#96 Métis longing and belonging

Belonging Métis

by Catherine Richardson (Kinewesquao)

Vernon: J. Charlton Publishing, 2016

$30.00 / 9781926476070

Reviewed by Émilie Pigeon

First published Feb. 28, 2017

*

Despite being recognized as one of the three Aboriginal peoples of Canada in the Constitution Act of 1982, the Métis remain hard to define. From Vancouver Island to Labrador their Métisness can be dormant and barely visible — or sharply defined and fully alive.

In Belonging Métis, Catherine Richardson, also known by her Cree name Kinewesquao, explores questions of Métis identity, longing, and belonging in modern Canada.

Reviewer Émilie Pigeon regards Belonging Métis as a useful road-map for Métis people interested in finding common threads that run through their voices, stories, and experiences. – Ed.

*

Stories flow through people, time and space. Stories are purposeful. Stories are tangible connections to the past and to the present. Stories can encourage, inform, and they can heal. Stories can prescribe ways of being. Stories are tied to identity.

In Belonging Métis, Dr. Catherine Richardson (Kinewesquao), builds on decades of work in the social services profession to investigate the connections between the Métis self and Métis stories. In so doing, she presents a quick and accessible introduction to what “being Métis” means today.

Richardson writes from the perspective of an insider-outsider, in other words, she self-identifies both as a Métis woman and as an academic. Belonging Métis intertwines shared stories and knowledge with decolonial ideas and methodologies informing and educating average readers and social science researchers alike.

The Canadian government, its courts, and its settlers have long struggled with their depictions of Métis people. In this book, the Métis define themselves in the here and now.

Translating academic work into a narrative that resonates with most folks is not easy. Belonging Métis lives up to the challenge and provides a timely contribution to the rich and diverse field of Métis Studies.

Weaving together a selection of voices of Métis people from across Canada who now call British Columbia home, Richardson builds a coherent narrative by analysing diverse meanings and understandings of identity. In doing so, she highlights the importance of Métis stories to Métis wellbeing.

Richardson interviewed willing research participants for her doctoral work at the School of Child and Youth Care at the University of Victoria. The audience for Richardson’s book is primarily Métis people interested in questions of sovereignty, health, wellbeing, identity, and history, and how all of these topics are closely related.

Non-Métis readers will find a thorough introduction to being and belonging to the Métis nation, an Indigenous postcolonial people, and important discussions about the legacies of settler Canada’s colonial past and present.

Stories are sometimes hidden because of underlying power structures that shape habits and behaviours. Métis interviewees occasionally told Richardson they had no Métis stories to share. How could this be?

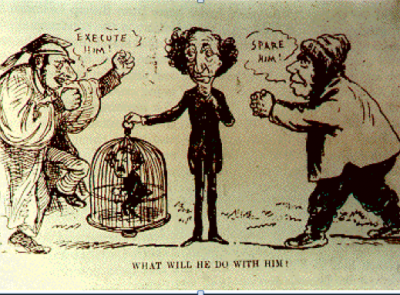

In 2017, the government of Canada repackaged Louis Riel as a Canadian statesman. For the purpose of #Canada150 celebrations, Louis Riel was reborn as the Father of Manitoba and defender of Métis rights.

Meanwhile, the RCMP heritage centre in Regina continues to exhibit objects used to detain and kill the Métis leader. Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, toasted the event by saying, “[Riel] shall hang, though every dog in Québec bark in his favour.”

Celebrating Riel for his actions while cheering the RCMP for Riel’s death and their role in the so-called pacification of the West is hard to swallow. Yet this is the ahistorical tale taught in schools today.

The ongoing legacies of downplaying (or denying) Canada’s colonial past are profound for Métis people. Remembering and repackaging history in a way that minimizes or downplays Canadians’ broken treaty promises, while celebrating the state-sanctioned murder of a Métis leader, exemplifies how the past causes harm in the present.

The legacy of Canada’s colonial past has complex and multifaceted consequences on Indigenous peoples’ health today. Richardson argues that one cannot understand the Métis self without becoming familiar with Canada’s historical legacy, and that Canadians from all walks of life have a responsibility to understand this fact.

Métis men, women, and children developed numerous resistance strategies for surviving and thriving despite the will of the nation state. Richardson explores resistance strategies embedded in the language of Métis interviewees. By providing Métis peoples with a place to share their stories with one another, the medicinal qualities of stories and their beneficial effects come to light.

Richardson notes that the Métis exist between two worlds: the settler world, that is, the Euro-Canadian, Anglo-centric nation state and its structures; and the Indigenous world, with its distinctive governances and diverse cultures. Within the latter, Richardson identifies a third world, a Métis space, in which Métis peoples “experience respite from this separation [from the land and Métis culture] and proceed towards the creation of a self that is more complete” (p. 65.) The exploration of this third space — the Métis space — for storytelling and sharing, and its relation to other worlds, will resonate with all kinds of readers.

Belonging Métis articulates the strong link between contemporary philosophies of self, wellbeing, and the historical contexts that ground them. Métis stories about the past create avenues for understanding today’s world. Stories on Lent and the consequences of misbehaving in the lead-up to Easter hold insights regarding interactions between Métis people and church officials.

Similarly grounded in historical fact, accounts and analyses of the legacies of Métis scrip provides a framework to understanding the relationship between the Métis and the Canadian state in 2017. Richardson’s work emphasizes the importance of Métis-centric and Métis-centred knowledge and experiences for and by Métis peoples.

In this sense, Métis organizations offer an essential health service and Canadian society ought to value them as such. As Richardson remarks, culture doesn’t happen when one is alone.

Providing a Métis space for sharing Métis stories confirms the interwoven nature of the past and present, and how Canada’s ongoing complicated relationship with colonialism impacts the Métis self.

Richardson’s roadmap of ideas offers avenues on how to move beyond decolonization and reconciliation as metaphor, and how to engage with these concepts in practice.

*

Émilie Pigeon is French Canadian settler from the Ottawa Valley (Ontario), former high-school dropout, and doctoral candidate in history at York University in Toronto. Her soon-to-be-defended dissertation on the lived Catholicism of Métis bison hunters involved many summers on the American side of the northern plains digging up Michif-French archival sources and returning them to Métis families. This task is ongoing. She presently works as a digital historian/researcher for Indigenous communities in Canada and the United States.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review