#75 Nechako before the flood

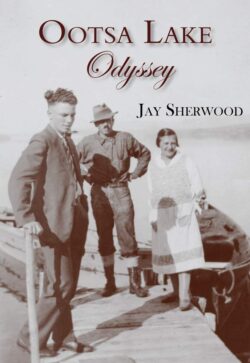

Ootsa Lake Odyssey: George and Else Seel — A Pioneer Life on the Headwaters of the Nechako Watershed

by Jay Sherwood

Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin Press, 2016

$24.95 / 9781987915211

Reviewed by Sage Birchwater

First published Jan. 18, 2017

*

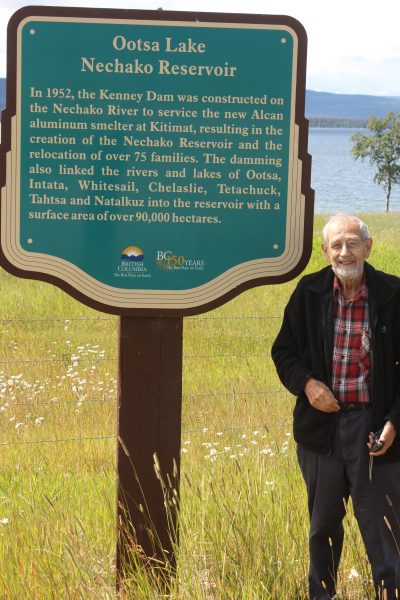

Ootsa Lake Odyssey follows the lives of George and Else Seel, who worked in the Nechako watershed for decades until they were flooded out by the massive 90,000-hectare Nechako Reservoir.

Else was thirty-three years old when she responded to a magazine advertisement by George Seel, a German-Canadian trapper, prospector, and stonemason who had moved into the Upper Nechako country in 1914 — Ed.

*

Around the beginning of the 1900s, settlers established four agrarian communities along the south-facing north shore of Ootsa Lake. Marilla was at the eastern end of the lake close to the portage trail to Cheslatta Lake; Ootsa Lake was the main community at the south end of the road from Burns Lake; Streatham was a small community twenty kilometres west of Ootsa Lake; and Wistaria was ten kilometres beyond there and about fifteen kilometres from the western end of the lake.

Around the beginning of the 1900s, settlers established four agrarian communities along the south-facing north shore of Ootsa Lake. Marilla was at the eastern end of the lake close to the portage trail to Cheslatta Lake; Ootsa Lake was the main community at the south end of the road from Burns Lake; Streatham was a small community twenty kilometres west of Ootsa Lake; and Wistaria was ten kilometres beyond there and about fifteen kilometres from the western end of the lake.

The settlers coexisted with the Cheslatta Dakelh and Wet’suwet’en families who occupied homesteads and remote hunting and trapping areas until the region was flooded in 1952 by the Nechako Reservoir.

George had come to North America from Bavaria in 1911, then disappeared into the backcountry west of Ootsa Lake with two Swedish prospectors to avoid being sent to an internment camp when Canada entered the First World War.

By the fall of 1926, George felt his mining claims might sustain him, so he placed an ad in German newspapers seeking a woman who might want to come to Canada and live at Ootsa Lake and be his wife.

Else Lübcke responded. She was working in the archives of a Berlin bank clipping newspaper articles when she came across George’s advertisement. Part of Berlin’s vibrant cultural life, Else actively was participating in the literary community as a writer with stories and poetry published since 1921. She was hoping to expand her experience beyond the bland humdrum of the nine-to-five routine.

George was thirty-nine years old when he met Else at a hotel near the Vancouver train station. Sherwood eavesdrops on Else’s diary entries to give the reader a front row seat at Else and George’s wedding the next day.

Her intimate writings convey her feelings and first impressions as they sailed up the mainland coast to Prince Rupert, took the train to Burns Lake, and finally arrived in isolated Wistaria.

Else’s articulate diaries allow the reader to empathize with the life of a new immigrant entering Canada and getting established in the rugged British Columbia backcountry.

The reader is immersed in the dreams, aspirations, sentimentalities, and frustrations of the new settler entering a way of life that had been difficult for her to imagine.

