#135 The W̱SÁNEĆ revisited

The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours: Diamond Jenness on the Coast Salish of Vancouver Island, 1935

by Diamond Jenness. Edited and with an introduction by Barnett Richling

Oakville, Ontario: Rock’s Mills Press, 2017

$24.95. / 9781772440362

Reviewed by Chris Arnett

Revised June 2020

*

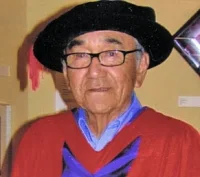

The overlooked ethnographic work of New Zealand-born Diamond Jenness (1886-1969) has been finding its way into print in recent years thanks to Barnett Richling, an anthropologist at the University of Winnipeg.

Richling’s In Twilight and in Dawn: A Biography of Diamond Jenness was published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in 2012, followed by Three Athapaskan Ethnographies: Diamond Jenness on the Sekani, Tsuu T’ina and Wet’suwet’en, 1921-1924 (Rock’s Mills Press, 2015).

Now Richling has turned to Jenness’s unpublished work in 1934 and 1935 among the Saanich people (W̱SÁNEĆ) of southern Vancouver Island and adjacent Gulf Islands, completed for what was then the National Museum in Ottawa.

Reviewer Chris Arnett commends Richling’s welcome efforts while flagging a few books about the W̱SÁNEĆ that might have enriched The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours: Diamond Jenness on the Coast Salish of Vancouver Island, 1935. – Ed.

*

For over seventy years an important unfinished ethnographic manuscript and a stack of typed and handwritten field notes, recording the work of anthropologist Diamond Jenness with knowledgeable Coast Salish elders, languished in obscurity known only to a few specialists.

For over seventy years an important unfinished ethnographic manuscript and a stack of typed and handwritten field notes, recording the work of anthropologist Diamond Jenness with knowledgeable Coast Salish elders, languished in obscurity known only to a few specialists.

Following his field work on the Saanich Peninsula, the east coast of Vancouver Island, and the Fraser Valley in 1934 and 1935, Jenness began writing. He completed nine of his sixteen planned chapters before other interests intervened.

Now, thanks to the work of editor Barnett Richling and Rock’s Mills Press, Jenness’s manuscript, with additional material gleaned from his field notes, is made available to a wider audience in The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours: Diamond Jenness on the Coast Salish of Vancouver Island, 1935.

As Richling writes in his preface, readers will discover “its author’s twin penchants for favouring description over analysis and plain language over jargon,” the result being “an account that deftly straddles the boundary between ethnography and oral history” (p. vii).

The book is divided into two parts. Part 1 reproduces the first nine chapters of Jenness’s original manuscript, “The Saanich Indians of Vancouver Island,” with three final chapters prepared by Richling from the notes Jenness had arranged by subject matter. Richling has not rewritten Jenness, as he explains: “these are basically from his pen as well, my job being less one of writing than of assembling each chapter using unabridged (or lightly edited) passages in these notes” (p. viii).

Part 2 consists of 45 narratives by Coast Salish elders from Saanich, Cowichan, and Katzie communities. Many of these are priceless Origin Stories (sxwi’em), hitherto unknown outside oral traditions.

Jenness was a traditional and perceptive anthropologist. He followed the “cook book” style of his contemporaries (i.e., cultural description using subject headings such as fishing, clothing, childhood, dwellings, guardian spirits, etc), but he was also very interested in the non-material universe of myth and local history.

Descriptions of sinallhki the two headed snake and other powerful beings (st’lequm), spiritual training, guardian spirit encounters, and shamanic healing co-exist with narratives of little-known historical figures such as the nineteenth century Saanich warrior, Kwalahunzit.

These detailed and fascinating accounts will significantly enrich the reader’s knowledge of the Indigenous history and culture of southern Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands.

While a most welcome volume in the field of Coast Salish studies, The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours also represents something of a lost opportunity. There is no attempt to engage with the descendant community, which is not surprising given that the editor, while an anthropologist, is not a Coast Salish specialist. Richling’s purpose was instead to complete the manuscript Jenness left unfinished as a tribute to a man whose “life and career have engaged my scholarly interest since the late 80s” (ix).

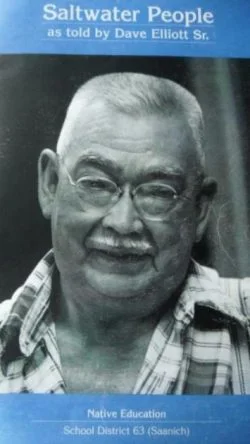

The unfamiliarity with local sources is notable in the lack of reference to standard W̱SÁNEĆ publications such as Dave Elliott’s Salt Water People (School District 63, 1990, edited by Janet Poth), or Earl Claxton Sr. and John Elliott’s The Saanich Year (Saanich School Board, 1993), and their Reef Net Technology of the Salt Water People (Saanich School Board, 1994).

The distant relationship of the editor is also reflected in the absence of local geographical references in the index. Salt Spring Island is mentioned five times in the text but does not appear in the index. Simon Fraser gets a nod but not the Fraser River. Similarly, other landmarks (Point Roberts, Mayne Island, Pender Island, Tsartlip, Koksilah, Sooke, etc) and names — Albert Wesley, Jimmy Fraser, the various guardian spirits, etc. — while mentioned throughout the text, are not indexed. More familiarity or attention with the local cultural and historical context would have enhanced the work.

Those familiar with Jenness’s original 330 pages of notes will recognize the substantial amount of interesting material that was not included in The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours. Much of this information consists of historical and site-specific accounts of stl’eluqum (dangerous fierce, powerful beings) and famous Indigenous leaders such as Tzouhalem that are found nowhere else.

I was excited when I heard that Jenness’s 1934-35 fieldwork was being published, but I am a little disappointed that it was not complete. But this was not the intent of this book. It was to bring to light the invaluable work of a professional who recorded data from knowledgeable people confident in who they were and willing to share what they knew.

*

Chris Arnett is an author, artist, archaeologist, musician, historian, and heritage consultant who lives on Salt Spring Island and in the Vancouver area, where he is currently a sessional instructor in the Department of Anthropology at UBC. His parents, grandparents, and great grandparents instilled in him a keen interest in North American history and in the people and culture of his ancestral homelands of New Zealand, Cornwall, and Norway. He continues his ongoing self-directed and institutional ethnographic, archaeological, and sometimes musical research in British Columbia.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.