#255 Spitfire luck of Skeets Ogilvie

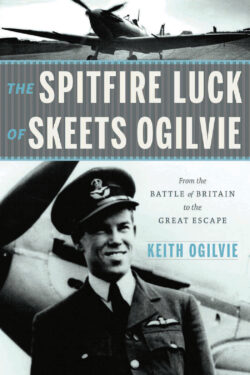

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie: From the Battle of Britain to the Great Escape

by Keith Ogilvie

Victoria: Heritage House, 2017

$22.95 / 9781772032116

Reviewed by Michael Sasges

First published Feb. 28, 2018

*

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie tells the story of two Canadians who made an ordinary life together after some extraordinary experiences. Alfred Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie (1915-1998) was an Ottawa native, a Battle of Britain fighter pilot and a “Great Escape” PoW.

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie tells the story of two Canadians who made an ordinary life together after some extraordinary experiences. Alfred Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie (1915-1998) was an Ottawa native, a Battle of Britain fighter pilot and a “Great Escape” PoW.

Skeets passed the first two of his war years at flying schools or air stations in the south of England and the last four in captivity, in Germany.

His wife, the former Irene Lockwood (1918-2014), was a Regina native and government censor and air force photographer. She passed all her Second World War years in London, where she met Skeets when he was on leave.

Skeets and Irene Ogilvie were the author’s parents.

The Spitfire Luck of Skeets Ogilvie is an audacious literary adventure for author and publisher because it is flying familiar skies and, further, flying skies that bigger authors and houses have already crossed, and crossed memorably. It is a late addition to at least three Second World War genres: personal narratives by and about Canadians, military aviation, and German prisons and prisoners, as subject searches on the Vancouver Public Library website demonstrate.

The first titles in these considerable genres were published during the war itself. Author Keith Ogilvie acknowledges his contribution to these literary categories in his foreword and in his bibliography, which numbers forty books.

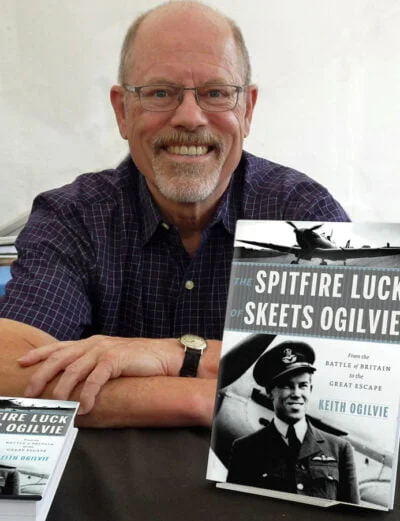

Keith Ogilvie — who takes inspiration equally from Barry Broadfoot (Six War Years, 1939-1945: Memories of Canadians at Home and Abroad, 1974) and Len Deighton (Fighter: The True Story of the Battle of Britain, 1977) — is a North Saanich resident who, in his younger years, was an aviation engineer and RCAF officer and, in his older years, a consultant to business and government.

Fortunately, Skeets Ogilvie kept a diary while learning to fly and a journal while flying in battle. The intimacy and immediacy of these, combined with personal correspondence, family photo albums, and scrapbooks, inevitably eases our engagement with The Spitfire Luck. “We” too could write a diary; “we” have had our picture taken, and some of us may be amused to read of the “rye and dry” that kept fighter pilots company in the evening after a day of finding and fighting “snappers” aloft.

Readers will quickly forget what they know of the Battle of Britain because this is a new and fresh telling, admirably sourced, textually and graphically crisp, a convincing chronicle of people making the best of trying circumstances. Keith Ogilvie’s statement of purpose is “not just to talk about the extraordinary but to celebrate the ordinary too, as being extraordinary in its own right.” He delivers.

Of all the “ordinary,” or common, activities chronicled in Skeets Ogilvie one stands out, and that is the acquisition and inculcation of the skills that permitted ordinary young men to engage in air battle over England and France, or, put another way, to do something extraordinary or uncommon.

The pace stuns. The RAF believed in learning by doing. Skeets Ogilvie soloed sixteen days after his first full day at his initial training school. “On the first circuit I bounced her and scurried across the ‘drome like a startled deer. The second landing was no hell but at least I got her down,” he wrote in his diary. “Today I am a pilot.” He flew his first sortie, and in a Spitfire, thirteen months after his first solo flight.

Between completion of initial training and assignment to the RAF’s 609 Squadron, he attended three other flying schools and one practice squadron. The aircraft were always bigger and faster. The demands on the pilot were always growing. Night flying followed on daylight flying; poor-weather flying, good-weather-only flying. Point-to-point-to-point flying replaced local flying. Formation flying, two or more warplanes in close proximity and commanded by one of the pilots, made a pilot a fighter pilot.

As a Spitfire pilot in the Battle of Britain (July-October 1940), Skeets established his credentials with six confirmed victories and several enemy aircraft damaged.

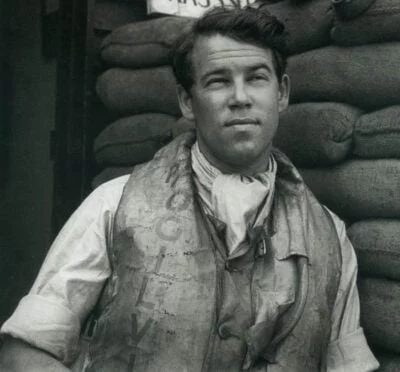

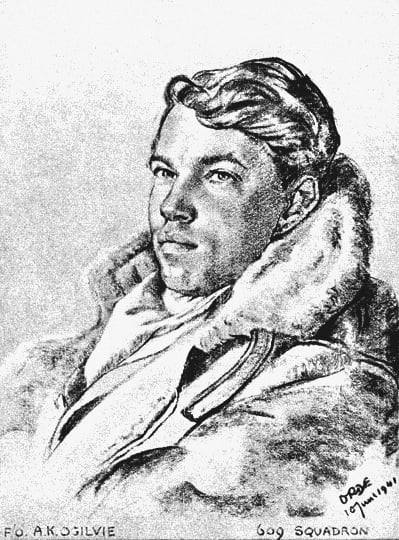

A photograph of Skeets and a drawing of him seem to capture the accolades bestowed on these young RAF pilots in their heroic endeavours.

The photographer was Cecil Beaton (1904-1980) who, in the words of the National Portrait Gallery, London, was “one of the most celebrated British portrait photographers of the twentieth century … renowned for his images of elegance, glamour and style.”

The artist was Cuthbert Orde (1888-1968). Visit enough pubs in the vicinity of an RAF station, active or closed, in the south of England and you’re bound to come across a copy or two of an Orde drawing of one of “the few.” And of those few, Skeets was one of the lucky few survivors.

In July 1941, he was in a Spitfire escorting Blenheim bombers to a chemical works and power station at Chocques, near Bethune, in France, when he was shot down by a Messerschmitt. Badly injured, he spent nine months in hospitals in Lille and Brussels being treated by German surgeons before being sent to Stalag Luft III in Poland where, in March 1944, he took part in the Great Escape.

He was at large for two days before being recaptured, interrogated, and returned to the camp. Most escapees were shot. He was liberated in April 1945 and transferred to the RCAF as a Flying Control Officer.

Skeets and Irene Ogilvie returned to Ottawa after the war and Skeets entered the jet era with the RCAF.

Fortunately Skeets and Irene were letter-writers, both to each other and to their families. (Keith’s sister, family archivist Jean Ogilvie of Ottawa, must be mentioned here).

A 1946 photograph of Irene and Keith on the porch of the Ogilvie family home in Ottawa, either newly engaged or just married, evokes, as no words can, the pleasures of peace and the promise of that long and prosperous Canadian peace that followed the Second World War.

So, yes, the ordinary can be extraordinary.

Waiter, a “rye and dry” if you please for Skeets and Irene Ogilvie.

*

Mike Sasges is a retired Vancouver newspaper editor and reporter forever envious of an older, by thirty years or so, colleague, ex-RCAF, who many years ago, actually or apocryphally, responded to the question, “Ever been to Germany?” with the answer, “Only from 30,000 feet.” Mike Sasges has an MA in Graduate Liberal Studies at Simon Fraser University.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster