian Act is that one can easily get carried away with the complexity and context of the text or the level of scrutiny required. The Osgood Hall Law School, for instance, regularly puts out a collected volume of Aboriginal law, including the Indian Act, which is over 1,000 pages in length.[3]

Rather than try to cover the entirety of the Indian Act, however, Kelm and Smith limit their analysis to five key areas: the first Indian Act, governance, enfranchisement, gender, and land. They examine each one over time. Indeed, the chapter on the 1876 Indian Act runs from 1876 to 1983. This approach helps the reader understand the genealogy of the Indian Act. It also shows Indigenous agency when it comes to interpreting, responding to, and attempting to influence legislators capable of creating or changing it.

Kelm and Smith are not afraid to call a spade a spade. For example, not only do they discuss how the infamous Grand General Indian Council of Ontario and Quebec influenced the writing of certain sections of the Indian Act, they reproduce the very documents they cite. It is important to point out that neither Kelm nor Smith claim that this influence equated to consultation (pp. 48-53). Colonialism certainly does create interesting bedfellows.

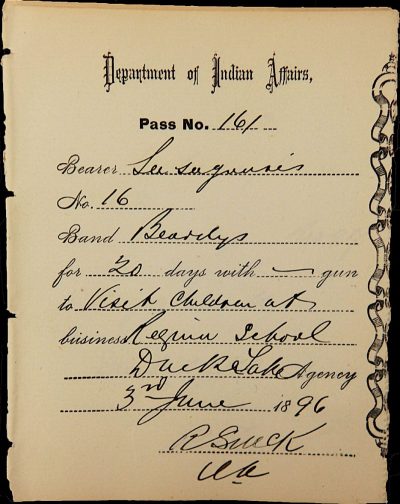

Beyond reproducing numerous original documents, the authors employ a wonderful selection of photographs, diagrams, and maps that greatly enrich the text. In particular, I really liked their visual representations of Bill C-31 1985 and Bill C-3 2010 — the failed attempts of the federal government to bring some gender equality to how status is determined (pp. 145-146). These really add to the text, and the photos help put a human face on the impacts of the Indian Act.

One of the biggest strengths of the book is the level of nuance one finds throughout. For example, as an Indigenous scholar who studies Indigenous history in British Columbia, I have developed a pet peeve in response to authors who claim that Canadian Aboriginal policy was the same from coast to coast to coast. In my view such statements are dangerously close to stating that Indigenous peoples are all the same. Such views also give the federal government too much credit by presupposing they had more power in the past than they actually had.

For this reason, I was quite happy to find Kelm and Smith acknowledged (p. 11) the British Columbia Aboriginal land question of the late 19th century — the province’s refusal to follow Ottawa’s Aboriginal land policy. This pleasure continued when the authors, rather than simply stating that Indigenous peoples had no concept of land ownership, observe that “for Indigenous people, land was not a commodity to be bought and sold, but an entity with which they were in a sacred trust relationship” (p. 18). At first these two statements might seem similar. The first, however — suggesting that Indigenous people had no connection to the land — is in concordance with the views of individuals like former B.C. Premier William Smithe, who stated “when the whites first came among you, you were little better than the wild beasts of the field.”[4] The fact that an erroneous notion of Indigenous land ownership is often held by self-proclaimed allies of Indigenous peoples suggests the insidious nature of colonialism.

Overall, I would recommend Talking Back to the Indian Act to anyone interested in learning about the Indian Act – or in learning about the historical method. It is an easy read and I expect to see it not only in my classroom but on my summer vacation this year. Pick up your copies of both books today.

*

A member of the Tsay Keh Dene First Nation in British Columbia, Dr. Daniel Sims is currently employed at the University of Alberta’s Augustana Campus as an Assistant Professor in History and Indigenous Studies. His research primarily focuses on Native-newcomer relations in western Canada with a particular emphasis on the law, environment, and economy. Currently he is working on two research projects. The first consists of turning his dissertation on the impacts of the W.A.C. Bennett Dam on the Tsek’ehne into a book, while the second examines the numerous failed developments in the Finlay-Parsnip watershed of northern B.C. during the early 20th century. He is also working an English translation of Einar Odd Mortensen’s book, Pelshandleren: Mitt liv blant Nord-Canadas indianere 1925-28, with Dr. Ingrid Urberg.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Endnotes:

[1] Chelsea Vowell, Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Communities in Canada (Winnipeg: Highwater Press, 2016); Lynda Gray, First Nations 101: Tons of Stuff You Need to Know About First Nations People (Vancouver: Adaawx Publishing, 2011).

[1] Chelsea Vowell, Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Communities in Canada (Winnipeg: Highwater Press, 2016); Lynda Gray, First Nations 101: Tons of Stuff You Need to Know About First Nations People (Vancouver: Adaawx Publishing, 2011).

[2] Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. (ICTINC), “Aboriginal Veterans: Equals on the Battlefields, but Not a Home.” Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. 2 November 2012: https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/aboriginal-veterans

[3] Shin Imai, Annotated Aboriginal Law: The Constitution, Legislation, Treaties and Supreme Court of Canada Case Summaries (Toronto: Carswell, 2019).

[4] British Columbia, “Report of Conferences between the Provincial Government and Indian Delegates from Fort Simpson and Naas River,” Sessional Papers: First Session, Fifth Parliament (Victoria: Richard Wolfenden 1887), p. 264.

4 comments on “#514 Consider the Indian Act”

Please release me let me go. Abolish the Indian Removal Act both US & CANADA: I’m so tired but I feel like jumping borders for better treatment. I live in Washington but want to go to Canada because they seem to be advancing to Abolish IRA. But I can’t, Canada closed the border against the virus. I hate this stupid number 04-177-10064-04 it stops me from owning land, makes me less than a US citizen with no privacy, suing a third time for discrimination, still the US refuses to list or call my race Inupiaq, saying I am Eskimo, a Danish racial word. All I do is pray and hope to anyone listening either to God, Satan or Whatever: Release me from my historical and collective Trauma. My soul is yours if that’s the cost! And I feel that something has returned, nknowing my secret name feels like Lord my Guardian Spirit or trickster’s nefarious work.

Comments are closed.