#104 Literary greenhorn dads

The Dad Dialogues: A Correspondence on Fatherhood (and the Universe)

by George Bowering and Charles Demers

Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016

$17.95 / 9781551526621

Reviewed by Christian Fink-Jensen

First published March 15, 2017

*

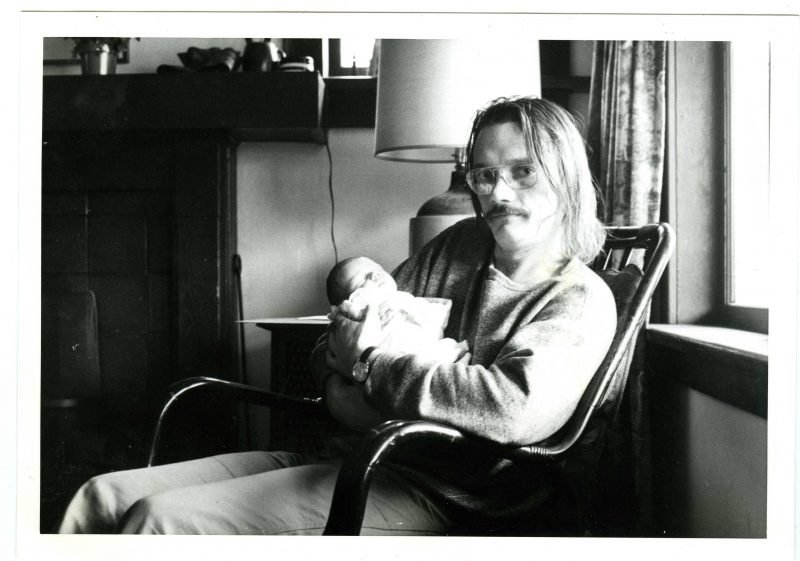

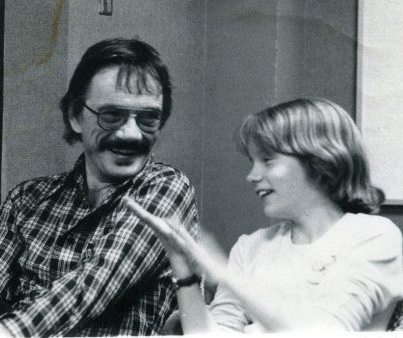

Vancouver writers George Bowering, born in 1935, and Charles Demers, born in 1980, had daughters – Thea and Josephine – more than forty years apart.

Vancouver writers George Bowering, born in 1935, and Charles Demers, born in 1980, had daughters – Thea and Josephine – more than forty years apart.

The Dad Dialogues contains Bowering and Demers’ monthly correspondence over 18 months, including their impressions as expectant and greenhorn fathers, their supportive relationship with their partners Angela and Cara, and the fears, expectations, and commonalities of fatherhood in 1971 and 2015 — two very different eras when their daughters were born.

Reviewer Chris Fink-Jensen, himself the father of two young children, finds much of value. “As individuals,” he reflects, “we have a terrifying capacity for narrow self-interest but, as The Dad Dialogues shows, parenthood can widen the scope of our compassion. – Ed.

*

I must confess that when I was asked to review a book featuring a poet and a comedian talking about fatherhood, I was a little reluctant. Here we go, I thought, yet another title featuring emotionally inept new fathers bumbling through pre-natal classes, passing out during birth, and then attempting to solve every parenting challenge with bungee cord, duct tape, and jumper cables.

Thankfully, The Dad Dialogues by George Bowering and Charles Demers goes beyond these stereotypes. Conceived as an epistolary exchange between men of different generations, the aim was to compare notes on fatherhood. What was different, what was the same? Did fathers of the early 1970s have the same excitement and/or dread as the new dads of today?

The book begins with George, an octogenarian writer (and Canada’s first poet laureate), recalling his version of how the project was conceived — viz., during a “lull” in a baseball game. He and Charles were discussing Charles’s forthcoming fatherhood. George related several stories about his own experience of becoming a father back in 1971.

It was then that Charles (or George’s wife, Jean, depending on whose version of events you believe) suggested that the two of them write a book about parenthood. Charles, a thirty-something author and comedian, was smitten with the idea, imagining it as a gift for his soon-to-be-born daughter.

The book would be, he writes, “A record of the first parts of her life, a book co-written in her honour by one of Canada’s most celebrated, beloved, and talented men of letters. And George Bowering!”

With their purpose defined, the duo begin a monthly exchange of letters. From the beginning it’s clear that their experiences of impending-fatherhood do not align with popular notions of how things should be. “People want to see a big fat pregnant lady and a terrified father-to-be,” Charles writes. “It’s part of the spectacle of anticipating the baby. But as a couple, we’ve let them down….”

For his part, George recalled that he was also fairly calm regarding the birth itself and credits that to the Lamaze classes he and his partner had taken. “You have to remember that 1971 occurred in the late sixties, when you were supposed to be hip about everything.”

But while neither George nor Charles found the physiological aspects of birth overly nerve-wracking, both admit to finding other parts stressful, including meeting the expectations of others. Deriding what he calls “yuppie performances,” Charles laments how several of his friends seem to be in a race to have the most “idiosyncratic birth possible (you haven’t really had a baby till you’ve delivered into a hand-crafted, artisanal kiddie pool in a purpose-built cottage in the forest with a roof thatched by a team of Cuban doulas).”

As it turns out, neither man has much patience for anyone who questions corporate medicine, especially those interested in non-mainstream birth experiences. Their dismissive attitudes, however, are (almost) always offered with a generous leavening of humour.

As the book progresses, George and Charles move on from the social aspects of fatherhood and into its personal and psychological impacts. Despite initially claiming to be “calm,” both men gradually reveal themselves to be consummate worriers, partly by nature but also thanks to their roles as fathers. It’s an endearing revelation because it’s so very human.

As individuals, we have a terrifying capacity for narrow self-interest but, as The Dad Dialogues shows, parenthood can widen the scope of our compassion. The world’s tragedies, often dismissed as happening elsewhere and to slightly unreal people, become vividly affecting — either because we see how events might impact our children or because we can empathize with the love other parents feel for their kids.

In one particularly moving passage, Charles describes his reaction to reading about a Palestinian child, roughly his daughter’s age, who had been killed. He feels for the child’s parents who “should have been thrilling to roughly the same milestones as Cara and me for the next few decades.” Instead, their baby is already gone. “I don’t usually cry when I read the news,” Charles continues, “but I bawled when I read that.”

It’s in these passages, where George and Charles reflect on their hopes and fears, that the book offers the most. For any new parent-to-be there are plenty of hopes but, as the authors often humorously illustrate, even more fears. This doesn’t make the book depressing. Rather, it gives other parents permission to worry about the future of their children and provides reasons for all of us — parents or not — to work for a better world. Even forty plus years into fatherhood, George still frets about the world he has brought his daughter into, lamenting that most people are “more concerned with their utility bills than world events.”

Where The Dad Dialogues comes up a little short is in highlighting the differences between fatherhood in the 1970s and the 2010s. Other than bragging about the wonders of ultrasound, George and Charles don’t spend much time considering how fathers’ roles have changed. This seems like a missed opportunity. Now that the “average” father is no longer merely a patriarch and disciplinarian, what does this new, more nurturing role mean for men, their families, and the world at large? In other words, what value does an involved father provide? It’s an important question.

Several studies (including a decades long British study published in the journal Evolution and Human Behaviour) have found that children whose fathers were closely involved in their lives had dramatically better social, behavioural and psychological outcomes. Specifically, kids with involved dads became adults with higher IQs and were more socially mobile than those whose fathers were less involved.

It would have been interesting to hear Charles and George’s reflections on their own purpose as fathers, especially with regard to changing social roles and expectations. If nothing else, I’m sure it would provide rich comedic material involving pipes, slippers, and newspapers.

It would have been interesting to hear Charles and George’s reflections on their own purpose as fathers, especially with regard to changing social roles and expectations. If nothing else, I’m sure it would provide rich comedic material involving pipes, slippers, and newspapers.

The book is also a touch heavy on biographical detail. This reader would have preferred less about who visited when or which festival so-and-so was speaking at, and more free-form musing.

That said, the less interesting bits are compensated by several moving observations and some hilarious anecdotes (as when Charles brings his infant daughter on stage during a performance: “This is Josephine. She’s named after Stalin.”)

Minor criticisms aside, The Dad Dialogues is an engagingly written look at fatherhood. Despite an almost fifty year age difference, Charles and George align on most aspects of what it’s like to be a father, how marriage gets affected, and what babies are really like.

According to George, the popular encouragement that “babies are tough” is false.

“Bulldogs are tough. Cuban infantrymen are tough. My mother’s roast beef was tough.

“Babies are more like fathers’ hearts – sweet and tender and loud.”

*

Christian Fink-Jensen is a writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. His work has appeared in more than fifty newspapers, magazines, and journals around the world. He is the author and co-researcher of Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer (Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2016). Christian lives in Victoria, B.C.

Christian Fink-Jensen is a writer of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry. His work has appeared in more than fifty newspapers, magazines, and journals around the world. He is the author and co-researcher of Aloha Wanderwell: The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the World’s Youngest Explorer (Fredericton: Goose Lane Editions, 2016). Christian lives in Victoria, B.C.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review

Help Luhombero