#401 Legacy of Vitus Bering

First published October 16, 2018

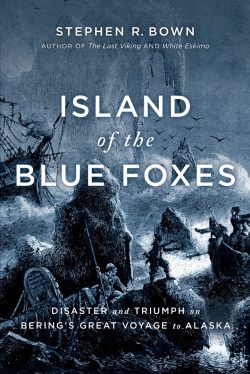

Island of the Blue Foxes: Disaster and Triumph on Bering’s Great Voyage to Alaska

by Stephen R. Bown

Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2017

$34.95 / 9781771621618

Reviewed by Robin Inglis

*

The Great Northern Expedition of 1733-1743, initiated by Emperor Peter the Great, extended Russian influence to the Aleutian Islands and to Alaska, which would remain a Russian colony until 1867. Led by the Danish explorer Vitus Bering, the expedition was a multi-national affair with German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller (Stöller) among its members.

The expedition’s legacy remains in the North Pacific, not just in the Bering Sea but in the plants, birds, and mammals identified by Steller, including the extinct Steller’s sea cow, the endangered Steller’s sea eagle, the inquisitive Steller’s jay, and the raucous Steller’s sea lion of coastal British Columbia.

In Island of the Blue Foxes: Disaster and Triumph on Bering’s Great Voyage to Alaska, Stephen Bown tells the story of this great voyage of exploration. Reviewer Robin Inglis commends Bown’s account of the expedition’s near-fatal ending after being shipwrecked in 1741 on a desolate island in the Aleutian Chain inhabited by feral blue foxes, a chapter that Inglis calls “a splendid, informative, and empathetic piece of writing.” — Ed.

Historians of the early exploration, contact and fur trade period on the Northwest Coast of America have usually identified the 1741 Russian voyages of Vitus Bering in the St. Peter and Aleksei Chirikov in the St. Paul as the “starting point of the story:” nevertheless, they have also tended to regard the Russian presence and contribution “in the far north” as secondary to such other, seemingly more important, themes and issues as the Spanish voyages and occupation of Nootka Sound, the visit of James Cook, the Nootka Crisis, and the feverish activity of the fur trade dominated first by the British but increasing by Americans out of Boston.

Historians of the early exploration, contact and fur trade period on the Northwest Coast of America have usually identified the 1741 Russian voyages of Vitus Bering in the St. Peter and Aleksei Chirikov in the St. Paul as the “starting point of the story:” nevertheless, they have also tended to regard the Russian presence and contribution “in the far north” as secondary to such other, seemingly more important, themes and issues as the Spanish voyages and occupation of Nootka Sound, the visit of James Cook, the Nootka Crisis, and the feverish activity of the fur trade dominated first by the British but increasing by Americans out of Boston.

If never actually a mere footnote, the remarkable achievements of the two Russian navigators have never been given due recognition. This despite the fact that the Russian trading advances towards America in their wake, which began before 1750 and gathered pace thereafter through the Aleutian Islands and onto the Alaska Peninsula and south down the coast, led to the establishment of “Russian America” by the end of the century.

The Russian advance ultimately caused a determined Spanish response that, post-Cook, led to the Nootka Incident and Crisis and the fur trade activity that engulfed the region, extensive Euro-American contact with the native peoples of the coast, and exploration initiatives by the imperial navies of Spain, Britain and France (1774-1794) that provided a precise charting of the entire coast from California to Alaska.

Thus, the appearance of this well written narrative history of the beginnings of Russia’s active involvement with the North Pacific is a welcome addition to the historiography. It successfully synthesizes both long-standing and more recent scholarship — written in English or in English translation — that deal with Bering and Chirikov and the two Kamchatka Expeditions of 1728 and 1741-42. At 273 pages with endnotes rather than footnotes, this is an eminently approachable book and any general reader with an interest in exploration, and North Pacific America especially, will find it an excellent introduction to the two voyages — primarily the second one, the book’s major focus — on which the St. Peter and St. Paul, sailing separately shortly after leaving Asian waters, actually reached America.

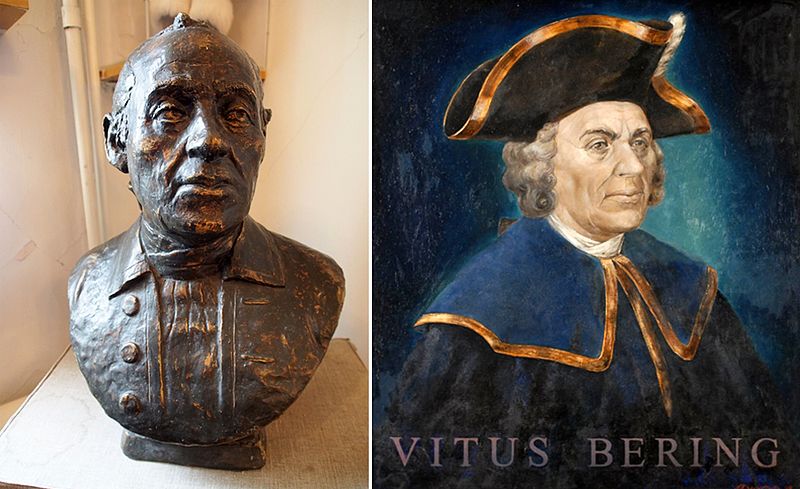

Bust of Vitus Bering (1681-1741) and 1991 portrait — both based on post-mortem reconstruction. Russian Academy of Sciences

For those readers who want to delve deeper, Bown provides a short article on further reading, and a limited bibliography. For much more depth I would complement these with the listing in Orcutt Frost’s 2003 biography, Bering: The Russian Discovery of America and suggest reference to Raymond Fisher’s illuminating essay “Finding America” in Sweetland Smith, Barbara and Raymond Barnett, eds. Russian America: The Forgotten Frontier (1990).

The title of the book is explained in a short prologue in which the St. Peter carrying Bering and his scurvy-ridden companions are struggling home, trying to reach Kamchatka, but instead find themselves driven onto a desolate island a mere week from their destination: here they are initially terrorized by numerous blue foxes. Thereafter, in four separate parts, the author fills in the backstory.

In Part One, “Europe” (although it includes Bering’s first foray across the continent and first Kamchatka voyages), we learn about Tsar Peter the Great’s determination, following a revealing fifteen-month tour of Western Europe, to modernize Russian government and society, her army and navy; he had been amazed by the economic and cultural wealth he witnessed. His interest had been piqued in Holland by early maps and conversations that presented theories about the still-vague relationship of Asia to America. Once his two-decade war with Sweden, that gained Russia a substantial presence and a new capital — St. Petersburg — on the Baltic was concluded in 1721, the restless tsar was free to turn his thoughts to a more effective unlocking of the riches of Siberia; to a better understanding of the Pacific edge of his empire; and to the dream of accessing the reputed wealth of America.

Here, also, we meet Vitus Bering, one of a number of foreign mariners who had become officers in the expanded Russian Navy. In the Great Northern War he had been competent and trustworthy and on one occasion saved his ship in a failed Russian campaign in the south against the Turks in 1711 by bringing her safely home. But it was his talent for organization and administration that gained the respect of his superiors, so that when the Admiralty was preparing a list of potential commanders for a voyage aimed at finding America, Bering came to the fore, having also experienced voyages to Atlantic America, the West Indies, and Indonesia.

In the 1720s there were essentially three parts to the Russian Empire — Europe (and Peter naturally regarded Russia as very much a European nation), Siberia, and the eastern or Pacific seaboard. The vast swath of the continental interior was largely unsurveyed and roads east of Tobolsk were essentially non-existent; progress involved substantial portaging and use of rivers. The sea route from Okhotsk to Kamchatka had only been pioneered in 1716, and in 1719 the tsar launched an initial exploration of the peninsula with orders to probe east towards America and south towards Japan and the Philippines. In the absence of progress on these maritime fronts, these twin goals became central to the seaborne part of Bering’s First Kamchatka expedition.

First, however, Siberia had to be better understood and surveying was a key part of the whole endeavour. Bering was called upon to employ all his skills as a leader and administrator to organize and direct disparate parts of the group that made its way across Asia. His imperial charge to demand human and material support strained local resources and the mountains between Yakutsk and Okhotsk proved an immense challenge. Treacherous trails became staggeringly difficult to negotiate; horses died, food became short, and men deserted.

Finally Okhotsk was reached, by which time we have been introduced to two leading naval officers, Chirikov and Martin Spanberg, who would later feature in Bering’s second, “Great Northern Expedition.” In the summer of 1727 Spanberg completed the ferrying of the expedition from Okhotsk to Kamchatka and that winter the St. Gabriel was built and finally launched in July 1728. The effort to find America could then begin. It is clear that the Russians had no concept of the distance between Kamchatka and Alaska in the mid latitudes and that the idea of an island — Juan de Gama Land — between Asia and America was still in vogue.

Bering’s orders to sail “along the coast that goes to the north” is more likely along this island on the way to America (it appeared on a map known to the Tsar Peter) than the standard view that he was to sail up the coast as we now know it towards the strait that bears his name. The St. Gabriel, however, basically followed this latter route, proceeding through the strait and back without getting any glimpse of Cape Prince of Wales on the American side, shrouded in summer fog. Bering had reached 67°24′. In 1729 he made another short excursion directly to the east for some 130 miles, but at this point Alaska is over 700 miles away and he found nothing. He sailed back to Okhotsk and began the long trek back to St. Petersburg arriving in February 1730 — five years after departing in 1725.

Bown ends this section of the narrative with the plans for another voyage. Empress Anna is now on the throne and she was prepared to entertain Bering’s request for another expedition that would build bigger ships and continue explorations east and south of Kamchatka. His report on his first endeavour was persuasive in stating that the eastern seas and America could be revealed and that his new map of Siberia would hasten a second expedition’s progress across the continent.

To justify the expense of such an expedition, however, it was also determined that a route to Japan would be charted and new charts would reflect extensive surveys of the north coast of Siberia. But what dismayed Bering was that the relatively tight expedition plans grew exponentially to include transportation, trading, settlement, and taxation infrastructure. As Bown describes it, the secondary objectives became “not geographical but rather political and colonial.” In addition the Academy of Scientists envisioned a wide-ranging scientific component; the expedition was to study plants, animals, minerals, and report on native peoples and economic possibilities.

Steller’s sea cow (now extinct), seal, and sea lion from Sven Waxell’s 1744 chart of the Russian Expedition to America. Russian Naval Archive, St. Petersburg

The Great Northern Expedition became the most ambitious ever undertaken by any nation. Bering became commander of a contingent that would number in the thousands — “scientists, secretaries, students, interpreters, artists, surveyors, naval officers, mariners, soldiers and skilled labourers, all of whom had be brought to the eastern coast of Asia across thousands of miles of roadless forest, swamps and tundra, again hauling vast quantities of equipment and supplies because there would be nowhere to purchase these items in Siberia.” Instructions went out from St. Petersburg that local authorities were to offer all support to Bering, but, as with his first expedition, personal incompetence and resentments and lack of local skills and resources undermined him. It was a herculean task for any commander and it all meant that Bering was a very tired man when, eight years after setting out from European Russia, he finally was able to sail for America in 1741.

Part Two, “Asia,” covers these exhausting years. Bown writes not only about the journey but also the development of personal battles and conflicting and often damaging reports that were sent back to the capital by various factions. The scientific corps was at loggerheads with Bering almost from the start. In this section, however, we meet Georg Wilhelm Steller (1709-1746), the brilliant scientist whose contradictory personality and arrogance endeared him to few of his colleagues. Highly intelligent, he was also impetuous in his opinions, stubborn and often belligerent, but he emerges in Parts Three and Four, with officer Sven Waxell, as the hero of the piece, notably in the final desperate months on the island as the two men rally the survivors to actually survive and make it home to Kamchatka.

Steller came east quite late in 1738 but found himself studying in Kamchatka when Bering was finalizing preparations for the voyage, and he joined the search for America. His journal would provide the most illuminating account of the expedition in 1741-2, and until more recent scholarship developed a more rounded view of the entire endeavour, largely defined it with an image of uninspired and moronic officers and a largely unflattering portrait of Bering. Until 1991 Bering was also ill-served by a painting long thought to be of him as short, overweight and flabby-faced, but now considered to be of his great uncle. Research done in the 1990s from strong evidence of the location of his remains on Bering Island, suggest a man of commanding presence with a strong Nordic face who until his last few weeks was in reasonable health and who didn’t die of scurvy but of heart failure. Although weighed down by the ongoing preparations and cross-continental efforts required of the expedition, there is every reason to believe that he was re-energized by the voyage itself, while rightly concerned about the welfare of his ship and his men.

The most illuminating way to appreciate the challenge of the voyage to America from Kamchatka is to look at a globe and not a “flat” map on the printed page. Only then can one really grasp the distances involved and the unfortunate influence of noted French geographer Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, who as early as 1731 had produced a map showing the phantom Gamaland south and east of Kamchatka. This had misled Bering in 1725 and it was to do so again despite the explorations of Spanberg’s expeditions to Japan, 1738-39, and the opposition of both Chirikov and Waxell. Delisle’s brother, Louis Delisle de la Croyère, was to sail with Chirikov and he came to the council of officers that — in the tradition of the Russian navy — was called to determine the route to America – with maps and strong arguments.

Thus, when the St. Peter and St. Paul sailed away from Kamchatka on June 4, 1741 they headed south, south-east as low at 45°N which massively increased the distance to America when they finally turned east. By this time the ships had become separated in fog and stormy winds; they would never again see each other over the summer during entirely different voyages to and from America.

An Aleut in his baidarka. Drawing by Sven Waxell or Sofron Khitrov on 1744 chart of voyage. Ministry of Marine, Petrograd

In Part Three, “America,” the pace of Bown’s narrative increases. He intersperses the story of both Bering and Chirikov, but clearly the former takes centre stage primarily because of the presence of Steller — and to a lesser extent Waxell, who increasingly takes over the St. Peter from Bering — and their journals. Steller’s journal, despite his belligerent self-interest, is a remarkably perceptive piece of writing. By June 25th, Chirikov and his officers had decided to proceed alone and by mid-July they were off the Alaska panhandle. A longboat was launched off Yakobi Island to investigate the shore for an anchorage and to fill the water barrels, but five days later had not re-appeared suggesting to the commander that the boat had either been swamped and the men drowned, or that they had been fatally attacked by Tlingit natives. A second ship was sent out, but it too disappeared.

Bown seems to think that the men had drowned, making the curious statement that relations between Europeans and Tlingit were frequently harmonious. But the Tlingit were known for their ferocity in defending their territory and in later years the Russians, who claimed but never really controlled that territory, were regularly confronted or attacked, and ventured only up the coast’s inlets with exceeding caution. As Vancouver’s biographer, Bown would have known that the British were ambushed in 1793 and that the captain could easily have lost his life.

Although native canoes approached the St. Paul, no effective communication could shed light on the disaster of losing his two small boats, and Chirikov was forced to head home immediately. Increasingly short of food and water, and facing stormy weather, the voyage became increasingly difficult. There was an interesting encounter with Unangax (Aleuts) off Adak Island in early September, but otherwise the last stages of the voyage were a battle against the elements and particularly scurvy, which Bown describes in some detail. Men began to die. The St. Paul finally entered Avacha Bay to arrive at Petropavlosk and most of her surviving crew had to be carried ashore: of an original complement of 76, 21 men had died – fifteen in Alaska and six during the waning days of the voyage. The “triumph” of finding America had proven to be both costly and without any really obvious benefits — scientific or economic.

By mid-July, after nearly six weeks at sea, Bering and the St. Peter were also nearing Alaska, and within a week had landed on Kayak Island. Bering proved abundantly cautious, worried about unknown dangers and the lateness of the navigation season, and initially prevented Steller from going ashore. There were fierce arguments. Stellar recorded in his journal the immortal phrase, dripping with sarcasm, that they had come all this way merely “for the purpose of bringing American water to Asia.” Threatened that Steller would report him to the Academy of Sciences and the Admiralty, Bering relented. Consequently, Steller frantically made notes about the climate, soil and plants, identifying the salmonberry and Alaskan wild cherry, and recorded his impressions of the animals, including the red fox and birds such as the blue jay, later known as Steller’s jay.

No natives were encountered but Steller found evidence of human habitation, including smoldering fires, trails, and tasty smoked fish. He also found a storage pit and collected items for which Bering ordered payment in cloth, knives, tobacco, and beads. Steller continued his investigations – flora, fauna and sea mammals (including a “sea ape,” probably fully grown male fur seal or a young northern fur seal) — and recorded descriptions of natives encountered as the St. Peter touched on the islands protected the Alaska Peninsula. For Bering and his fellow officers, Waxell and Sofron Khitrov, there was increasing frustration, even panic, in being driven by storms far too far to the SW rather than being able to proceed directly along the 53rd parallel towards Kamchatka.

As August turned into September and October, they were still far from home and scurvy had made an appearance. Late that month the weather improved and the St. Peter was able to claw back to the north and west the lost miles due to the stormy weather. Finally, in early November with men dying almost daily, land was sighted; it was thought to be Kamchatka and a chance to follow the coast north to Avacha Bay, but this proved an illusion. Instead, anchored off an inlet and bay, the helpless St. Peter was caught in a sudden storm and driven over a submerged reef into a lagoon on the shore of the Island of Blue Foxes.

In Part Four, “Nowhere,” Bown recounts the horrors but final salvation from nine months on the island. It is a splendid, informative, and empathetic piece of writing. By this time, twelve men had died of scurvy, and 49 of the 66 survivors (74 percent) were officially on the sick list. As the sick were ferried ashore – some initially remained on the ship as they were too ill — an encampment was set up in the sand dunes behind the beach, and Steller discovered a stream with good fresh water and plants which he began to use for salads and soups. Birds were shot and seals and sea otters were easily hunted. This and the topography persuaded Steller, who basically assumed control of the situation as both Bering and Waxell were still very feeble, that they had not reached Kamchatka but were on an island. Later exploration proved this to be the case.

Burrowing into the dunes and constructing shelter from driftwood and the bodies of killed foxes, the men were divided into small, self-managing groups to aid morale, shelter, rest and eating and a relaxation of naval discipline. Fresh meat and water and Steller’s plant-based soups complemented the ship’s rations and began the recovery. But it was slow as some were very sick, cold, and too feeble to eat and drink. Some never made it off the ship. A total of nineteen men died of scurvy and other illnesses before Steller’s diet could work its magic: Bering was among them as the disaster added grief to his fatal ailments. He died on December 8th. To pass the time in the dark and cold, Waxell, who had assumed command of the voyage, allowed cards and gambling. As animals and driftwood near the camp became scarcer, battling storms to hunt and gather was necessary farther afield, but as January wore on the survivors had recovered their basic health, ultimately benefitting from two whales that washed up on shore.

Waxell now convened a council to inspect the ship. It was soon decided that it was beyond repair, and should be broken up to build another one. But destroying government property was not to be taken lightly and a series of formal reports had to be written to explain the decision. Waxell cleverly consulted widely and debated all options to keep a focus on the best ways to leave the island, finally creating a consensus. Construction of the escape ship began in early May and the remnants of the expedition to America, sailed to safety in mid-August. By that time Steller, as scientist, had investigated the island’s natural environment; explorer, collector, describer and speculator, he left an enduring legacy, researching the Arctic fox, the sea otter, the sea cow or manatee (also a vital source of fresh meat) as well as the flora. He returned to Kamchatka with a collection of over 200 plants.

In an epilogue, Bown wraps up a number of threads: the fate of the expedition’s leading participants (Waxell remained in the navy and lived until 1756; Steller continued his scientific work in the east until his premature death at 35 from an alcohol-induced fever while returning to St. Petersburg in 1746), and the fur rush across the Aleutian Islands that ultimately resulted in the establishment of Russian America. Despite the important fact that the expedition finally found America, that achievement was limited in the context of the Tsarina’s immediate dreams of economic and commercial wealth and the co-opting of the tribute-paying natives into the empire. But Bering’s personal achievements over a decade of leadership, never celebrated by his contemporaries or indeed since that time, deserves the respect that would place him in the pantheon of the world’s great explorers.

His story and that of his two expeditions is worthy of the telling, and Bown has produced a valuable book that is recommended as a great introduction to the subject. My only disappointments are that there could have been more “local” maps (Kayak Island and Bering Island, for example) in addition to the ones of the Russian Empire and the expedition routes, and higher quality illustrations. Some more modern images, such as of the mountains passes east of Okhotsk, the islands guarding the Alaska Peninsula, and Bering Island would have been useful.

*

Robin Inglis is a former Director of the Vancouver Maritime Museum and the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. After graduating from Cambridge University with a degree in history, he came to Canada and taught for a few years before taking a Master’s degree in Museum Studies at the University of Toronto. In North Vancouver, he took a special interest in the history of the community, especially its waterfront, and oversaw the opening of a new Community History Centre/ Archives in Lynn Valley in 2006. Since the 1980s he has studied, written, lectured, and curated major exhibitions on the early exploration of our local Pacific coast, completing in the Historical Dictionary of Discovery and Exploration of the Northwest Coast of America (Scarecrow Press, 2008). Robin has received decorations in recognition of his work as a museum professional and historian from the governments of France, Spain, and Canada, and he is a Fellow of the Canadian Museums Association. He lives in Surrey, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster