#68 Won Alexander Cumyow

ESSAY: Canadian First: The Life of Won Alexander Cumyow (1861-1955)

by Janet Mary Nicol

First published Dec. 28, 2016

*

Canada’s west coast accommodated “two solitudes”—people of the dominant English-speaking community and those of Asian heritage. One man who tried to bridge these separate, often hostile worlds was Vancouver pioneer, Won Alexander Cumyow. He was the first Chinese born in Canada in 1861, and despite limitations imposed on people of Asian background, found opportunities as a successful merchant, police court interpreter, legal advisor and advocate. Cumyow was a father when the vote was taken away from Chinese-Canadians and a grandfather when the vote was given back. His life-time efforts at reconciliation between “east and west” tell a larger story.

Canada’s west coast accommodated “two solitudes”—people of the dominant English-speaking community and those of Asian heritage. One man who tried to bridge these separate, often hostile worlds was Vancouver pioneer, Won Alexander Cumyow. He was the first Chinese born in Canada in 1861, and despite limitations imposed on people of Asian background, found opportunities as a successful merchant, police court interpreter, legal advisor and advocate. Cumyow was a father when the vote was taken away from Chinese-Canadians and a grandfather when the vote was given back. His life-time efforts at reconciliation between “east and west” tell a larger story.

Roots in the gold rush

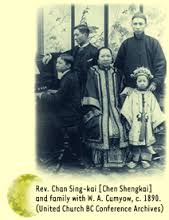

San Francisco once claimed the largest Chinatown in North America. Cumyow’s father, Won Ling Cumyow emigrated from the Canton region of China to the west coast city in 1858. While in the United States, his elders arranged his marriage. Seeking more opportunities in 1860, Cumyow and his bride travelled north to the colony of British Columbia, following news of the Fraser River gold rush. They settled in Port Douglas on the Cariboo trail and ran a store selling clothing and equipment to prospectors. Won Alexander, also known as Wen Jinyou, was born in the BC town on March 26, 1861. He was followed by four more sons and two daughters.

The young Won Alexander spoke Cantonese at home. When he was old enough to help his parents in their store, he learned English as well as Chinook, a language developed between First Nations traders and immigrant settlers.

Moving to the Coast

In the early 1870s, as the gold rush drew to an end, the family moved to New Westminster. Cumyow attended the same public school as Richard McBride, a school mate who was to become BC’s premier from 1903 to 1915. McBride travelled to an eastern Canadian university to study law at age 16. In contrast, Cumyow’s only route to further a legal education involved articling with white lawyers willing to hire him. He succeeded in working in two Vancouver law firms but was not permitted to take a bar exam because the BC Law Society only accepted candidates on the voters list, and people of Chinese heritage could not vote. (When Cumyow applied in 1903 to become a notary, the BC Law Society turned him down again for the same reason.) Cumyow continued to work in his father’s store in New Westminster and at the “Granville town site” as Vancouver was then called.

In the early 1870s, as the gold rush drew to an end, the family moved to New Westminster. Cumyow attended the same public school as Richard McBride, a school mate who was to become BC’s premier from 1903 to 1915. McBride travelled to an eastern Canadian university to study law at age 16. In contrast, Cumyow’s only route to further a legal education involved articling with white lawyers willing to hire him. He succeeded in working in two Vancouver law firms but was not permitted to take a bar exam because the BC Law Society only accepted candidates on the voters list, and people of Chinese heritage could not vote. (When Cumyow applied in 1903 to become a notary, the BC Law Society turned him down again for the same reason.) Cumyow continued to work in his father’s store in New Westminster and at the “Granville town site” as Vancouver was then called.

Scandal

In 1883, Cumyow moved to Victoria, which had a thriving Chinatown district, second only to San Francisco. He was employed as manager of the King Tye Company and was also secretary of the Chinese Benevolent Association. In 1885 the provincial legislature passed a series of discriminatory laws, including the imposition of a $50 head tax exclusively imposed on Chinese immigrants. An immigration translator was required and Cumyow applied.

However scandal erupted when Edward Johnson charged Cumyow of forgery. As a result, Cumyow lost the the translator job to American missionary, John Vrooman and was forced to resign his position with the King Tye company. Johnson claimed Cumyow put his name on a business transaction involving about $300, without his knowledge. After hearing the evidence, the police court judge turned the matter over to BC’s Supreme Court. On December 17, Cumyow was tried before Judge Begbie and at the end of a day’s testimony, the jury took only 20 minutes to render a guilty verdict. Cumyow was sentenced to three years in the BC Penitentiary. When the judge asked Cumyow if he had anything to say, he replied that the financial procedure had been manipulated and if he had known his trial was taking place so soon, he would have been prepared with a defence.

Given the racial discrimination of the period, the judicial system could have been biased against Cumyow. Not only was he accused by a “white” businessman but he was tried by an all-white, male jury. It is also doubtful the charge and sentencing would be regarded with the same level of severity in today’s courts.

Cumyow served his time at the New Westminster prison and integrated back into his dual English-Chinese communities, seemingly without bitterness. His punitive experience, which he never spoke publicly about, undoubtedly informed his future advocacy work.

Vancouver Pioneer

When Cumyow applied to be a police court interpreter in Vancouver, he was hired and held the position from 1888 until he retired in 1936 when his son Gordon replaced him. Cumyow had the background required, speaking fluently in English, Cantonese, Hakka (a dialect of Cantonese) and Chinook. He traveled as far away as Regina to interpret at a murder trial and journeyed by buggy with Justice Murphy to Barkerville. When his forgery conviction re-surfaced in 1903, threatening his work, Cumyow denied his involvement, stating the accused was his brother. Cumyow’s employer at the police court defended him and the potential scandal blew over.

Cumyow also ran a tea and coffee company in Vancouver and carried on various enterprises in New Westminster where the rest of his family still resided. His brothers had diverse occupations, according to the New Westminster directories of the 1890s, and were listed variously as a butcher, grocer, express man and clerk. Unlike Vancouver and Victoria, the Chinatown in New Westminster began to disappear. In the months after the great fire of 1898, members of the community had either integrated or left.

Cumyow was 28 years old when he entered an arranged marriage with 18 year old Eva Yea Chan, the daughter of a Methodist missionary from Canton. Cumyow and Eva left New Westminster and eventually found a permanent home at 1442 East First Avenue on Vancouver’s east side in 1909. The modest two-story wooden house (since torn down) was about a 20 minutes walk from Chinatown.

Cumyow was 28 years old when he entered an arranged marriage with 18 year old Eva Yea Chan, the daughter of a Methodist missionary from Canton. Cumyow and Eva left New Westminster and eventually found a permanent home at 1442 East First Avenue on Vancouver’s east side in 1909. The modest two-story wooden house (since torn down) was about a 20 minutes walk from Chinatown.

Cumyow’s father, now a widower, had seen three grandchildren born when he went back to Hong Kong in 1896 for a visit. He died there at age 80. Cumyow, who cultivated a relationship with newspaper reporters, ensured an article appeared about his pioneer father’s passing and contributions.

Photographs of the young Won Alexander show a thoroughly “westernized” and self-confident young man. He cut a lean figure, at 5 feet six inches, in a well-tailored suit. His dark hair was slicked back and his handsome facial features included a moustache as well as a small scar under his chin and on his forehead. When he smiled, he displayed a gold front tooth. On tour in the United States, Cumyow impressed a newspaper reporter who described him as “wide awake” and energetic. The reporter noted Cumyow wore a Panama hat and pink carnation in his lapel, and spoke English “readily.”

An Independent Man of Business and Law

Cumyow rented eleven different offices up to 1947, in building on Hastings, Granville, Homer, Carrell, Abbott and Main Street. This placed him within walking distance of the city’s business district. As a translator, he reported daily to the courthouse at Hastings and Cambie Street. After the courthouse was torn down in 1912, he ventured further west to a newly built courthouse (now the Vancouver Art Gallery) at Robson and Georgia Streets. Cumyow only had to translate as required and if he was too busy to interpret, he would send one of his sons. In the famous Janet Smith murder trial of 1924 for instance, Cumyow’s son Richard was the court interpreter for the accused Chinese house servant.

Cumyow’s business dealings reached as far as Alberta and Washington State. The Vancouver directory listed him variously as a tobacconist, wholesale dealer in “Oriental goods”, a real estate agent and business broker. He advertised himself in mainstream newspapers as a labor contractor, employing both Chinese and white labourers. As a contractor, Cumyow handled requests for cooks, land-clearers, wood-cutters, railway section hands and bakers. He was also a landlord and bought and sold real estate. One of his property transaction in 1893, involved pooling his funds with Sam Keen to buy buildings in Vancouver’s Chinatown. The business partners rented these buildings to Wing Sang and other merchants for over two years, before selling at a profit. All the while, in the 1890s Cumyow maintained the “Chinese Commercial Agency” in the New Westminster Chinatown with Kwing Wing Song.

Cumyow also worked for a time with mainstream employers, articling as a clerk in the law firms of O.L. Spencer and Taylor, Bradburn and Innes. Subsequently, Cumyow advertised himself as a student at law and a conveyancer. With his experience and contacts, Cumyow was among the city’s few bilingual residents to act as an “unofficial” legal adviser for the Chinese community.

An Advocate and Volunteer

Cumyow’s advocacy and volunteer work was extensive. In 1892, a small pox epidemic broke out and Cumyow wrote to Vancouver city council to request a “pest house” quarantine for infected Chinese. His request was referred to the Board of Health and provisions were made for patients on Deadman’s Island in Stanley Park.

Residents of Chinese heritage had been banned from volunteering in Canada’s military. Still Cumyow found a way to participate in the war effort in South Africa in 1900 by fundraising among merchants in Chinatown. In 1902, the Women’s Auxiliary of the Vancouver General Hospital asked for Cumyow’s financial help and he raised thousands of dollars within the Chinese-Canadian community for hospital construction, a goodwill gesture, considering the hospital’s discriminatory treatment. Up to 1920, patients were treated in segregated wards, a practice which was changed after a white woman married to a Chinese-Canadian merchant, successfully protested.

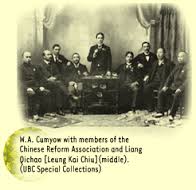

Cumyow helped found the Chinese Empire Reform Association (CERA) in Vancouver in 1899 and was its corresponding secretary. Branches already existed in Victoria and in towns in the province’s Cariboo district. Primarily run by older prosperous Chinese merchants, CERA opened the first Chinese school in Vancouver and produced a newspaper. The organization became well-known outside of Chinatown because members had influential contacts in government and business circles.

CERA was also influential in China’s affairs and believed in modernizing their ‘home’ country through progressive reforms. At the height of the Boxer Movement in 1900, Cumyow announced to local newspapers CERA was ready to send troops to China to accompany other foreign forces in order to release missionaries and diplomats besieged by anti-West Boxers. Soldiers from Canada were never sent, however.

Cumyow also participated in the Vancouver branch of the Chinese Benevolent Society and was its president in 1920. The organization’s mandate was to work against discriminatory immigration legislation, assist individuals living in poverty and support existing Chinese language schools. When a Chinese playground opened in 1928 behind the south east corner of Pender and Carrall Streets, Cumyow was there as a representative along with Mayor L.D. Taylor.

Cumyow had his share of contradictions. He campaigned for a democratic China but never visited—or desired to visit—the land of his ancestors. He spoke against vice, yet imported and sold opium before it was outlawed in 1908. Though he advocated for Chinese-Canadians, the majority of whom lived within the confines of Chinatown, he chose to live away from the area. Cumyow “didn’t want his kids to mix with certain elements in Chinatown” and he thought it was not a good place for children to go, according to his son Gordon.

Fighting for Full Citizenship

The franchise was taken away from Chinese-Canadians and First Nations people by the provincial legislation in 1875. This automatically disqualified these groups from having the federal vote. Yet Cumyow was able to stay on the voter’s list for a time because he was Canadian-born. In 1898 he was on the provincial voter’s list, listed as a merchant, living at 106 Canarvon Street in New Westminster.

In a letter to Thomas Cunningham, “collector of voters”, Cumyow appealed (for the second time) to be placed on the voter’s list of 1902. His request was ignored. This was a time when Japanese immigrants were arriving in large numbers. When a Japanese resident was denied the vote and challenged the provincial government, legislation was passed to ensure there were no exemption for exclusion among Asians.

Cumyow would have to wait 51 years before he would vote again.

Cumyow Speaks His Mind

Cumyow addressed the fears and prejudices of BC society in a presentation to a Royal Commission on Chinese immigration in 1902. “It seems to me that the Orientals are enabling the capitalists to carry on business which directly benefits all classes in the community,” he argued. The main reason Chinese live in separate quarters within BC communities, he said, is for “companionship.” “Besides the Chinese know that the white people have had no friendly feeling towards them for a number of years.”

Most Chinatown inhabitants were bachelors due to a head tax imposed exclusively on immigrants from China. Also, according to Cumyow, “a larger proportion of them would bring their families here, were it not for the unfriendly reception they got here during recent years, which creates an unsettled feeling.”

Cumyow spoke out against the head tax and in favour of granting the franchise. Chinese immigrants, Cumyow said, “should make valuable citizens and greatly aid in the development of this great country.”

As for the hostility against Asians, Cumyow stated: “In view of the agitation being carried on by politicians and professional agitators against the Chinese here, it is a mystery to me as it must be to other observers that so many people in all ranks of life are so ready to employ Chinamen to do their work.”

He suggested the anger is “more directed against the capitalists than against the Chinese themselves.” But hostility also exists, Cumyow said among “a large unthinking class who condemn them because it has become a custom to do so.”

Family Values

Cumyow ensured his children attended both public school and Chinese school. His son Gordon remembers spending five to six hours a day at Britannia Secondary School and then at 4:30 pm heading to Chinatown for Chinese school, and staying in class until 7:30 pm.

Gordon had been the first Chinese-Canadian student to study law at University of BC. He articled at a Vancouver law firm but left in 1918 after being informed he could not be called to the bar for the same reasons his father couldn’t —he was not on the voter’s list. The lawyer he articled with, J. Edward Bird, told him to fight it through the courts but Gordon declined and became a bank clerk at the Chinatown branch of the Bank of Montreal.

Cumyow’s daughter Aylene attempted to study nursing, but was also kept out. (The first Chinese-Canadian nurse did not graduate UBC until 1930.) “She finished high school and tried again and again to get into nursing school, but they wouldn’t take her,” Gordon said about his sister. “My dad tried all the well-known white doctors. No dice. My sisters wanted to get in too. But they couldn’t. After that, she took up stenography. But it was hard to get into an office also because they said, “We’re doing white people’s business, why would we hire Chinese?”

A sign of veneration

In November of 1939, the Cumyows celebrated their golden anniversary with seven of their ten children present. A month later, Cumyow’s wife, aged 68, died after a short illness.

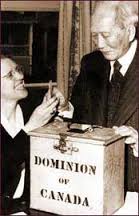

After the Second World War, the vote was extended to include Chinese-Canadians in 1947. Two years later, Cumyow, aged 86, cast his ballot in the federal election and was famously photographed “making history.” The New Citizen, a Chinese-Canadian magazine, stated: “During the 51 disenfranchised years, Mr. Cumyow has worked incessantly to have this injustice remedied.”

After the Second World War, the vote was extended to include Chinese-Canadians in 1947. Two years later, Cumyow, aged 86, cast his ballot in the federal election and was famously photographed “making history.” The New Citizen, a Chinese-Canadian magazine, stated: “During the 51 disenfranchised years, Mr. Cumyow has worked incessantly to have this injustice remedied.”

Cumyow’s sons and their families resided at various times at his residence in his widower years, as was customary in Chinese culture. Cumyow was not only an elder of his family, but of Vancouver too. He told an inquiring newspaper reporter he kept up his interest in civic and national affairs by studying five newspapers and several periodicals which came regularly to his home. Cumyow also said was one of the earliest subscribers to the Daily Province when it was a weekly published in Victoria and owned by the late Senator Hewitt Bostock.

On March 26, 1951 Cumyow celebrated his 90th birthday. A Province reporter wrote about the gathering of his children, eight grandchildren and 150 friends. “Dapper, bright and alert,” the reporter wrote, “Mr. Cumyow says his recipe for long life is ‘everything in moderation, and knowing how to keep your temper.’ Doctors said his heart was good and his only infirmity is hearing.”

“When interviewed the day after his birthday,” the reporter observed, “Mr. Cumyow was talking in a whisper. He’d been so excited, he’d lost his voice. But a good drink of Scotch helped that.”

Cumyow also said rye was his favourite whisky and that he smoked cigars—moderately. He liked the occasional western dinner as well as Chinese food.

“The older a Chinese gets”, Cumyow also said, “the more years his friends attribute to him, because age is a sign of veneration.”

A month after his birthday, Cumyow’s son Gordon became a notary public. “Despite her flaws and shortcomings, Canada is still the best country on earth,” Gordon told the local press. “We’ve come a long way since the day when we weren’t even recognized as citizens, let alone choose any profession as we pleased.”

In May of 1954, the city of Vancouver held an anniversary for its pioneers in Stanley Park. Cumyow, aged 94, qualified as he was among those to settle in the city before the first train from Montreal arrived in 1887. Unable to attend because of his health, Cumyow sent his good wishes to the 103 guests.

Later that same year, Cumyow died in the hospital on October 6, 1955. He was survived by five sons and three daughters, eight grandchildren, two great-grandchildren and a brother, Frank. The Vancouver Sun ran an article with a photograph, and recognizing his legacy, described Cumyow as a “highly-respected…leading figure in the local Chinese community…who strived for better relations and understanding between Chinese and English-speaking communities in Canada.”

*

Sources

Books

Chan, Anthony. Gold Mountain: The Chinese in the New World. (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1983).

Morton, James. In the Sea of the Sterile Mountain: The Chinese in British Columbia. (Vancouver: J.J. Douglas, 1977).

Reimer, Derek, ed. Opening Doors: Vancouver’s East End. (Victoria: Provincial Archives of British Columbia, 1979), pp. 15-20.

Roy, Patricia. A White Man’s Province: BC Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858-1914. (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1989).

Wickberg, Edgar, editor, From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities of Canada,” McClelland and Stewart, 1982.

Wickberg, Edgar. “Chinese and Canadian Influences on Chinese Politics in Vancouver, 1900-1947” in BC Studies, No. 45 Spring, 1980, pp 37-55.

Wright, Richard Thomas. In a Strange Land: A Pictorial Record of the Chinese in Canada, 1888-1923. (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1988).

Yee, Paul. Chinese Business in Vancouver: 1886-1914. Department of History, MA Thesis, University of BC, 1983.

Yee, Paul. “The Chinese in Early Vancouver” in BC Studies, No. 62, Summer, 1984, pp. 44-67.

Yee, Paul. Saltwater City: An Illustrated History of the Chinese in Vancouver. (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 1988).

Newspapers

The New Citizen, Vancouver.

Vancouver World, Vancouver.

Vancouver News-Advertiser, Vancouver

Vancouver Daily Province, Vancouver.

Victoria Daily Colonist, Victoria.

Victoria Daily Standard, Victoria.

Victoria Daily Times, Victoria.

Other Sources

Won Alexander Cumyow papers, Special Collections, University of BC. Donated by Mrs. Hilda Cumyow and Ms. Aileen Cumyow.

Report on the Royal Commission of Chinese Immigration: Report and Evidence, Ottawa, 1885.

Report on the Royal Commission of Chinese and Japanese Immigration: Report and Evidence, Ottawa, 1902 (See Won Alexander Cumyow’s submission to the commission, pp. 235 and 296.)

Interview with Won Alexander Cumyow’s granddaughters, Aileen and Marilyn Cumyow (daughters of Gordon Cumyow), November, 2004.

Vital Statistics, BC Archives, Victoria, BC.

BC Voter’s List, BC Archives, Victoria, BC.

Chinatown Heritage Alley website – http:://www.chinatownvancouver.ca/

Henderson Directory of Vancouver and New Westminster.

[This article has been revised, originally appearing in the Chinese Canadian Historical Society of BC newsletter (2008). More information about the society is available at http://www.cchsbc.ca. ]

*

Janet Mary Nicol is a secondary school history teacher in Vancouver and a freelance writer. She has written local histories about Vancouver and its people for BC History, Canada’s History and Labour/Le Travail. She also volunteers with the BC Labour Heritage Centre. Her writing blog is at http://janetnicol.wordpress.com/

Janet Mary Nicol is a secondary school history teacher in Vancouver and a freelance writer. She has written local histories about Vancouver and its people for BC History, Canada’s History and Labour/Le Travail. She also volunteers with the BC Labour Heritage Centre. Her writing blog is at http://janetnicol.wordpress.com/

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster