#66 No country for old media

No News is Bad News: Canada’s Media Collapse — and What Comes Next

by Ian Gill, foreword by Margo Goodhand

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2016

$18.95 / 9781771642682

Reviewed by David N. Wright

First published Dec. 21, 2016

*

Ian Gill’s No News is Bad News. Canada’s Media Collapse — And What Comes Next is a dense commentary on the state of media and journalism as currently practiced in Canada.

Ian Gill’s No News is Bad News. Canada’s Media Collapse — And What Comes Next is a dense commentary on the state of media and journalism as currently practiced in Canada.

A former reporter and editor for the Vancouver Sun and the CBC, Gill laments the collapse of the Canadian media and makes little attempt to hide his indignant tone. “Canada’s journalism is in ruins, and our nation is the poorer for it. Just look around” (48).

From the beginning, Gill lays out the paradigm for his critical survey of the Canadian media landscape, noting that “For me, a former newspaper journalist, what is happening to Canada’s newspaper industry feels personal, which might partly explain why my distress at the parlous state of Canadian newspapers veers toward the intemperate. I feel like we are being robbed blind, mugged by the oligarchs, and fed a diet of content you wouldn’t serve in a hospital during a power outage” (3).

No News is Bad News is divided into an introduction and four chapters, each of them devoted to a particular aspect of current news media and journalistic practice.

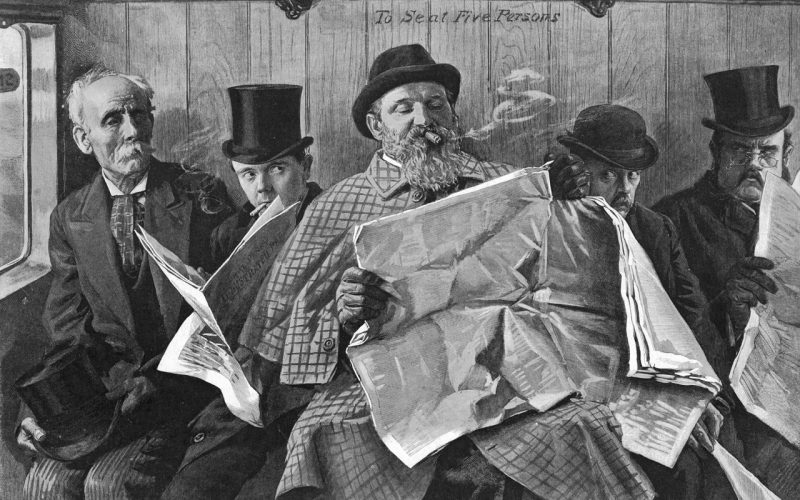

The introduction and first chapter deal primarily with that most traditional mode of journalistic enterprise, newspapers. Chapter 1, “No Country for Old Media: Our Shrinking Public Square,” taking up nearly one-third of the book, addresses what Gill sees as the perilous and decrepit state of Canadian media and journalism. He considers the death of newspapers as a primary space for journalistic practice and laments the current state of the Canadian news media landscape, especially the loss of local news and the increasing dominance of large, mainstream, corporate-model news outlets that tend to underserve minority populations while catering to a sometimes dubious corporate narrative that encourages biased viewpoints over objectivity.

The middle chapters — “What’s Happening Across the Pond?” and “What’s Happening Closer to Home?” — turn outward and examine how news media and journalism work in other places, particularly Europe, and how reportage must adapt and change to remain viable in what appears to be an uncertain and increasingly bleak future.

Gill surveys emerging journalistic practices and emphasizes how journalism and its institutions, both in Canada and abroad, are leveraging technology, philanthropy, and savvy user-pay funding processes to revive the industry.

Gill’s best is Chapter 4, “Whither the Future.” His rhetoric is reasoned, his purpose clear, and he has repressed all his earlier bitterness of tone associated with what he sees as the collapsing foundations of Canada’s media establishment.

His gaze now turns to representation, particularly indigenous representation in news media, and how journalism can be sustained in Canada by adopting new models, perhaps looking toward organizational models such as VICELAND, Neiman Labs, and The Knight Foundation, among many salient examples.

On the whole, No News is Bad News never really settles on a clear subject. Instead, it manoeuvres briskly through many different takes on news media, sometimes confusing the institutions of news media with the practice of journalism, so that one is not quite sure where the issues lie, or with whom. Gill presents an often-fractured rhetorical development that never quite allows a clear line through the mire.

Gill is careful to qualify his position, pointing out that “my time outside of mainstream journalism has given me a more multi-faceted view of the media than being a lifer would ever have allowed” (15) — but I am not sure that his polemic can be taken as a “multi-faceted view.”

His commentary focuses almost exclusively on print, particularly newspapers, and The Toronto Star, The National Post, and The Globe and Mail all receive much attention. Gill is most interested in how these “legacy media” are transitioning into online venues. He provides hurried critiques of other spaces for news media, such as radio and television, and institutions such as Postmedia and the CBC, but such analysis is sparse and the arguments not as developed as when Gill takes on newspapers or the emerging spaces for long-form journalism on the internet.

At times, Gill is a little too glowing about left-leaning media outlets such as the Guardian, Canadaland, and Discourse Media. At face value, there’s nothing wrong with this positivity toward progressive journalism. However, given his frequently harsh asides about the former Conservative government, Postmedia, and other outlets for their conservative agendas, Gill’s obvious bias towards arenas with more liberal agendas taints the integrity of his critique of the right.

No News is Bad News is full of rhetorical flourishes that sometimes distract from what is generally a well-researched survey of the admittedly sparse and collapsing news media landscape. Concerning a robot journalist, Gill writes that such a machine “should send a shiver down the spine of whichever journalists are left who still have one;” and after critiquing a quote about the state of television news by The Globe and Mail’s television critic John Doyle, Gill opines that he “may yet find himself satiating his hunger by eating those words” (59, 62).

And venturing that “It’s hard to imagine journalistic standards sinking much lower” in the deployment of news-like advertisements in newspapers and magazines, Gill suggests “that is a thought best served hold” (60). This is not a typo for “cold.”

Readers certainly deserve flair and panache in essays, but Gill’s prose sometimes feels forced and his characterizations veer perilously close to the very rhetorical bombast that is beginning to dominate current political narratives, and which might well turn readers off.

But on the whole, Gill’s analysis is well researched, intelligent, and offered by an insightful and reasoned individual. When he ends the book with a glance at the possibilities that philanthropy and emerging Internet media might play in reviving journalism and enticing a distanced readership, he shows himself to be a thoughtful commentator on the future of journalism.

Indeed, when Gill restricts the idle tongue-lashing and passive aggressive tone, and addresses issues of inclusiveness in Canadian news media, No News is Bad News rises to remind readers of the power of journalism. And when he reminds us that “We need to become our own champions again,” it’s hard not to forgive his rhetorical bombast. His conclusion is both trenchant and urgent: “We need to change the collective imaginary and find powerful new ways to mobilize it so that everyone sees at least some of themselves in Canada’s evolving story” (149).

*

A faculty member of the English Department at Douglas College in New Westminster, David N. Wright leads the Digital Cultures Lab there. His current research and teaching emphasize the role of critical thinking and close reading in understanding, using, and building digital tools and emerging technologies.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Wade Davis, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster