#425 Let them have art galleries

Spaces and Places for Art: Making Art Institutions in Western Canada 1912-1990

by Anne Whitelaw

Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017

$39.95 / 9780773550322

Reviewed by Martin Segger

First published Nov. 16, 2018.

*

Geography challenges power. Anne Whitelaw has written an impressive geopolitical history of art institutions in western Canada. She demonstrates how the political craft of nation-building played out against a tableau of what she terms “centre-periphery relations.” The “centre” focuses on Ottawa and the “eastern” art establishment, of which the National Gallery in Ottawa is the key player.

Geography challenges power. Anne Whitelaw has written an impressive geopolitical history of art institutions in western Canada. She demonstrates how the political craft of nation-building played out against a tableau of what she terms “centre-periphery relations.” The “centre” focuses on Ottawa and the “eastern” art establishment, of which the National Gallery in Ottawa is the key player.

The “periphery,” of course, is everything to the west, and Whitelaw traces the emergence of professionalism in the visual arts clustered around major nodes such as Winnipeg, Regina, Edmonton, Calgary, and Vancouver.

Whitelaw is intimately familiar with the territory, as she taught for eleven years at the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta before joining the Department of Art History at Concordia University. She builds on earlier scholarly work such as Maria Tippett’s trailblazing Making Culture: English-Canadian Institutions and the Arts before the Massey Commission (University of Toronto Press, 1990), which is echoed in Whitelaw’s title.

Whitelaw structures her narrative both chronologically and thematically. Opening with how community arts organizations coalesced and seeded exhibiting institutions, she then examines how organizational structures emerged under the tutelage of the National Gallery. She identifies a common pattern. Local groups, usually women, organize for the arts. Exhibiting facilities are casual and temporary, from department store basements to rooms in libraries. Historic houses, acquired by donation, are the first exhibition facilities, and finally purpose-built, often monumental, art galleries are built. As professionalization of the industry proceeds it becomes more male-dominated.

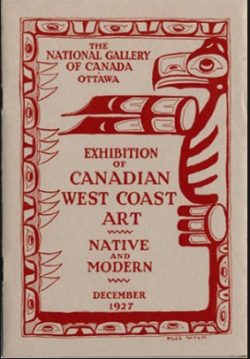

By the 1930s, the dominion government began formal planning for the arts sector, and direction by policy was eventually formalized with missions and goals articulated for the National Gallery. As local major institutions professionalized, standards were set for art handling and exhibition installation. Formal collections policies were developed. Artists formed self-help coalitions such as the British Columbia Society of Fine Art (1927), the Alberta Society of Artists (1931), the Canadian Handicrafts League (1932), the Federation of Canadian Artists (1941), and the magazine Canadian Art, founded in 1943. The Canadian Museums Association started (as an offshoot of the American Museums Association!) in 1947.

Seminal post-Second World War events such as the Massey Commission (1951) created funding mechanisms for the Canadian cultural diaspora, and then the National Arts Policy and the National Museums Act defined roles for the institutional infrastructure at federal, provincial, and municipal levels. Ironically, in the early years, major players were the American Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations, with funding actually dispersed through the National Gallery. The Canada Council for the Arts assumed that role after its creation in 1957.

As might be expected, the pushback from the regions appeared early on, manifesting as resentment that the National Gallery hoarded its collections, that loan terms were onerous, that artistic significance was centrally curated, that money was doled out parsimoniously, and that the regions were ill-represented in the national collections. In 1944, western community art exhibitors formed the Western Canada Art Circuit (WCAC) both to facilitate exhibition sharing among institutions but also to lobby the central Canada decision makers. Lawren Harris, resident of Vancouver after 1940, led a small group articulating “An Artists Brief,” which called for the federal government to coordinate national cultural activities and to subsidize a network of local artists’ coalitions and regional community arts centres, and even divest parts of the national art collections to them. The National Gallery resisted these fissiparous tendencies.

Services to the periphery soared in the decade following the disastrous fire in the Centre Bock of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa in 1916. The National Gallery was booted from the Victoria Memorial Building to allow for the temporary accommodation of parliament. The Gallery’s very existence, particularly funding, was then defined by a ramped-up travelling exhibition and speaker program. Despite this largesse, and on through the 1930s and 40s, the WCAC and western arts groups consistently resisted Ottawa’s paternalism as the West entered into a major spate of institution building. Vancouver was the first, opening an impressive purpose-built new facility in 1931.

Following the creation of a new arms-length National Gallery under the 1952 Museums Act, in 1958 the WCAC, led by Albertan Archie Key, prepared an elaborate agenda of demands directed towards the newly-founded National Gallery Exhibition and Extension Services Department. The demands were to be presented at a meeting of western art museums in Regina. At the outset, Richard Simmons, the National Gallery’s Extension Department director, took control of the meeting, sidelined the WCAC agenda, and mandated the terms under which the National Gallery would operate its loan policies, the guidelines under which it would circulate its exhibitions, and even suggested options for the future of WCAC, including dissolution.

Tables turned again with Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s appointment of the cerebral francophone journalist, his personal friend Gérard Pelletier, as Secretary of State (1968-73). Enamoured of Charles de Gaulle’s long-time Minister of Culture, André Malraux, Pelletier drove a total rethink of the role of culture in the national interest, particularly inspired by Malraux’s “democratization and decentralization” policies. The National Museum’s policy of 1972 created the pan-Canadian network of Associate Museums (mainly provincial entities) and National Exhibition Centres (for smaller communities), and then in 1997 the Museum Assistance Programs, all of which funnelled federal funds into ambitious collections development along with exhibition and facilities building programs, community outreach, and professional training initiatives such as university-based museums studies programs in the regions.

These initiatives fuelled a binge on monumental museum building across the country, although some were already underway. Whitelaw covers this in detail. Vancouver built first in 1951, followed by the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (1951, with adjacent exhibition galleries added, starting in 1955), Regina’s Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery in 1953/7, Saskatoon’s Mendel Art Gallery in 1964, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary in 1966, the Edmonton Art Gallery in 1969, and the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1971 — an architectural block-buster (literally). Ten National Exhibition Centres were created.

After 1957, the Canada Council for the Arts massively increased funding directly to artists and galleries to underpin gallery programming and outreach, and in 1960, the National Gallery finally moved into new quarters in Ottawa, but to the disappointment of many into a rather dreary repurposed office building, hardly fit for a national gallery in the nation’s capital.

It couldn’t last. By the end of the 1970s an economic recession had started to bite at all levels. However, by this time tensions at all levels were evident. The rising provincial and municipal institutions, which now saw themselves as equals to or even challenging the hegemony of the comparatively impoverished national museums, now forged international relations of their own, for example through the UNESCO-supported International Council of Museums. Even regional networks started to fray. The Vancouver Art Gallery, one of the first to do so, had dropped its membership in the WCAC in 1950.

Gérard Pelletier returned to the stage in 1984 as chairman of the Board of Trustees of the National Museums Corporation, and despite the rhetoric of regional outreach, ushered in the age of major monument building, glittering international starchitecture, at the nation’s capital. This has continued more or less unabated since the completion of Moshe Safdie’s new National Gallery of Canada in 1988. The newly-named National Museum of Civilization (and more recently renamed as the National History Museum) in Hull, designed by Roger Cardinal, the National War Museum, the Canadian Conservation Institute facilities in Gatineau, the Canadian Museum of Nature in the totally rebuilt Victoria Memorial Building — and yes, the Winnipeg-based Canadian Museum of Human Rights (2014), built on the Stephen Harper government’s private/public partnership model — are examples of iconic and highly visible starchitecture.

Canadians have, with characteristic restraint, tolerated these extravagances, concluding I suppose that big boys need big toys. Until very recently The Hill and its hallo of foreign delegations has been a male preserve. And after all, Canadians don’t go to Ottawa. The political mandarinate needs some stage furniture to compete with the New York/ Houston plutocracy and jet-setting international diplomatic delegations. Canada’s truly international-class art museums remain the heavily research-oriented Royal Ontario Museum and Le Musée des beaux arts de Montréal (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts) with its extensive European connections and innovative programs. Not far behind is the Ontario Art Gallery, built out under a series of American directors; the southward-looking Glenbow at Calgary, powered by international cross-border oil; and the Vancouver Art Gallery, west coast-oriented and headed up by a Californian.

In her epilogue, Whitelaw can’t help but note that despite this maturing of the art museum sector, old habits die hard. In 2009 the National Gallery announced an arrangement with the Art Gallery of Alberta to fund a new gallery at the AGA for the exhibition of works loaned from the NGC, to be called the National Gallery of Canada at the Art Gallery of Alberta, and then a similar arrangement with Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto. But there’s been no mention of a gallery in the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa devoted to the exhibition of regional arts.

Spaces and Places for Art is a genuine contribution to Canadian Art History, providing as it does a quite detailed account of the institutional and political backdrop to artistic production and aesthetic movements, and how creative expression intersected with national ideologies in the creation of modern Canada.

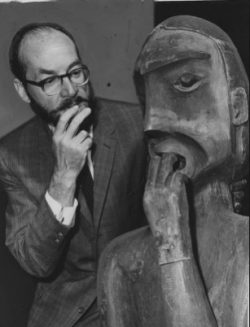

Perhaps it is unfair to ask for more from Whitelaw by way topic coverage. (Full disclosure: my own academic and arts professional career spanned over a third of the timeframe covered.) Fascinating actors walk only too briefly across the stage of her narrative. Many are names with which we are familiar: B.C. Binning, Lawren Harris, A.Y. Jackson, Eric Harvey, Archie Key, National Gallery directors Eric Brown, Harry Orr McCurry, Alan Jarvis.

Some are less known: Jerrold Morris, formative director of the Vancouver Museum, Alexander Musgrove of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Terry Fenton, who was critical in the development of the Edmonton Art Gallery, and Norah McCullough, a pioneer in arts education at the Saskatchewan Arts Board who then created modern outreach programming for the National Gallery. Unfortunately, we don’t meet them as rounded characters, and rarely do we get even a hint at what they looked like or how their personalities contributed to the story.

Some major figures are passed over or mentioned in passing. Later years saw the development of high-powered professional arts consulting firms such Lord & Lord, now an international company created by Gail and Barry Lord. Also absent is the Cambridge-educated Robin Inglis who, as director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum and of the Canadian Museums Association, nurtured the early professionalization of the industry. Tony Emery (1919-2016) appears briefly: the urbane, witty, intellectual gadfly who had already founded Pembroke College’s JCR Art Collection at Oxford University before emigrating to Canada as a high school teacher. He then started both the Art History Department and the Maltwood Art Gallery and Museum (1964) at the University of Victoria before being appointed director of the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1967, an institution he reinvented. After the VAG, Emery founded the art history department at Notre Dame University in Nelson before assuming the position of Dean of Fine Arts at Concordia University — Whitelaw’s academic home. Further research like this will expand the field she has marked out here. There is still much to do.

Spaces and Places is meticulously annotated with footnotes, a very complete bibliography, and summary index.

*

Martin Segger is a museologist and art historian whose career has included academic and administrative posts at the Royal British Columbia Museum and the University of Victoria. He has taught museum studies and art history at the University of Victoria since 1973. Author of numerous publications on the architectural history of British Columbia, including (with Douglas Franklin) the path-breaking Victoria: A Primer for Regional History in Architecture 1843-1929 (Heritage Architectural Guides, 1979), he also enjoyed a long career as a gallery curator focusing on B.C. historic and decorative arts. He currently serves as honorary art curator for the Union Club of British Columbia, and for Government House, Victoria.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.