#368 “Walk like an Indian”

Kuei, My Friend: A Conversation on Race and Reconciliation

by Deni Ellis Béchard and Natasha Kanapé Fontaine, translated by Deni Ellis Béchard and Howard Scott

Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2018

$19.95 / 9781772011951

Reviewed by Dylan Burrows

First published September 07th, 2018

*

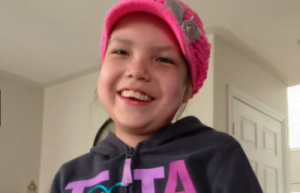

Following the controversial death of 11-year old Ojibwe girl Makayla Sault from leukaemia in 2015, after her parents refused chemotherapy on the girl’s behalf, Vancouver-born Canadian-Québécois-American writer Deni Ellis Béchard and Innu poet Natasha Kanapé Fontaine exchanged 26 letters that are the core of Kuei, My Friend: A Conversation on Race and Reconciliation.

Dylan Burrows reports that Béchard and Fontaine “craft an insightful dialogue on the intergenerational legacies of racism, discrimination, and genocide in contemporary Canada.”

“Québécois will understand what it means to ‘walk like an Indian,’” writes Natasha Fontaine. “Walk in their shoes. I believe that the day will come soon where ‘Indians’ invite the ‘Whites’ to make a journey with them.” — Ed.

*

In Kuei My Friend, Québécois writer Deni Ellis Béchard and Innu poet Natasha Kanapé Fontaine talk frankly about anti-Indigenous racism in Canada’s era of so-called reconciliation. By turns insightful and painful, Kuei elevates the simple act of letter writing into a treaty-making dialogue: a promise to jointly pursue an authentic rapprochement between Canadians and their Indigenous hosts.

In Kuei My Friend, Québécois writer Deni Ellis Béchard and Innu poet Natasha Kanapé Fontaine talk frankly about anti-Indigenous racism in Canada’s era of so-called reconciliation. By turns insightful and painful, Kuei elevates the simple act of letter writing into a treaty-making dialogue: a promise to jointly pursue an authentic rapprochement between Canadians and their Indigenous hosts.

This new edition brings Béchard and Fontaine’s prescient work to English-speaking audiences far beyond Québec’s borders.

Kuei arose from the co-author’s encounter with Québécois journalist Denise Bombardier at Sept-Îles’ North Shore Book Fair on April 27, 2015. In January of that year, Bombardier ridiculed Indigenous culture as “deadly” and “unscientific” in a blog following the death of Makayla Sault.

The 11-year old Ojibwe girl succumbed to leukemia after she sought traditional medical treatments and homeopathy instead of chemotherapy against her physician’s wishes.

Surrounded by Innu women, Fontaine tried to read to Bombardier a letter that expressed the hurt the journalist’s words caused during a panel session. She quickly confronted, however, the “abyss of human ignorance and arrogance” (p. 18). Bombardier cut Fontaine off, and read aloud her own definition of “Amerindian” — French for “Indian” — from her most recent novel.

A witness to Bombardier’s condescension, Béchard approached Fontaine afterwards. Their subsequent conversations kindled not only an enduring friendship, but also an introspective correspondence.

Across 26 letters, they craft an insightful dialogue on the intergenerational legacies of racism, discrimination, and genocide in contemporary Canada.

The book also includes three appendices: a chronology of events that led to the establishment of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls; an English to Innu-aimun lexicon; and questions and exercises for educators to use in the classroom.

Kuei’s success lies in its co-author’s insistence that the past is not the past. As the beneficiaries of the historical and ongoing exploitation of Innu lands, Québécois bear the onus to advance economic and political reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

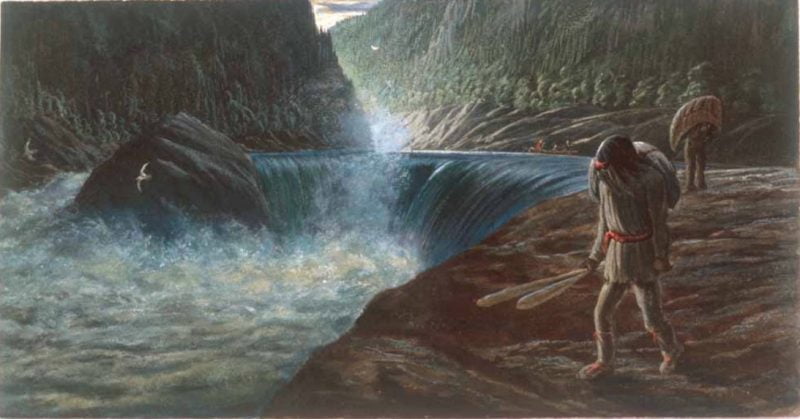

This book also forces Québécois to reckon with their “ancient heritage:” that, over centuries, Innu lands shaped their very character as a people. As Béchard reveals in an early letter, a family genealogy project reminded him of a memory of his grandmother, who once said his ancestors “walked like Indians” (p. 32).

Fontaine ponders at length at the importance of this family history. Rather than evidence of having “Indian blood,” she sees it as a reflection of how Béchard’s family adapted to the customs of Indigenous lands. “One day, perhaps,” she writes,

Québécois will understand what it means to “walk like an Indian.” Walk in their shoes. I believe that the day will come soon where “Indians” invite the “Whites” to make a journey with them. And the latter will perhaps notice that it is comfortable to walk in shoes that don’t imprison feet. Shoes that are adapted to the territory, shaped by it. And that brings them freedom (p. 38).

Béchard and Fontaine set out on their own such journey with each exchanged letter.

Personal accountability figures centrally in their method. They relentlessly question how, as individuals and members of their respective communities, their actions reproduce the very forms of discrimination they call out in their letters.

*

Béchard reckons with the layered nature of Québécois racism through childhood recollections of his father’s bigotry. Virulently anti-Indigenous, the elder Béchard also bore a deep self-loathing nurtured by English-Canadian stereotypes of Québécois inferiority. Only after years of anti-oppression work, Béchard writes, did he realize how our worst impulse to dehumanize marginalized peoples sustains the very powers that oppress us.

Fontaine, in turn, writes honestly about Innus’ struggle to heal from the “wound of Colonization.” The “vile, genocidal, alienating intention” behind Canada’s reservations and Indian residential school system, she writes, lingers like a poison in Indigenous minds and bodies (p. 47).

Fostering empathy, not guilt, drives Kuei’s dialogue. The co-authors speak in turn, listen, and emphasize with one another’s experiences with oppression. Hardly a panacea, they argue that empathy can propel us to takes steps towards tangible, even radical social, economic, and political change.

The frequent use of Innu-aimin — the Innu language — lends Kuei its transformative power. When Béchard and Fontaine address their letters with “Nuitsheukan,” or “my friend,” they acknowledge one another as more than correspondents. They are partners in rethinking the process of reconciliation.

Innu intellectual traditions also shape their dialogue about a future without colonialism. Pressed by Béchard, Fontaine approximates “freedom” as “Nitipenimitishun”, or “I am master of myself:” an autonomy tied to bodily and political sovereignty (p. 78). The included lexicon lets the reader keep track of Innu-aimin terms, idioms, and concepts throughout Kuei.

Some things do get lost in translation. As one of two translators, Béchard renders “allochtones” — French for “non-natives” or “settlers” — as “Whites”, a decision he justifies at length (p. 5). This unfortunately frames reconciliation as a responsibility exclusive to Indigenous peoples and settlers of European-descent.

How would the conversation change if recent immigrants, refugees, or people of colour added their voices? What permutations would it undergo if they talked with Indigenous peoples without triangulating the conversation with “Whites” altogether?

This is a glaring omission given that the book is intended for use in schools. Example exercises ask students to research, and then write about racism to peers from “different communities” (p. 154). Who these communities are, and how they are “different” remain vague.

Other questions within the letters themselves go unanswered. Towards the end of their correspondence, Fontaine poses to Béchard an incisive question. “What is your relationship with the idea of Indigeneity,” she asks, “now that I have revealed so many secrets to you?”

Béchard’s answer is anticlimactic: Indigeneity is tied to an “openness” to other intellectual and cultural traditions outside his own. Perhaps, he, like Kuei’s readers, is still learning to listen.

Nonetheless, their letters shake up the stultified debate spurred by the 2015 publication of Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada’s final report. Political leaders quickly recognized the TRC’s damning conclusions, but few have paid more than lip service to implementing its 94 calls to action.

Kuei ultimately pursues honest, open-ended dialogue over political expediency. Through their letters, Béchard and Fontaine chart future possibilities for reconciliation.

*

Dylan Burrows is an Indigenous Ph.D. candidate at UBC’s History Department. Raised in Nishnaabeg territory in what is now Central Ontario, he lives and works as a guest on the ancestral, traditional, and unceded lands of the Coast Salish peoples. His doctoral research currently focuses on the nature and meaning of Inuit labour under the aegis of Danish, British, and Canadian Arctic exploration and sovereignty exercises during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He lives in Vancouver.

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Editor/Designer/Writer: Richard Mackie

Publisher/Writer: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. As of September, 2018, Provincial Government Patron: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.