#281 Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Jamie

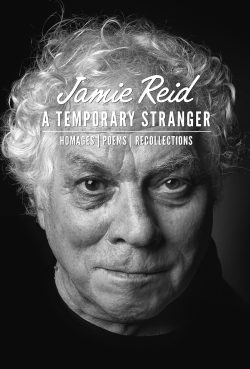

A Temporary Stranger: Homages, Poems, Recollections

by Jamie Reid

Vancouver: Anvil Books, 2017

$18.00 / 9781772140989

Reviewed by Andrew Parkin

First published April 4, 2018

*

In a posthumously published collection by Vancouver poet Jamie Reid (1941-2015), there are poems of homage to a number of famous French poets from Baudelaire to Apollinaire, including Reverdy, one of the late Michael Bullock’s favourites. There are also what Reid called “fake poems” (maybe anticipating the term “fake news,” a rather different animal) and short essays called “Recollections” on writers that include bill bissett, Dylan (Bob, not Thomas) and John Newlove. And finally there are reprints of reviews or short review articles.

In a posthumously published collection by Vancouver poet Jamie Reid (1941-2015), there are poems of homage to a number of famous French poets from Baudelaire to Apollinaire, including Reverdy, one of the late Michael Bullock’s favourites. There are also what Reid called “fake poems” (maybe anticipating the term “fake news,” a rather different animal) and short essays called “Recollections” on writers that include bill bissett, Dylan (Bob, not Thomas) and John Newlove. And finally there are reprints of reviews or short review articles.

Karl Siegler’s Foreword gives us a careful discussion of Reid’s preoccupations as a poet and the use of the term fake poems. The concept derives from the wily old master of all subsequent theory, to whit of art as imitation: ’Arry Stotel — I’m following Jamie Reid’s example when his Homage to Apollinaire is simply a pun: Apple in Air. The Victorians liked puns but we should note that the pun has been called the lowest form of wit. The pun on Apollinaire is by no means homage to him as a poet.

In my view, the section of homages to well-known and sometimes fashionable French poets is really a bit of intellectual name-dropping. Reid’s poems recall very little of these poets’ achievements.

The reference to the Montparnasse district of Paris shows superficial knowledge rather than any real homage to Romanian-French poet, Tristan Tzara. People in France do not play bowls on gravel in courtyards. Gravel is for games of boulles or pétanque where indeed “balls” are “tossed high into the air” sometimes and not usually “black” (like bowls in Stanley Park) but are made of grey metal. The French who play bowls with black wood, play like the English and other enthusiasts on the levelled lawns, onto which circular rubber mats descend as if they were earthly flying saucers. This isn’t pedantry. I think it best to realize how imperfect Reid’s knowledge is of the poets to whom he pays homage.

In Paul Eluard, we find a poet who confronts “La Vie immediate” (the title of one of his volumes) and tells us “Nous sommes tous sur le même rang” (“We’re all at the same level”). He is not a theoretical intellectualizer. He observes what is happening around him on an ordinary rainy day. In his poetry a woman in an apron watches the rain on the windowpanes. He observes life as it appears around us all. Reid’s homage to him is one of the better poems in this section. It is marred to my mind by introducing puns into the scene: “burrows/borrowing” and “fluttering flattering tongues” (p. 28).

More seriously, in the poem itself, Reid refers to Rimbaud’s lack of published work from his North African career. But Enid Starkie and others have longed for the discovery under some Sahara dune of a briefcase crammed with Rimbaud’s later poetry written when he was bumming, bartering, and maybe gun-running there. Reid could have written a really fake poem, a fake Rimbaud celebrating a drunken camel ride rather than a drunken boat. It seems that Reid’s knowledge of modern French poetry is sketchy and relies just on some translations.

The best of these poems for me is the homage to Baudelaire. It seems to get closer to Baudelaire’s acidic flavour and sensibility than I had expected. Reid’s detail of a white handkerchief in Baudelaire’s pocket is a gesture to the gentleman’s house on the Royal side of the Seine with its windows looking towards the Collège de France, the Latin Quarter, and the Sorbonne. But a faint scent of Baudelaire the merciless joker at the expense of the Belgians or the satirist of women is a trail not picked up by Reid.

Reid’s sequence of fake poems reveals that he is indubitably a real poet who doesn’t need to drop the names of French predecessors. If Aristotle said that art was an imitation of nature, we can add that art is art because it is not nature, and that it transforms and makes external nature an essential part of our human nature. Here I think the idea of “fake” is inappropriate. To copy and transform nature is not a fake unless deception is involved. A fake is something passed off as if it is the real thing. It’s a pejorative term.

But as Reid says in his introductory statement to his fake poems, “There is no art on earth that can fully represent the exact and flowing experience of viewing stone within the flow of water and the waving light within the water and around the stone….” (p. 37). We know what he means. But the camera can give us the experience of viewing nature; what no art can do is give us the sensations and feel of the scene, as he says a few lines later. We cannot, through art, be there in the flesh surrounded by the rush, the sounds, and the scent of it all and the individual way it affects our nervous system. So yes, let’s assume art, poetic art in particular, is not whatever it describes.

The poem though, if it is not a fake in a pejorative sense, is nature and human nature remade and transformed by means of the poet’s voice. When the poet speaks her or his poem aloud, or it is spoken by others who know it but didn’t write it, the experience of poetry is established as part of what’s going on in the real world. Human experience is part of the reality of things. That is one of the major themes of Eluard as it is of Yevgeny Yevtushenko, a poet who woke up the California poetry scene in the 1970s. Apologists for the extreme left in Europe and North America, if they read or listened to Yevtushenko, had to realize that the Soviets (and the Maoists) had not created any kind of utopia.

“Cinderella,” Yevtushenko told us, if we cared to listen,

My poetry,

like Cinderella,

forgetting its own essential tasks,

washes, as from dawn’s first glimmer,

every day,

the soiled linen of this age.[1]

The so-called fake poems followed by Reid’s “Recollections” make this book very well worth consulting. Most of the poems repay reading and re-reading, some written in the “free” style of the Americans who avoided punctuation, and others with punctuation. All, however, have real syntax and can therefore make sense. Some are brief prose paragraphs. Among these poems there is also a complex playing with forms, where Fake Poem 18, “WHAT LIFE HOLDS,” written for Pierre Coupey on his seventieth birthday, uses punctuated but otherwise “free verse” in three sections, the third (method map, erased commentary) being lists of disparate key words followed by a black and white photo of a room with paintings, making “…a space that opens, / a mouth that speaks” (p. 57).

Fake Poem 20 on the news of slaughter and war is, unhappily, about something we know will come back onto the news almost every day, “The horror of/the news today…” (p. 59). And the poem “Where to find grace” takes us back into the everyday experiences we all know: “The water that falls from the sky/always a grace.” (p. 61) We know how precious now a democratic country is, far from war and war’s alarms.

The Recollections, essays once published in small local journals, add up to a montage of Vancouver’s version of a “bohemian” network of poets, artists, friends, and would-be major figures in the history of Canadian literature and art. The essay on Curt Lang, a pundit and almost an icon in the fifties and sixties of Vancouver, before it began in the late seventies to become the pricey, tower block city of money launderers, multi-ethnic realtors, drug dealers and drug takers, politically correct finger pointers, and, thank goodness, French pastry makers and master chefs. Looking back at these essays is salutary.

Many of the people named are forgotten, but deserve a place in the history of west coast literature and art. Margaret Atwood, who taught at UBC in 1964-65, appears as a minor figure before becoming an international literary success story in her own “write.”

It is worth reading the pieces conveniently gathered here: we are reminded that bill bissett’s blewointment lifestyle and literary, careering through the sixties and seventies, actually started in the fifties, when Reid claims bill anticipated the Beatles and Bob Dylan as a beatnik.

People who have followed Bob Dylan’s stellar trajectory will be fascinated to rediscover Reid’s essay on him, and those many of us who value Newlove’s work will find Reid’s “A Night Of Newlove” engaging, honest, and graceful itself in uncovering Newlove’s own graceful side.

These essays when first published were heady stuff, and some of their freshness remains, but for me their main value now is as a literary or artistic record of developments on the Pacific West Coast, now a very active haven for many artists and writers whose distance from Toronto is not as much of a disadvantage as it was before the efficacy of the internet. It’s still an advantage for writers and artists to live in London, New York, Paris, Berlin, but it is not so much of a disadvantage to live thousands of kilometres away from these great centres.

Anvil Books have done us a real service in bringing to light these fragments of Jamie Reid’s work for posthumous publication here.

*

Andrew Parkin was educated in Birmingham at school, and in the RAF Russian programme. After that he studied English at Cambridge and drama for a Ph.D. at Bristol. He emigrated to Canada and taught at UBC before going to the Chinese University of Hong Kong where, with the Chinese Canadian poet and translator Laurence Wong, he read at the Canadian Consulate and elsewhere on campuses. He retired to Paris and read for the Spring Poetry Festival there and in the “Poets Live” series, before returning to Vancouver with his French wife in 2015. He has been invited to read later this year in Regina and Toronto from a soon-to-appear bilingual edition of his Star with a Thousand Moons (Ekstasis, 2011). Meanwhile he is completing a trilogy of novels about counter-terrorism.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for serious coverage of B.C. books and authors, hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

[1] George Reavey (editor), The Poetry of Yevgeny Yevtushenko (London : Calder & Boyars, 1969, p. 235.