#435 Northwest Passage for mariners

Rowing the Northwest Passage: Adventure, Fear, and Awe in a Rising Sea

by Kevin Vallely

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2017

$24.95 / 9781771641340

*

Canada’s Arctic: A Guide to Adventure Through the Northwest Passage

by Ken Burton

Delta: Pacific Marine Publishing, 2018

$49.95 / 9780919317581

*

A joint review by Christopher Wright

First published Nov. 30, 2018

*

Here are two books with the Northwest Passage squarely in their titles, although, in a sense, neither is really about the route. It may be that reference to the passage is permitted by journalistic licence, as an article in the current issue of Maritime Magazine is headed “An Awesome Pleasure Craft Journey in the Northwest Passage,” yet the second paragraph makes it clear that the passage wasn’t even attempted due to ice conditions.

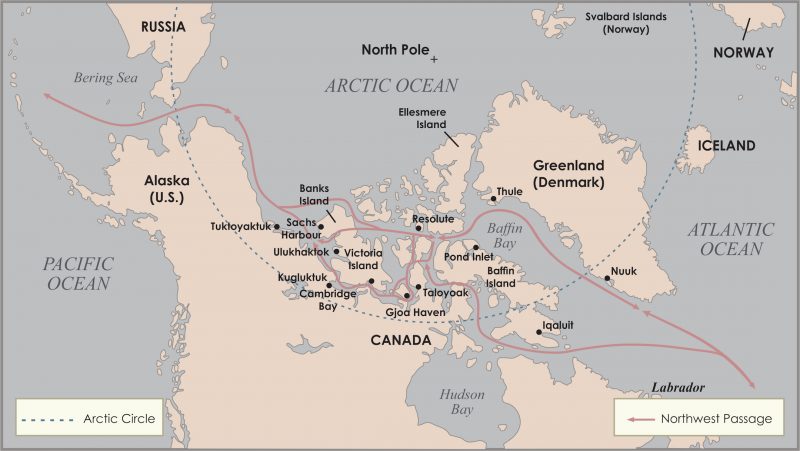

So what is the Northwest Passage? First and foremost, it is a transit from Atlantic to Pacific, or vice versa through the Canadian Arctic archipelago. In undertaking the passage, a craft may use one of seven routes, or a combination thereof as shown on the map below.

Turning first to Kevin Vallely’s book, Rowing the Northwest Passage: Adventure, Fear, and Awe in a Rising Sea, four rowers made up the Last First Expedition and were Kevin Vallely, author and adventurer; Paul Gleeson, who had rowed the Atlantic in 2006; Denis Barnett, Paul’s friend who was looking for an adventure; and Frank Wolf, with fourteen major adventures to his name, many by canoe.

The four intended to row from Inuvik to Pond Inlet in a single season, and while it was partly to be an expedition, the trip was also intended to draw attention to climate change in the Arctic. Their primary sponsor — Mainstream Alternative Energy from Eire and its CEO Eddie O’Connor — are advocates for minimizing the impacts of climate change, and so it seemed like an excellent match.

However, the book doesn’t seem quite sure what it is about. The title is all about adventure, and a good bit of the text is about their trials and tribulations in making progress. Vallely writes well about their progress, or lack thereof; as well as the impact of climate change, weaving in testimony from old timers; observations about local conditions; and a bit of science. The book is both cogent and articulate about what is happening, and who is being affected.

Unfortunately, many people may overlook Rowing the Northwest Passage because they aren’t really looking to read about a rowing adventure in the Arctic, and they may not realize how good it is about climate change.

The Vallely foursome didn’t make it to Pond Inlet, stopping short at Cambridge Bay. The main reasons were stormy weather, high winds, and concern about ice. Stormy weather is a function of climate change, although the link wasn’t made. Also, ice conditions weren’t as bad as suggested in the book, and a full transit was quite feasible. Twelve adventurers, four mega yachts, three cruise ships, and the bulk carrier Nordic Orion all made it through the Northwest Passage in 2013.

Technically, the trip was achievable. Pond Inlet is between 920 and 950 nautical miles from Inuvik, depending on the route. Based on a modest ten nautical miles per day, it could have been achieved in a 90-day season. Apparently they had expected to average thirty miles per day, and hoped to do much more. As Charles Hedrich (a French Adventurer) also found, weather makes the difference between what is planned and what can be achieved. His solo row through the Northwest Passage took three seasons, 2013, 2014, and 2015.

Another factor may well have been weight. The Arctic Joule, stuffed with supplies for four including a lot of electronics, was a husky 2,600 lbs, while Hedrich’s boat — Rowing Ice — weighed only 190kg empty; yet at seven metres long, it was only slightly shorter than The Arctic Joule. Vallely comments that the boat was designed to take punishment from the ice, hence its weight, but that weight came with a price.

Another factor may have been basic hydrodynamics. An important factor in overall propulsive efficiency is the length-to-breadth ratio of any craft. Most ocean rowboats seem to be on the fat side with a length-to-breadth ratio of between 4/5 and 5. However, The Arctic Joule seems to have been a remarkable 3.2/1. Another puzzling factor is that between Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk they lost time because they had to drag the boat over sandbars. They had an electronic navigation system, and there are three electronic charts available for the route, but they did not seem to follow the channel.

Despite this uncertainty, Rowing the Northwest Passage is a good read and brings home the impact of climate change on the Arctic. Illustrated with a few photographs in the middle, it really could have used a map showing the rowers’ route. It is often said that distances in the Arctic can be deceiving. Vallely notes that the group rowed 1,163 nautical miles in 54 days. While it is obvious that they ended up making some significant deviations, like the visit to Paulatuk, this distance seems excessive compared with the direct sailing distance from Inuvik to Cambridge Bay, which is 759 nautical miles. A map showing the route they took would have been helpful in understanding why they rowed so far.

*

Mapping is not an issue with Ken Burton’s Canada’s Arctic: A Guide to Adventure Through the Northwest Passage. It is profusely illustrated from start to finish, printed on heavy gloss stock with many maps and great photographs. It is an excellent guide to the Arctic for the armchair traveller, the adventurer, and the cruise ship guest. While nominally about the Northwest Passage, it really traces the Arctic portion of Burton’s trip in 2000 with the RCMP catamaran Nadon, which was temporarily renamed St Roch II for the voyage.

In fact, Canada’s Arctic may have been published to coincide with the ninetieth anniversary of the construction of the original St Roch, which occurs this year (2018). Reference is also made to the Crystal Serenity trips in 2016 and 2017, where Burton served on board as an historian for Crystal’s guest enrichment programme. Burton also mentions a trip he made with the Akademik Sergey Vavilov with One Ocean Expeditions, and he gives credit to One Ocean in the prologue.

Canada’s Arctic is organized into four sections. Part 1 is an introduction and history with good coverage of the Franklin Expedition and the discovery of the Erebus (2014) and Terror (2016) shipwrecks. In this respect it might have been appropriate to recognize that the Terror was found courtesy of Inuit oral histories that had been ignored for decades, and the more recent advice of the Inuit hunter, Sammy Kogvik.

Part 2 covers the western approaches from the Bering Sea and Alaskan communities up to Point Barrow, and in Canada as far as the Bellot Strait. Perhaps because two communities in the Western Arctic, Sachs Harbour and Paulatuk, were not visited, no details are provided; and they are also missing from the main map about the trip.

Part 3 takes the traveller through the heart of the Northwest Passage to Pond Inlet. Part 4, which is not a part of the Northwest Passage, follows the route of St Roch II from Pond Inlet to Iqaluit.

Pond Inlet receives extensive coverage and obviously benefits from a recent visit, although it is not a centre for mining in North Baffin, as Burton asserts, that being Milne Inlet where Baffinland Iron Mines have their base and ship loaders. Also, apropos Qikiqtarjuaq, Burton mentions the Sabellum Company and its whaling activities. Sabellum was always a trading company until it collapsed in 1926 due to public opprobrium over treatment of their sole English trader. It should also be noted that whaling in the Western Arctic did not commence until the 19th century, after the whaler Orca returned with a good haul of bone and oil in 1888.

Canada’s Arctic will no doubt find its way on board many ships visiting the Canadian Arctic, whether or not they are on a Northwest Passage transit. It will also be helpful as a guide to adventurers who are contemplating a visit, with practical guidelines about polar bears and Burton’s best practice about conduct in Inuit villages. It would be helpful to know whether the guidelines he provides echo those by the Association of Expedition Cruise Operators, to which One Ocean belongs.

In his community descriptions, Burton has an unfortunate practice of referring to the local supermarket as the “Co-Op.” While some communities do have a Co-Op, most have a Northern Store, or Northmart, and some — like Cambridge Bay and Iqaluit — have both. Burton’s comments about regulation are inappropriate, and he doesn’t mention the Arctic Shipping Pollution Prevention Regulations, which have been in place since the early 1970s. In controlling access to the Arctic, Canada has to walk a fine line with regulation, as the US and other maritime nations claim that the Northwest Passage is an international waterway, while Canada asserts that it is internal waters.

Burton’s statement that the Canadian Coast Guard open and close the Arctic at the beginning and end of the season is erroneous, as is his comment that Grise Fjord does not receive maritime service. The Government of Nunavut ensures that all Arctic communities receive at least one re-supply call each season for dry goods and fuel. In 2017, the community received dry cargo calls by NEAS Avataq, Desgagnes’ Camilla Desgagnes, and Coastal Shipping’s Havelstern for fuel.

Having been part of the staff for Crystal Serenity in 2016, Burton might have supplied accurate figures for passenger and crew numbers. For the record, in 2016 there were 1,619 Persons on Board, assuming Crystal’s official figure of 655 crew gives a passenger complement of 964, not over 1,000. In 2017, the Persons on Board figure was 1,319, with 664 passengers.

Burton also implies that the transit was solo and unsupported; but it wasn’t. Crystal chartered the RRS Ernest Shackleton from the British Antarctic Survey to join the Crystal Serenity at Ulukhaktok and escort her through the Northwest Passage to Pond Inlet. The Shackleton is an Antarctic logistics ship and carried survival kits for passengers in the event of a serious incident. She also embarked two helicopters, seventeen zodiacs, and fifteen kayaks for passenger community visits and sightseeing.

Despite some inaccuracies, Canada’s Arctic is valuable in that it covers most communities in the Northwest Passage as well as many locations in the Eastern Arctic outside of a normal passage itinerary. Despite a regrettable number of errors and a need for better editing, which could have caught unfortunate spelling mistakes and duplications, this is an excellent book about the Arctic and well worth purchasing.

*

Christopher Wright is the retired President of The Mariport Group Ltd., a specialized marine and port consulting company formed in 1989. On his retirement in 2013 he joined WorleyParsons Canada (now Advisian) in a contract position as a Marine Logistics Specialist. In 2016, he published Arctic Cargo: A History of Marine Transportation in Canada’s North (ISBN 9780995252509). Marine activity in the North has been poorly documented and Arctic Cargo now provides an indispensable and timely guide. Christopher maintains a web site concerned with Canadian Arctic History at <http://www.arcticcargo.ca/> He is currently working on a new book, to be published in 2020, on the history of polar cruising. Christopher Wright lives in Digby, Nova Scotia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster