#458 From Powell Street to Tashme

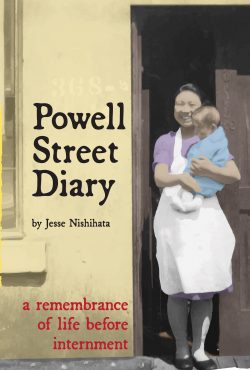

Powell Street Diary: A Remembrance of Life before Internment

by Jesse Nishihata, foreword by Junji Nishihata

Montreal: Tombo Communications, 2017

$20.00 / 9781387054060

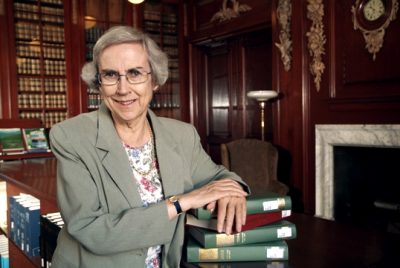

Reviewed by Patricia E. Roy

First published Jan. 1, 2019

*

In the foreword to this fascinating little book, Junji Nishihata explains that it began when his late father, the award-winning documentary film-maker Jesse Nishihata, sketched the background for a proposed television series. The elder Nishihata imaginatively created a diary that he might have written as 12-year-old Hideo who lived on Powell Street, the centre of Vancouver’s Japanese community, in the ten months after Pearl Harbor.

In the foreword to this fascinating little book, Junji Nishihata explains that it began when his late father, the award-winning documentary film-maker Jesse Nishihata, sketched the background for a proposed television series. The elder Nishihata imaginatively created a diary that he might have written as 12-year-old Hideo who lived on Powell Street, the centre of Vancouver’s Japanese community, in the ten months after Pearl Harbor.

Apart from describing the Latin origins of the word, “diary,” a rather sophisticated observation for one so young, and minor discrepancies in some details, the “diary” rings true. For example, Hideo mentioned how a classmate, Michiko Ishii, was always the first to volunteer. Now remembered as Midge Ayukawa, the author of Hiroshima Immigrants in Canada, 1891-1941 (UBC Press, 2008), she remained “on the get up and go” for the rest of her days (p. 18).

Junji Nishihata, who was born after the war, compares the internment experience of Japanese-Canadians to the “vivisection of the human heart” (p. 6). That was true for many adults; at least initially, it did not seem so for the mischievous Hideo. Some escapades were minor such as dropping pebbles on the tin roof of a Chinese restaurant from atop a neighbouring hotel. Others were more serious. A friend broke into a boarded-up Japanese shoe store, took shoes, sold them to other shoe stores and second-hand dealers, and shared the proceeds with friends, including Hideo.

For Hideo, Japan was simply his parents’ birthplace, but he did follow the exploits of the Imperial Japanese Navy in which an uncle served. Yet, like his classmates at Strathcona School, he believed “There’ll always be an England” (p. 23) On the night of Pearl Harbor he and a pal pretended to be RAF pilots.

Surprisingly, no “diary” entry refers specifically to the announcement in late February that all Japanese must move inland, but Hideo noted the arrival of new students from upcoast points and their later departure to Hastings Park. He was smitten with one new classmate, Christine from Woodfibre who briefly attended Strathcona School. On his first visit to see her at Hastings Park, he was astounded by the noise and crowded conditions and the contrast with the well-dressed white women quietly playing golf on the other side of the fence.

With his mother and siblings, he remained at home on Powell Street until mid-September. Apart from no longer having to go to Japanese Language School and having to endure a curfew, many things continued as usual. He still visited friends and relatives, attended grade seven classes, played marbles and other games, collected bottles for pocket money, went to the movies (an avocation which led to a career), and gathered driftwood to fuel the kitchen stove.

Yet, Hideo was aware of the war with blackouts, air raid drills, subdued celebrations of Christmas and the New Year, Japanese being held at the Immigration Building, the round-up of fishing boats, and the decline of his father’s tinsmithing business. The elder Nishihata, a Japanese National, went peacefully when ordered to go to an interior road camp, but several of Hideo’s acquaintances hid until they were caught and sent to the Angler, Ontario internment camp.

Moreover, Powell Street changed. Businesses closed and families left either on their own or to the government-operated camps. By the end of the school year as the grade eight students sang “We are leaving Strathcona. We are the graduates,” he chanted instead: “We are the evacuees” (p. 79).

Shipyard workers and their families moved into vacated residences. A boy from Saskatchewan was a friend until he made derogatory comments about the Japanese and the actions of their army in Nanking in 1937.

Eventually, with his mother and siblings, Hideo left for Tashme, the government operated camp just east of Hope, where his father was already building houses. A few paragraphs about Hideo’s life between leaving Vancouver and emerging as a film maker would have been a welcome addition to the foreword.

As a child’s view of the disintegration of Powell Street as a Japanese community, the “diary” is an unusual contribution to memoirs of the critical months after Pearl Harbor. It would be a fine way of introducing Middle School students to the wartime experiences of the Japanese Canadians.

*

Patricia E. Roy, a native of British Columbia, is professor emeritus of History at the University of Victoria where she taught Canadian history for many years. Her own research has been mainly in the field of British Columbia history and she is best known for her trilogy of books on the responses to Chinese and Japanese immigrants: A White Man’s Province (1989); The Oriental Question (2003), and The Triumph of Citizenship (2007). All were published by UBC Press. Her longstanding interest in B.C.’s political history resulted in Boundless Optimism: Richard McBride’s British Columbia (UBC Press, 2012). Her latest book is The Collectors: A History of the Royal British Columbia Museum and Archives (Victoria: Royal British Columbia Museum, 2018).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#458 From Powell Street to Tashme”

Comments are closed.