#431 The Spider Hunters

MEMOIR: The Spider Hunters

by Lee Reid

First published Nov. 23, 2018

*

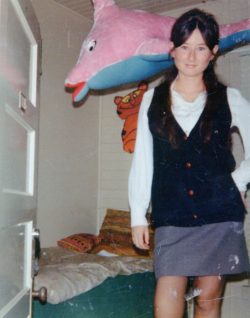

We are pleased to present The Spider Hunters, a coming-of-age memoir by Lee Reid (née Batchelor) of her early life in England (1946-1952), and then on densely-forested and thinly-populated Curteis Point near Sidney, Vancouver Island, between 1952 and 1964.

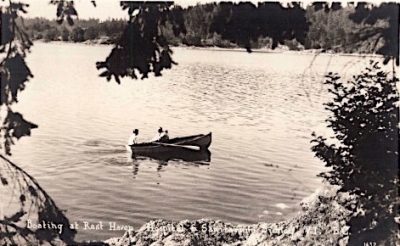

The Spider Hunters extends from rural England to backwoods and small town Canada; from a Catholic girls’ school in the west of England to Curteis Point — pronounced Curtis — where Lee’s neighbours included well-known BC writers Muriel “Capi” Blanchet and Raymond (R.M.) Patterson, trailblazing BC publisher Gray Campbell, and an assortment of retired navy, army, and air force officers recovering from two world wars.

The Spider Hunters is Lee Reid’s story of surviving a shattered military family in a postwar setting and finding solace and support in elders, nature, and education. – Richard Mackie, editor.

*

The Spider Hunters

Like millions of orphans and refugees, having no home was normal to me. Some of us are born that way. We wander around the earth like tough little turtles without our shells. And every homeless step feels like life or death. Children don’t grieve what they never had, until time or old age demand that they do.

Since I was a wee child, “home” did not mean the world I saw around me. Home was a place without walls, my secret fantasy world. I assumed that perhaps the dead or the crazy people understood the reality of invisible places, but nobody I knew in the late 1940s and 50s mentioned imaginary worlds. In my England of 1946, where I was born just after the War, people were preoccupied with survival matters: food rationing, getting enough petrol, and rebuilding from the ruins.

After years of German bombing raids on the English cities, people craved the ordinary, the day-to-day routines: school, tea, church, shopping, chatting with neighbours, all culminating in Sunday dinners with the remaining old folks. Meals were simple: canned peas, canned milk, and kippers or corned beef.

My Canadian father was stationed with an RAF base in Wiltshire, and we lived nearby on a farm in Somerset. When my younger sister and I were five and four, we were sent to a religious day-school in Somerset, Saint Elizabeth’s Academy for Girls. It was regulated by kindly, sombre nuns in black habits.

Their peaked hoods and dark robes reminded me of black ravens who cawed mournful prayers regularly throughout our days to save our sinful little souls. God, whom they believed to arrive through prayer, would send the flock into a royal flap. I felt mesmerised at the vista of robes rising like huge wings as the nuns genuflected, their inky shadows and long pallid hands fluttering gracefully to the ground when they prostrated in prayer. I wondered if nuns wore underwear, like regular people. I was always curious about what hid behind the polite habits of adults.

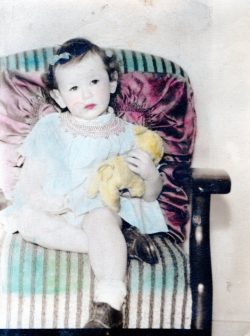

On school mornings, our father woke us when it was still dark outside. He helped us into our scratchy brown uniforms with the blue ties, short pleated skirts, itchy brown woollen underpants, and brown knee socks. He combed our hair, tenderly washed our sleepy faces, and then he cooked our breakfast. My short hair was a knotty tangle of dark curls, impossible to cut with a comb. My sister had silky straight red hair that I envied for her ease with ponytails and pigtails. She was adorable, with large honey brown eyes set in a heart shaped face. I, the taller boney one who resembled our father, was nicknamed “the Tartar” because of my slanting hazel eyes, high cheekbones, larger bones, and angular features. Unlike my father, I looked like a native from Tibet. My sister had peachy cream skin and tiny bird bones like our mother. My skin was sallow and pale, but we both shared freckles.

Our father would cook us hot porridge smothered in brown sugar and cream from the farm. While daylight awakened the countryside, our kitchen with the oil stove bellowing smelly heat felt warm and comforting in our father’s calm presence. “Shhh,” he cautioned, “Your mother needs her sleep,” as though mother was too fragile to face life. Mornings were not her time. Mother, who was a petite lady from a rich Irish-American family, had not mastered the art of domestic skills. Nor did she seem to enjoy children.

Our father would walk slowly with us up the green country driveway, where bird trills and fragrant springtime blossoms welcomed our day. Gently he held our small hands, pausing at times for us all to savour the chartreuse and amber leaves gilding the trees. I wanted the intimacy of our morning walks together to last forever. I knew it would end at the main road, overshadowed with rows of old trees which would show us the way to school. My sister and I would toddle off on our own to school like baby ducks without their mother. There were few cars about, since people could not afford petrol.

Off to work each day went our father to some mysterious place named Hullavington Airbase where men flew planes on dangerous missions over Europe. For us, the war did not seem to be over. Each day held a flavour of uncertainty. Each day I expected him never to come home. At night, I felt enormous relief when he did. For another fleeting day, he was mine.

The only thing that I liked about Catholic school were lunches served in a dining hall by the nuns: quivering jellos in ruby reds and lime greens, glasses of sparkling apple juice with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and, best of all, stewed gooseberries with thick custard cream. To this day, gooseberries are my favourite treat. I associate them with those mornings and walks, when my father anchored our home.

At school, I soon decided that God and the rules were dumb. Although I was only five, I failed as a good little Catholic girl. I was bored, and I resented being treated like a stupid sheep. I hated prayers because they all informed me that there was something terribly wrong with me. I was told that only obedience, prayer, and God could fix me. I liked arithmetic because my father said I was good at it. I lost my aptitude for numbers right after his death.

My little sister was a trusting child who obligingly followed me around, although I was the troublemaker. I was not kind to her, because everyone liked her and not me. I knew I was not loveable, but at least I could add, subtract, and rebel. I took to running away, towing little sister along on her short legs like a pudgy puppy. This was fun, especially when the nuns would squawk and fly around in all directions. They were not punishing, which made me more contemptuous and rude. They tried bribing us with shiny things to stay in school: smooth medallions and fake statues of Mary and the Saints. Of course I gleefully escaped even more, thus earning a large stash of religious relics. Running away was my first taste of power, and getting paid to do it was my first job. It seemed to me that rebellion might be more rewarding than being a good girl, or at least I was better at it.

Except for the nuns’ reactions to my school rebellions, we kids were invisible. We had a physical home, place, people, and country, but I didn’t fit. If I could title those young years, our unsettled Air force family would be named “desperately seeking normal,” and I would be the “defiant restless kid with huge ears.” “Be thankful for what you’ve got,” my sister and I were told by most adults, and “children should be seen but not heard.” In retaliation, my sister, who was usually a caring and sweet redhead, threw the occasional angry tantrum. Nobody could calm her flailing little body, which boiled and howled like a formidable red tornado, far brighter than her hair. She was inconsolable as much as outraged at being neglected. I just went off on my own, though nobody noticed. In differing ways, my sister and I determined very early that freedom was more attractive than our home in England.

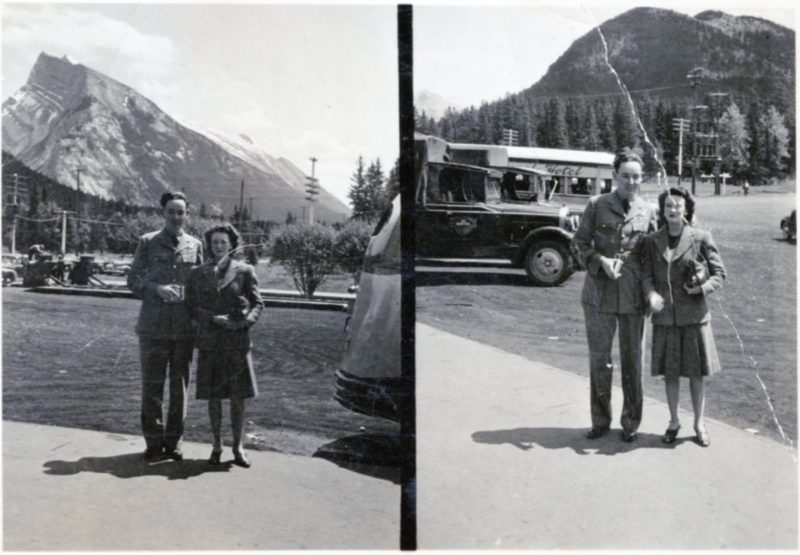

We belonged to a peripatetic postwar RCAF/ RAF family. Every year, my sensitive and ethical Canadian father, who had been a combat navigator during the war, was posted to a different air base in England or Canada, where he trained young pilots to fly. I adored him. Our mother Dorette adored him. We seldom saw him and, although we saw more of our mother, we never discovered who she really was. She kept so many secrets. My sister barely remembers our father, yet she still misses him. Somehow, we both knew he loved us with the tender desperation of a doomed man.

I had no chance to put down roots. Most people dig their feet into land at some point and say “Thank God I am home. This is where I stay.” But I could not physically settle. My little body seemed forever on the run. Whatever home was, I wanted it, yet I rejected it. This wasn’t sad for me; rather, I felt intrigued and curious about the unknowns and unseens that created what I saw as a not-home. Freedom meant that it was convenient for me not to be noticed by the adults. In return, I took a lonely command of my life. In those days, parents did not play with children. We were managed with proper English nannies, or sent off to occupy ourselves around the farm.

Both my sister and I do remember being held securely in our tall father’s lap in the evenings, each one of us balanced on his strong knees. We remember the scrumptious red liquorice Twizzlers he always brought home for us to chew, and the shrieking thrills we felt as we flung ourselves gaily up into his arms to be lifted far above his head. We trusted his capable hands not to drop us, not ever. In particular, I remember the sweet aroma of his old cherry wood pipe, which he smoked while cuddling us in his arms before bedtime. To this day, I still love strawberry Twizzlers, and I instinctively brighten at the rare sight of men smoking their pipes, the smoke looping in halos above their heads.

I recall that last summer in Somerset in 1951. We had rented the top half of a farmhouse, a meadowy farm populated with laughing pigs, giggling chickens, and smiling dairy cows. All the animals looked happy. They had friends, family, and home, or so I thought. I, on the other hand, could feel that a war had recently been fought at enormous cost to the land and the people. I felt a blackness in the adults. A heavy weight shrouded them and so I crept around quietly and stayed out of their way. I knew that I had barely survived my birth in a bombed hospital in Darlington in January 1946, and I knew with irrevocable dread that my father would soon die. Was I happy? No, I was watchful.

On weekend mornings at the farm, I would stroll past the pigpens where I imagined the pigs partying in snoutfulls of warm mud. My short wiry legs took me through English meadows blue with Canterbury bells as tall as I was, through pastures where I called cheery “hellos” to the brown sugar cows contentedly chewing on clover blossoms.

Each morning, I aimed my scuffed English penny loafers beyond the edges of the farm and into the woods where lived my magic pond. There I would sit for hours with the frogs murmuring around me, hidden among the willows and lilies on the banks. I remember gazing deeply into the pond like a crystal ball, my eyes following filters of light into the mysterious depths while my senses floated like dragonflies on its shimmery ripples. What hid at the bottom? Did translucent fish live in the silvery darkness? Was there a world below my world, calling to me? My short life felt fluid and unsettled, with no solid ground to root in. I could float on it, but I could never swim in it.

*

In February 1952, my father was killed on a training flight over France. The morning he left, I felt “today you will die.” We both knew this with a recognition more tragic and inevitable than sadness. He understood fate; it was his end time. He had survived numerous missions during the war. His airplanes had suffered more explosions and bullets than machines or men could possibly endure, but peacetime brought death. I saw all this in his face, and more. I saw love, I saw grief, and I saw regret and fear for what the future would hold for his children, particularly without him to protect us. At the end of that day, there would be no relief to hear him call, “Hello poppets, Daddy is home.” He was 32.

The plane crashed in the Alps. Six crewmen died fast and violently, high in the frozen mountains of Languedoc. This was never discussed, never consoled, although Mother now slept all day and the nanny managed our hours. Before long, Mother determined that we would go to my father’s family, in Victoria, B.C., Canada. She never told us why she steered clear of her well-off Irish and English relatives in Cleveland, Ohio, where her only brother (Robert Beaumont) lived, or why she rejected her own father and an assortment of aunties in England. My father’s family were hardy Saskatchewan farming stock, fundamentalist Baptists and devout Catholics. She had nothing in common with them.

Abruptly, we left the farm, the happy animals, and my magic pond. My sister and I were in a daze. I recall a long drive with my reserved English grandfather, Reggie (Reginald Sylvestre) Beaumont (1890-1968) and my withdrawn American mother through the dark countryside.

Then my mother, sister, and I set sail for Montreal. I was just six when we caught the Queen Elizabeth from Liverpool. Throughout the voyage, Mother and my sister were sick with migraine headaches. They stuck to their bunks. I rode the elevators by myself to the dining hall or prowled the corridors. It must have seemed odd to see a tiny girl roving the ship on her own, a child who said “Yes, please” and “Thank you, sir,” with a precise English accent.

Our shaggy sheepdog Blackie was crated in the hold. I missed her; I worried she would be lonely and scared. I trekked by myself down to the hold to pat her during visiting hours for pets. What I did not know was that my sister also roved the ship and rode the elevators, despite her headaches. I wonder how we missed finding each other? We could not guess that there would be many misses throughout our lives or that we shared more mutual damage than was apparent. Sometimes we did visit Blackie together, and we learned the word “quarantine” meant that Blackie had to be isolated. My sister and I felt just like Blackie.

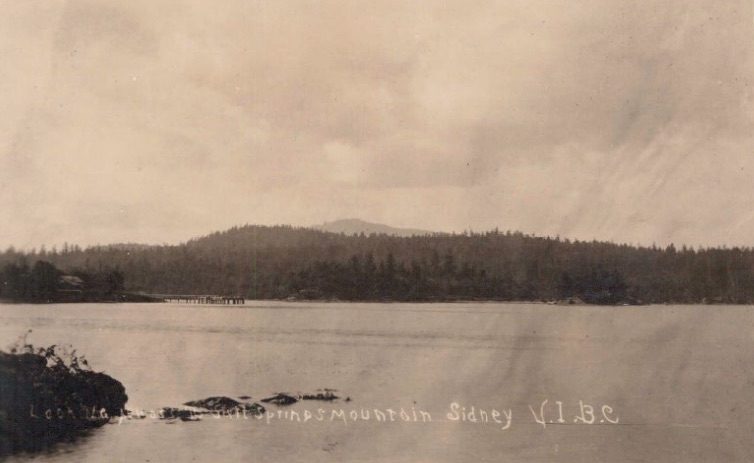

Sidney, Vancouver Island, 1952

In Canada, we caught the train from Montreal to Vancouver. I remember getting lost in a crush of milling grownups at the Montreal station. Panicked, I looked for my mother and sister but I was minuscule among the waves of big people. I turned back towards where I had last seen my family and flung myself against the crowd, squeezing through cracks between large bulky bodies until, luckily, I spotted them through a gap. Mother hadn’t noticed I was missing. “Oh, there you are,” she said with a frown. I was silent. My loyal sister grabbed my hand. She would not leave me. She never has.

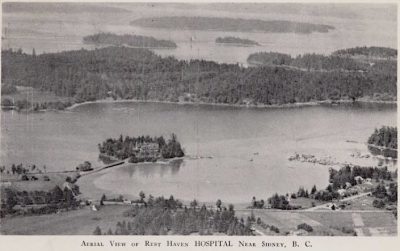

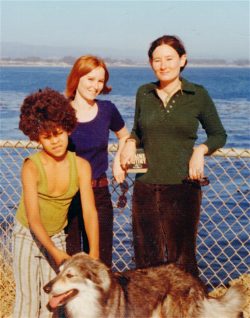

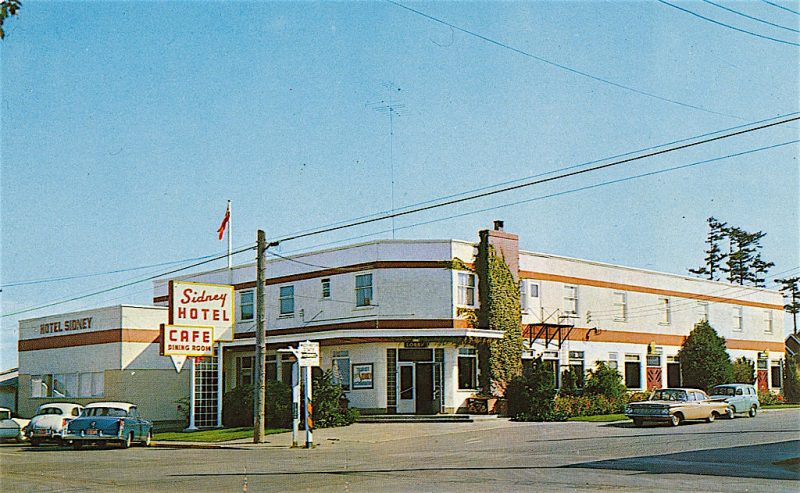

Near Sidney, a quaint village on southern Vancouver Island, we settled into our new life on the ocean at Curteis Point, a life of stormy cliffs and untamed forest, where my sister and I ran wild in the woods while the grownups partied. Our widowed young mother dyed her dark hair red and launched into her career of drinking at the Legion on Mills Road, the Army, Navy, and Air Force Veterans pub on 4th Street, and the Sidney Hotel pub. Dorette must have been thirty at the time. With her expressive brown eyes, intelligent delicate face, and petite yet full figure, she could be the charming and vivacious centre of male attention. Some admirers called her “Dixie” because she was a Yank. Before long, she married an older war hero from the First World War, a retired RAF Air Commodore named Sidney Leo Gregory Pope (1898-1980). Everyone called our rollicking Irish stepfather “Poppy” or “Poppy Pope.”

Poppy was a charismatic popular Irishman, towering at 6 foot 6. He charmed everyone with his endless repertoire of war stories and jokes that evaporated into red faced giggles, waggling fingers, and smirks when we kids came around. The town equated Poppy with good times. We could always locate him by the roars of laughter in the back rooms of the shops and businesses along Beacon Avenue. He was funny and adventuresome, always with drinks at hand for visitors and clients. He ran Sidney Real Estate, which seemed successful enough. A lot of people trusted him to invest their savings in land. Our tiny and lovely mother with the veteran’s pension also appeared to be a good catch for Poppy, who was a widower. I think that both of them assumed the other had lots of money and station to keep them in parties and liquor.

My sister and I watched Poppy’s daredevil shenanigans with amazement and awe. With a drink in one hand, he would collect bets, then rip off his clothes, jump from the cliffs into the ocean, and swim across the bay to Sidney; or suddenly, on a whim, take us all boating on a friend’s yacht or spontaneously pile us into the lumbering old Monarch for skiing trips up-Island to the Forbidden Plateau. Once launched, the adults ignored us, of course. Poppy was the life of every party and quite the flirt with women. I could see that this hurt and enraged our mother, although she too depended upon the attentions of men. Drunken rages ensued. The interventions came from my sister and me, who would stand defiantly between the warring adults to protect our sobbing mother. “Go away, you leave her alone, you bastard,” we yelled at Poppy. I realised that the war in England did not seem to be over in Canada.

My sister and I roamed the town together. We pelted down Beacon Avenue to where the barely paved main street ended at the Sidney wharf. There we could check out the googly-eyed fishing catch: salmon, cod, red snapper, even crabs, all laid out in dead shiny rows, like silver coins under ice. Their fishy stares reminded me of the old people drinking at the bar. We lay on our stomachs to count schools of transparent jellyfish undulating under the wharf; we wondered if the giant purple and orange starfish who hung there would ever catch them. Could anything hold on to globs of jelly? Nobody could hold on to my sister and me; we easily slithered away from grownups. Suspended from the creosote pilings, we saw pale sea cucumbers with flower faces that breathed like fish underwater.

We usually ended up at the Choclit Shoppe for ice cream cones or at Cornish’s bookstore where we read all the Archie comics. I got hold of every book I could read about fighter pilots at war or aviator heroes. At the time, I had no idea why.

We were trained to be polite children but I, in particular, despised drinkers. There were slurred fights and quarrels around us. “How stupid,” I thought. We slid around it all with a wary and cunning contempt. Nobody dared touch us cheeky ragamuffins. Late on school nights we would get fed up. “Take us home, Mum,” we commanded, angrily hauling our mother away from the bar. Although my sister was firm with her in a protective and kind way, I hated our mother and I exuded contempt. My sister looked petite like our mother; she was her pet. I remember Mother holding my sister on her lap when my sister had headaches, or asking her to fetch her tea and coffee, like the maid. I despised our mother’s weakness. I was not kind about it. I was too young to realise that perhaps she might have felt as homeless as her children.

*

At Curteis Point, fierce storms howled in from the ocean while shrieking winds shredded the moon. The ocean felt frighteningly beautiful to my sister and me, and more of a haven than the bars. We knew the ocean could kill us, but we loved it and we lived on it. In our leaky rowboat, we explored the shores and islets, digging for clams, crab, and oysters. Nobody bothered about lifejackets for kids.

The storms felt oddly human compared to the onset of our mother’s cold silences and rages. The storms touched us and moved past, unlike our mother who froze us out with a thick wall of ice. I silently wondered what horrible sin we had committed to so offend her, but of course we never talked about it. The Pacific gales shook our house to the foundations.

We lived in a flimsy 1940s shack built by Poppy on Curteis Point, near the Swartz Bay ferry. Back then, the Point had few homes or people. It was covered with forests that culminated in steep cliffs plunging to rocky beaches and the ocean. Tryon Road wound around the Point to connect us with the Pat Bay highway, the ferries, Sidney, and Victoria. The highway itself was little more than an asphalt two-lane country road. Near the ferry, the yellow school bus would pick us up, but we had to walk fifteen minutes each way to reach it. Sometimes we just rode our bikes to school, which was ten miles away.

In the 1940s, before we arrived, people accessed the Point by boat. There was not yet a through road. It still felt isolated to us. Our shack clung to the cliffs like the sinewy arbutus trees anchored around us in steep rocks. Their graceful orange trunks leaned sideways into the winds with a hallelujah that defied gravity. I felt like an arbutus, digging nourishment from my granite home.

Despite her delicate appearance, our mother could be as tough as an arbutus. She made sure she always got her own way. To punish or blackmail people, she would erupt with hysteria. We kids learned to watch out for her dramas, to get out of the way. “So how is she tonight?” we would check with each other in low voices, collaborating for once to get the latest emotional weather report. If “she” was stormy drunk, we would sneak into the house through the bathroom window and slide down the basement steps to our bedroom. There, we resumed our separate lives while our mother prowled and raged like a black widow spider above our heads.

Our mother, who was a bit of a hoarder, would not let go of anything. The house and her bedroom accumulated years of memorabilia and clothing from the war. She also tackled “the Government” to demand that they reinstate her RCAF widow’s pension when Poppy left her. Although it took her years and a divorce, she won. She was a survivor and a fighter. People began to avoid her — and us.

My sister and I shared, or rather divided up, a cold basement bedroom where we fought over our single source of heat, an electric radiator. We were not alone. Our bedroom was populated with gigantic but friendly black spiders. Like acrobats, they hung upside down from the ceiling and walls. Our nightly routine consisted of spider hunting. To navigate a clear path to our bedroom, we grabbed our slender fishing rods as we descended the basement steps, squashing the spiders with our wands all the way down to bed. Their bodies hung dolefully from the ceiling like hairy pockmarks on the moon. Mornings, I often had the uncomfortable feeling that spiders had kissed my face. Unlike our mother, they never bit us.

Life on the primal ocean was not peaceful or pastoral like England, but our freedom gave us a feeling of home. Or was it the joy of rebellion? The rugged landscape felt good to me, a welcome reprieve from the regulations and rules of England.

My sister and I became Warrior Queens. “What will we do today?” was our call to fun adventures. We had command of the beach, the forests, the cliffs, the sea creatures, and the water. All day we ran, built forts, waded, swam, or rowed our skiff with Paddy, our sturdy black Labrador, paddling mightily behind us. Blackie, who was too old for adventures, stayed home to offer company or comfort to our mother.

We scaled the cliffs and made homes in the caves. Around Curteis Point, we flew and swooped our bikes like airplanes, challenging the hills of the winding road. Crashing off bikes meant nothing compared to our exuberant freedom. My imaginary world enlarged to become the heroic battle of Light against Dark. I populated my warring empire with immortal fairies and elves who opposed death and the grownup world. I resolved never to grow up, and I always kept moving. That was how I discovered the hidden glade.

I had no idea why, that spring day, I just had to scale the cliffs at Patterson hill, then push on through the dark woods that probably belonged to the nearby estate of Captain James Douglas Prentice, another war hero of the North Atlantic run. Perhaps I was tired of the daily war zones at home. Although I was only nine or ten, I decided to slog through a swamp of stinky skunk cabbages and bushwhack my way under fallen trees covered with scratchy lichens, heading into the heart of a pretend jungle. Perhaps it was the warm tang of April earth melting mauve patches of snow, or the aura of light that seemed to glow beneath the thick moss carpet under my sneakers, that propelled me forward. It was tough going. Sinewy arbutus forced me to bend sideways, crawl beneath their crimson branches where the bark peeled back to reveal pale skin. When the forest suddenly yielded, I sprawled into a glade quivering with white lilies. They sprang from the moss in ivory wands dusted yellow with pollen. Sunlight poured like liqueur into the glade where hundreds of lilies lifted chalice cups. Cherished by lilies, I lay deep in the moss. Hours passed, but I was floating outside time.

From that day on, I could never predict whether or not I would find the lily sanctuary again. The forest persisted in closing around it, as though it needed protection. In later years, most of the woods were bulldozed for development.

Homes Away From Home

When not in battle, my sister and I created fairy tidal pools on the beach, which we populated with pink shells and snow white quartz pebbles. We adopted imaginary seahorses and made barnacle castles for tiny crabs that glowed like pale ghosts underwater. They became our families. We talked to them as if they were our babies. “Don’t worry, we’ll protect you, nothing will eat you,” we assured them, as we swatted fiercely at the seagulls and crows or fought off the invisible forces of evil that blew in with the winds.

For our pond we gathered up orphan periwinkles, those delicate snails whose lacy feelers crept tentatively across smooth rocks looking for shelter in the cracks. We knew what it felt like to grope for shelter. Sometimes, pinkish minnows with deer-like eyes glided past and the fragile crabs waved tiny claws that suckled our fingertips. To the pond dwellers looking up, our child faces must have seemed like two golden moons trailing their straggly kelp hair through the water. Home in nature was as exquisitely unpredictable as the ocean.

Our home-away-from home was also the bar. We hung around the bars and lounges of the Legion and the Army, Navy, and Air Force hall, where the adults drank their way back from battle and re-fought the great World Wars each night. Soon we could easily recognize the slimy grey energy of lies and cover-ups. We could feel the emotions squashed down in the adults, but we didn’t know how to translate it or what to do about it back then. It was a sensitivity far in advance of the times, and it often felt to us like an unpleasant nausea or dizziness. Years later in my counselling career that sensitivity became an invaluable skill for diagnosing hidden trauma.

For meals, we bugged and teased the drunks (as I perceived all adults) to give us money. As soon as we raked in the loot, we ran off to spend it. Pockets jingling with change bought us bags of candy for snacks, lunch, and dinner. We loaded our arms with books from Cornish’s to read for hours in the car while we waited to go home, long after the shops closed. Successfully fleecing drunks became my second paid job in life.

Late nights after the bars closed, and after the War was won and the candy soured in our empty stomachs, mother lurched our 1940s Monarch through the darkness towards home. The North Saanich countryside was lit by warm windows in tidy white cottages that I imagined held love and safety and cozy beds with sleeping children. On those midnight rides, bouncing in back seats without seatbelts, my sister and I would sing “Swanee, how I love ya, how I love ya, my dear old Swanee,” or “Raindrops Falling on my Head” and “Home on the Range.” Through those childhood years in a world of raucous alcoholics, those nights in the car wobbling crookedly towards our spidery bedroom, we entertained ourselves with drinking songs stolen from the adults. I recall singing “Lily Marlene” from the first Great War. “Swanee” probably came from the deep South, where slaves longed for Mother Africa and freedom. So also began this story, a story about all that was and was not home, based on memories that start in England before my father’s death.

In 1958, our stepfather bailed on the family. Poppy embezzled the savings and funds of townspeople who had entrusted him to buy their land. He disappeared, rumour had it, to South Africa, where he set up a Champagne factory. I pictured him drowning in vats of champagne. Good riddance. I felt relieved to see the end of him, although my sister was fond of him. Maybe now, finally, our mother could grow us a home.

Tryon Road in the 1960s

Freedom from Poppy was short-lived. Our mother was penniless, helpless, and depressed. Most women did not work in the 1950s and there was no work except in the service trades. Coming from a background of wealth and title in Ohio, Mother did not have the skills or perseverance to work, and Canada was in a recession. I recall welfare hampers of food arriving at our shack at Christmas, and how relieved we felt. My sister and I took to scrounging food wherever we could, living off the generosity of neighbours. Not everyone was overjoyed to see us come knocking at mealtime. One disapproving neighbour told me to go away and not to play with their children.

When it seemed that nothing could get worse, our mother got pregnant. She lied and told us she was gaining weight. We deduced the father must be Vince, our alcoholic handyman who already had a family of five kids in Victoria. Our mother placed us with Ginger and Speed, a well-meaning boozy airforce couple in town. She disappeared for some months. When she retrieved us her stomach was flat, but she had brought us a new adult friend. Her friend was named Irish. It seemed that home for our mother, who was then in her late thirties, had been reduced to four ingredients: secure a breadwinner; hoard the family silver; obtain liquor to drink all day; and retain a shack in which to live. Compared to her upbringing with maids and cooks, a life without our father must have cut her down in her prime.

Irish came into our lives. We figured out that she had taken our mother to hospital in Victoria and stood by her through the baby’s birth. There was no further mention of what had happened. Years later, we learned that we had a sickly half sibling who was adopted out at birth. Because we heard the baby had fetal alcohol symptoms, my sister and I had no interest in locating it when we got older. Being two orphans was enough for us to deal with.

Around that time, I made three decisions to secure my freedom. They opposed everything my mother represented. 1) Never have children. 2) Get a university education. 3) Don’t drink.

To my hostile young eyes, most women of my mother’s generation looked depressed and resigned. They seemed trapped, even desperate. I figured that motherhood was a miserable fate for women and their kids, all stuck in unhappy homes while also care-taking men who held the power. I knew then that I did not want the life of those women, although I secretly felt jealous of families where the fathers were kind. My womanly choices were limited to becoming a nurse, secretary, housewife, teacher, or alcoholic. I hated those prospects.

How could our mother, a gorgeous, cultured, eloquent, and smart woman have led such an uncreative life? After all, she was the granddaughter of Andrew Patterson, who brought Standard Oil to Europe in 1903. He became a financial advisor to the King of Portugal and was granted the title of Baron, the first and only American to receive a title from Portugal. Alcohol had destroyed Baron Andrew de Patterson’s Irish initiative, and then hers. I decided that a university education might be the only way to protest the legacy dictated by her generation.

It was 1959 and I was turning twelve when Irish arrived to make us a home. What was Irish? The town was as mystified as I was. Irish looked like a big man with cropped brown hair, kind grey eyes, and a deep voice. Irish worked as a clerk at Mitchell and Anderson’s, the hardware store in Sidney. Before that, I remember Irish the taxi driver. There were rumours that Irish had been a logger and a farmer, but the juiciest and nastiest rumours said that Irish was a woman.

I immediately liked Irish. Whatever or whomever Irish was, this person seemed to be wholesome, caring, and devoted to the family. Irish worked hard to support us on a wage of $300 per month. I realised that “home” to Irish meant belonging to a family; and that family, improbably and scandalously for the times, was us.

Irish was a practical down-to-earth Seventh Day Adventist originally from a large prairie family with nine children. Irish had always had a muscular male body and voice as a child, but I discovered her actually to be a reluctant woman. I could see a hint of breasts and hips under her baggy checked shirts and jeans. Although she brought bottles of booze home to please our mother, she was fair and even-keeled until the drinking took hold over the years. Then she got angry. Our mother treated Irish with contempt, like a servant, but leaned on her to make a living and keep her loneliness at bay. In hindsight, I now understand the social harassment that Irish must have endured as she laboured for low wages in rough male jobs, and I appreciate the courage it took to live in a town that rejected unwed mothers or anything different. I heard a rumour that village kids had egged her small cabin and broke the windows before she moved in with us. She was sad about this; not angry, not scared. She was used to mean people.

Adults did not use the word lesbian back then, so this too was not discussed. At age twelve, I was immensely curious about the hidden life of adults. I took to reading secretly the work of D.H. Lawrence, explicit Chinese love stories that I found in the attic, and the Playboy and Star Weekly magazines lying around news and burger joints on Beacon Avenue. I devoured Virginia Woolf and L.M. Montgomery.

Forbidden Point

The obvious never-mentioned secret about Curteis Point was its assortment of oddball residents hiding out in the woods. Since houses were few back then and built deep in the forests, I did not know that famous authors lived along my road or that notorious war heroes inhabited the Point. Captain McLaren was one such. He had been a submarine commander in the War. We knew he must be alive, if unseen, for the haunting strains of the bagpipes he played each sunset. The music floated out to our shack in the darkness, calling the sea birds back home to the land. I could hear the seals snorting in the bay as we listened to the unseen piper. Rumour had it Captain McLaren had sunk many German u-boats and never got over it. The bagpipes sang of home to me like a lovely and sad lament.

At the end of the point lived M. Wylie Blanchet, aka “Capi” Blanchet, reclusive author of The Curve of Time. Capi, who looked to us like a scowling old witch of the woods, was scarily independent. She lived alone. After her children grew up, she became a wizened hermit with short grey hair and a nut brown face. She was wiry and agile. She couldn’t have been very old, but to children she looked old. We did not know that Capi must have been quite the feminist for the times, a woman who singlehanded took her five children on sailing trips along the rugged BC coast. Her husband had disappeared on one voyage. They never found his body. We heard stories that Capi chose to live with very little heat, rejected all help, was antisocial, and was rumoured to wash her dishes by leaving them on the beach for the tides to clean. She would take off in her Land Rover on road trips to Tofino or to kayak the Broken Islands alone or with her son. She never seemed to fear being alone with the storms. I wish I had ignored the gossip and overcome my fear of her. I needed help, particularly from strong women mentors like Capi. I had no idea help was merely a few trees away, just down the road.

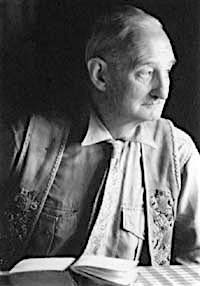

Half way to the ferry end of the Point at Swartz Bay lived the proper Pattersons. My sister and I used to swim on their public beach and merrily steal their apples. Their waterfront home looked like an estate resplendent with apple orchards and horses. I vaguely knew that R.M. Patterson was an author, but I knew nothing else. Much later, I discovered that he was an Oxford-educated Englishman who wrote many true stories about his adventures in Canada, including the well-known The Dangerous River (London: 1954). For years, he and his wife Marigold ran a cattle ranch in northern BC which, had I known it, would have made them human and approachable to me. We never saw much of the Pattersons because the children of the class of privileged people like Capi Blanchet, Captain McLaren, and R.M. Patterson were sent to private schools in Victoria and Brentwood. We were surrounded with a culture of writers who avoided us and perhaps also each other. Or so it seemed.

There were a few other respectable ex-military families in the woods, like Major Buckle or Captain Prentice, people with English backgrounds and accents and proper ways for children to behave and be educated, but the Campbells next door did not seem to be part of the class system.

We could actually see the Campbell home through our woods. Gray Campbell brought his wife and sons from Alberta, where he had served in the RCAF and then the RCMP. His handsome athletic sons were enviably upright and healthy, far beyond the reach of my sister and I, the prowling savages next door. My sister and I felt awkward around their wholesome boy energy. We hardly ever saw them, but they seemed to represent a shining integrity that shamed our world.

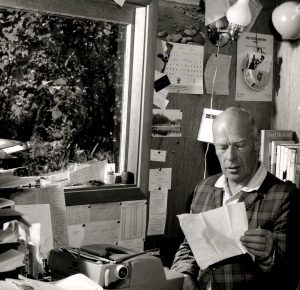

The Campbell boys might have been home-schooled. They lacked the stiff politeness of private school kids. We didn’t know that Gray Campbell set up a home-based publishing firm next door to us named Gray’s Publishing House. Gray must have collaborated with R.M Patterson and M.Wylie Blanchet, because he published their books. The Point was a veritable literary centre for recluses, geniuses, and alcoholics.

My wacky family of females lived smack in the middle of what I now thought of as the forbidden point of the early sixties. There was Irish; there was our elegantly alcoholic mother whose con-man husband had stolen the town’s money; then our dogs, our multiple wild cats, and “the girls,” as our mother called us. As budding teens who wanted to fit in, my sister and I longed for some semblance of normality. I assumed that the Point rejected us. Could it have been possible that people in those times of class systems and recovering veterans chose an isolation that had nothing to do with us? We didn’t know that everyone hid their demons in the woods and that normal was an illusion.

During the Irish saga, my sister and I laid claim to normal in differing ways. We began leaving home, or gradually running away from it. My sister wanted to be accepted and popular, and so she stayed with her girlfriends, who were the brainy and popular girls at school. Their families happily adopted her. They loved her sunny energy and her healthy moral effect on their children, who blossomed around her. When home, my sister was more loyal to our mother than I was. She hung around at night, keeping our drunk mother company throughout many a weeping story, hoping to offer some relief or comfort by listening to mother’s jumbled pain and incoherent memories. When I was home, I was kinder to Irish, but an iceberg to our mother. My sister, who blamed Irish for keeping our mother in booze, heckled Irish. Finally, Irish slapped her in the face during a heated argument about our mother’s drinking. My sister, the fiery and feisty redhead, vowed she would leave. She told me about one final incident that took all her young wits to manage.

That night, Irish and our mother got into a furious rage. Irish pulled a gun, rushed out to the deck, and shot it into the darkness. “Irish is killing me,” our mother screamed with her usual flair for drama. “Call the police! Get the gun!” shrieked our mother, too helpless to do it herself, and as usual electing my sister to do her dirty work. By then, Irish had scurried down to the beach. My sister groped her way down the steep path. There was no Irish to be seen. “Where was she? Had she jumped into the bay? Where was the gun? Would Irish shoot her?” She noticed a shape crouched in the dark, under the rowboat. It was Irish holding her gun. “Give me the gun, Irish,” she said quietly and kindly. Irish meekly obliged. My sister calmly took the gun, held Irish by the arm, and walked her back to our home. Mother had conked out. Irish blacked out on the couch, leaving my sister to fend for herself. Nobody thanked her for rescuing them.

Inwardly, my sister was shaking but throughout her life she looked outwardly strong. When she told me the story, I figured she was okay. I could not understand why she would bother with the drunks, or see the strain she must have felt to keep any sanity in the household. Fed up with the dramas, I ran off to re-invent home with an old Scotsman next door, named Mr Beatson.

Tryon Road and Mr. Beatson

On the other side of the trees, and just up from Captain McLaren’s woods, lived a staid retired couple in their seventies: Frank and Eva Beatson. Eva, who was Ireland-born, had married Frank in the Old Country. Frank, an engineer from Scotland, had patented some brilliant improvement to the internal combustion engine, which made him famous. He was slender, courteous, and always nattily dressed in his favourite blue wool cardigan with neatly pressed shirts and khaki pants. Mr. Beatson’s cardigan matched his honest blue eyes. He wore a dapper straw Panama hat over his freckled bald spot, which was fringed with hair that reminded me of a fatherly monk.

The silver-haired Beatsons were modestly well off and childless. They took my sister and me under their kind old wings during our mother’s final wars with Poppy. They invited us on outings to watch boring cricket games at Beacon Hill Park. They shared their black and white TV with us many a night when our own home felt like hell on the Point. They must have suspected the drinking. They might have been horrified when Irish arrived, but they never showed it. Mr. Beatson and I liked to play badminton, so I often showed up for games after school, while Eva served cookies on china with white linen napkins that she embroidered.

Sadly, in 1960, Eva died from heart failure. By this time, Irish had arrived. My sister and I began puberty and high school. It was a confusing time. I felt sorry for the grieving Mr Beatson, sitting alone in his dark house. I worried about him feeling as lonely and as lost as I felt when my father died. I determined to help. I formulated a plan. I would adopt the old Scotsman, and we could play badminton until I grew up and left for university. My sister could hold together the impossible home with our mother and Irish, which she bravely tried to do, at far more cost to her than I knew. It was a big job for a teenager, even a strong one like my sister. As far as I was concerned, managing two drinkers was a lost cause.

Throughout my teens, Mr Beatson became my closest friend/ grandfather. He fed me, clothed me, provided a safe haven for me. My popular and pretty sister moved in with her teen friends, whose families were charmed by her wit, intelligence, lovely long red hair, and huge brown eyes. Above all, she had integrity, which people respected. First I, and then she, abandoned Irish and our mother, who settled into domestic routines of drinking, fighting, and work. My sister and I loved and hated each other. There were days when we did not see each other; our lives cut off from each other. She called me an old lady. She had cute boyfriends, and I had fuddy old Mr. Beatson.

At school, I waged war on looking or acting like a girl until giving up at sixteen, when I noticed boys. I quit trying to be one. But how to act like a girl? It was far easier to apply myself to academics. Mr. Beatson helped me with homework. He gave me a dictionary and, whenever I had a question, would point me to it like the bible. He praised my high marks. Together, we ordered boxes of books for me from the Parliament Buildings Library in Victoria, which they mailed to the old red brick Post Office on Beacon Avenue.

Each day, as soon as I got back from school, I headed for Mr Beatson’s workshop where his white-fringed head was usually bent over the lathe. He was building a wharf with a pulley to lower his boat onto the ocean from the cliffs. The only swear words I ever heard from him were “dag nab it” and “drat.” He would show me his carpentry, and then I would run happily into his house for milk and digestive biscuits. I worked on my homework in his living room until dinnertime, which we made together. He cooked, I helped. His regular pressure-cooked meals of meat, cod, and Finnan haddie soon filled out my thin frame.

After hearty dinners with Mr Beatson, I tackled the homework again, or painted for fun, or read library books. I grew my hair long and quit curling it at night with beer cans, which, with my ears, must have looked ridiculous. For treats, we watched TV shows in black and white, like Gunsmoke or the Ed Sullivan show. At 9 p.m., I would sneak back to my spidery bedroom at my mother’s house. If she was home, my sister would wait up for me. Although I didn’t need it, she liked to fry me bacon and egg sandwiches before bedtime. I had no idea that she actually missed me and was lonely, or that her bedtime cooking for me meant a family mealtime for her. I simply never went home until bedtime.

“The girls” now had periods. Menstruation determined my third paid job in the world, and honest work at that: berry-picking. My sister and I worked hard labour on the Saanich farms, picking fruit, loganberries, and strawberries to save money for kotex, bras, nylons, and shoes. We rode our bikes for miles, as far as Central Saanich and Deep Cove. Socially, I was skinny, shy, and awkward. I depended on my pretty and confident sister to show me how to dance and dress or curl my wild hair. To attract boys, I had to sacrifice something, so I aimed for looking cute like her. Some kids said I looked Chinese, which hurt. This was not a compliment in the 60s. I wanted to look normal. I tagged along with my sister’s friends, even joined their teen dance club named The Sidney Stompers, but I never particularly fitted in or attracted the boys at school. Other girls in my class were engaged to be married by sixteen.

Mr. Beatson tried to help me look more respectable. He bought me boxy Oxford shoes, although girls in the sixties wore stacked heels. His earnest blue eyes shone with kind intentions, but he had no idea about fashion. Girls wore pointy bras and tube skirts, or puffy skirts with crinolines and nylons to school. He bought me a pastel green dress called a “shift” that I felt too ugly to wear. I had pale transparent skin with pimples, and those big ears which made pony tails out of the question. I thought that I resembled a sea cucumber with slits for eyes. Mother said I looked Mongolian. I believed I was ugly, until one day the boy in the desk behind me said: “I think you are exotic, like Sophia Loren.” Me like Sophia Loren, the gorgeous Italian actress with the dark slanting eyes and soaring cheekbones! The glamorous woman who created a trend in eye makeup with the liner that up-tilted the eyes! I never forgot that.

My two best friends throughout high school were Mr. Beatson and a 6-foot tall, smart, fatherless girl in my class named Jill. She was the boniest girl I had ever seen. Jill had large dusky blue eyes and long blonde hair that she skinned tightly back from her face. Like me, she was painfully shy. We both liked to read books together, when most girls in our grade were flirting with boys. Mr. Beatson and Jill were lifelines as I withdrew into an increasingly fearful life of borderline autistic silence at school. In spring and summer, I was miserable with hay fever, which inflicted sleepless raw-eyed nights of sneezing and struggles to breathe. Often, I found myself crying as though for my father. Or was it my mother? I felt like a nerd compared to my shining sister, who had become a leader at school. I was gaining weight at an alarming rate.

Consequently, I now hated my supernova thinner sister, and my super-loser mother. Mr. Beatson was my haven. He and I knew that I would eventually leave for university, but with him as a home, I could slow time while I figured out how to be a woman. By the time I was sixteen, any connection to my childhood home had ended. My sister and I only returned to sleep.

The Pointless Home

Irish loyally remained with our mother for fifteen years, long after we had left home in 1964, and long after the drunken rages became more violent. One stormy night, our tiny drunk mother threw Irish down the basement stairs, or was it over the deck? Despite her injuries, Irish remained with a stoical dignity. She took my mother to AA, where strident men required alcoholics to publicly list their wrongdoings as part of the making-amends program. This embarrassed and overwhelmed our fragile mother, who fled. Before the 1980s, there were no programs sensitive to women alcoholics. Yet it was the women who suffered the deepest guilt. They knew they had abandoned their families, and they could not face it. Drinking took all the pain away. My sister and I didn’t understand that. Neither of us ever touched a drop of liquor.

I must have been in my thirties when Irish, now an aging clerk at the same hardware store, realised the painful truth. She knew that booze was destroying her sanity and her self-respect. Her options horrified her: if she stayed on the Point, she felt she would either kill herself or that she would kill our mother. She picked up and left.

Irish hauled a trailer with her belongings onto the Indian Reserve. She sobered up cold turkey, became a vegetarian, and was adopted with respect into the Saanich native band. They saw into her great heart. She was the first white person to be allowed to live on the Reserve. Until the end of our mother’s sad life of isolation, Irish continued to watch out for her. She would phone and check on her, bringing more compassion than the white people in town had showed her. Our mother dwindled away to a skeleton.

In 1990, our mother died after years of drinking alone in the woods. She was aged seventy, the same age as myself when I first wrote this memoir of Curteis Point in January 2017. She had lain dead for a week, maggots had set in, and nobody knew or cared. Finally, Irish went to check on her after our mother’s phone rang unanswered for days. She found Cody, our mother’s starving old basset hound, fragile but still alive, having drunk dry the toilet in desperation. Since Irish was first on the scene, she was suspect; but the police soon cleared her when the coroner assessed that mother’s organs had shut down from chronic alcoholism. “All systems failure,” they called it.

My sister and I continued to watch out for Irish, long after we graduated as counsellors from university, long after my sister became a therapist and I launched my career with the government as an addictions specialist. Irish had kept us going with a patchwork home.

*

Postscript.

In 2015, I first visited my father’s grave in Le Vigan, France. I went with my cousin Carol Batchelor, a lawyer with the United Nations in Geneva. We each wrote goodbye letters to Alex, which we laminated and left at his headstone. We built a small stone cairn on the grave and lit a candle, because we wanted to hold our own memorial service. We read our letters aloud to him. We placed lilies on all seven graves. We had not been invited to the military funeral when we were children, and we did not know each other. This was the first time I ever met Carol. I have not been back since.

For Alex Batchelor’s air force career see W.R. Chorley, To See The Dawn Breaking: 76 Squadron Operations (Ottery St. Mary, Devon: W.R. Chorley, 1981), and J Douglas Harvey, The Tumbling Mirth: Remembering the Air Force (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1983)

*

Lee Reid is the author of Growing Home: The Legacy of Kootenay Elders (Nelson, 2016): reviewed by Duff Sutherland in the Ormsby Review (#369, September 8, 2018), and Growing Together: Conversations with Seniors and Youth (Nelson, 2018). See http://www.growinghomestories.com/ Reid says, “Writing a book about the challenges of aging and the creative lifestyles of rural seniors was easier than I thought. I had always wondered who lived up those mysterious long dirt driveways off the highways and in the forests of the West Kootenay, just as I once wondered about the mysterious homes and lives on Curteis Point. By 2016, I was old enough, or bold enough, to find out. My quest felt like a return to my childhood woods on Tryon road; it felt like a rite of passage where I could elicit guidance into my own aging while exploring the lives of seniors. This time, unlike my isolated childhood populated with war veterans, I would reach out to the people hidden in the woods. Perhaps those literary lights from my childhood inspired me more than I realised. For courage, I carried a slogan that the veterans, and my mother in particular, would appreciate: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle.” Lee Reid lives in Nelson.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

5 comments on “#431 The Spider Hunters”

Comments are closed.