#218 One dammed river before another

People, Power, and Progress: The Story of John Hart Dam and the Campbell River Power Projects

by Daniel Stoffman

Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2017

$24.95 / 9781927958384

Reviewed by James Hull

Co-published with the BC Hydro Power Pioneers.

First published Dec. 11, 2017

*

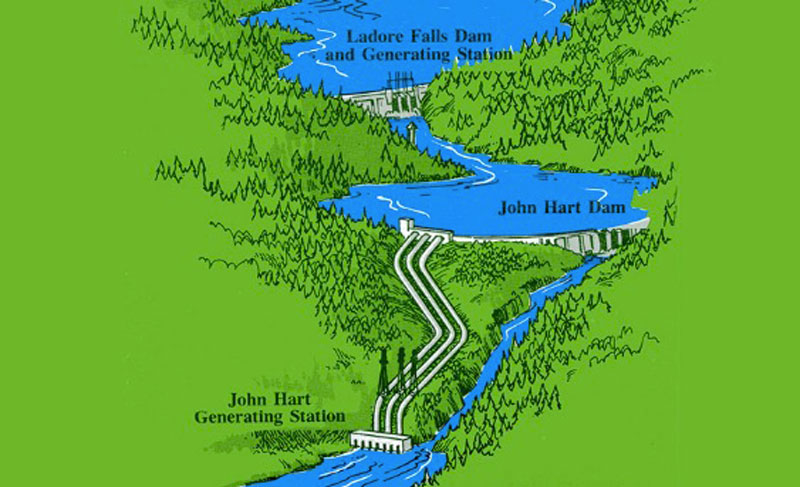

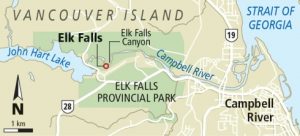

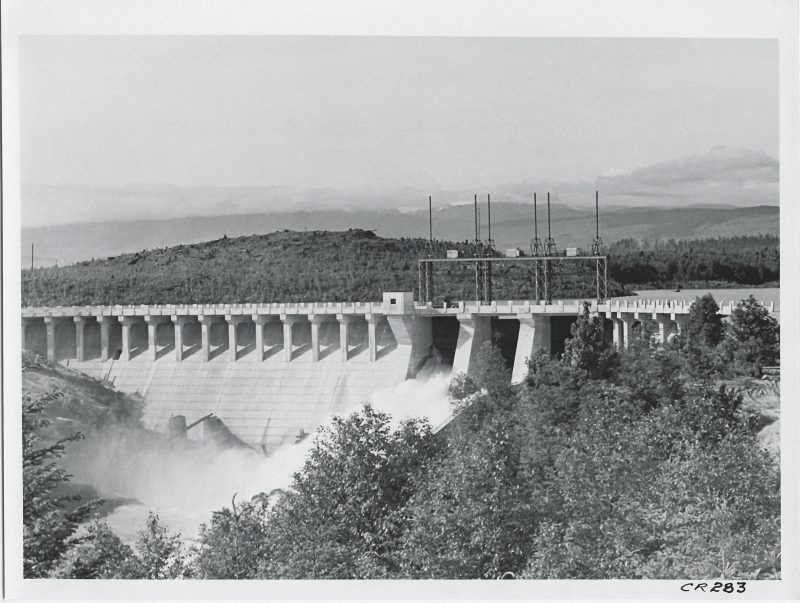

The John Hart Dam and generating station opened in December of 1947 as the biggest and lowest of three developments impounding and using water from Upper Campbell Lake on Vancouver Island on its way to the Strait of Georgia.

The John Hart Dam and generating station opened in December of 1947 as the biggest and lowest of three developments impounding and using water from Upper Campbell Lake on Vancouver Island on its way to the Strait of Georgia.

The dam created John Hart Lake in the logged-off timber properties between the strait and the Vancouver Island Mountains.

Named for John Hart, premier of B.C. from 1941 to 1947, it formed part of a policy of post-World War Two resource-based development promoted by the provincial government. Future Premier W.A.C. Bennett, architect of what has been called “Big dam government,” was enthusiastically involved as a member of the John Hart’s post war Rehabilitation Council.

While residents of the town of Campbell River would benefit from the development, it was especially intended to supply power for pulp mills on the Island with the Bloedel, Stewart & Welch pulp mill at Port Alberni a major customer.

As an economic development strategy there was nothing very innovative about this; Ontario had followed the same path a generation earlier. Indeed the project would be built by Ontario-based H.G. Acres Co., which had been involved in hydroelectric development at Niagara Falls.

Though dwarfed by later mega-projects, the John Hart Dam was in its day a very significant undertaking for B.C.’s provincial State. It was also part of post-war planning to extend electric power to previously unserviced rural areas under the slogan “a bulb in every barn.”

Though dwarfed by later mega-projects, the John Hart Dam was in its day a very significant undertaking for B.C.’s provincial State. It was also part of post-war planning to extend electric power to previously unserviced rural areas under the slogan “a bulb in every barn.”

The B.C. Power Commission’s activities would also help to provide jobs for graduates of UBC’s engineering programmes, many of whom had been going off to greener pastures in Ontario.

After a seventy-year life, the John Hart station is currently slated to be replaced in an ongoing billion dollar project, among other reasons to meet contemporary seismic standards, this time with Quebec-based SNC-Lavelin as the contractor.

To a degree the book’s title, People, Power, and Progress, says it all, offering an easy conflation of infrastructural development with progress. The author is not an academic historian but a writer on a variety of public policy topics, perhaps best known for his pop-demographic Canadian bestseller Boom, Bust and Echo: How to Profit from the Coming Demographic Shift (Macfarlane Walter & Ross, 1996, co-authored with David Foot).

Based on a blend of secondary and primary sources including reminiscences of those involved in the project, the organization of People, Power, and Progress is loosely chronological but with various asides and dips back to trace particular topics.

Sidebars include the bizarre story of proposed cloud seeding to increase rainfall for hydro purposes and a somewhat irrelevant re-telling of the Ripple Rock story.

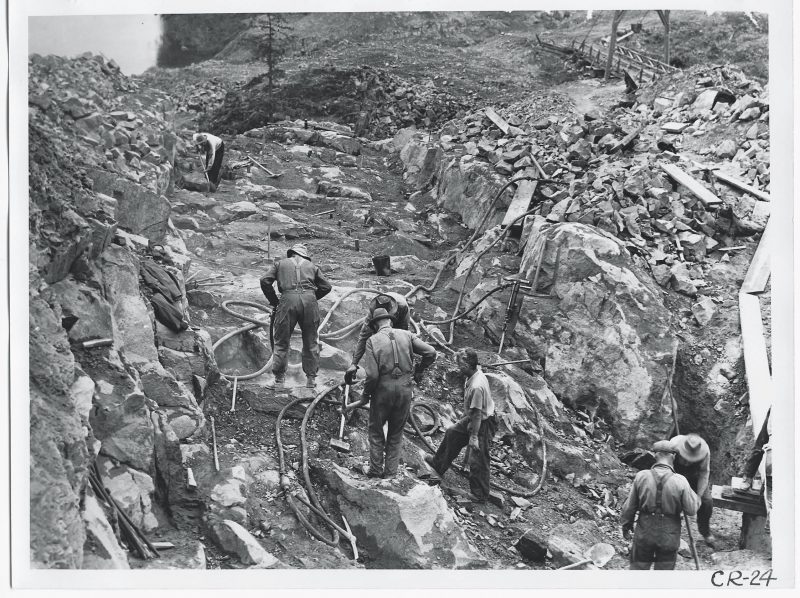

People, Power, and Progress is an easy if not always absorbing read, with technical matters dealt with clearly where they need to be. Indeed historians of technology might like to know a bit more. For example, we are told on one page that concrete for the dam was made on site, but then on the next page that delays were occasioned by “the inability of the project’s machinery to handle the type of cement that had been supplied” (p. 41).

The book is one of several historical and commemorative volumes sponsored by ex-BC Hydro employees, the “BC Hydro Power Pioneers.” It is likely that they and long-time Campbell River residents will be the most enthusiastic and interested readership; few under retirement age may know who Susan Hayward was, or care why she was a tourism visitor.

While not entirely uncritical, the book’s conclusion in advance is that the project is a “classic example of how water power can co-exist with other traditional land uses while providing emission-free, renewable energy” (p. 7).

Stoffman acknowledges that the conflict between economic growth and environmental protection was an issue from the start. But also, from the start, protection had an economic dimension. After all this is British Columbia, and we know those fish aren’t in the Campbell River to be admired; they are there to be caught for sport and as trophies.

Roderick Haig-Brown was a redoubtable advocate of the environmental side — but also a redoubtable Nimrod of the fly fishing rod. The impact of the project on recreational fishing, and on the revenues it brought in, has been a perennial issue.

Interestingly, one of the great also-rans of Canadian history, H.H. Stevens, identified in this book only as a former federal Conservative cabinet minister, shows up as an opponent of the associated Buttle Lake Project and an advocate of environmental preservation.

Stoffman mentions that the federal government was involved too in the form of Fisheries and Oceans Canada; it would be good to learn more about the relationship of the Provincial and Federal actors.

If, however, you want to understand the environmental impact of hydro development on river fish stocks, you would do better to read the volume edited by James Ward and Jack Stanford, The Ecology of Regulated Streams (Plenum Press, 1979) or Matthew Evenden’s Fish versus Power: An Environmental History of the Fraser River (Cambridge University Press, 2004).

Also, as the John Hart dam has provided power to the forest products industry, the environmental impact is not just direct but also indirect via logging. The problems have not gone away. Indeed in the description of these particular dams vs preservation battles there is a real sense of “Plus ça change…” After diverting more or less all water from Elk Falls, since the 1990s BC Hydro has been required to send some over the Falls for aesthetic and tourism purposes.

While not an environmental whitewash, the book’s emphasis is on ameliorative initiatives and the benign nature of hydro power as renewable and emission free. Presumably BC Hydro is not responsible in any way for emissions and effluents from its pulp mill customers.

Social and labour historians will also note, by its absence from the book, any engagement with issues of class. At least some of the work force was unionized and a brief allusion is made to labour strife. But strikes are pesky things that interfered with construction by restricting the availability or lumber and steel. The impact on employees of the automation of hydro operations is dismissed in a paragraph. Similarly the stories of idyllic family life in the “Hydro Hollow” residential area for employees give no suggestion of class tensions.

This volume gives a nod of thanks early on to First Nations. Later they show up as original inhabitants, exploiters of salmon resources, advocates of preservation, project employees, and fishing guides. That is all to the good but it would have been helpful to have had the changing economic contexts of Indigenous Vancouver Island societies explained in some more detail.

As it is we have to be satisfied, or dissatisfied, with the author’s solemn assurance that BC Hydro’s “relationship with the region’s First Nations has become one of cooperation and mutual respect” (p. 126).

Commissioned commemorative histories as a genre tend to be long on celebration and short on analysis. But they can be done well and do good history; I think of Jeremy Mouat’s centennial history of West Kootenay Power & Light, The Business of Power (Sono Nis Press, 1997), as an especially good example.

All in all, with Daniel Stoffman’s People, Power, and Progress, the Hydro Pioneers have got their money’s worth. This handsomely produced and lavishly illustrated volume will help keep the historical memory of the original John Hart project alive. It will also be a helpful point of departure for any future academic study.

*

James Hull is a member of the Department of History and Sociology at the Okanagan Campus of the University of British Columbia. Former Editor-in-Chief of Scientia Canadensis, he has published dozens of articles and book chapters on topics ranging from the history of industrial research to Canada-US economic integration. He is currently working on a study of British Columbians’ responses to the Canadian Manufacturers Association’s “Made-in-Canada” campaign.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster