#162 The sisters of war

First published August 30, 2017

REVIEW: War Torn Exchanges: The Lives and Letters of Nursing Sisters Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes

Vancouver: UBC Press, 2016.

$32.95 / 9780774832540

*

REVIEW: Sister Soldiers of the Great War: The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps

Vancouver: UBC Press 2016.

$34.95 / 9780774832144

*

Reviews by Margaret Horsfield

Two recent books from UBC Press uncover the vital role of Canadian nurses in arguably one of the most devastating of wars.

Two recent books from UBC Press uncover the vital role of Canadian nurses in arguably one of the most devastating of wars.

In Sister Soldiers of the Great War, Cynthia Toman tells the story of the nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps.

In War Torn Exchanges. Andrea McKenzie presents the letters of two of those nurses, one of whom, Laura Holland (1883-1956), spent her later career in B.C. Holland helped transform child welfare in British Columbia. She took over the Vancouver Children’s Aid Society in 1927 and became B.C.’s Deputy Superintendent of Child Welfare in 1933. Her work, McKenzie notes, “resonated throughout the twentieth century” (p. 213).

“For anyone interested in medical history, women’s history, military history, or in the tangled and terrible perplexities of the Great War,” notes reviewer Margaret Horsfield, “this is compelling reading.”

The centennial years – 2014-2018 – have seen an overdue outpouring of analysis of Canada’s part in this terrible war, its soldiers, stories, regiments, and effect on communities at home. Maybe it was taken this long to get The Great War into perspective and to put a frame around the scale of human damage. – Ed.

*

Determined, disciplined and highly capable, some 2800 Canadian nursing sisters went overseas to serve during the First World War.

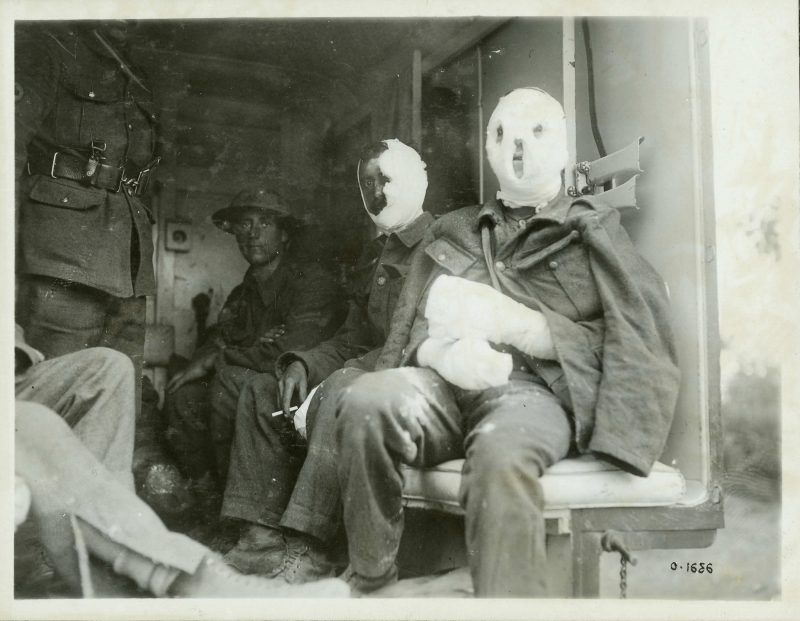

As the lines of battle snaked and spread across Europe and beyond, these nurses — most of whom had never left Canada — experienced unimaginable conditions. They dealt with wounded soldiers from the battlefields of Passchendale, they tended the victims of Gallipoli; many served in hastily assembled field hospitals in Salonika, also on the Greek island of Lemnos; some sisters served in Egypt, some in Malta, others in Russia. They helped assemble massive tent hospitals, some capable of taking 2000 men, in northern France; they nursed in hospitals in French cities and towns. Other Canadian nursing sisters found themselves in large country homes transformed into military hospitals in England, caring for soldiers too badly injured to be patched up elsewhere. The nurses moved where and when they were ordered, never knowing what to expect.

As enlisted members of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, the Canadian nurses became officers, their rank equivalent to that of lieutenant. They had to accustom themselves to military discipline, frequently chafing against the unwieldy bureaucracy. The pressures of their work were intense; they nursed injuries more severe than they had ever witnessed, assisted at operations they had never seen.

Rampant disease often afflicted their patients: dysentery, tuberculosis and malaria, but the men’s mental anguish could be even worse. Just like the soldiers they nursed, the nursing sisters often were frightened and exhausted. All the while, they fought to keep up their spirits, to stay clean, and to vanquish infestations of cooties. They also did their utmost to remain calm. “Many times I’ve stood in the ward … outwardly calm but inwardly thinking, will the next bomb drop on us,” wrote Sister Laura Denton in a letter in 1918. “Then I’ve walked about the camp with only flashes from the guns to show me the Duck boards.”

The two books recently released by UBC Press about these Canadian nursing sisters both provide detailed and sympathetic insights into the work carried out by trained women who waged their own war, from inside their hospitals, on behalf of the soldiers they nursed.

Cynthia Toman’s Sister Soldiers of the Great War is the more wide-ranging of the two, covering the entire duration of the war and attempting a broad overview of these nursing sisters, their place within Canada and within in the military, and the role they played historically, particularly in terms of women’s history.

Andrea McKenzie’s War Torn Exchanges provides exactly what the subtitle indicates, an edited edition, thoughtfully set in historical context, of the letters of two particular nursing sisters: Laura Holland and Mildred Forbes, firm friends and formidable allies.

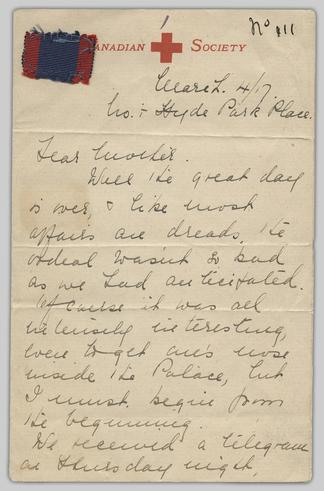

Documents left by the Canadian nurses form the vital core in both books. Each writer highlights, in different ways, the first person voices of the nursing sisters, citing letters, diaries and memoirs. The material the nurses left behind, telling of their war, is all too often fragmentary, brief and incomplete — just a few letters from one nursing sister, part of a diary from another; a scrapbook; a snapshot album. Much of this material is now available in various archives, some having survived by chance, some because families carefully preserved letters and other material. Only a small handful of Canadian nursing sisters attempted to publish anything about their experiences during the war; some of these recalling the experiences much later in life.

Inevitably the nurses’ first-hand accounts reflect the horrors of war: the sounds of the guns, the smell of gangrene, the merciless sacrifice of so many lives. In addition, though, these accounts give extraordinary glimpses into the nature and circumstances of their work, for these women were first and foremost working women, on the job, under great pressure, dealing with military hierarchy and medical challenges the like of which none of them had ever seen.

Cynthia Toman, who has pored over documents left behind by many different nursing sisters, points out rather regretfully that the women did not write in much detail about their work, perhaps because of censorship and professional discretion, or perhaps, as she puts it “It was too difficult to write about mangled bodies and the large number of unpreventable deaths.” Nonetheless, the stark strands of information about their work stand out, they are clear and irrefutable in the documents both Toman and McKenzie cite, providing perspective not honoured often enough in historical accounts: that of women serving in wartime hospitals.

In All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Maria Remarque wrote “a hospital alone shows what war is,” a comment quoted by Cynthia Toman in Sister Soldiers. The hospitals these wartime nurses served in provided unceasing revelations of “what war is.” One night in March 1917, Sister Clare Gass of Nova Scotia handled “Five shot through the chest, one arm blown off. One spine case paralyzed. One fractured pelvis. One pair of trench feet so bad that both feet will have to come off…. ” Sister Helen Petrie wrote, “We three girls had 291 operations in ten nights….” Sister Alice Isaacson tersely noted “Convoy tonight — gassed cases — 300 men burned with a new German gas…,” and in another letter, “1,795 [patients] in hospital! Each night we have one or two deaths and several hemorrhages … our last convoys are so badly wounded! Fractures, jaw cases, brain cases, amputations…”

In larger hospitals, wards were set up for specific injuries: brain, femur, abdominal, jaw, amputation, gas, knees, chests — and nurses developed on-the-job specialties, as circumstances dictated. As for the wards with the “hopeless cases” — “I know you cannot have the faintest idea. Those poor boys, and their poor relatives,” wrote Laura Denton. “A chap just now said, ‘oh sister, it is a cruel war,’ and I fully realize it.”

Cynthia Toman’s Sister Soldiers of the Great War describes the political, military and medical environment in which these Canadian nursing sisters joined the army and went overseas. Her book follows the nurses to the various fronts on which they served, outlining their personal stories and providing detailed historical background, interspersed with the “voices” of the sisters themselves. For anyone interested in medical history, women’s history, military history, or in the tangled and terrible perplexities of the Great War, this is compelling reading.

Toman emphasises the unusual circumstances in which the nurses enlisted; how wartime broke down so many barriers. Years before they could vote in Canadian elections, these mostly young, single women joined the Canadian Army as sister soldiers, as officers, an “all-women’s cadre within the all-men’s world,” as Toman puts it.

Women had never before served as integrated members of the Canadian armed forces, though Canadian nurses had served on earlier battlefields, including the Boer War. Just as men rushed to enlist in the war effort, Canadian nursing sisters eagerly answered the call for to participate in this “war to end all wars.” Only qualified nurses could apply, and they came from all backgrounds: agricultural, working class, and privileged upper class. Most successful applicants had taken their training at nursing schools across Canada; by the outbreak of war in 1914 many hospitals, from Montreal to Winnipeg to Victoria, were offering three-year training courses to aspiring nurses.

Crisply disciplined by stern matrons throughout their training, these nursing sisters, in their starched headgear and white aprons, represented a newly respectable and highly regarded profession for women. In the wake of Florence Nightingale’s legendary efforts during the Crimean War, the profession of nursing changed dramatically in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Once regarded as little more than menial servants working in private care, nurses commanded increasing respect as their education improved, their confidence grew, and their role became established in hospitals.

Like the soldiers caught up in a war no one expected to last, the nursing sisters found themselves in a war longer and infinitely more terrible than they had imagined. As the death toll rose, some questioned what they were doing, and how it could be right to patch men up and send them back to the front as soon as possible, only to face re-injury or death. “After nursing men back to a ‘sort of health,’” wrote Sister Frances Upton, “away they go and get killed — it all seems so useless sometimes.”

Another sister described the crowds of young men — eight thousand passed near her tent hospital in France in one night — heading to the Front “to be wrecked mentally and physically, mutilated, annihilated oh, the tragic horror and pity of it!… In Rouen they passed our tents day and night unceasingly; singing, always singing, in the daytime….” And Sister Laura Holland, at her first posting in a hospital in England in 1915, before even seeing a battlefield, wrote to her mother “Being with the men makes me realize the awfulness of the War. It is pitiful to see how every one of them dread the possibility of … having to go back.”

Because Andrea McKenzie, in War Torn Exchanges, focuses specifically on the letters and experiences of two nursing sisters, her book reveals a great deal about the personalities of her subjects. They speak for themselves: Laura Holland in her expressive and frank letters to her mother, Mildred Forbes in her shorter, more formal, but heartfelt letters to her friend Cairine Reay Wilson. This book also chronicles a remarkable friendship; Laura and Mildred had been friends for a number of years before sailing to Europe in June 1915. They remained inseparable throughout the war, serving in the same hospitals. During their time abroad they often nursed each other; through fevers and other unnamed ailments they were each other’s staunch defenders.

Both women were in their thirties, older and more experienced than many of their fellow wartime nurses. From privileged backgrounds, well-educated, and well-travelled, they had both been to Europe before the war. Mildred entered the Montreal General School of Nursing in 1905, and had been nursing for many years: her administrative skills ensured she became matron of the nurses on board ship and later at a hospital in France. Laura had taught music for eleven years, travelling extensively; she graduated as a nurse in Montreal in 1913, when she was thirty.

A total of 165 letters from these two women have survived, written home from the same battlefields, hospitals, hotels, and ships. Although McKenzie has edited their correspondence, some letters remain pages long. They give a keen sense of the pace of the war, of the daily unknowns and uncertainties for these two sensible and skilled Canadian women; the letters show how periods of intense and terrible activity could be followed by tedium and exhaustion and administrative irritations, never knowing what could arise, and sometimes wishing more than anything for a good shampoo, and a bath.

With the unpredictable urgency of the war eddying all around them, they were living day by day; in an era of very slow communication, they were communicating brilliantly, writing consistently to their people at home in snatched moments, meanwhile soldiering on with extraordinary fortitude. As for their own safety “We all have to take our chance,” wrote Mildred, “and when one sees the splendid men thrown away — one feels why should we value our lives.”

Posted to the island of Lemnos in the autumn of 1915, they helped set up the first of several hospitals there to deal with the disastrous outcome of Gallipoli. Patients began to arrive even before the tents had been erected. Conditions were appalling — and remained appalling, not helped by the weather — intense heat, torrential rains, deep mud everywhere, followed by record freezing temperatures and snow. Severe lack of water and food, minimal medical supplies, and a military administration in total disarray drastically hampered nursing efforts, and worsened the spread of dysentery. The two nurses shared their horror in frank and detailed letters, inspiring a constant supply of boxes from home arriving on the island.

Unsurprisingly, this “cadre of women” from Canada, scattered in wartime hospitals across Europe, has inspired earlier books: Maureen Duffus’s Battlefront Nurses in WW1 (Victoria: Town and Gown Press, 2009); Debbie Marshall’s Give Your Other Vote to the Sister (University of Calgary Press, 2007), to name only two of many. A glance through your local library shelves, or, for more detail, through either Toman’s or McKenzie’s bibliography will illustrate the continuing interest.

Of this cadre of women most — but not all, for some were killed in action — returned from war. Some became our leaders in nursing, hospital management, and social services. Some left nursing and became our grandmothers or great grandmothers. We are in their debt, for their work and for their legacy. In their articulation of war, framed by diligent writers and researchers like Toman and McKenzie, we discover anew, from Canadian nursing sisters in the First World War, just what war is. From such articulation, we have much to learn.

*

Born in Port Alberni, brought up in Terrace, Margaret Horsfield attended Simon Fraser University. Following graduate studies in Birmingham, she lived for fifteen years in England, working for BBC Radio in London as a reporter and producer, and writing for many different publications. She also worked for CBC Radio’s IDEAS. The West Coast of Canada eventually called her home. She now lives in Victoria after many years in Nanaimo. Three of Margaret’s six books explore the history of the West Coast of Vancouver Island. They include the award-winning Cougar Annie’s Garden (1999), Voices from the Sound (2008), and, co-written with Ian Kennedy, Tofino and Clayoquot Sound: A History (2014).

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is a new journal for serious coverage of B.C. literature and other arts. It is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review