Sherwood presents the first years of Else and George’s life together in great detail. After nine months of marriage, Else noted in her diary that she had spent seven of those months alone because George was away trapping and prospecting so much.

“Sometimes I don’t see anybody for days. And still I am very happy and not so alone; always in the best company.”

Sherwood titles the chapter of their life together at the end of the Roaring Twenties as “Prosperity.” Else generated a small income by writing for German magazines about her rustic life in Canada, George’s mining efforts bore fruit, and their son (and future prospector) Rupert Seel was born in December 1928.

As with most people, the decade of the Great Depression was difficult for Else and George. In the chapter “Subsistence,” Sherwood describes the mental and physical hardships experienced by the Seel family as they lived hand-to-mouth and, more often than not, indebted to the local storeowner.

When Canada entered the Second World War, Else was cut off from family members in Germany, now an enemy territory convulsed by the rise of Hitler. She managed to find out news about her family, including her mother’s death, through a friend in New York before the United States entered the war.

Sherwood’s previous and invaluable four volumes documenting the life and photographic accomplishments of Frank Swannell, the noted BC Land Surveyor, lay the foundations for Ootsa Lake Odyssey.

In 1920, Swannell began surveying the headwaters of the Nechako watershed and hired George Seel on his trail-building crew for $3.50 per day. Sherwood includes several Swannell images in Ootsa Lake Odyssey.

Sherwood also digs up a July 29, 1930 Winnipeg Tribune article foreshadowing the proposed flooding of the upper Nechako. Two potential hydroelectric projects were identified for British Columbia. One scheme would have seen water diverted from Chilko Lake into the Homathko watershed, with several dams flooding the Tatlayoko and West Branch valleys. The other project involved the damming of the Nechako River to create a giant reservoir, with water being sent westward through a tunnel to Kemano on Gardner Channel.

The Kenny Dam was finally constructed on the Nechako Canyon in 1952, but George Seel never lived to see it. In the two decades before his death in 1950, he had found employment on various aspects of the project.

The rising water of Ootsa Lake flooded out the four communities of Wistaria, Streatham, Marilla, and Ootsa Lake, and settlers were left to negotiate the best compensation package they could with Alcan (Aluminum Company of Canada) for their expropriated property. Eighty households were displaced, but residents who lived on the benchland above the lake received no compensation even though their communities were gutted.

The Alcan project, signed before W.A.C. Bennett became premier, was the first large-scale hydroelectric project of the post-World War II era.

First Nations citizens living along Cheslatta Lake were only given two weeks to vacate their homes, fields, and traplines flooded by the project and were given minimal compensation by the federal government.

Ootsa Lake Odyssey is a welcome story for readers interested in the history of settlement and working lives in the Nechako watershed, in German immigration to BC, and in the destruction caused by post-war hydroelectric construction in W.A.C. Bennett era.

Through the lives of Else and George Seel, Jay Sherwood documents half a century of life and work at Ootsa Lake and on the upper Nechako drainage before the flooding that changed everything.

*

As a long-time resident of the Cariboo-Chilcotin, Sage Birchwater has written several books about the area including Chiwid (New Star, 1995). Born in Victoria in 1948, Birchwater was involved with Cool Aid in Victoria, travelled throughout North America, and worked as a trapper, photographer, environmental educator, and oral history researcher. Sage served as the Chilcotin rural correspondent for two local papers for 24 years while raising his family south of Tatla Lake. He has also lived in Tatlayoko, where he was a freelance writer and editor, and Williams Lake, where he was a staff writer for the Williams Lake Tribune until his retirement in 2009. His other books include Williams Lake: Gateway to the Cariboo Chilcotin (2004, with Stan Navratil); Gumption & Grit: Extraordinary Women of the Cariboo Chilcotin (Caitlin, 2009); Double or Nothing: The Flying Fur Buyer of Anahim Lake (Caitlin, 2010); The Legendary Betty Frank (Caitlin, 2011); Flyover: British Columbia’s Cariboo Chilcotin Coast (2012, with Chris Harris); Corky Williams: Cowboy Poet of the Cariboo Chilcotin (Caitlin, 2013); and Chilcotin Chronicles (Caitlin, 2017), reviewed here by Lorraine Weir.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

Comments are closed.