#445 Sitting pretty on Burrard Inlet

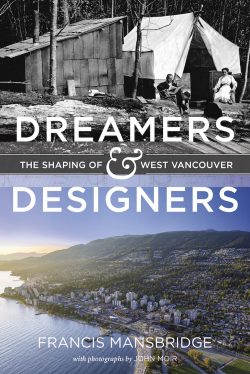

Dreamers and Designers: The Shaping of West Vancouver

by Francis Mansbridge, with photographs by John Moir

Madeira Park: Harbour Publishing, 2018

$29.95 / 9781550178517

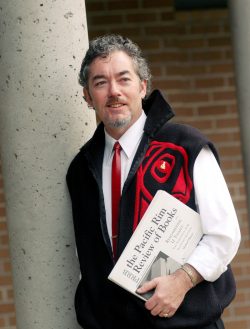

Reviewed by Trevor Carolan

First published December 12, 2018

*

Illustrating Irving Layton’s maxim that “Geography is fate,” this newest exploration of West Vancouver’s development as a civic and cultural polity focuses on it location, ecological profile and the development of its built community.

Illustrating Irving Layton’s maxim that “Geography is fate,” this newest exploration of West Vancouver’s development as a civic and cultural polity focuses on it location, ecological profile and the development of its built community.

As author Francis Mansbridge notes, the first non-Indigenous year-round resident here was Navvy Jack Thomas in 1866. He ran the boat shuttle between what would become Vancouver and a wild stretch of shoreline and slopes above English Bay and Burrard Inlet, colloquially known as the North Shore. About 1899, Francis Caulfield from Devon purchased about 1,000 acres adjacent to the waterfront east of Horseshoe Bay and set to sub-dividing it in a rambling, utopian fashion calculated to recall the idiosyncratic country charm of southern England.

Already, what we now know as the District of West Vancouver was on its way to becoming the wealthiest (by postal code) residential area in Canada.

By 1905, a British immigrant named John Lawson arrived by rowboat from downtown, bought land in what is now Ambleside, and took over supervision of the community ferry. He made his civic mark accordingly, and the summer’s annual Harmony Arts Festival — one of B.C.’s very finest — takes place in the comfortable waterfront park named in his honour.

Always a sanctuary for creative souls from the major city across English Bay, West Vancouver’s long south-facing waterfront and “Green Wall” mountain backdrop have long made it a desirable location to play, live, and (for a comparative few) work. British cultural traditions have long ruled the roost, and residually in terms of voter democratic expectations continue to do so. However unfashionable it may sound in these post-colonial times, West Vancouverites don’t much bother what others think about them. Every morning when they open their curtains they know that they still have a jewel, and it’s the place where pretty well anyone would like to live. As the author observes, overall West Vancouver’s growth has been deliberately slow, and until quite recently ethnic change in the social mosaic has been lower-profile too. Things get done there, services are good, the views are stunning, crime is negligible. And before one forgets, the average price of a home in 2017 was $3.1 million.

Unsurprisingly, housing affordability is a thorny issue, especially for seniors and the vulnerable. As of 2012, only 224 social housing units existed in West Vancouver. Meantime, ironically, in the nation’s swankiest area, 51 percent of seniors there earned less than $30,000 annually.

Mansbridge sidebars his narrative with digressions into various planning and design issues or precedents, and these will be useful for lay readers who are unlikely to be archivists or members of the Urban Design Institute. In one, he discusses how urban planning as a concept took shape in 19th century Britain as a means of giving the middle-class better conditions: a cursory read into the origins of the Bloomsbury literary group, for example, reveals how their preferred residential turf in London was quite literally an invention, a purpose-designed residential area away from the dirtiness of the city centre. By 1916, North America was thinking in similar patterns.

As the book’s excellent archival photographs illustrate, West Vancouver found early traction as a vacation and recreational for Vancouverites. Camping and constructing summer cabins were popular pastimes along the waterfront-adjacent flat lands. Fishing was productive, bird and deer hunting on the lower mountain slopes was good, bear was available in Capilano Canyon, and mountains goats higher up. Seasonally, as the photographs support, it could be an utterly idyllic haunt and this continued into the 1920s.

Yet if life was good for the vacationers from town, Mansbridge demonstrates how it remained a challenge for those committed to actually living in West Vancouver and seeing it grow. Being viewed as a rustic vacation spot brought its own limitations, principally low tax revenues. By 1926, Town Planning By-law 308 declared “…the presence of tents and huts [to be] unsanitary.” It also led toward the division of the municipal district into the Ambleside, Dundarave, Caulfield and Horseshoe Bay areas. That same year, Pacific Stage Bus Service began connecting the West Vancouver community of 7,000 with downtown Vancouver via the long, roundabout Second Narrows crossing of Burrard Inlet at North Vancouver, (Malcolm Lowry would become a colourful user of this service just over a decade later). Progress was being made.

Most homes in West Vancouver remained cottage-style dwellings. As Mansbridge relates, it was the vision of Councillor Joe Leyland that “spelled the eventual end of the Huck Finn existence” many families enjoyed and that painters like the late Unity Bainbridge celebrated with their images of dairy farm life and cows at Ambleside.

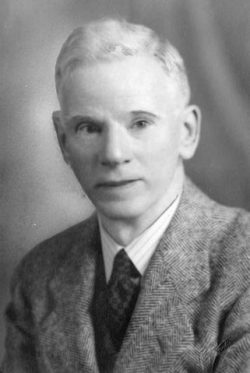

The book features an especially good biographical profile of Leyland. Facing a situation similar to that of our present moment in Vancouver, in which absentee owners are regarded as the new civic baddies, Leyland understood that West Vancouver’s future pointed directly toward the development of upscale, year-round single-family residences. To this end, for a half-century he worked toward achieving a fundamentally more cohesive, unified community.

Never a philistine, Leyland also recognized the value of the creative arts: his grandfather had been a close friend of Branwell Bronte, brother of the three Bronte writing sisters at Howarth, Yorkshire, and wrote a two-volume work on the family. The son of immigrant parents, Leyland was elected to local Council, and supervised the building of the Capilano Bridge in 1930. He advocated for a road up Howe Sound to the Garibaldi recreational area — now known as the Sea-to-Sky Highway to Whistler. Never short of vision, Leyland also proved a dynamic force in lobbying for a bridge crossing at Lion’s Gate.

Mansbridge explains how in 1931 the Guinness family’s British Pacific Properties paid West Vancouver a paltry $75,000 for 4,000 acres of uphill land that stretched from the Capilano River to Horseshoe Bay. While not as stupendous a bargain as the purchase of Manhattan Island from the Lenape indigenous people for sixty Guilders, or William Seward’s purchase for the USA of Alaska from the Czar, the West Vancouver Highlands deal ranks as a major contender in historic civic boondoggles. British Properties has reaped bonanza profits through the years and, as the book points out, they’re not done yet. The era of super-big homes in the Properties was soon to begin. At approximately the same time, winter skiing took off on the slopes higher up as better-off recreation enthusiasts began taking to the snow.

This was also, Mansbridge informs, the decade to have a — you guessed it — rustic log cabin built somewhere along Hollyburn Ridge behind and well up the slopes from the big homes. In effect, once the modest shacks had been cleared from out front in the vicinity of the beaches and old tidal flats, it was now fashionable to own one in the bush out back. Apparently, as many as 300 of these private, unserviced ski cabins were built and — in this reviewer’s experience — a good few still function comfortably in a mountain hamlet-type arrangement among the trees. Prime Minster Justin Trudeau’s maternal grandparents, the James Sinclairs (through his mother Margaret), were fortunate to own one.

Meanwhile downslope, the opening of the Lion’s Gate Bridge in 1938 was a land speculator’s dream. West Vancouver had seen a sufficiency of real estate boom and busts, notably in the Horseshoe Bay area. With planning still dominated by the local Chamber of Commerce, local residents were obliged to get involved in trying to maintain something of the semi-rural charm of the North Shore’s western area. By the 1940s, a new group influenced by the U.S. planning firm of Harland Bartholomew and Associates was advocating for the planning and zoning of land to be led by infrastructure; that is, residential development should only follow the building of schools, parks, water services, and so on — a reversal of the usual urban developer grad-and-run model. What could not be ignored, Mansbridge contends diplomatically, was that it was an exclusively ownership-driven view of development. Bluntly, renters were not encouraged.

This was believed to ensure social and civic stability.

Nor was economic development encouraged to any great degree. It remained spotty with some timber extraction and milling, along with the Great Northern Cannery at Ambleside that survived until 1967. Land development and increasingly more sophisticated forms of architectural design would renew themselves as West Vancouver’s economic engines.

Since 95 percent of the district was residential single-family, adjustments in the status quo were inevitable. Larger lots would now be sited further uphill on the slopes. Duplex and lodging units would be permitted only along the shoreline areas. Interestingly enough, minimum 200’ super-sized frontages were zoned for the British Properties north of the Upper Levels Highway. A maximum line of development restriction was also placed at 1,000’ above sea level and this has withstood the pressures of time, ensuring the survival of the “Green Wall” along the mountainsides. This enforcement has been maintained by consistent municipal refusal to provide water services higher than the thousand-foot line.

Whatever the leading design principal, the book’s narrative emphasizes how landscape here has continued to contour West Vancouver’s street patterns. In terms of architectural vision, the leafy charm of Francis Caulfield’s original vision of individualistic homes was bound to rub against Leyland’s later commitment to “bigger is beautiful,” as personified by the British Properties. Mansbridge assesses the two contending views and notes insightfully that Caulfield planned his development before common automobile use. British Properties’ showy American Dream model simply assumed vehicle ownership. You need wheels here; otherwise, you or the nanny would be compelled to walk all day to buy a quart of milk.

But what of the Rio de Janiero-style apartment towers that line the shores of English Bay from Ambleside almost to Dundarave? Simply put, by the 1950s a growing local government demand for revenues made a shift in density zoning decisions unavoidable for an aging, low-growth civic polity. With choices limited to an emphasis on either industrial growth or apartment densification, the latter won out. When the towers arrived, they were restricted to twenty storeys; even so, they dwarfed the old Ambleside village area where family vacationers had once tented.

Dreamers and Designers reports how community activism in the late 1960s fought back against repeated massive redevelopment proposals in the waterfront areas, including a huge project idea from Jack Poole, and this led to the West Vancouver Preservation Society, the first of dedicated issue voter alliances. Since then, density has more or less been confined to the “downtown” Marine Drive corridor around Ambleside. As the book veers steadily toward more detailed discussion of architectural designs within the residential housing field, the issue of “monster” home construction that raised its head following EXPO ’86 also surfaces. Subsequently, long eerie stretches of the British Properties became in effect “stuccoed wastelands” with sprawling cakebox-design homes appearing more like mid-sized apartment blocks set atop Allan block retaining walls.

Nearing contemporary times, the steadily transforming ethnic makeup of the district is given necessary attention, its Iranian and Chinese communities most notably. Mansbridge rightly observes too, that historically the Squamish First Nation rightly should have had a larger say in local development issues. Until recently, he argues, they were instead regarded as more of a hindrance. Yet despite being plundered by both government and business from early contact periods onward, they have endeavoured to assert their rights. From 1970 onward they have litigated, and their challenges have resulted in the return of several major blocks of land to Squamish F.N. jurisdiction, including the return in 1983 of exceptionally valuable shorelands south of the Park Royal Shopping Centre. They have now become a major player in the District of West Vancouver’s future.

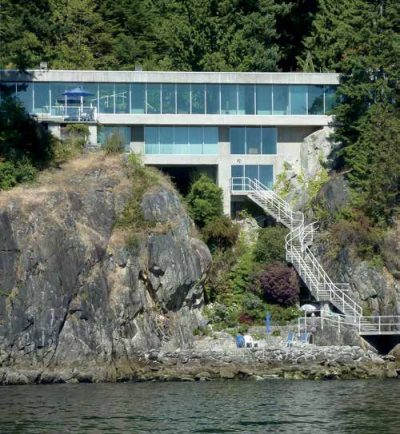

Among the book’s strongest qualities are the photographs, both archival and those by John Moir. An eight-page colour section features a series of character design homes of the Vancouver Magazine and Western Living variety. Perhaps more attention could have been given to West Vancouver’s cultural history — Lawren Harris, James Clavell, Alice Munro, Douglas Coupland, Terry Jacks, and a flock of others are associated with West Vancouver, but in fairness the book does not purport to be a history per se. Rather it’s about the nature of its built form and how all this came to pass. Within that discussion, there’s history aplenty, as well as deep gossipy information suitable for sharing with friends.

After Daniel Francis’s recent worthy history of the District of North Vancouver — Where Mountains Meet The Sea: An Illustrated History (Harbour Publishing, 2016), The Ormsby Review #107, March 22, 2017 — this edition by Francis Mansbridge makes a natural bookend for readers keen to learn more about the development of the communities so favourably situated along the North Shore of English Bay and Burrard Inlet.

*

Trevor Carolan writes from Deep Cove, North Vancouver, where he served as an elected councillor between 1996 and 1999.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.