#468 Power, petroleum, and pipelines

Costly Fix: Power, Politics and Nature in the Tar Sands

by Ian Urquhart

Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018

$39.95 / 9781487594619

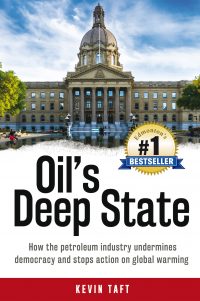

Oil’s Deep State: How the Petroleum Industry Undermines Democracy and Stops Action on Global Warming

by Kevin Taft

Toronto: Lorimer, 2017

$29.95 / 9781459409972

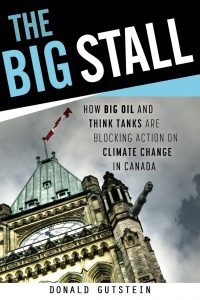

The Big Stall: How Big Oil and Think Tanks are Blocking Action on Climate Change in Canada

by Donald Gutstein

Toronto: Lorimer, 2018

$24.95 / 9781459413474

*

A joint review by Chris Tollefson

First published January 18, 2019

*

2018 was a year chock full of twists, turns, and Kinder Surprises.

Topping the list for those who follow the strange machinations of oil sands politics had to be the impulsive decision of the Trudeau government to spend 4.5 billion dollars of taxpayer money (with billions more in spending down the road) to buy the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion project (TMX) from Texas-based oil giant Kinder Morgan. Channelling the 1980s Remington razor pitchman and CEO Victor Kiam, the Trudeau cabinet apparently liked TMX so much, they “bought the company.”

The timing of this acquisition was a little off. A few months later, the Federal Court of Appeal struck down the Trudeau government’s earlier decision to approve the TMX project following a National Energy Board-led environmental assessment (EA) that had been loudly and widely criticized. Among the most vocal critics of this EA process, ironically, was Justin Trudeau himself, then on the 2015 campaign trail. He had promised to fix the federal EA process to restore the trust of Canadians in resource decision-making. After the election, his new government struck a blue-ribbon panel to advise them on how to do just that. Despite this, 2018 saw the Trudeau government ignore most of the panel’s sensible recommendations introducing instead Bill C- 69, a legislative mash-up that, from a sustainability, transparency and accountability perspective, is likely to be worse than the Harper EA law that preceded it.

Having installed itself as both the project’s owner/proponent and its ostensible regulator, and under unrelenting pressure by Alberta Premier Rachel Notley to get shovels in the ground before the end of 2019 (if not sooner), the Trudeau government remitted the job of fixing the defective TMX review back to the NEB, under the old Harper rules. And while the Trudeau government managed to get the House of Commons to pass Bill C-69 in June 2018, the bill is now hung up in the Senate, the target of a noisy misinformation campaign being led by a right-wing, astroturf group calling itself (I’m not kidding) “Suits and Boots.”

This entire hot mess is rolling out against a backdrop of deepening concern being registered by scientists worldwide – including in the latest IPCC special report (released October 2018) and in a precedent-setting health study in published in The Lancet — that unless sustained and dramatic action on climate change is taken within this generation, catastrophic climate related impacts will be inevitable.

The trajectory of the 2018 events chronicled above has largely unfolded since the publication of three astute and readable contributions to our understanding of the role and impact of oil sands politics on our democracy. For those struggling to comprehend the trajectory we seem to be on and what it would take to alter it, all three of these contributions offer some important insights: see Ian Urquhart’s Costly Fix: Power, Politics and Nature in the Tar Sands (University of Toronto Press, 2018); Kevin Taft’s Oil’s Deep State: How the Petroleum Industry Undermines Democracy and Stops Action on Global Warming (Lorimer, 2017) and Donald Gutstein’s The Big Stall: How Big Oil and Think Tanks are Blocking Action on Climate Change in Canada (Lorimer, 2018).

The most scholarly of these, at least in traditional terms, is by University of Alberta political science professor Ian Urquhart. His book, Costly Fix, tackles some sweeping questions of political economy deploying an historical approach that focusses on institutions, interests and perhaps most pivotally, ideology. The task he sets for himself is to understand the nature of the tar sands boom of the 1990s, an explosion of economic activity he compares to the Klondike gold rush. Why did this neo-liberal Klondike happen, what was government’s role, and who benefitted? These are all questions central to this carefully researched and provocatively argued tome. The sweep and density of the analysis will ensure that, for years to come, Costly Fix will be a standard text in the Canadian political economy canon, placing it in the company of such classics as Larry Pratt and John Richard’s Prairie Capitalism (1979).

Urquhart argues, like Taft and Gutstein, that the 1990s Alberta tar sands boom was facilitated and characterized by a radical departure in government resource policy. Both federally and provincially, he argues, the 1990s saw the prevailing nationalist “think like an owner” approach to resource management dissipate and ultimately discredited. In its place, a continentalist vision was soon embedded, steered by an ideology Urquhart refers to as “market fundamentalism.” And so, from the 1990s onward, the tar sands became the pampered and privileged child of Canadian government policy makers and influencers. According to Urquhart, what evolved was less an abandonment of regulation than a “re-regulation” that recast, in some basic ways, the subsisting bargain between capital and the state. In the process, the state — particularly at the provincial level — happily and completely abdicated its historic role in managing and controlling resource development and growth.

Kevin Taft, in Oil’s Deep State, covers much of the same storyline. Like Urquhart, Taft is intimately familiar with the frontier politics of Alberta, and with the political power of Big Oil. For a good chunk of time he chronicles here, Taft was an Alberta MLA (2001 to 2012) serving as the leader of the Liberal party opposition from 2004 to 2008.

Taft combines his insider knowledge with a crisp and hard-hitting writing style. He sets out to ask why democratically elected governments, at both federal and provincial levels, have so consistently failed to take action on climate change despite compelling evidence that the fate of the future generations hangs in the balance. The answer, in his view, is quite simple: “global warming is a death sentence for the fossil fuel industry” (p. 18). To delay that sentence, Taft argues that the industry has spent untold millions to capture key democratic institutions including political parties, governments, regulators, and universities.

While Taft’s book is an entertaining rant about the hijacking of democracy, he does display some scholarly chops as well. Of particular interest to those of a more theoretical bent, Taft spends some time usefully locating his approach to government capture in the burgeoning literature on the topic. While influenced by T.L. Karl’s Paradox of Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States (1997) and G. Monbiot’s Captive State: Captive State: The Corporate Takeover of Britain (2000), Taft hastens to emphasize that Alberta (and potentially Canada as well) are not “petrostates” but rather oil-dominated “deep states.”

While both situations involve a “hollowing-out” of the state and its capture by private interests, deep states emerge through a different trajectory. Petrostates are prone to arise in contexts where there is a weak or non-existent state with few democratic institutions (Venezuela and Saudi Arabia are offered as exemplars), while oil deep states are more prone to emerge in societies that “already have modern democratic institutions” (p. 206). As Taft puts it: “Petrostates are conceived in petroleum, while oil deep states are captured by petroleum” (p. 207, emphasis in original).

Both Taft and Urquhart colourfully convey a sense of the manic growth associated with the post-Lougheed era oil patch boom, and its consequences. According to Taft, the Alberta government sold the oil sands “at fire-sale prices” with industry “gorg[ing] itself until it grew so big, it began to trip on its own tentacles” (p. 162). As Urquhart puts it, the “irrational exuberance” of this period, “… encouraged by market fundamentalism’s impact on government decision-making, spawned a litany of damage, problems, and challenges” (p. 302).

Among the impacts chronicled is the price paid by nature and the environment in the Tar sands region (an area Urquhart refers to a “landscape of sacrifice” (p. 103), one that borders Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada’s largest national park and a UNESCO world heritage site). Urquhart also provides a nuanced account of the detrimental effects of the boom on Canada’s ability to meet its international greenhouse gas reduction targets.

Donald Gutstein’s latest book, The Big Stall, riffs off many of the same themes. A retired communications professor at Simon Fraser University, Gutstein offers a rollicking and opinionated diatribe about corporate power in an era of climate change rendered Chomsky-style through a blizzard of facts and information. More of a Shadbolt than a Bateman, Gutstein’s rendering of how powerful business interests and their propagandists have succeeded in blocking action on climate change is loud, proud and defiantly left-wing. Gutstein, like Taft, clearly relishes exposing the backroom deals and clandestine relationships, both in Canada and the US, that help explain the complex politics of climate change, a politics that all three authors would agree has become heavily corporate-dominated.

A provocative aspect of Gutstein’s analysis is his portrayal of the rise of what he calls the “New Gospel” — the notion that governments should respond to climate change by adopting business friendly policy tools such as carbon pricing. In Gutstein’s view, carbon pricing is a Trojan horse, a measure favoured by business for purely self-interested reasons. His book also offers a highly sceptical interpretation of the Paris Climate Agreement, which he calls “Big Oil’s Deal” due to its reliance on carbon pricing as a policy instrument while eschewing the imposition of binding national targets.

It is difficult to discern how much of Gutstein’s apparent distaste for carbon pricing is a function of his distrust of key carbon pricing entrepreneurs (called out for special criticism on this front are the Energy Policy Institute of Canada “EPIC,” the Canada West Foundation, and the Sustainable Prosperity Network) and how much is associated with his skepticism about market instruments generally. Despite a chapter entitled “Carbon Pricing: Economists vs. the Public Interest,” which includes a deep dive in the work of leading economic thinkers such as Pigou, Coase, and Crocker & Dales, the answer to this question remains unclear.

All three books recognize that the continuing power exercised by Big Oil is a function of both the efforts of the business interests and their traditional allies as well as the corresponding inability of potential counter-movements to gain political traction. Urquhart, in particular, tackles this complex question with some finesse exploring why Big Labour, environmental groups, and First Nations have yet to mount a serious challenge to the dominance of Big Oil. To some extent, these reasons relate to overt efforts by industry to co-opt potential opposition. Institutional factors that fragment and undermine efforts by opponents to have a voice in regulatory decision and policy-making also play a role, as well as more simply what Urquhart calls “the compelling and nature of the ideology of market fundamentalism” (p. 312).

Where all three books seem to run out of steam is on the most pressing questions of all: what would it take to alter the current grossly inadequate trajectory of contemporary climate law and policy? If this trajectory is being dictated by a broken or captured polity, do we need to fix our democracy first before entertaining any hope of having meaningful action on climate change?

Intriguingly, this is where our three authors part ways, at least somewhat. Gutstein concludes The Big Stall with a rabble-rousing chapter that exhorts us to question growth and to question (spoiler alert) economists. Instead, he argues, we should look to the courts and to Parliament to lend recognition to Indigenous rights and to push for the recognition of such rights internationally, including in international climate conventions. In his view, “Big Oil is correct to fear entrenchment of Indigenous rights in climate change treaties, since it could materially affect business as usual” (p. 245). He also suggests that we should likewise endow nature with binding legal rights to provide a counterbalance to the rights enjoyed by corporations both under domestic and international law.

Urquhart is less effusive. In his view, recent experience, federally and provincially, has demonstrated that the “institutional legacy” of Big Oil-friendly rules and institutions is highly resilient even in the face of dramatic electoral change. For Big Oil to be displaced from its dominant role in Canadian politics would require, in his view, substantial changes in the nature of the Canadian state, and for the issue of combatting climate change to acquire a much greater level of political/electoral salience. This, he acknowledges, may well “require a degree of mass political organization and mobilization Canadian environmentalism hasn’t seen yet” (p. 315).

Taft ends his book on a more optimistic note, with some very specific suggestions. In a concluding chapter, he argues that the end game must be “crossing the divide between a high-carbon present and the post-carbon future with determination and speed… the goal of humanity must be to reach zero emissions by mid-century, and even then we will need to brace for lifetimes of climate upheaval” (pp. 215-216). To this end, he emphasizes the importance of institutional reforms (noting, particularly, the need to overhaul the NEB and the Alberta Energy Regulator) and strengthen our democratic institutions to inoculate them from capture. Among other things, he urges tighter financial controls on and stricter scrutiny of the funding for political parties and universities, and “tougher restrictions on the movement of people among industries, the civil service and regulators” (p. 219).

A fundamental reality, opines Taft, is that climate campaigners should never assume that any government will take concerted action on climate change “unless it is kept under intense pressure for years at a time” (p. 220). Doing this will require mobilization on multiple fronts including electoral politics, the media, and before courts and regulatory tribunals.

All three books elucidate the challenges this mobilization will face. The urgency of mounting this mobilization is undeniable, not only as the result of the dwindling time we have left to curb global temperature rises associated with greenhouse gas emissions, but also due to pending actions and decisions on the political front. It seems pretty clear, for example, that the Trudeau government is bound and determined to grant regulatory approval to the TMX pipeline project, which it now owns, by mid-2019. To this end, it has required the NEB to complete its “reconsideration” of the project, with a view to addressing the flaws in its initial project assessment identified by the Federal Court of Appeal, by the end of February 2019.

So, within months, it is highly likely we will be embroiled in a second round of lawsuits and protests challenging the TMX project, and the process by which it has secured “re-approval” — a re-approval pursuant to the very Harper rules that Justin Trudeau promised, if elected, he would repeal to restore public trust, but which nonetheless still govern the TMX review process.

Perhaps there are more Kinder Surprises in the pipeline. In any event, how the TMX saga ultimately plays out, and indeed how the broader fight against climate change evolves in years to come, will speak volumes about the health of our democracy.

*

Chris Tollefson is a Professor of Law at the University of Victoria. His publications cover a range of environmental and natural resource law areas including environmental assessment, climate change, and access to justice. The 3rd edition of his environmental law text (co-authored with Meinhard Doelle) of Environmental Law: Cases and Materials (Carswell) is due out in spring 2019. Chris has appeared before all levels of court including the Supreme Court of Canada, and has represented public interest intervenors in various regulatory hearings including the Northern Gateway pipeline review, the Trans Mountain pipeline review, the Pacific North West LNG environmental assessment, and the Teck Frontier Oils Sands environmental assessment. He is a former Executive Director of the UVic Environmental Law Centre and served as Chair of the Ecojustice Legal Defence Fund. In 2016, he co-founded Canada’s first legal NGO focused on providing hands-on training for Canada’s next generation of public interest environmental litigators: the Pacific Centre for Environmental Law and Litigation (CELL), where he is executive director.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster