#181 Mousewoman meets Spandex

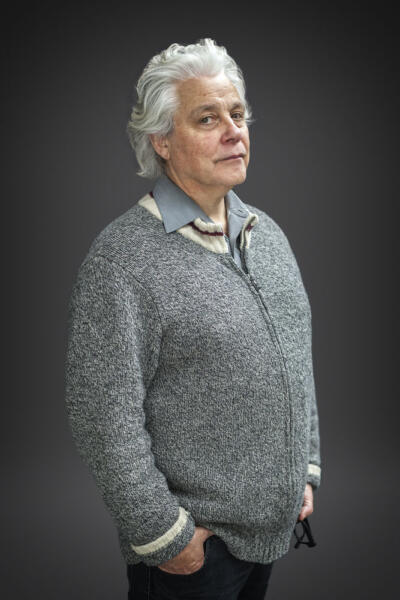

The Seriousness Of Play: Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas

by Nicola Levell

London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016

£19.95 (U.K.) / 9781910433119

Reviewed by Eldon Yellowhorn

First published October 14, 2017

*

Play, playful, and playfulness best describe the visual jazz that Nicola Levell presents in her portrait of Michael Nicoll and the Yahgulanaas experience.

Play, playful, and playfulness best describe the visual jazz that Nicola Levell presents in her portrait of Michael Nicoll and the Yahgulanaas experience.

After a short preface by Cambridge scholar Jonathan King, Levell brings to light Yahgulanaas’s work and story in five chapters following the introduction.

A practical guide and a tour of the artist’s roots in Haida culture, Chapter 1 explores Yahgulanaas’s backstory from his early years – he was born at Masset in 1954 — and lists the people and things that influenced his imagination. His maternal lineage fills a long paragraph, whereas he sums up his paternal ancestry in one sentence, mainly to explain his surname.

Yahgulanaas is Haida, a fact expressed through his art and his apprenticeship with his famous mentors, Robert Davidson and James Hart. Under their tutelage he cemented his reputation and set down the foundation for his eclectic career. Rather than follow the beaten path of carvers and painters before him, Yahgulanaas embarked on an unconventional interpretation of customary motifs.

Chapter 1 follows his transformation from a young artist intent on following tradition to an independent and creative activist and contemporary artist absorbed in iconoclasm. Popular art and novel media spread a smorgasbord of possibility before him that brought forth works such as Squids (2011).

As with boys everywhere, comic books were Yahgulanaas’s favourite literature, and cartooning, was the persistent mote that settled in his mind’s eye. Before long, superheroes and their whimsical kin abandoned the small squares of their storyboard to inhabit the open and fertile landscape in his imagination alongside the magnificent icons of Haida mythology.

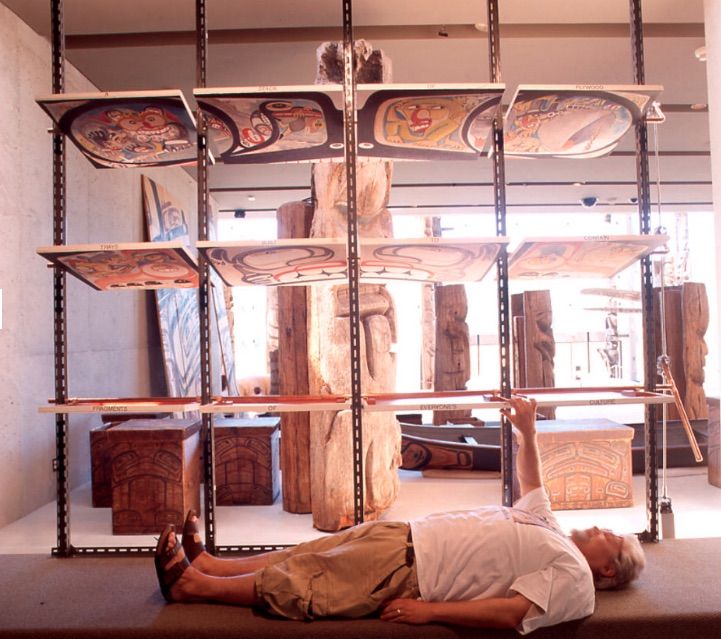

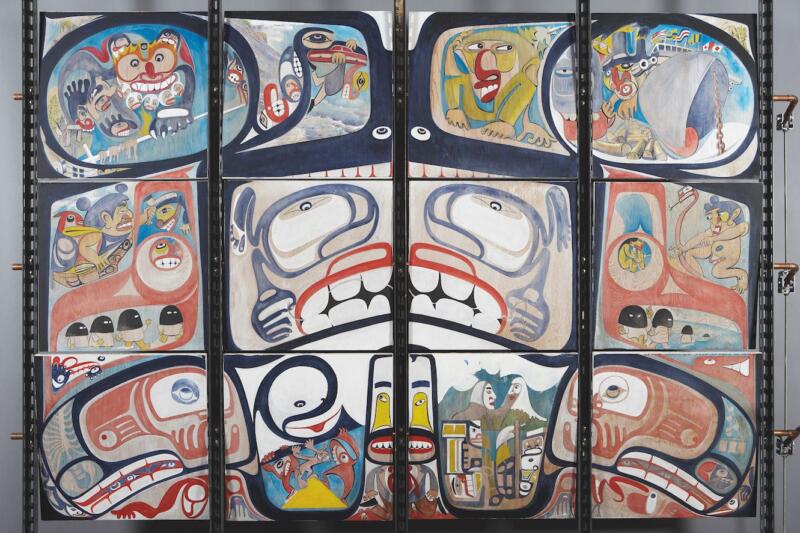

In Chapter 2, Levell explores the blended narratives that emerged from mixing expressive styles with old motifs, such as his Bone Box (2007) at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology. Channelling surrealist attitudes to animate ancient protagonists serves to bring them into the urban landscape as citizens who openly exclaim their commentary and critique of the modern world.

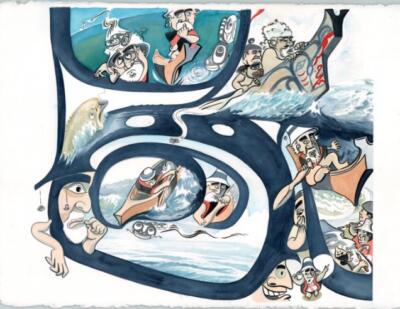

Chapter 3 chronicles the ensuing altered states of expression produced when Yahgulanaas cross-pollinated the artistic lineages of the north Circum-Pacific to create The War of the Blink (watercolour, 2006).

Heroes and their exploits have long entertained and educated young listeners, and the art of cartooning turns Yahgulanaas into a narrator who develops the plot and helps the story of his book The Last Voyage of the Black Ship (Western Canada Wilderness Committee, 2002) unfold, and in the process Haida legends gain a manga sensibility with which to wag their tales for this generation of fanboys.

Chapter 4 puts new meaning into the phrase coined by Marshall McLuhan that the medium is the message. Praising both ancient and industrial metal, Yahgulanaas’s repurposed copper designs adorn automobiles (Coppers from the Hood series, 2007), extravagant public art (Sei 2015), and re-imagined material culture (Craft 2012).

In juxtaposing coppers (ancient symbols of wealth) with icons of consumerism such as the Pontiac Firefly (2007) (chariot of the proletariat and Chief of the Odawa), Yahgulanaas plays with the mercurial concept of status.

The last chapter is a synthesis of the artist’s vision, what influenced it, and where Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas finds his inspiration. Never one to remain confined within a genre, the final section simply announces: “Stayed tuned for more of the Yahgulanaas experience!”

In closing out this volume, Yahgulanaas ponders the new frontiers of expression roiling in his imagination. The clues about his direction are evident in paintings such as Valiant (2011), Kyrgyz (2013), and the EMMA Collaboration (Untitled 2014).

The Seriousness Of Play delivers many insights about the life of the artist and his oeuvre. It also serves as an artefact of his culture. As much as the Haida are manifested through Yahgulanaas, he too is a product of their aesthetic traditions. His creative vision may have its roots in his maternal family, but it both highlights and carries the changes wrought by twentieth century popular culture and the post-modernist melange that is globalism.

Unlike their isolated homeland on the north Pacific coast, the Haida were not an island unto themselves. Radio waves filled their airspace in the 1960s and 1970s. Yahgulanaas was the young man who tuned in, turned on, and locked onto those electronic signals. Modernity brought novelty as well as the challenges that shaped his youth and awakened his activism.

Blockades, protests, and a formidable original talent would shake the status quo on Haida Gwaii, as related in Temperate Rain Forest and Culturally Modified Trees (1998). Direct actions contested the rights to ownership claimed by the province, as seen for example in Red White: A Lousy Tale (2004) and In The Gutter (2011), just as Yahgulanaas’s art tested the borders of Haida conventions on customary designs and motifs, such as English Bay (2006) and Hiroshima in Kitsilano (2007) — or pretty much everything in this volume.

For Yahgulanaas, animation, as in cartooning and manga, appeared first in the weekend supplements of newspapers and of course in the comic book literature that filled up his boyhood. He also grew up with television, where he saw the familiar superheroes of pulp fiction in animated form.

In their own ways, comics and cartoons competed for the heart and mind of this young fellow at the same time as he absorbed Haida oral tradition with it own cast of tricksters, heroes, and villains.

His fusing of folklores might involve Raven, Eagle, or Mousewoman marrying into the Spandex clan. Their offspring are the characters Yahgulanaas portrays in his artwork.

Yahgulanaas’s contemporary mythical landscape is accessible through the pictorial storytelling in works such as Red: A Haida Manga (2009), but he never forgets that comics, first and foremost, must be fun. Humour is never lacking in his visual jazz, and his eclectic puns keep viewers busy with many surprises.

I see his work liven the streets and museums of my city, Vancouver. Finding them yields a “Where’s Waldo?” kind of reward. In Abundance Fenced (2011), for example, Yahgulanaas uses 42 metres of industrial steel to capture the organic sweep of salmon swimming upstream against the current of the Fraser River.

I encourage all visitors to Vancouver to seek out this brutal landmark in Kensington Park, at 4900 Knight Street. Like The Seriousness of Play, the payoff will be a glimpse of the future of Haida art.

Nicola Levell has invested much energy in putting together a sumptuous and detailed volume that really does justice to the art and life of Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas.

*

Dr. Eldon Yellowhorn is from the Piikani Nation. He is Chair for the Department of First Nations Studies at Simon Fraser University where he teaches courses dedicated to chronicling the experience of Aboriginal people across Canada. His early career in Archaeology began in southern Alberta where he studied the ancient cultures of plains. He is especially interested in the mythology and folklore of his Piikani ancestors in both ancient and recent times. He is the co-author of First Peoples in Canada (Douglas & McIntyre, 2004), with Alan McMillan. He is currently involved with field research in historical archaeology on the Piikani Nation. He produced a documentary about his work there entitled Digging up the Rez: Piikani Historical Archaeology (2014).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster