#472 Okanagan trade & cattle trail

Trail North: The Okanagan Trail of 1856-68 and its Origins in British Columbia and Washington

by Ken Mather

Victoria: Heritage House, 2018

$22.95 / 9781772032307

Reviewed by Harold Rhenisch

First published January 24th, 2019

*

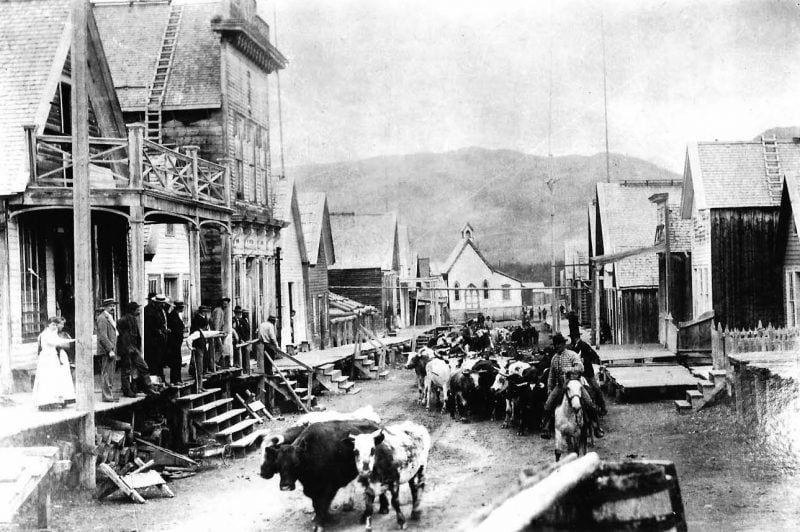

The British Columbia grasslands became cattle country, between 1858 and 1868, largely through the effects of a cattle route called The Okanagan Trail. For a decade, American cowboys, drovers, and traders brought cattle, freight, and culture into the B.C. Interior along it, and gold back south. They also brought guns and ammunition.

The British Columbia grasslands became cattle country, between 1858 and 1868, largely through the effects of a cattle route called The Okanagan Trail. For a decade, American cowboys, drovers, and traders brought cattle, freight, and culture into the B.C. Interior along it, and gold back south. They also brought guns and ammunition.

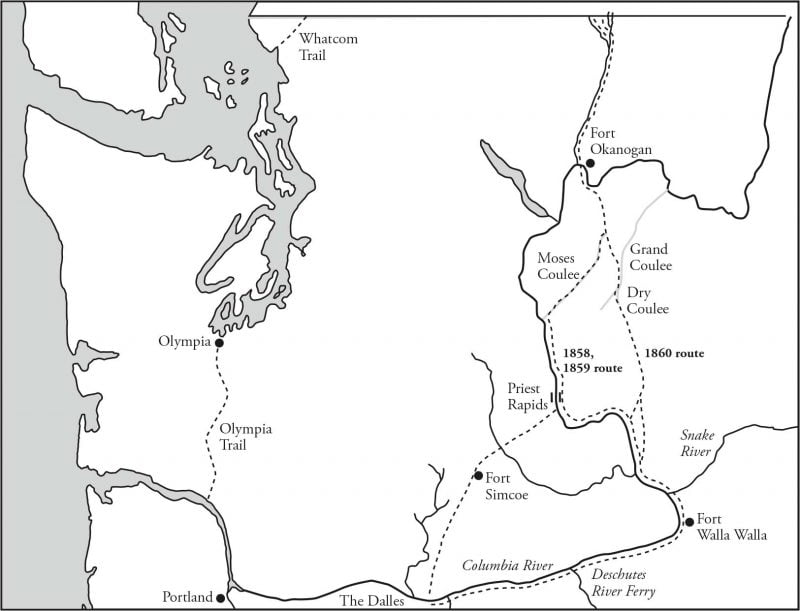

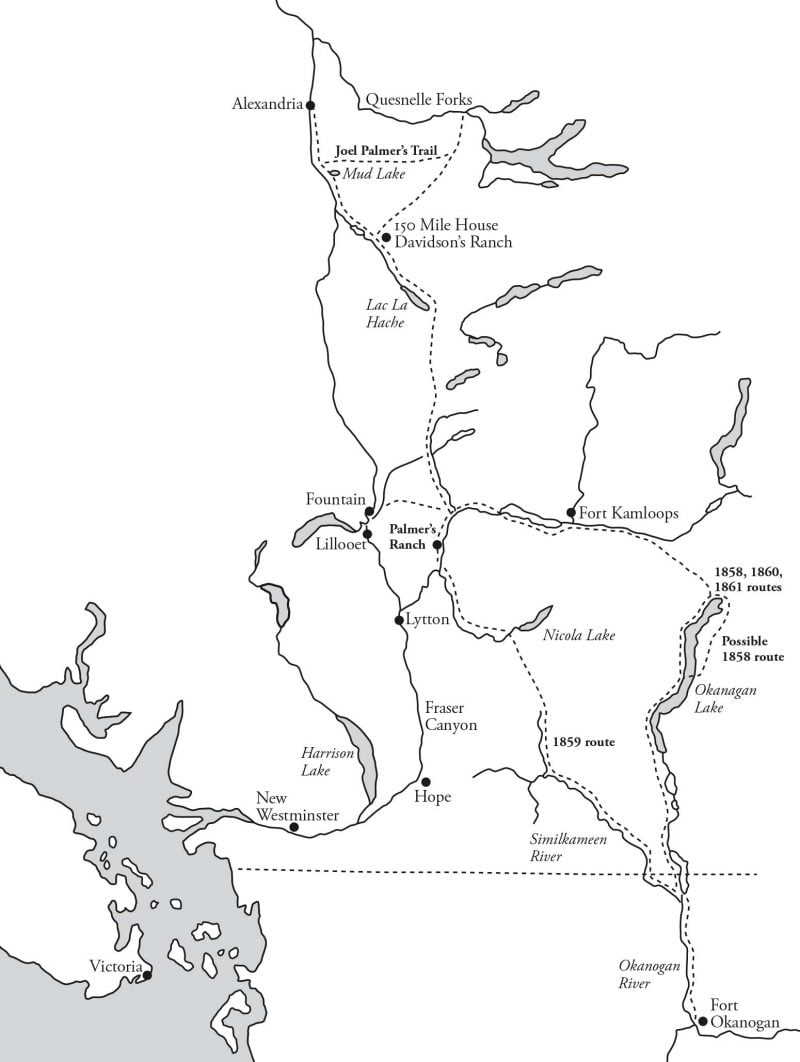

The trail stretched from The Dalles, Oregon, to Kamloops, Cache Creek, and the Cariboo Mountains. A side trail passed up the Similkameen and through Aspen Grove to rejoin the main trail in the Thompson. As the name suggests, much of the trail lies in the Okanagan Valley, on both sides of the U.S.-Canadian Border.

It is not a Canadian trail. It is an expression of American colonial culture. The first man to drive heavy freight up it in 1858, Joel Palmer, for instance, relied on his experience as an early caravan leader on the Oregon Trail (1845) and as Quartermaster General for the volunteer armies during the Cayuse War (1848).

Palmer built the trail as he moved north. The hardest part was in the Okanagan, where the going was so rough for his wagons that he had to cut a road out of the cliffs along Okanagan Lake north of Summerland. When he reached the rough climb to skirt the even more precipitous cliffs at Drought, north of Peachland, he gave up, rafted his wagons across the lake to Kelowna, and sent his cattle back to Penticton to come up over Okanagan Mountain on the east side.

Trail North is the story of driving cattle on this historically significant western trail. It tells of who the men were who did it, what their business was, how they fared, and some of their interactions with Syilx and Secwepemc people. Mather paints an effective portrait of a British Columbia built on the trail’s incursion of American economic might, capital, culture, and men into native space.

The trail itself is old. It predates the famous Chisholm Trail between Texas and Kansas by nine years. It was in use for two decades before the first beginnings of the Alberta cattle industry. Only the trail between Mexico’s Sacramento Valley and the Canadien settlements in Oregon’s Willamette Valley is older, and that by only a dozen years. Remarkably, that dozen years was enough to build herds in Oregon of such a size that a market became a matter of economic survival. The 40,000 Americans who came to the Fraser River from California to pan for gold in 1858 were that market. Note that they were Americans, served by Americans.

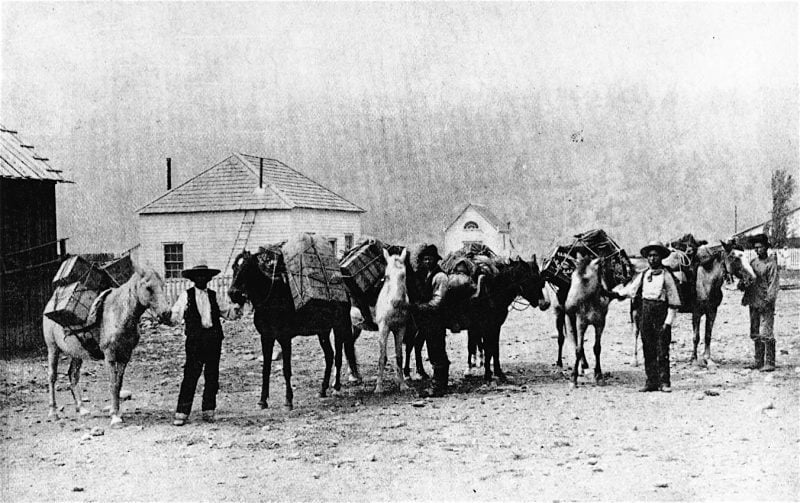

Mather describes in fascinating detail how the trail developed on a direct Mexican model and used Mexican packers, techniques, and equipment. Photos of men arriving in the Cariboo Gold Rush camp of Barkerville in 1861 don’t show cowboys. They show vaqueros, on Mexican saddles, driving long-horned Spanish cattle.

The story has even deeper roots, however. The North West Company didn’t make the trails. Nor did the Hudson’s Bay Company. The British Columbia sections were made by the Tsilqh’otin, the Syilx, the Carrier, and the Secwpemc over many thousands of years. The Washington sections were explored and laid down by the Sinkaeitk, the Sinkiuse, the Cayuse, the Walla Walla, the Yakama, the Wanapum, the Washaptum, the Chelan, the Umatilla, the Wishram, and the Syilx.

These ancient trails were used for transportation and trade and linked with important auxiliary routes. The central trading centres in this vast network were the salmon fishing centres of sx̌ʷəx̌ʷnitkʷ (Okanagan Falls) at the foot of Skaha Lake, Shonitku (Kettle Falls) in the mid-Columbia, and Celilo (as well as Wishram and The Dalles), at the eastern mouth of the Columbia Gorge.

These were not minor centres. At Celilo, for example, some estimates place 40,000 fishers and traders passing through every summer. The great traders of the Lower Columbia, the Tsinuk, exchanged shells and other coastal products, including metal trade goods, for hemp rope, workable stone, ochre, reed mats, buffalo hides, furs and other products of the dry country. Everyone traded for fish, often dried, powdered, and tightly-packed. Other traders came up from Mexico. Still others came with oolichan grease — a major trade good.

When languages failed, communication was in Chinook Wawa, a simplified universal trade jargon. It eventually added French and English from the Canadiens and Scots in the Willamette Valley and Fort Vancouver. It was in this language that the drovers of the Okanagan Trail communicated with the native people they met along the way. All treaties were negotiated in it. As it wasn’t a subtle language, communications weren’t always productive of cultural understanding.

It was on this Indigenous transportation network that the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company travelled, with the addition of boats on the Columbia section. Later, the Okanagan Trail was laid down by the mixed blood sons of retired fur traders, following their fathers’ footsteps.

These capable men, heirs of a rich culture, had no settled place in an increasingly racialized Oregon. Even more strongly, Washington culture made these men targets, often actively working to expel them as a potential fifth-column of British or Canadian culture within American space. In opposition to this ethnic cleansing, the trail allowed for new definitions of self and even, with luck, some White status, however temporary.

In some cases, the Americans on the Okanagan Trail obeyed no law, even their own. For the men who followed Palmer north, this was an armed road. They came with two months of ammunition, prepared to fight their way north and confident that they could.

These private armies were forbidden to make the trip by the U.S. Army, which was afraid they would draw the Canadian Syilx into war in Washington, but they came anyway. By blasting through Indigenous territory already pressured by war and illegal mining, they invited such native reprisals as theft of cattle north of Wenatchee, a bloody but failed ambush south of Tonasket, at least one lynching in the Boundary Country, and murder and attempted genocide in West Kelowna.

At first, British attempts at control consisted of a single customs house, south of Oroville, Washington, to catch traffic moving both up the Similkameen and the Okanogan. It was followed by one north of Osoyoos Lake, and another at Nighthawk, in the Similkameen. By the end of the road’s tenure, this control had developed into an expanded British legal system and an American-style land settlement regime that nearly eliminated all Indigenous industrial integration. Even native gardens and cattle pastures were erased, Mather notes with feeling and compassion, although they had already been Indigenous industries in British Columbia in 1858.

Effects on Indigenous people are noted in greater detail for the British Columbia section of the trail than for the Washington ones. Mather details precise responses to the trail’s violence, real or feared, from bands in the Nicola, but fails to consistently do the same for the southern sections of the route. He doesn’t, for example, note that the trail ran directly through the main Sinkiuse winter villages in Moses Coulee and in the Palisades Gorge leading up to it from the Columbia. Instead, he merely writes that the trail followed “an old native trail.” That’s less than precise. Chief Moses was still using it.

As another example, Mather records that canoes were appropriated in the old Hudson’s Bay Company gardens at Bridgeport, across the Columbia from Fort Okanogan, lashed together to form rafts, and used to move wagons across the Columbia. In addition, Syilx men were paid (sometimes) and tricked (sometimes) into providing transportation across the river. Mather does not comment on the distinction, or that the staging cattle were milling around in old native gardens. He simply tells the stories from a cattle drover’s perspective, as problems that had to be faced (which they certainly were.)

It’s quite a story, though, if you think about it. These native men helped the Americans even though they were virtually in a state of war with them. That some even tried to steal some horses and cattle midstream is hardly surprising. The inherent tension between points of view here is ample story for a detailed book on an Indigenous trail contemporary to and complementing the American one.

Mather’s integration of racial perspectives is also only lightly-sketched. He mentions William Peon, for example: first, as a man who discovered gold in Colville, which drew the attention of Oregon and Californian miners north; later, as a settler at Father Pandosy’s Mission in what is now Kelowna.

Sometimes absent is context. Peon, the son of either a Hawaiian or a Canadien father working for the Hudson’s Bay Company and a Spokane mother, was married to a Syilx woman and was the brother of Spokane chief Jean Baptiste Peon. William (and his father) were active in Secwepemc, Syilx, and Nlaka’pamux territory long before (and long after) Palmer. The Bonaparte Rivers in both British Columbia (a setting for much of Trail North) and Washington are named after his father. He himself was one of the men terribly wounded during the firefight in the ambush of the ill-fated David McLaughlin [McLoughlin] Party at Tonasket — which means he was one of the leading scouts and that this was, really, his trail, not Palmer’s or McLaughlin’s. A year later, Peon and his wife guided Pandosy through the same hostile territory to Kelowna. When challenged by native aggression, his wife negotiated their safe passage.

Not just Peon is opaque to Mather’s focus. To illustrate how the province developed alongside the trail, for example, Mather mentions that Pandosy created the first homestead in the Interior of British Columbia. He doesn’t mention that when Pandosy built his first winter shelter at Duck Lake, he did so beside the house of a previous French Canadian settler and his family. History records this man as a squatter, while labelling Pandosy as White. Mather would have been well-served by mentioning this Canadien, if only to erase the ridiculous distinction. Everyone was a squatter.

Such omissions are peripheral to Mather’s focus, yet indicate the depth of the Indigenous trail lying just underneath Mather’s and contemporary with it, yet including former Hudson’s Bay Company men (French, Scottish, mixed-blood, and Hawaiian), and their Indigenous wives, as well as their negotiations with race and place.

Mather hints at it with neutral commentary on the summary executions of native men in the Washaptum, the Yakima, Sinkius, and Spokane Country on slim if any evidence by the U.S. Army as it attempted to create peace for development. He also drops a tantalizing mention of Tonasket, one of the architects of the McLaughlin ambush, bringing six head of cattle up the trail. It would be good to know Tonasket’s reasons.

More troublingly, and closer to the core of his story, Mather tells of the role of the cattleman Jack Splawn. Splawn first came north on the Okanagan Trail in 1861, when he was 18, and was a leading drover on all the trails of the Pacific Northwest. He also had a history of shooting his way through contended territory against the express wishes of native people. Mather does not mention this violence.

But Splawn does. In his memoirs, he proudly admits that he used to shoot Indian men, and that he once pummelled a Washaptum chief for asking for compensation for running cattle across the mouth of the Wenatchee River and dirtying the water. Splawn mocks him, to his own shame. Mather would have done well to have presented a complex portrait of Splawn instead of a romantic one.

Actually, Mather has even lightly sketched-out a third book. Trail North contains tantalizing details that could easily be expanded on a tight theme. They include a short history of stock-raising in Oregon, as well as American workarounds of British land-ownership rules in Kamloops by using Indian Reserve boundaries as levers. That ruse involved successful deception of both British and Secwepemc men, with differing relationships to power.

An even more tantalizing vignette is of the economic stress the U.S. Civil War of 1861-65 placed on the trail. The war even played a direct role, when Confederate ranchers (the Jeffries brothers, Jerome Harper, and others) attempted to fund a privateer to attack Union shipping out of San Francisco.

The three books together would make a lovely set. While we wait for the other two, however, we have the solid research and clear writing of Trail North, with its long and fascinating section on Joel Palmer’s work to set up retail networks in the B.C. Interior as a kind of replacement for the Hudson’s Bay Company, but with T-bone steaks added to its list of retail goods. Despite its occasional oversights of alternative points of view, especially in Washington, it is an extensive gathering-in of threads.

Throughout, Ken Mather’s Trails North is passionate and thorough. In it you will find precisely where the trail went in what year, who used it, how they carried their gear, how many cattle they brought across year by year, and the problems they met along the way. The book is rich with maps. They are the most detailed and accurate I have ever seen and are worth every hour Mather has spent on the book.

In the end, the Okanagan Trail was short-lived because ranch settlement quickly followed it. As local beef production increased in the Okanagan, Thompson, Nicola, and Cariboo, the price plummeted. As the mines at Barkerville petered out during the late 1860s so did demand. Finally, in 1868 the flow of cattle north declined effectively to zero, and cattle from the Cariboo and the Okanagan flowed south to Hope instead. From there, stock was taken out to market down the Fraser River.

Altogether, Trails North sheds new and important light on 19th century British Columbia history. Ken Mather presents an amazing story of a trail that brought European civilization to the Interior and simultaneously created it as a wild space for blowing off pressures from inadequate systems of development elsewhere — while pushing people into narrowly-constrained roles. Mather’s is a hard story that portrays very real pressures.

The Interior retains an image of those systems to this day. The main border point at Osoyoos, mid-way in the Okanagan Valley and mid-way on the trail, remains one of the busiest in Canada, with trucking pouring into the Interior from Washington, California, and Mexico — maintaining a relationship set by Joel Palmer in 1858 and precluding, still, the need for settlement or takeover.

*

Harold Rhenisch was raised in the grasslands of the Similkameen Valley and has written some thirty books from the Southern Interior since 1974. He won the George Ryga Prize for The Wolves at Evelyn (Brindle & Glass, 2006), a memoir of German immigrant life from the Similkameen to the Bulkley valleys. His other grasslands books are the Cariboo meditation Tom Thompson’s Shack (New Star, 1999) and the Similkameen orchard memoir, Out of the Interior (Ronsdale, 1993). He lived for fifteen years in the South Cariboo and has worked closely with the photographer Chris Harris on his Cariboo-Chilcotin books published by Country Lights: Spirit in the Grass (2008), Motherstone (2010), and Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2016), as well as The Bowron Lakes (2006), and he writes the blog Okanagan-Okanogan: One Country without Borders, from his home in Vernon. For seven years, he has toured the grasslands of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho while working on Commonage, a history of the Okanagan region set in its American context, highlighting the American history of Father Charles Pandosy and situating the roots of the Commonage land claim in the North Okanagan in American colonial practice in Old Oregon.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster