#144 One family, one lake, one century

How Deep is the Lake: A Century at Chilliwack Lake

How Deep is the Lake: A Century at Chilliwack Lake

by Shelley O’Callaghan

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2017

$24.95 / 9781987915396

Reviewed by Sabina Trimble

First published June 26, 2017

*

In How Deep is the Lake: A Century at Chilliwack Lake, Shelley O’Callaghan reflects on her family’s 100 years at this mountain lake 45 km. southwest of Chilliwack. O’Callaghan’s family property is not contained within Chilliwack Lake Provincial Park, created in 1973. While O’Callaghan acknowledges the deep Indigenous history of the lake before her family built a cabin there in 1923, reviewer Sabina Trimble wishes she had gone further in acknowledging some recent academic writing by B.C. scholars. Trimble points to the displacement, dispossession, appropriation, exclusion, erasure, renaming, reserve reduction, population decline, and cultural destruction that saw Sxótsaqel of the Ts’elxweyéqw peoples become the settlers’ Chilliwack Lake. — Ed

*

Retired environmental lawyer Shelley O’Callaghan’s How Deep is the Lake: A Century at Chilliwack Lake is a memoir about the author’s “quest” to better understand the history of, and the nature of her family’s relationship with, the beautiful and complexly-storied Chilliwack Lake (named after its first inhabitants, the Ts’elxweyéqw peoples, who know it as Sxótsaqel).

Part personal and family memoir, and part historical account of the lake, this book is highly personalized, at times moving, and generally well-researched. Celebrating a romantic relationship with nature familiar to many Canadian cottage owners, it sheds light on how intimately bound one family’s identity has become to this freshwater lake (“it seems like part of our DNA,” O’Callaghan states), located about 140 kilometres east of Vancouver.

What begins as a research journey to “learn about Chilliwack Lake so that my grandchildren would know the history of this place,” ultimately spurs the author to “question [her] relationship with the environment, Indigenous peoples and the social dynamics of the family” (p. 278).

The author conducted most of her historical research over the course of one summer she spent at the lake and surrounding area, memories of which provide the framework for the bulk of the book. The first and final chapters, describing her family’s activities and rituals on opening and closing day at the cabin during the summer of her research, book-end sixteen short, generally chronological chapters focused on the history of the lake. Throughout, O’Callaghan interweaves these historical accounts with her personal reflections.

She works her way through a list of research questions and recounts discussions with her children and grandchildren about her findings. She also describes the family’s searches for physical remnants of the past on the land. The narrative shifts, sometimes uneasily, between past and present tenses, and between a first-person memoir voice and another third-person omniscient voice to distinguish the author’s memories and reflections and the historical account.

Framed by her personal experiences over the course of the summer of research, the historical narrative begins with a discussion of geological history, responding literally to the titular question: “how deep is the lake?” It is followed by two chapters on the history of Ts’elxweyéqw locals, and several more on the earliest arrivals of non-Indigenous peoples in the area.

One chapter imagines the first visit of the author’s grandfather, Christopher Webb. It describes the family’s construction of the Webbs’ original log cabin in 1923, and their acquisition of 27.5 hectares of land at the north end of the lake, to establish Cupola Estates in 1929. This chapter is followed by two that focus on the experiences and achievements of the author’s grandmother and mother.

The book not only celebrates family accomplishments, but also earnestly sheds light on the less rosy aspects of the family portrait, such as Webb’s disownment of his son Rowland (and the subsequent breakdown of the rest of the family’s relationship with him), because he was gay.

O’Callaghan also traces a fascinating history in which routes of access to the lake (and ultimately, human relationships with it) drastically transformed from an arduous, and at times treacherous, twelve-hour journey on foot and horseback, to a float-plane ride, to a two-hour drive on paved highways from Vancouver.

Several chapters explore the histories of the family’s various neighbours, including a Christian summer camp (established for fatherless boys after the Second World War), an American Fishing Club in the late 1940s, inmates of nearby prison camps in operation until 2002, and friends and family who have lived or stayed in the area over the course of the century.

One of the lovely things about this memoir is the author’s detailed and highly personal descriptions of the lake and surrounding environment. O’Callaghan reflects that she is consistently affected by the beauty of the place, no matter how many times she returns: “I open the sliding doors to the front deck and gaze at the blue-green oval of water nestled in mountains. Its reflection shimmers through my soul. Chilliwack Lake. I am back” (p. 17).

Sitting outside one morning to consider some of her research findings, she describes the stillness with loving detail: “The sun arrives, a morning caress. I gaze across the limpid water, stillness washing over me.” (p. 200). Being near the lake makes her “feel alive” and also inspires her to reflect on her family’s place there. “Our property is a prism through which I am looking at all of my actions,” she states (p. 39).

These reflective moments powerfully express the ways in which our aesthetic and emotional attachments to place, colouring our senses of self and belonging, are inseparable from individual experience and family histories.

Also notable is O’Callaghan’s explicit discussion of her research process — the books she read and archives she visited, the people she spoke to, the historical sites she and her family sought out. She describes in detail her first experiences of handling archival material, as well as the personal contexts for the interviews that informed much of her research.

This is further complemented by personal impressions about her findings. O’Callaghan reflects emotionally on her research, and is frank about having avoided subject matter that makes her feel uncomfortable. When she learns about the history of reserve reductions in British Columbia, she feels stunned, commenting, “we were the wrecking ball destroying Indigenous traditions and culture. We stole their land” (p. 85). “I don’t know what to do with this realization,” she admits, asking herself, “is this a cop-out, that I throw my hands in the air?”

She later acknowledges, “I turn away from other social problems, too… emotionally, I put them at a distance…. How much unpleasant reality am I ready to face?” Such troubled reflections bring to her historical narrative a critical element of self-positioning and emotion that is often lacking in the scholarly literature.

More troubling, however, are the implications of some of the place-making narratives at the heart of this memoir. O’Callaghan acknowledges certain “unpleasant realit[ies]” about her family’s and other settlers’ histories at the lake, but her narrative is also marked by what Renato Rosaldo and other scholars have identified as “imperialist nostalgia.”[i]

Defining the past as a sacred place, memorializing pioneer and settler histories (especially in contrast to cultural and environmental shifts associated with modernism), and characterizing lived places as pristine wildernesses, nostalgic narratives tend to overlook the violence and dispossession that made room for settler histories in B.C. in the first place. They often allow for the elision of other claims and connections to place — particularly those of Indigenous peoples — and make exclusionary colonialist activity appear “innocent and pure.”[ii]

O’Callaghan’s descriptions of the lake frequently focus on what she sees as its remoteness, wildness, pristineness, timelessness. “Where does the magic come from?” she asks herself, “Is it the isolation? The peace and quiet? The pristine beauty? The fact that it never seems to change? What, exactly, is the magnetic pull of this wilderness lake?” (pp. 43-44).

Describing the area prior to the arrival of non-Indigenous settlers, she writes, “In those days, of course, there were no borders, no countries called Canada and the United States. No maps, either. Just endless, stateless, wilderness” (p. 47).

The lake, such descriptions suggest, was an empty wilderness untouched by human beings until the serendipitous arrival of the earliest settlers and pioneers. Such wilderness and pioneer narratives are common in Canadian origin mythology.[iii] They effectively erase from the picture those who lived there before, and who continue to make use of the place to the present day. They veil a history of drastic transformation, displacement, and exclusion that made way for pioneer presences in the first place.

O’Callaghan also ponders why place names in the region have changed. She considers the landmarks named after her family and other pioneers (a lake and a mountain for Charlie Lindemann, another mountain for her grandfather, and a creek for her grandmother, for example) to be testaments to the integrity and depth of their connection and claim to this place (p. 147).

She also acknowledges the inherent power of naming places as a means of claiming them. “Why do we name things?” she asks. It is because “we are putting our stamp on the place. We own it. It’s ours to name” (p. 195). She is not wrong in this. Renaming places has been among the most powerful instruments in the colonization of Indigenous lands in southwestern B.C. and indeed, all across Canada. Naming goes hand-in-hand with exclusivity.

In her research on local Indigenous history, O’Callaghan encountered a map in A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas that identifies the original Ts’elxweyéqw word for Chilliwack Lake as Sxótsaqel (sacred lake),[iv] but she sees this name as a relic of the past. “Sacred is what the Ts’elqweyeqw men, women and children called the lake,” she writes.

In her research on local Indigenous history, O’Callaghan encountered a map in A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas that identifies the original Ts’elxweyéqw word for Chilliwack Lake as Sxótsaqel (sacred lake),[iv] but she sees this name as a relic of the past. “Sacred is what the Ts’elqweyeqw men, women and children called the lake,” she writes.

Although for Ts’elxweyéqw people that name remains in use, another “stamp” has already been put on the lake in public consciousness. It is now called Chilliwack Lake, and “we own it,” as suggested by O’Callaghan’s frequent and uncritical use of first-person possessive pronouns describing the lake.

The book represents Indigenous connections to the lake as part of a mysterious past that O’Callaghan struggles to engage. While she acknowledges that “this land was originally held by others” who “possibly … lived here and would have loved it as much as I do,” she follows this acknowledgement with, “but this land is now ours.” (p. 46).

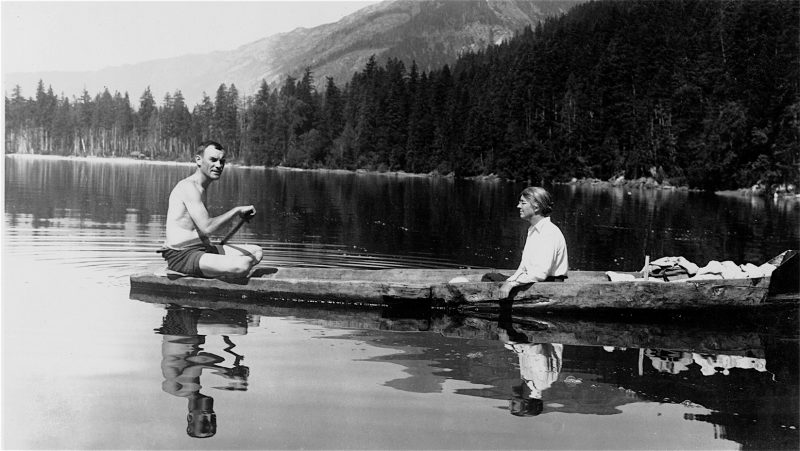

Indigenous people’s connections to the lake are symbolized by artifacts that raise more questions than they answer — Cowichan sweaters that the author knows little about, the family’s dugout canoe, carved by an Indigenous man whom the author never knew and is unable to uncover much about.

O’Callaghan learns from her trips to the Stó:lō Nation Archives in Sardis that Ts’elxweyéqw peoples lived permanently at the lake at one time, but a natural disaster necessitated their southwestward migration to the present-day Chilliwack area.

At that point in her narrative, the lake and its environs transform into a remote, unpopulated wilderness upon which “the family’s pioneers” can now “stumble” (pp. 23, 101). And yet, Ts’elxweyéqw people to this day claim kinship connections to the lake and also maintain material relationships with it, hunting there and gathering cedar bark and cedar root, as well as other medicinal plants. “Did the lake shape them as it has shaped us?” O’Callaghan asks rhetorically at the end of her chapter on First Peoples (p. 51). The answer is yes, of course it did. And that has not changed — it still does.

Certainly, there are elements of this memoir that distinguish it from the kinds of nostalgic literature Renato Rosaldo critiqued in 1989. O’Callaghan does not completely avoid a history of colonialism or Indigenous peoples, and, as noted above, at times she is troubled by her own sense of nostalgia, acknowledging its power as a cover-up for uncomfortable truths.

She is astonished by the tremendous population declines and land loss that B.C. Indigenous communities underwent in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, she reflects on the history of residential schools and speaks to her grandchildren after reading the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (2015) (and decides to volunteer for the TRC in some capacity),[v] and she laments the disproportionate representation of Indigenous peoples in Canadian prisons.

But these discussions tend to focus on more generalized, systemic processes of colonialism in Canada. In so doing, they avoid directly situating the settler activities and stories O’Callaghan celebrates within the highly specific and local history of Indigenous displacement that took place in the Chilliwack Lake area and southwestern British Columbia more broadly. A focus on more general past wrongs can take attention away from the benefits and privilege that many Canadians enjoy as a result of those past wrongs, even if they had no direct part in their occurrence.

In one passionate reflection about the Province’s power to expropriate family lands for parks, the author writes, “what would we do if we lost our land?” (p. 269). As I read her heartfelt commitment to fight for what is now her private property held in fee simple (“It would be my Armageddon,” she vows), I wondered if she recognized that her family would not be the first to lose their land, or that pioneer and settler histories in B.C. were made possible through massive appropriations of Indigenous lands, or that this place of gathering for her family — this “place of traditions and celebrations” — has always been, and continues to be, such a place for many others as well.

*

Sabina Trimble completed her MA in history at the University of Victoria in August 2016, and her BA in history at Mount Royal University in Calgary in April 2014. For her Master’s project, she collaborated with the Xwelmexw community of The’wá:lí (south of Chilliwack) to build an interactive, digital map of the community’s traditional and reserve territories. She published “Storying Swí:lhcha: Place Making and Power at a Stó:lõ Landmark,” an exploration of storytelling about the freshwater lake called Swí:lhcha (commonly known as Cultus Lake) in BC Studies in summer 2016. She is currently enjoying a short hiatus from grad studies, living with her husband Colton outside of Calgary and working in the charitable and philanthropic sector in the city. She will be applying for PhD programs soon, with plans to return to university in Fall 2018.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

[i] Renato Rosaldo, “Imperialist Nostalgia,” Representations 26 (Spring 1989), 107-122. For other important discussions of nostalgia and pioneer commemoration, see Jeff Oliver, “Harnessing the Land: The Place of Pioneering in Early Modern British Columbia,” in An Archaeology of Land Ownership, eds. Maria Relaki and Despina Catapot (London: Routledge, 2013), 170-191; and Paige Raibmon, “Back to the Future? Modern Pioneers, Vanishing Cultures, and Nostalgic Pasts,” BC Studies 135 (Autumn 2002), 187-193.

[ii] Rosaldo, “Imperialist Nostalgia,” 107.

[iii] See Elizabeth Furniss, “Pioneers, Progress, and the Myth of the Frontier: The Landscape of Public History,” BC Studies 115 (1997), 7-44.

[iv] A Stó:lō-Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson (Chilliwack: Stó:lō Heritage Trust, 2001).

[v] The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Volume One. Summary: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling the Future (Toronto: Lorimer, 2015).