#452 Jewish arrival and survival

Seeking the Fabled City: The Canadian Jewish Experience

by Allan Levine

Toronto: Penguin Random House Canada (McClelland & Stewart), 2018

$45.00 / 9780771048050

Reviewed by Sheldon Goldfarb

First published Dec. 21, 2018

*

Have you heard the one about the Winnipeg paper that tried to explain the ways of this strange new people, the Jews, by saying their prayer services were led by Rabbits?

Have you heard the one about the Winnipeg paper that tried to explain the ways of this strange new people, the Jews, by saying their prayer services were led by Rabbits?

Or how about the Ottawa synagogue that discovered to its dismay that it was next door to a pork processing plant which wafted the smell of pork through the congregation during services?

Or the “Dairy Synagogue” in Winnipeg whose congregation was made up of milkmen.

Allan Levine has certainly found a few amusing moments in the history of Canadian Jews, at least in the early years of the Jewish experience in Canada. Of course, there were darker moments too: anti-Semitic outbursts, quotas that kept Jews out of professions and universities, slurs, riots. Why, it turns out that even the beloved children’s classic Anne of Green Gables shows Jews, or one Jew, in a less than flattering light: the peddler who sells Anne the dye that turns her hair green? A German Jew.

And then there was the Jewish family that claimed to own Labrador and the Jews who tried to make a go of it as farmers in Wapella, Saskatchewan: Jewish farmers? Who ever heard of Jewish farmers? And from Levine we also learn how one of the earliest Jews in Canada, Moses Hart, abandoned Judaism in favour of a religion of his own invention.

Interesting stuff, but after these early stories Levine settles in to telling a fairly familiar story about the two main early waves of Jewish immigrants who came to Canada, mostly to Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg: first, the German and British Jews, then the Russian-Polish Jews, upon whom the first wave looked down, and who struggled at first in poverty until discovering prosperity in the Second World War and moving to the suburbs.

But wait, none of that applies to Vancouver. Vancouver was an outlier, Levine says; it didn’t follow the same evolution as the leading Jewish centres — but what he neglects to mention (except in a table at the end) is that in recent decades Vancouver has become one of the leading centres, with the third largest community in the country, far surpassing Winnipeg, the former third largest.

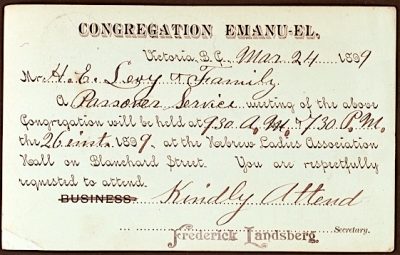

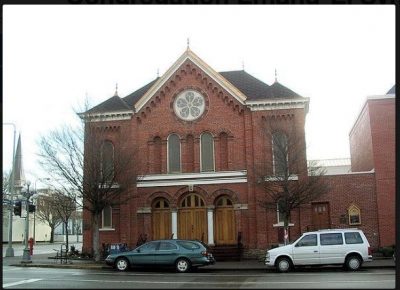

And why is that? The mild climate, he suggests, as if that is a new development. The growth of the Vancouver Jewish community deserves much more attention. There’s even a question about whether it is a community. Historically, Vancouver (and also Victoria and the rest of the province) developed differently: rather than a wave of immigrants from the Old Country, British Columbia saw individual Jews arrive singly from elsewhere in North America, partly drawn by the 1858 gold rush. Perhaps as a result Jews were always more integrated into non-Jewish society here.[1]

Levine makes a big deal about Toronto electing a Jewish mayor in 1954, but Victoria elected one (Lumley Franklin) in 1865 and Vancouver did the same in 1888, elevating David Oppenheimer, who even has a statue in Stanley Park for the work he did in creating it.

Of course, integration is not just a blessing. Levine cites the astonishing statistic that 73.5 percent of Jews in Victoria marry non-Jews. Vancouver is not far behind, at 43.5 percent. How can a community survive like that? And what is a community like that? What is it like in the household of the intermarried?

Levine spends a few paragraphs on a Toronto family and how they carry on Jewish traditions, but that’s a family with two Jewish parents. What happens when there is only one? What is it like when one parent has converted? Although Levine quotes a statement to the effect that Jews are all individualists and notes the complexity and diversity of Jewish life today, he does tend to homogenize. We learn nothing about what it is like to live in an ultra-Orthodox Hasidic family or in a family of Jews from Morocco. What was it like in families of Communist Jews back in the Depression? (Jews were prominent in the Communist movement back then and in the immediate postwar period.)

One major problem in Levine’s book is that he is either at too high an altitude, showering us with statistics and talking about distant organizations like the Canadian Jewish Congress, or spending too much time compiling a Jewish who’s who: telling us where such and such a Jewish leader went to school, who he (or she) married, how they became interested in art, how they died: I suppose this might be useful for reference but it seems just a diversion from telling us about the inner workings of the Canadian Jewish experience. For that you might be better off reading a novel by Mordecai Richler.

It does raise an interesting issue, though. Levine quite rightly points out the anti-Semitic sort of comment that complains that the Jews have too much power or influence. And yet he delights in pointing out Jews who have made it, who are successful, who in fact do have influence.

One begins to think, Can we have it both ways, celebrating influence but criticizing those who say there is too much? I suppose it is the “too much” that is key: how much is too much? And if a people have achieved, why should they be criticized for that?

Also, how is it that the poor Jews of the Depression have become so successful? How did the barriers to their advancement fall? Levine notes that, though the Holocaust shocked Jews and non-Jews alike, discrimination didn’t really fade away until the 1960s. Why is that? Levine credits Pierre Trudeau and multiculturalism which celebrated things like Israeli folk dancing (oh, please, not Israeli folk dancing). Maybe it was just the general Sixties zeitgeist, the civil rights movement in the States, and so on.

Anyway, there are interesting questions that come to mind reading Levine’s book, but they deserve a fuller treatment than he affords them. We could use a book that explores them, and especially explores the varieties of Jewish experience, tracing the trends in Canadian society, and we could especially do with a new book on the Jewish community in Vancouver and Victoria.

*

[1] For more on this topic, there’s a book that Levine does not mention: Lillooet Nördlinger McDonnell, Raincoast Jews: Integration in British Columbia (Vancouver: Midtown Press, 2014), which is based on her PhD dissertation, “In the Company of Gentiles: Exploring the History of Integrated Jews in British Columbia, 1858 1971,” University of Ottawa, 2011.

*

Sheldon Goldfarb is the author of The Hundred-Year Trek: A History of Student Life at UBC (Heritage House, 2017). He has been the archivist for the UBC student society (the AMS) for more than twenty years and has also written a murder mystery and two academic books on the Victorian author William Makepeace Thackeray. His murder mystery, Remember, Remember, was nominated for an Arthur Ellis crime writing award in 2005. Originally from Montreal, he has a history degree from McGill University, a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba, and graduate degrees in English and archival studies from the University of British Columbia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#452 Jewish arrival and survival”

Comments are closed.