#511 Gold, gamblers, greenhorns

Gold Rush Manliness: Race and Gender on the Pacific Slope

by Christopher Herbert

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018

$30.00 (U.S.) / 9780295744131

Reviewed by Robert Hogg

*

Christopher Herbert has added to the considerable literature on gender in colonial societies, and of frontier masculinities in particular, as well as to the historiography of race, gold rushes, and colonial authority. Elizabeth Vibert’s Trader’s Tales: Narratives of Cultural Encounters on the Columbia Plateau 1807-1846 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), Adele Perry’s The Edge of Empire: Gender, Race and the Making of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 2001), and Robert Hogg’s Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), have enhanced our understanding of the intersection of gender, race, and frontier in colonial British Columbia.

Christopher Herbert has added to the considerable literature on gender in colonial societies, and of frontier masculinities in particular, as well as to the historiography of race, gold rushes, and colonial authority. Elizabeth Vibert’s Trader’s Tales: Narratives of Cultural Encounters on the Columbia Plateau 1807-1846 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1997), Adele Perry’s The Edge of Empire: Gender, Race and the Making of British Columbia (University of Toronto Press, 2001), and Robert Hogg’s Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), have enhanced our understanding of the intersection of gender, race, and frontier in colonial British Columbia.

Further south, Jacqueline Moore’s Cow Boys and Cattle Men: Class and Masculinities on the Texas Frontier 1865-1900 (New York University Press, 2009) and Albert Hurtado’s Intimate Frontiers: Sex, Gender and Culture in California (University of New Mexico Press, 1999) study the relationship between these factors on male-dominated American frontiers.

Herbert’s main argument is that the complex and strange environment of gold rush society forced white males to reconfigure ideas of race and gender. New ways of defining manliness evolved, based on ideas of work, republican ideology, risk and reward, differentiation from Indigenous and other non-white masculinities, and physical appearance. Herbert’s analysis is based on a binary conceptualisation of masculinity. Masculinity can either be “restrained,” that is, based on the values of prudence, hard work, thrift, self-restraint, sexual repression, and self-control; or it can be “martial,” based on dominance over subordinates. “Restrained” manliness was associated with the metropole — Great Britain or the urbanised eastern United States. “Martial” manliness was associated with the frontier and pioneering, and disseminated widely in popular culture.

On the gold fields of California and British Columbia, these masculinities blended. The conditions on the goldfields made it difficult to maintain all the lineaments of restrained manliness and many men embraced a martial identity. Nevertheless, the rudiments of metropolitan manliness remained and were adapted to local conditions. Furthermore, white manliness was defined against a range of racial and gender others in an explicit colonial society, with white men at the top.

Herbert contends that the combination of this particular form of manliness with whiteness allowed white men to be politically and socially dominant in gold field society. This was particularly so on the Californian goldfields where Anglo-Americans placed themselves at the top of the social hierarchy, superior to Indigenous peoples, African-Americans, Mexicans, and even (on the basis of their supposed criminality), Australians! [The reviewer is Australian]. Anglo-Americans believed that they embodied the ideal of the republican citizen and that their whiteness entitled them to dominion over the mines, the towns and non-whites. The drafters of the Californian constitution attempted to limit the franchise to “every white male citizens of the United States,” but were forced to include “every white male citizen of Mexico.”

However, the meaning of the word “white” was undefined. While it clearly excluded African-Americans, the position of the Indigenous, Mexican, Chinese, European, and mixed-race residents of California was more ambiguous. Here it became the job of authorities, elected and unelected, in the mines, towns, and cities to define and enforce white manliness. Built on pre-existing ideas of race and gender, laws governing access to the mines, a tax on foreign miners, and vigilante groups composed of “good citizens” buttressed white male Anglo-American privilege.

In British Columbia things were different. There it was Anglo-Americans who were perceived as the greatest threat to a stable and prosperous society. Absorbed into the British Empire in two stages (Vancouver Island in 1849 and the mainland in 1858), British Columbia, until the discovery of gold, was a fur-trading society ruled by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Even after becoming a British colony, the HBC wielded considerable influence in the form of Governor James Douglas, who was also a chief factor of the HBC.

With the discovery of gold and the arrival of thousands of Americans from the south, the most important issue was what sort of polity was British Columbia to be, one based on British principles or one based on American republicanism? Governor Douglas and the elites of British Columbia had well-formed opinions of Americans and they did not like what they saw. Whiteness, which meant so much to Anglo-Americans, meant less to the British than the former’s perceived propensity for violence and disorder.

Theoretically, all British subjects were equal under the Crown, entitled to protection under the law, and were not be discriminated against on the basis of race. In practice, this was extended only to those who met white, British standards of respectability. Savage, child-like, and irrational Native Americans did not qualify. However, English speaking, Protestant, black Canadians did. This was difficult for Anglo-Americans to abide. While Douglas tried to impress British values on Anglo-Americans by establishing a black police force, the resistance of the latter was strong. Eventually, Douglas’s black force was replaced by a white one, constituting a compromise on their racial ideas which the British believed differentiated them from Americans. For their part the Americans were willing to abide by the laws of the British, so long as those laws did not threaten their status as white men.

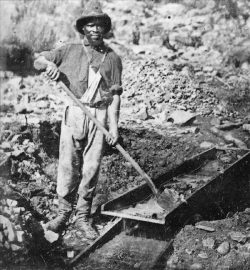

Gold prospecting was an inherently risky business, success being dependent to a large extent on “luck.” A careful, industrious miner could work hard for months without ever striking the prized lode. On the other hand, a less industrious, spendthrift miner might strike a fortune with little effort. Gold mining upset the received wisdom about the relationship between work, reward, and character that underpinned white conceptualisations of proper manliness.

Herbert’s examination of risk and its relationship to race and gender differentiates his study from those mentioned above and, to the best of my knowledge, other studies of frontier manliness. A dominant belief in white middle-class societies of the mid-nineteenth century was that hard work and perseverance would result in success. Experiences on the gold fields undercut this belief, as well as the path to white manhood through the attainment of financial independence and the practice of respectable leisure activities. Physical labouring of the type required by goldmining was redefined to make it acceptable for white middle-class men. Rather than the rough, dirty work characterising the labour of the working classes, the physical nature of mining was reimagined as noble.

The dominant leisure activity on the gold fields was gambling, more an activity of the rough labouring classes than the respectable middle classes. While widely practiced, gambling threatened the rectitude of white manliness. It could blur the distinction between “white” and “non-white” behaviour or produce situations in which Anglo-American men were equal or inferior to non-whites with whom they associated. There was no attempt by middle-class white men to reframe gambling as an indicator of white manliness. Rather, white manliness was defined against gambling thereby differentiating middle-class white men from non-whites. Although some of the specifics of the relationship between work, risk, gender, and race differed, there was a significant degree of continuity in these ideas between California and British Columbia.

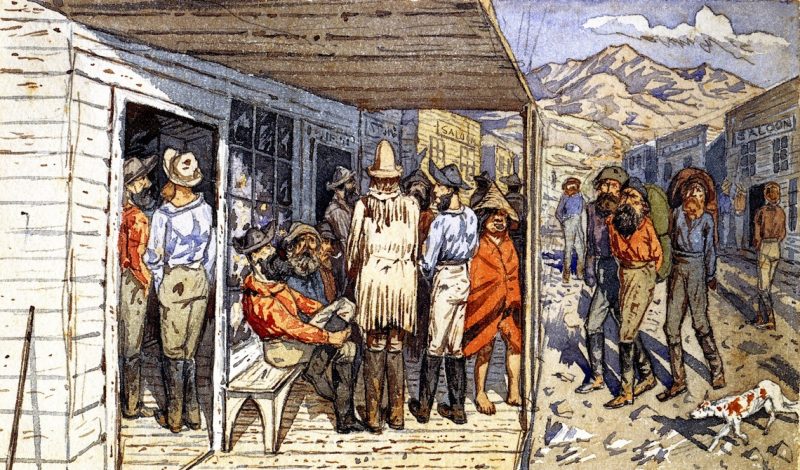

The final aspect of male gold rush society examined by Herbert concerns the clothing and physical appearance of miners. In the mid-nineteenth century appearance was held to be the key to understanding a person’s character. Observable filth and ragged clothing revealed inner deficiencies. Observable beauty and cleanliness marked inner purity and social worth. In gold rush society, where most people were unknown to each other, it was necessary to evaluate a person’s character by the way they dressed. Two things could mark a man as an experienced miner: guns and beards. The gold fields bristled with firearms, purportedly to protect oneself from Indigenous threats and violent crime. However, with crime rates on the goldfields comparable to those in eastern parts, the profusion of guns was more a function of middle-class white men’s desire to be manly, martial men than it was a response to actual conditions.

Clothing also distinguished the experienced miner from the “dandy” or “greenhorn.” The coarse and dirty clothes of the experienced miner set him apart from the kid gloves, walking stick, and patent leather boots of the newcomer, and the newcomers were usually clean shaven. The clothing and appearance of non-Anglos were also important in defining who was white and for bolstering the superiority of men’s bodies. Native people in both British Columbia and California were regarded as lazy, stupid, and submissive. In British Columbia Indigenous practices such as head-flattening were perceived by whites as evidence of lower intelligence and degrading sexual practices.

The obvious visual differences between Chinese miners and Anglo miners were measured against Anglo standards which saw any deviation as a degradation. The “portentous ugliness” of the Chinese was read as evidence of untruthfulness, knavery, cowardice, and thievery. One aspect of Chinese appearance drew particular reaction and that was the practice of wearing one’s hair in a long braid or queue. Most Anglo goldminers saw the braid as evidence of Chinese resistance to “civilised” standards and Western values.

Herbert’s style vividly evokes masculine life on the gold fields. The reader is swiftly immersed in gold rush society, its hierarchies, customs, and politics. Few in the academy would doubt that gender and race are important structural elements of any society. But it is important that we learn exactly how these variables operate in a given context at a given time. Herbert has ably demonstrated how they operated in mid-nineteenth century gold rush societies in ways that enabled the dominance of one class of men over others.

*

Dr. Robert Hogg has taught history at a number of Australian universities, primarily at the University of Queensland. He is the author of Men and Manliness on the Frontier: Queensland and British Columbia in the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). He is currently researching Australian and Canadian soldiers on the Western Front.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.