#122 River-as-machine vs ecosytem

A River Captured: The Columbia River Treaty and Catastrophic Change

by Eileen Delehanty Pearkes

Victoria: Rocky Mountain Books, 2016

$20 / 9781771601788

Reviewed by John Gellard

First published April 20, 2017

*

Previously, in her Harnessing The Power: Voices from Two Rivers of the Peace and Columbia (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012), Meg Stanley assessed the land and communities inundated or moved to make way for W.A.C Bennett’s “Two Rivers” damming regime of the 1950s and 1960s.

Previously, in her Harnessing The Power: Voices from Two Rivers of the Peace and Columbia (Douglas & McIntyre, 2012), Meg Stanley assessed the land and communities inundated or moved to make way for W.A.C Bennett’s “Two Rivers” damming regime of the 1950s and 1960s.

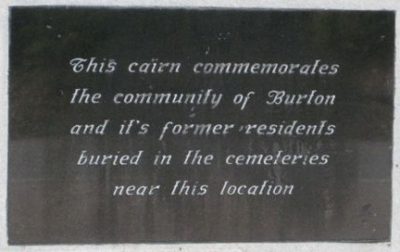

For one dam alone, the High Arrow (Keenleyside) Dam, completed in 1968, BC Hydro appropriated 3,144 properties in Arrow Lakes and relocated 1,350 people.

Communities lost or moved included Halcyon Hotsprings, Arrowhead, Arrow Park, Burton, Fauquier, Needles, Edgewood, and Renata. Now, reviewer John Gellard assesses A River Captured, Eileen Pearkes’s exploration of the controversial history of the Columbia River Treaty of 1964 and its impact on the ecology, farmland, salmon, and politics of the Kootenay region. — Ed.

*

Once upon a time there was a valley, wide and flat, flanked with snow-capped mountains. A huge river slowed down here for 200 km and formed two narrow lakes. There were sandy beaches, sloughs and eddies where waterfowl nested, and rich alluvial soil where you could harvest a crop of hay before the late spring flood, and harvest another crop in the late summer.

A steamer went up and down the lakes collecting fresh cherries, peaches, apples and vegetables from hamlets with names like Renata, Deer Park, Halcyon, Appledale, and Arrowhead. Kokanee salmon and bull trout spawned in the deltas of the small streams cascading from the mountains. You could selectively log your fir, cedar and cottonwood, and on the slopes you could graze cattle.

But that valley is gone. The Arrow Lakes on the Columbia River between Castlegar and Revelstoke are now behind the High Arrow dam under a reservoir storing water to generate megawatts and provide flood control for farms and towns in Washington and Oregon.

A River Captured, by Eileen Delehanty Pearkes tells in fascinating detail the story of the Columbia River Treaty (CRT). We find out why virtually all of the Columbia River and the Kootenay River became a series of reservoirs.

The geographic anomaly of the 49th parallel slices repeatedly through the north-south flowing rivers. This becomes a problem when you need to control the flow of the rivers. Each country strives to maximize its own benefit.

Pearkes shows that there are two fiercely opposed views of how humans should use a river system. The first is to realize that a river is an ecosystem. Human activity can be part of the life of a river. The Sinixt Indians lived with those rivers for millennia, migrating with the hugely abundant salmon, deer and birds, and making use of the bountiful variety of plants that grew in rhythm with the water cycle. Farmers settled in the valleys and took similar advantage of the water cycle.

The other view is that a river should be controlled and turned to its so-called “highest and best” human use. If you get flooded out, you deal with that by flood control — rather than by not building your town in the flood plain. If you need electricity, or if you want to make the desert bloom, you build a dam.

Clearly, the river-as-machine view has prevailed since the Grand Coulée Dam on the Columbia was conceived in the 1930s and completed in 1942. The idea was to make the semi-desert of eastern Washington bloom as farm land. Then the war came along and the dam’s best use was to generate electricity for munitions manufacture.

Ecologically, the Grand Coulée was a disaster. It blocked the ocean going salmon from the upper Columbia in B.C. There was a tentative plan to build a 12 km fish ladder to help the fish over the 168 m structure. It was far too expensive and probably wouldn’t have worked anyway.

Once you start controlling a river, you can’t stop. Flood control and electricity generation could be enhanced by putting more dams upstream.

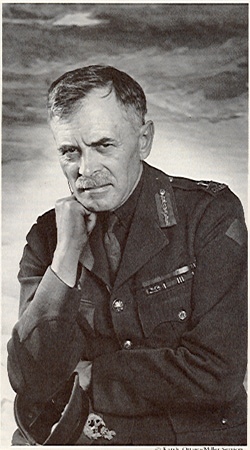

But there was that pesky 49th parallel. Canada’s formidable General A.G.L. McNaughton, avatar of the river-as-machine philosophy, wanted to keep Canadian control of the rivers. He hatched a scheme to divert the upper Kootenay into the Columbia and later to build a tunnel to take Columbia water to the all-Canadian Fraser River.

Mercifully, the byzantine machinations of the CRT in the 1960s put a stop to that. Pearkes gives us the details, but in the end, B.C. got money and downstream benefits in exchange for 15 million acre-feet of water storage behind the High Arrow, Duncan, and Mica dams. We also got flood control from the Libby Dam on the Montana segment of the Kootenay River.

Pearkes toured the entire river system in search of human interest stories. She found tales of heartbreak and enormous courage, and of breathtakingly callous government high-handedness.

Janet Spicer grows organic vegetables on what’s left of her father’s Arrow Lake farm – the 29 acres above the flood line. Her rich topsoil was backhoed up from the valley bottom before the flooding.

Her father, Christopher Spicer, was offered $30,000 for his farm in the late 1960s. He searched the province for a comparable property but could find nothing for less than four times that price. He refused to sell and hired a lawyer. He kept his farm and got $60,000 from Hydro for an easement to flood the best 100 acres, to put the highway across his place, and to build a substation there.

He did not live long after watching the floodwaters cover his land. Janet carries on.

There are many similar stories of Hydro chiseling, threatening, and bullying landowners to give up their land. The boast by W.A.C. Bennett that the province got “tens of millions of dollars” for 7.1 million acre-feet of Arrow Lakes water storage rings hollow.

“No one in government cared about the people who lived here, who loved living here. No one was consulted,” says Janet Spicer.

The reservoir behind the Libby Dam backs up into BC and carries the fatuous name of “Lake Koocanusa.” The land is quite dry with open “montane” vegetation, suitable for free range cattle.

Here, Pearkes meets Stanley Triggs, who photographed and documented the dispossession of prosperous ranchers. “I met the people as I recorded them,” says Triggs, now in his 80s. “I documented a tremendous loss…. They whittled those people down to the bone. What they got paid for their land was criminal.”

What about mitigation? Pearkes holds out hope that the circle of reconciliation between the ecologists and the controllers might be closed. Perhaps, but that’s a long shot.

Heroic attempts at mitigation seem to start with individual initiative. Brian Gadbois begins to solve the severe problem of late winter dust storms from the dried out Arrow reservoir. He gets Hydro to support the annual sowing of ryegrass. This helps until Hydro loses interest.

Dutchy Wageningen devises a method to let bull trout migrate from Kootenay Lake to Duncan Lake through the double discharge gates on the Duncan Dam. There is a scheme to encourage ocean sockeye to migrate up Okanagan Lake, and eventually into the upper Columbia.

Mitigation is all very well, but what have we really learned from the Arrow Lakes disaster and associated calamities? Is history repeating itself after fifty years?

I’m familiar with the Site C Dam controversy, and I’m having déjà vu. There’s that same atavistic drive to “control” the Peace River for no good reason, the same chiseling and bullying of landowners to make them give up, and the same “scorched earth” gambits.

Nevertheless, A River Captured leaves one with hope. It is required reading for anyone interested in the relationship between nature and human beings.

“Can we stop seeing the river [or nature in general] as a villain and increase our resilience and adaptability to its natural rhythms?” asks Eileen Pearkes.

Many British Columbians are weighing the answers to such questions as the B.C. provincial election campaign is now in full swing–and BC Hydro’s massive Site C dam project increasingly becomes a topic of conversation.

[See Brian Wilson, The Arrow Lake Saga,” Kootenay/ Nakusp (November 1, 2014)]: http://www.archivos.ca/?p=23

*

John Gellard spent his childhood in England and Trinidad, donated his adolescence to an English boarding school, earned an MA in Philosophy from the University of Western Ontario, and taught English and Drama in London, Ontario, for seven years. In 1973, he arrived in the West Kootenay where he felled and peeled pine logs on his “wild land” property and built a log cabin. Gravitating to the city, he taught drama for thirty years at Vancouver Technical Secondary School and Kitsilano Secondary. He still helps run writing workshops for students, notably (since 1993) an annual overnight retreat on Gambier Island. His articles have appeared in the Globe and Mail and the Watershed Sentinel. He takes an active interest in environmental issues and travels extensively in B.C. He lives among friends in Kitsilano and on Hornby Island, has two grown sons, and retired from teaching English and Writing at Kitsilano Secondary School after being named Canada’s “Best High School Teacher” in a Maclean’s poll in August 2005.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Comments are closed.