#212 Our vanishing glaciers

First published Nov. 29, 2017.

Our Vanishing Glaciers: The Snows of Yesteryear and the Future Climate of the Mountain West

by Robert William Sandford

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books 2017.

$40 / 9781771602020

Reviewed by Clayton Whitt

Melting glaciers and climate change may initially seem like odd topics for a coffee table book. But when you open the cover of Robert William Sandford’s Our Vanishing Glaciers, a tome replete with scores of full-colour photographs and a couple of hundred pages of commentary on western Canada’s changing glaciers, you might wonder why no one has done it before.

Our Vanishing Glaciers arrives in a world that is drenched in climate change commentary but still facing a severe shortage of the public outcry and political willpower needed to curtail carbon emissions. By moving Canada’s melting glaciers onto Canada’s coffee tables, the book aims to bring concern over this pressing issue to a broader audience in a mainstream and accessible format.

But it also aims for more: it is a poetic pilgrimage through water’s near-miraculous vitality and an exploration of the interconnections engendered by water that link the earth and human bodies together. In the words of Sanford, “The water within us feels the tug of the tide” (p. 13).

In telling the story of western Canada’s glaciers, Our Vanishing Glaciers starts at the beginning: not with the last ice age, but even more essential, with the nature of water itself. Unfolding over the first three chapters, the basics of water and its various stages come to life at the point of Sandford’s pen, as he describes water’s material interconnections with the Earth and its organisms.

In his vivid early descriptions of water, Sandford de-familiarizes this common substance for his readers, encouraging them to step back and admire its diverse and under-appreciated properties and uses, from nourishing our bodies to shaping the climate. Discussing the role of water in sculpting the surface of the Earth, Sandford notes with wonder that there are marine fossils on top of Mt. Everest. As he puts it, “The conversation between water and landforms never seems to end” (p. 23).

Given the theme of the book, it is no surprise that Sandford takes a special interest in water’s transformations under the cold of Canadian winter, building up to its congelation in the ice that forms Canada’s glaciers and ice fields. Still, he takes the time to discuss the lesser known events of freezing, such as the frogs that, in passing the wintertime in a frozen state, “give themselves up to the cold of death and enter an outer space that exists at the inner heart of the winter world” (p. 55).

Although Sanford waits until Chapter 4 to get into the details of the titular glaciers, the long buildup provides the kind of deeply contextualized view of water and its processes that is needed to fully understand the stakes of climate change.

In the book’s middle part, he gets into the details of Canada’s major bodies of ice, their central role in Canada’s hydrology, and key glaciological studies from over the years. There is a lot of ice to cover here, and in order to do so this portion of the book takes on a more matter-of-fact tone than the previous chapters, which was a minor disappointment to this reader.

In relating different histories and studies of Canada’s most charismatic glaciers, particularly those of the Columbia Icefields, Sandford tells a tale of interconnection — of the deep relations between places, water, landscape, and atmosphere that form the Canadian Rockies as we know them today and even influence many Canadians’ sense of identity.

It is a masterful tale, but I was struck that the book would have benefited from more discussion of local knowledges and histories from the original inhabitants who have had long relationships with North America’s glaciers. At the end of Chapter 4, Sandford does discuss the anthropologist Julie Cruikshank’s work with the Tlingit of northern British Columbia and the Yukon in Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination (UBC Press, 2005), and he considers the relationships between different types of knowledges about the glaciers.

This is an important part of how Sandford presents the links between glaciers and people, but it is too limited, and I would have loved to see consideration of such Indigenous knowledges incorporated more into other parts of the book.

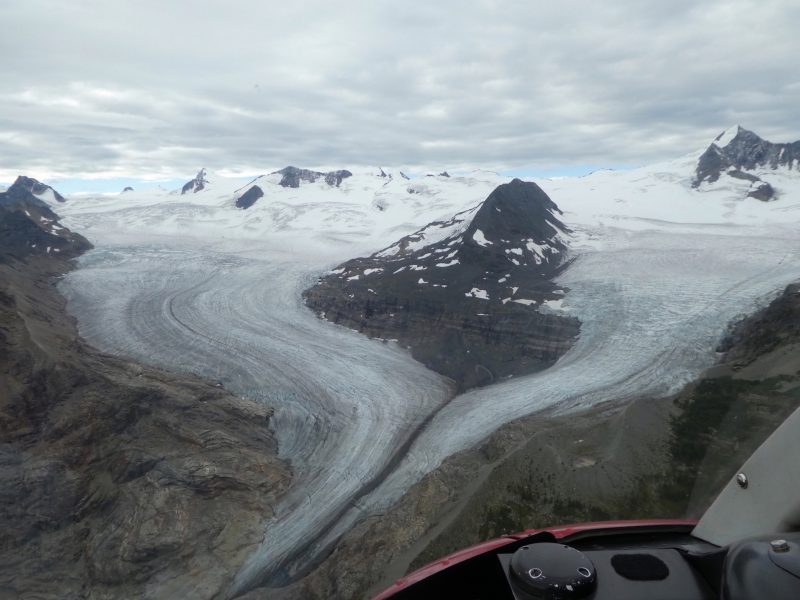

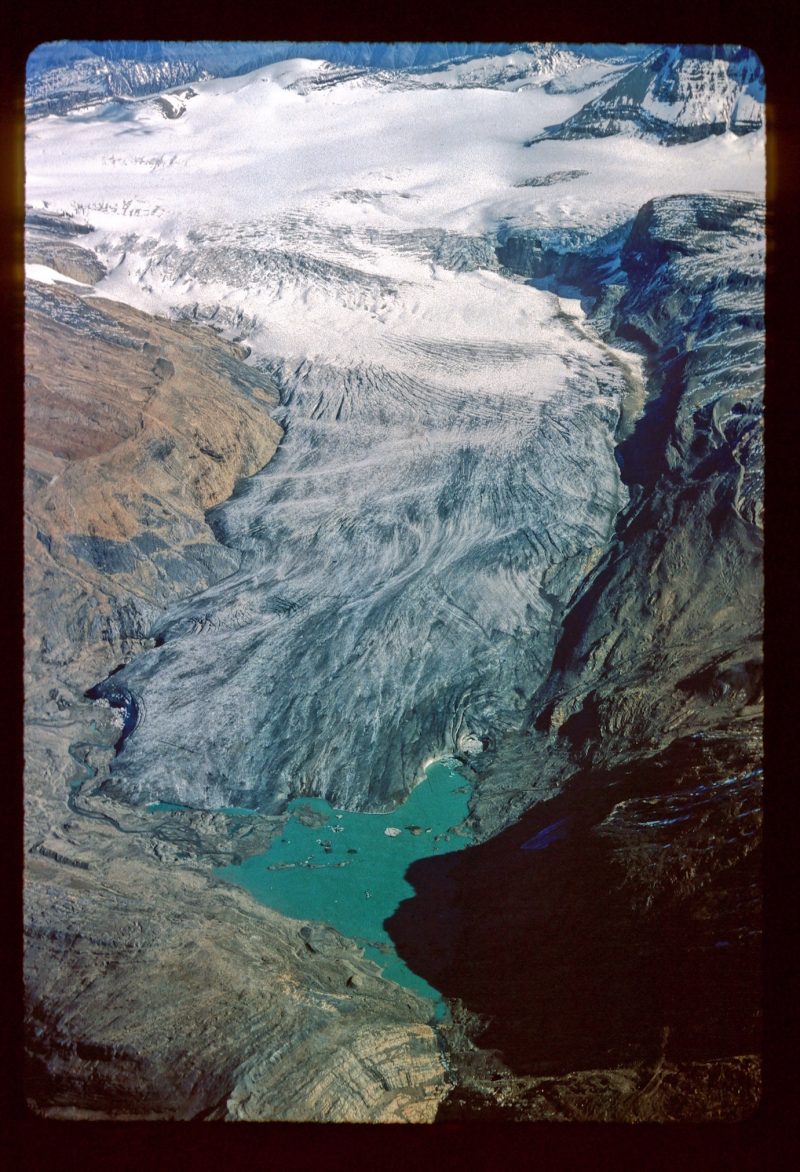

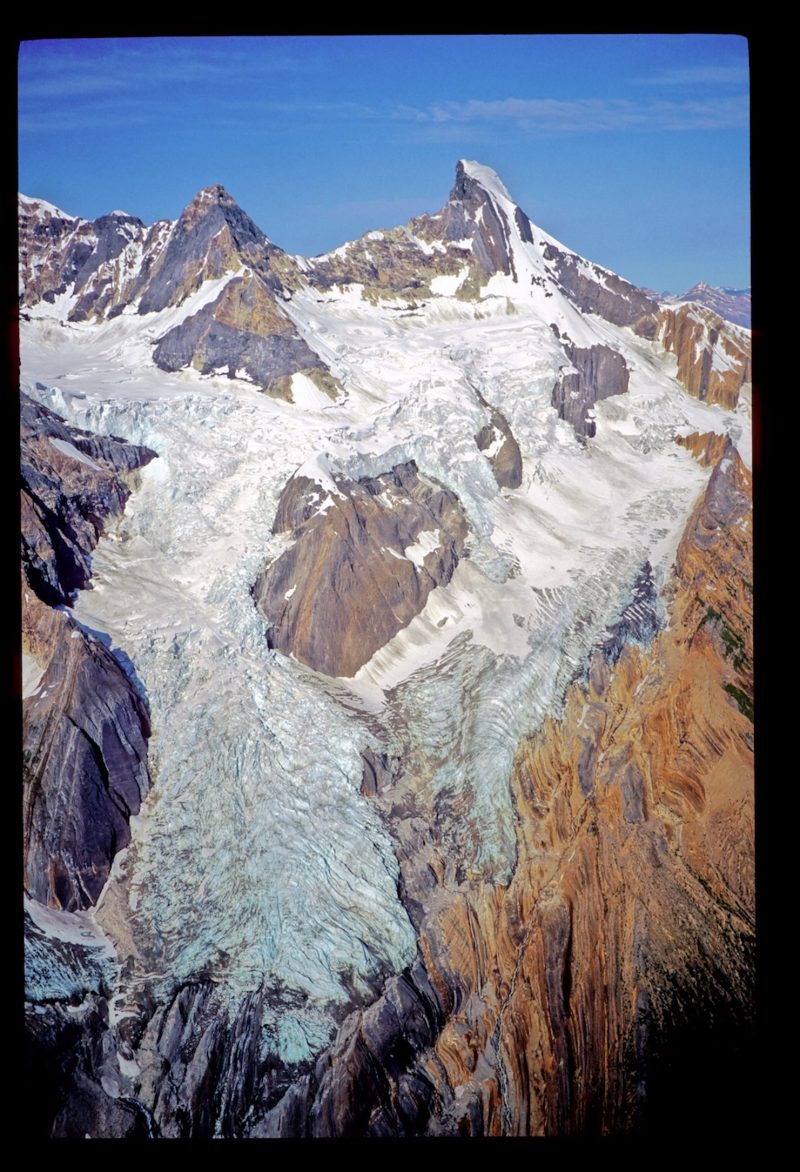

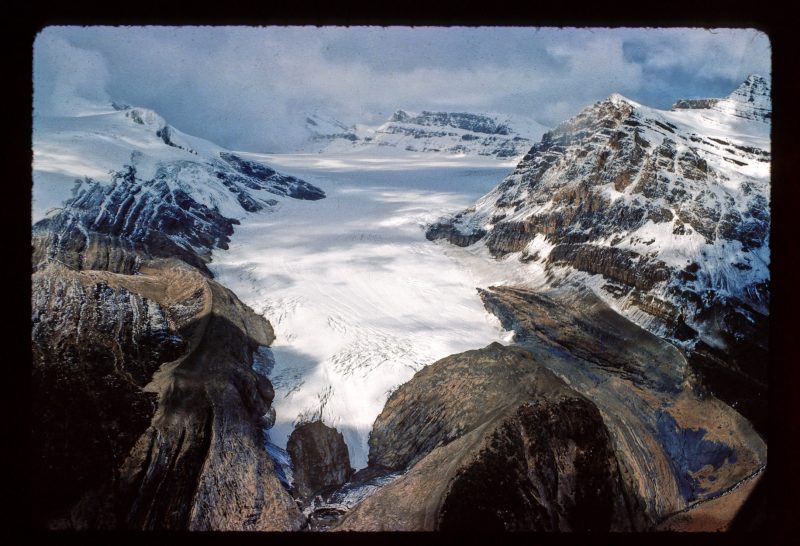

As a large-format book (27.5 cm x 22 cm), obviously one of the primary missions of Our Vanishing Glaciers is to deliver beautiful, full-colour photographs of some of western Canada’s most striking glaciers and icefields. Both iconic ice bodies and hidden icy gems are well-represented in the pages, with historic and comparative photos as well as contemporary aerial views and on-the-ground snapshots from scientific expeditions.

The presentation of photography is used to great effect to exemplify how processes of recession manifest in glacial bodies, such as in a series of images in a later chapter entitled “What We Stand to Lose” that catalogues major glaciers in the Canadian Rockies and how they are suffering retreat. This photo array goes hand-in-hand with a vivid description of what the mountains around the Icefields Parkway, which links Lake Louise with Jasper National Park, may look like in 2100.

In Sandford’s words, projecting what it will be like to look upon the bare mountains, thin streams, and diminished mountain lakes of the future, “You find yourself speechless with a different kind of awe” (p. 184).

It is this “different kind of awe” that runs through the last few chapters of the book and highlights one of the book’s standout points, which is Sandford’s concern about the embodied experience of glaciers: in short, how the icefields make you feel. Some authors who managed to communicate so many of the finer details of glaciological research may have disregarded this dimension as too sentimental or subjective, but Sandford aims for a holistic view of glaciers and achieves a balance between pathos and logos that gives the book much of its persuasive power.

Sandford understands that caring about glaciers encompasses a lot more than just knowing scientific details; caring is also a visceral, bodily state, much like the sense of awe that strikes someone seeing the Athabasca Glacier at the foot of Mt. Andromeda for the first time.

The undercurrent of Our Vanishing Glaciers, then, is this invitation to the reader to care from the heart for Canada’s glaciers under climate change, to try to save them, or, at the very least, to love them before they are gone.

*

Clayton Whitt is a cultural anthropologist who lives in Vancouver. He studies people’s experiences with and responses to climate change and other environmental problems in the Bolivian Andes. His latest worked is centred around Bolivia’s Lake Poopó disaster of 2015, when an entire lake in the Andean highlands dried out after years of pollution, water diversions, and climate shifts.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster