#183 Modernist poet Blaise Cendrars

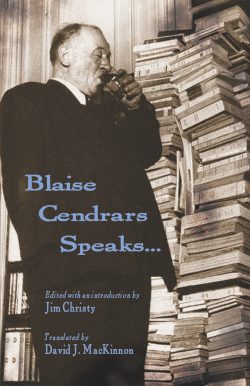

Blaise Cendrars Speaks…

by Blaise Cendrars. Edited and with an introduction by Jim Christy, translated by David J. MacKinnon

Victoria: Ekstasis Editions, 2016

$24.95 / 9781771711906

First published in Paris by Denoël, 1952 and 2016

Reviewed by Serge Alternês

Review first published Oct. 16, 2017

*

This upcoming Remembrance Day we might recall and commemorate Blaise Cendrars (1887- 1961), the disabled First World War author-veteran whose right arm was blown off in the Somme in 1915. In convalescence he taught himself to write with his left hand, creating a literary tour de force that transformed poetry and literature forever. — Ed.

This upcoming Remembrance Day we might recall and commemorate Blaise Cendrars (1887- 1961), the disabled First World War author-veteran whose right arm was blown off in the Somme in 1915. In convalescence he taught himself to write with his left hand, creating a literary tour de force that transformed poetry and literature forever. — Ed.

*

Blaise Cendrars Speaks presents a remarkable set of interviews done in Paris in 1950 by Michel Manoll of Radio France with the Swiss-born French author Blaise Cendrars.

In this long-awaited English translation of what is by far the best introduction to the vast scope of Cendrar’s oeuvre, the modernist Blaise exudes his joie de vivre, his eternal wanderlust to travel, and the compelling urge to explore and perfect his writing. Shy behind his mask, he weaves fantastic legend with his life and then digresses into the labyrinth of his mind.

These improvised and spontaneous interviews concerning Cendrars’ life and work in the first half of the twentieth century reach to the origins of his far-reaching impact.

Cendrars elaborates on his new poetry with his poet colleague Apollinaire, critiques the movements of the painters Picasso, the Delaunays, Léger, and Chagall, describes his reporting in the great conflicts of the twentieth century (the First World War, the Spanish Civil War, and the Second World War), and outlines his new approach to cinematography, novels, and the masterful autobiographical prose of his later years.

He recounts the extraordinary times he lived in, including Paris at the turn of the century, the birth of the Trans-Siberian railway, the Cubist and Surrealist movements, the horrors of war from the perspective of a disabled war veteran, and the eve of the Russian Revolution.

His wide-ranging anecdotes include the birth of spoken film in Hollywood, his own dabbling in a myriad of trades from jeweller to bar pianist, and his own relentless steamship travel to the ports of the world, including Vancouver, which gave birth to a pre-1914 poem. It reads in part:

That lurid spot in the dank darkness is the station of the

Canadian Grand Trunk,

And those bluish patches in the wind are the liners

bound for the Klondike, Japan, and the West Indies.

(translation by Monique Chefdor).

One beautiful description and translation from Blaise Cendrars Speaks shows the unforgettable links between a grandiose ocean life and a steamer’s path back to Paris:

An impression of lightness, of agility, of vivacity. A whale that comes to play around a boat dives, tacks, sprays, and sprouts foam, passes from port to starboard, scratches his back against the keel. It’s an extraordinary spectacle, and when you reflect on the speed at which this enormous mass swims, and the grace with which it swims and dives. On a fair day, a pod of whales gliding across the path of a trans-Atlantic passenger liner in a convoy has all the appearances of a royal gala. Imagine the grand fountains of Versailles, a thousand spouts of water, a thousand wakes unravelling like ribbons, an entanglement of ripples, the sky aquamarine like an engraving.

His wanderlust is complemented by his love of music and for the ordinary peoples around the world, particularly in Africa, Brazil, and the nomadic Romani gypsy folk.

i. “Je suis l’autre” (I am the other one)

Have you ever wondered what it was like to get a first publication a century ago, or a first art showing? What is it like to be a train robber, an assassin, a whaler? Or if writers and painters have always been rivals of each other, or who could ever steal the Mona Lisa, or the origins of Picasso’s fame, or how Chaplin was perceived in his time, or what Hollywood was like in the thirties at the birth of spoken film, or why Walt Disney was the most remarkable “assembly-line poet”?

You will find answers to these and many more questions in the amusing and often mocking anecdotes of Blaise Cendrars Speaks. He is a compelling author to discover. The more you read of Cendrars’ works, the more questions you will have with his trailblazing breaking of taboos.

To understand better the background of this book, we can start with an odyssey through Cendrar’s life and work. Frédéric-Louis Sauser was born in 1887 in the French-speaking Swiss Jura watchmaking town, Chaux-de-Fonds, taking on his nom de plume Blaise Cendrars in 1912.

Freddy was always bursting at the seams. This eternal phoenix chose his pen name to evoke braise or ember in French, and cendres or ashes, and art in French; the final “s” and “t” are not pronounced.

His entrepreneur Anabaptist father and Scottish mother could not contain or understand him. Sending him to Swiss German boarding school where he became known as “Fritz” only aggravated his growing alienation. He escaped Switzerland as an eloping young sixteen-year-old by taking an eastbound train to Moscow.

One his early mentors, Goethe, wrote in his autobiography Aus meinem Leben: Dichtung und Wahrheit: (From my Life: Poetry and Truth):

Und so begann diejenige Richtung, von der ich mein ganzes Leben über nicht abweichen konnte, nämlich dasjenige, was mich erfreute oder quälte, oder sonst beschäftigte, in ein Bild, ein Gedicht zu verwandeln und darüber mit mir selbst abzuschließen, um sowohl meine Begriffe von den äußeren Dingen zu berichtigen, als mich im Innern deshalb zu beruhigen.

And so began that direction from which I could not deviate all my life, that which pleased or tormented me, or otherwise occupied me, in a painting, to transform a poem and to reach closure with myself, in order to correct both my concepts of external matters, and to appease my inner self. (Translation by book reviewer).

Not finishing his Baccalaureate at the end of high school, Freddy became an eternal student of life. After French and German in school, he learned Russian, English, Brazilian Portuguese, Spanish, and Romani.

Young Freddy’s genius was perceived by very few, among them a mysterious Russian librarian R.R., and later a fellow student at the University of Bern — his first wife, Féla Poznanska, with whom he had three children the following decade. That decade also saw Cendrars volunteering with the French Foreign Legion in the First World War, apparently to avoid deportation from France and to become a French national.

One of his children, Miriam Cendrars, presently 97 years of age, has perpetuated Cendrars’ work in the Centre d’Etudes Blaise Cendrars (CEBC) in Switzerland. Like her father before her in the Great War, during the Second World War she joined the French Resistance in London where she had a radio programme addressing the children of Free France in Babar, éléphant français libre.

Cendrars’ road was a long one. Initial recognition by fellow writers and painters was followed by literary critics and finally the French literary establishment and “La Pléiade.” His self-defining phrase Je suis l’autre is interesting in our bilingual Canadian context where the vous autres English-speaking Canadians should be inspired by Cendrars to be different and not like “cookie cutter” New Yorkers. In Blaise Cendrars Speaks, he describes New York as the most hilarious place:

But it’s life, day-to-day life, the appearance of people in the street, the conception of people who all follow the same cues. You can see it in their facial expressions. People who all think the same thing. People who all read the same newspapers and who all look so contented. In the subway, they’re all dressed the same way, as if they came off the production line. Based on their clothing, their outer appearance, you can know where they live. You can calculate their subway stop. You can figure out their trade, how much they earn, whether they are living too high on the hog, their neighbourhood or borough. It’s amusing no end.

ii. “Partir” (To depart). Il faut partir pour bourlinguer… mais ne jamais arriver (one must depart to vagabond… but never get there.)

Cendrars’ poetic heritage came from the French poets Villon, de Nerval, Baudelaire, Verlaine, and Rimbaud. The writing and philosophy of Goethe and the criticism of the Symbolist author de Gourmont, his literary mentor and touchstone, goaded him into the eternal perfection of his art of writing. He was fluent in Russian, writing and publishing his first poem in Tsarist Russia, “Légende de Novgorod” translated by R.R., of which only fragments have been found.

Cendrars describes the birth of modernist poetry in the interviews. His last rhyming poem “Les Pâques à New York” (1912) under his newly-adopted pen name, started the break of modernist poetry with the soon-to-follow “La Prose du Transsibérien et la Petite Jehanne de France,” which was published with the painting of Sonia Delaunay-Terk.

I recently discovered Cendrars in the Madrid Reina Sofia Modern Art Museum behind the commotion of an exhibition on the origins of Guernica, where his “simultaneous poem” is exposed as a two-metre scroll with Delaunay’s painted illustrations. Try googling this illustrated poem — “La Prose du Transsibérien et la Petite Jehanne de France” — and look at the scroll sideways, and you will see a new world starting with the lying down Eiffel Tower, followed by the wheels heading westward and ending, fittingly, in British Columbia’s south coast.

These poems announced the birth of modernist poetry with a firing blaze and a clarion. American authors such as Lawrence Ferlinghetti and the Beat Generation — as personified by his venerated San Francisco City Lights bookstore, Henry Miller, and John Dos Passos, an early English translator of Cendrars — followed Cendrars’ mind-opening path.

A later poem, “Orion” (1928) concerns Blaise’s severed right hand, with which he had written his early poetry. After its loss in 1915, his left hand became his “main amie,” which he nurtured into the apprentice of his mind. “And so I left Paris,” he confided. “I abandoned poetry. I had survived the war and now I wanted to live.”

Cendrars’ pen evolved from poetry to art criticism, to collecting cultural anthologies, to prose fiction, film scenarios, journalism, and finally to semi-fictional autobiographical prose.

Once again he bolted from the Parisian literary-artistic coterie to discover the “others” in Brazil, Africa, and the Romani Diaspora encampments. This eternal adventurer found lasting inspiration in African folklore and oral stories throughout Africa in Anthologie nègre (1921), and he gave European children’s literature a postcolonial perspective thanks to his pioneering work Petits contes nègres pour les enfants des blancs (Little Black Stories for Little White Children) (1928), which made a real renaissance at the turn of the present century in the French-speaking world, seventy years after its initial publication, forty years after its initial German publication, and a decade after the Portuguese version.

Once again he bolted from the Parisian literary-artistic coterie to discover the “others” in Brazil, Africa, and the Romani Diaspora encampments. This eternal adventurer found lasting inspiration in African folklore and oral stories throughout Africa in Anthologie nègre (1921), and he gave European children’s literature a postcolonial perspective thanks to his pioneering work Petits contes nègres pour les enfants des blancs (Little Black Stories for Little White Children) (1928), which made a real renaissance at the turn of the present century in the French-speaking world, seventy years after its initial publication, forty years after its initial German publication, and a decade after the Portuguese version.

The collaboration between Cendrars and the Brazilian poet Oswald de Anrade, and the painter Tarsila do Amaral, gave a significant inspiration to Brazilian early modernism with Brazilian artists and writers discovering their own national African-European roots.

iii. “Blessure-Reparation” (wound-healing).

Cendrars’ hypnotic prose made a new approach to the novel with works such as Or (1925) (later a Hollywood film, Sutter’s Gold) and Moravagine (1926).

It is unfortunate that his journalistic account about Spain during the second month of its Civil War was never published. His article was considered not political enough. In the interviews, Cendrars describes how the Gestapo raided his home near Paris during the war after which he secluded himself to Aix-en-Provence.

Cendrars’ last and final escape was from himself. This period gave birth to his magisterial tour de force four-tome autobiography starting with L’Homme foudroyé (The Shattered Man) of 1944.

Alas, he would never complete a project very close to his heart concerning the mystical life of Mary Magdalene in Provence, for which he chose the title La Carissima, having resided where countless legends relate that she lived during the last decades of her life as the Thirteenth Apostle.

As authors, both MacKinnon and Christy perfectly understand Cendrars, who was a major inspiration in their own novels and poetry. Blaise Cendrars Speaks flows in “politically correct” contemporary idiomatic North American English. It is interesting to note that this is also the case for Graham Good’s translation of Rilke’s Late Poetry (2004). Both of these splendid modern translations of significant European literature — of Cendrars and Rilke — hail from the shores of the Salish Sea, as many poets prefer to call it. (Incidentally, a brawling Cendrars once came to blows with the pacifist Rilke at the Closerie de Lilas in Paris).

In today’s world of machine translations it is extremely difficult to get a good translation of a literary work. David MacKinnon has made an excellent translation of Blaise Cendrars Speaks while contemporizing the content half a century later with the re-editing of the interviews and a thought-provoking introduction by Jim Christy.

*

Serge Alternês is an award-winning Canadian and French author, born and raised in Vancouver. After completing his degree at UBC, he lived and worked in France, South Africa, and Croatia. After a forty-year search for his father’s (Alec Wainman) 1,650 photos of Civil War Spain, he is delighted to be able to share this unearthed history with readers around the world. In his book Live Souls: Citizens and Volunteers of Civil War Spain (Ronsdale, 2015), the people of the Spanish Civil War come alive in humanitarian Quaker volunteer Alec Wainman’s memoir and compassionate photographs. This International Independent Publisher IPPY Award-winning book offers a stirring account of the opening act of WW2. The Catalan Live Souls: Fotos Inèdites de la Guerra Civil (2016) and the recent Spanish Almas Vivas: La Guerra Civil Española en imágenes (2017) have received much Spanish and international acclaim. Serge divides his time between Vancouver and Europe presenting his books and the Wainman Collection of photographs, in which new discoveries of international volunteers and Spanish citizens are made weekly, resurrecting their life stories. He tweets @SergeAuthor and in Facebook can be found at Serge Alternês. See also:

http://bcbooklook.com/2016/12/02/56-a-quaker-in-the-spanish-civil-war/ http://bcbooklook.com/2015/11/02/the-english-suitcase/

http://bcbooklook.com/2016/03/09/176-alec-wainman/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg — BC BookWorld / ABCBookWorld / BCBookLook / BC BookAwards / The Literary Map of B.C. / The Ormsby Review

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster