#88 The ’54 Games began modern B.C.

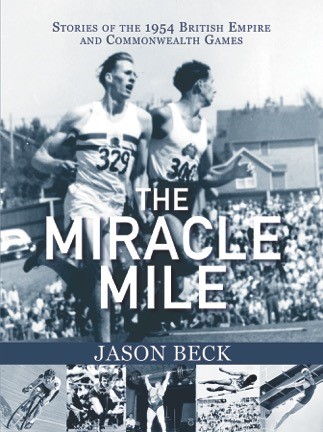

The Miracle Mile: Stories of the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games

by Jason Beck

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2016

$29.95 / 9781987915006

Reviewed by Roger Robinson

First published Feb. 15, 2017

*

In The Miracle Mile, Jason Beck explores the planning, hitches, and setbacks involved in Vancouver’s hosting of the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games.

He dusts off the specifics of the city’s bid and the human stories of the remarkable athletes who made the ten days — July 30 to August 7, 1954 — a watershed in B.C. and Canadian sports history.

Reviewer Roger Robinson insists that the 1954 Games helped transform Vancouver from a colonial outpost to a multicultural metropolis.

After reading The Miracle Mile, he says, “you will never think again that sports stars are all brainless and boring.”

*

From July 30 to August 7, 1954, a little Canadian city tucked away on the very edge of the western world hosted a previously minor sporting festival quaintly called the “British Empire and Commonwealth Games.”

Vancouver? Few people outside BC had heard of it. The wider world, still sweeping up the debris of World War Two, knew of nothing that ever happened in Vancouver. “Empire Games?” (“and Commonwealth” in smaller type?) The previous version happened in drab 1950 New Zealand, and nobody noticed.

Yet things happened in those Vancouver Games in 1954 that resonate sixty-three years later with near-mythic force, things that moved international sport to a new level, and redefined Vancouver’s community and capability. It’s not too much to claim that those nine days brought a major move forward in the process by which former British colonial cities like Vancouver have transformed themselves into vibrant multicultural centres of global significance.

No one quite understood at the time what was happening, because nothing like it had ever happened before. Even now, history still drags its academic feet in recognising the social and cultural importance of sport. There are no good book-length studies of the wider significance of any such Games, except the special case of the Nazi Olympics at Berlin in 1936. So it’s a treat to read a truly fine book that puts fully on record how important those Games were in the history of Vancouver as well as the history of sport.

Author Jason Beck is curator of the BC Sports Hall of Fame in BC Place Stadium, Vancouver, and convenor two years ago of an excellent exhibition about the 1954 Games. In his first book, he proves to be a meticulous researcher, a compelling story-teller, and a crafty realist who knows how to hook his readers. Watch how, two pages into the book, he uses filmic technique to evoke the arriving athletes’ youthful buzz and give period colouring and costuming, but then smartly moves his camera in to introduce his stars:

As the buses loaded with athletes wheezed to a stop outside Empire Stadium, the young men and women who would be the subjects of so many remarkable stories over the next nine days stepped down and quickly became part of the whirling mob of crisp new national blazers and youthful energy. Most of their exploits, however, would be overshadowed by the deeds of just three men among them….

And so into the first close-ups on Roger Bannister, John Landy, and Jim Peters. It’s a skilled teaser.

Beck had no choice but to call his book The Miracle Mile, and put the familiar, iconic Bannister/Landy image on the cover. He accepts, explains, and enhances the mythic power of that moment in the men’s 1-Mile race (Landy’s glimpse over his left shoulder as Bannister’s huge stride powers by on his right, first time ever two men were faster than four minutes).

Beck had no choice but to call his book The Miracle Mile, and put the familiar, iconic Bannister/Landy image on the cover. He accepts, explains, and enhances the mythic power of that moment in the men’s 1-Mile race (Landy’s glimpse over his left shoulder as Bannister’s huge stride powers by on his right, first time ever two men were faster than four minutes).

Beck weaves Bannister/Landy/Peters preliminaries and previews through four years and then nine days of multifarious other stories that have no iconic image or undying legend but make fascinating reading and important history. He shapes it all to lead to that unmatchable last act, the climactic final hour of heroism and horror, when Bannister triumphed gloriously, Landy lost admirably, and poor heat-exhausted Peters staggered, collapsed, nearly died, and appalled the world with memories we wish we could forget.

On his careful way to those final scenes, Beck informs and entertains us with characters and stories we (in my case) never or barely knew. To open, we get the loud and bullheaded Erwin Swangard, the sports editor who first conceived, announced, and shoved into existence the whole idea of the bidding for the Games.

“Screw Hamilton. Let’s get them for Vancouver,” he reportedly said.

Then we meet the irrepressibly inventive Jack Diamond, the meat-packing entrepreneur who thought up fund-raising ideas, from cattle sales to celebrity dinners with Bob Hope, from pre-season hockey games to a bowling-alleys-for-the-Games Sunday that nearly got him arrested for breaking the Lord’s Day Act.

We follow the baby-faced workaholic general chairman of the Games, Stanley Smith, as he somehow steers the whole turbulent process of preparation. The stadium construction is a teetering tale of delays, design errors, and sheer screw-ups. There is near civil war over the location of the venues for swimming and rowing.

Once the first gun goes, Beck is far from content merely to tell us who won what. He shows us that these are real people, not faceless sportsniks. He lets us glimpse the charmingly dashing Trinidad sprinter Mike Agostini as in between winning races he cuts a Casanova swathe through the women of the Games village.

He provides a deservedly full portrait of Jackie MacDonald, who combined Marilyn Monroe blonde beauty with the power and dedication of one of the first women ever to lift weights in training, who gave Canada a silver medal in the shot put but was dumped from the discus by Canadian officials for supposedly infringing amateur rules — in effect, for looking too sexy. We learn a lot about the ethos of the 1950s from these stories.

Through Beck’s careful research, we follow whole lives, not only the few seconds of competition. Tiny feisty Marjorie Jackson-Nelson goes from poverty in outback Australia to four gold medals in Vancouver, happy marriage, work in charities and sports administration, and eventually six years as governor of South Australia.

Doug Hepburn, born in Vancouver with a clubbed foot and alcoholic father, somehow emerges to pioneer new techniques of weight-lifting training and become the strongest man in the world, win Vancouver’s only individual gold medal, fail as a fitness gym businessman, lapse into alcoholism, recover, write poetry, become a philosopher influenced by Eastern spirituality, invent fitness equipment, and keep lifting to break age-group world records.

After reading this book, you will never think again that sports stars are all brainless and boring.

Beck also adds much that is new and much that is enthralling to the most familiar parts of the story. Having written articles on the Bannister and Peters races, I am envious and admiring of how much he manages to add to previous knowledge, and how vividly he recounts what he has discovered.

His Chapter 10, “Saturday August 7, 1954” is as good as historical sports writing gets. His almost mile-by-mile and man-by-man account of the heat and horror of the marathon will be essential reading for anyone in future who wants to know fully what happened to Peters (or Stan Cox, the second English runner, who ended unconscious in a ditch) or what that terrible day meant for marathon running as it has developed since.

Most important, this is a book that shows the Games as a seminal event in the history of Vancouver. Beck convincingly argues that the community (despite all the pre-Games intrigues and squabbles) came together in volunteer unity and found a new confident communal energy. He documents how a city where few residents had ever before seen a black African or Fijian opened their homes to all athletes, and fostered a Games-long atmosphere of genuine international goodwill — “perhaps one of the earliest signs of Vancouver’s future of pervading multiculturalism,” comments Beck judiciously.

From a backward-looking British colonial outpost on the outer margin of Canada, he suggests, Vancouver began to identify itself as an independent entity. If nothing else, thanks to Bannister, Landy, Peters and many others, that week proved that little Vancouver could put on an event that for efficiency, drama, and newsworthiness was truly world class.

[Most photos are from the book, courtesy BC Sports Hall of Fame]

*

Roger Robinson lives in New Zealand and New York. His books include Running in Literature, Spirit of the Marathon, and the Oxford Companion to New Zealand Literature.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook

BC BookAwards

The Literary Map of B.C.

The Ormsby Review