#63 An Imperial crackpot in BC

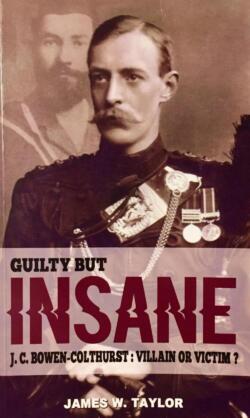

Guilty But Insane. J.C. Bowen-Colthurst: Villain or Victim?

by James W. Taylor

Cork, Ireland: Mercier Press, 2016

€14.99 / 9781781174210

Reviewed by Joe Simpson

First published Dec. 14, 2016

*

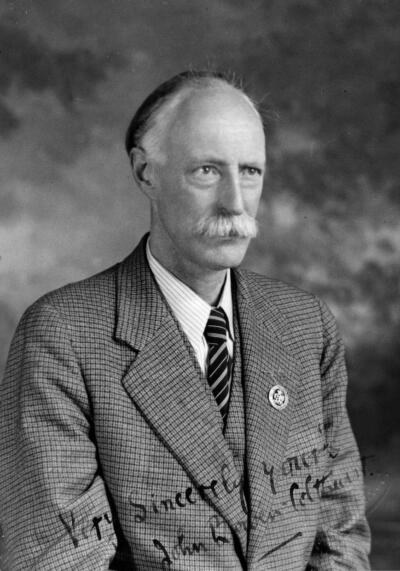

In Guilty But Insane, James W. Taylor traces the life of British Army officer Captain John Bowen-Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles.

In Guilty But Insane, James W. Taylor traces the life of British Army officer Captain John Bowen-Colthurst of the Royal Irish Rifles.

A veteran of campaigns in India, Tibet, and South Africa, he was badly wounded at the Battle of Aisne River in 1914 in the early months of the First World War.

Having recovered from his wounds, he continued to suffer from “extreme battle stress” and was relegated to garrison duties at Dublin.

Described by reviewer Joe Simpson as “the classic wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time,” Captain Bowen-Colthurst embarked on a campaign of extra-judicial killing in the “Easter Rising” in Dublin in April 1916.

Taylor traces Bowen-Colthurst’s short and murderous flame of infamy in his native Ireland followed by his trial, at which he was found “guilty but insane.” After a year in an insane asylum he was permitted to move to British Columbia, where he led a long and uneventful life in which he dabbled in farming, politics, and writing letters to the editor.

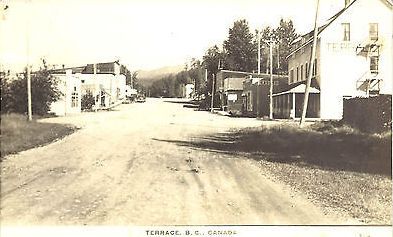

Between 1919 and his death in 1965, he lived at Milne’s Landing (Sooke), Kitsumkalem and Lakelse Lake (near Terrace), and Naramata (Penticton) — Ed.

*

Guilty — But Insane? Back in June 2003, working away as usual in my Duncan, Vancouver Island law office, I received an email from Jim Herlihy, genealogist and official historian of An Garda Siochana, the police force of the Republic of Ireland. At the time Jim was still an Inspector with the Gardai. We had been in touch for some time on mutual Hiberno-Canadian historical interests, and this time Jim had something new on his mind.

The people of Carrigadrohid in Co. Cork, at the southern end of Ireland, were trying to track down the title deeds for a semi-ruined ancient fortification in their small community so that they could apply for a European Community (EU) heritage grant to restore the ruins and attract tourists. The land on which it stood still belonged to the Bowen-Colthursts, an old Anglo-Irish “Protestant Ascendancy” family long gone from the Cork area. It was rumoured that descendants might be living in British Columbia, where a controversial member, one Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst, had emigrated some eighty years before.

A thirty-five year old British Army officer serving with his regiment in Dublin City at the time of the April 1916 “Easter Rising,” Bowen-Colthurst apparently became mentally unhinged and had shot dead a number of unarmed, innocent civilians unconnected with the five-day insurrection. At his ensuing court-martial he had been found “guilty but insane.” After a spell of confinement in an English “lunatic asylum” he had been released and later moved to British Columbia with his wife and children. Perhaps, Jim Herlihy wondered, the Carrigadrohid castle title deeds had also gone to Canada and still existed? The local community back there hoped so, and had sought the help of Jim himself from Co. Cork, to track down the missing deeds.

Jim’s question to me was this: did I happen to know of any Bowen-Colthursts still living in British Columbia? There was once a Judge Bowen-Colthurst based in my part of Vancouver Island before my time there, I soon discovered, but he had been long retired before his death in 1997. An online search soon struck gold, however — the website for a lakeside resort near Terrace, B.C. owned by a family of the same surname. I emailed the contact information back to Jim, and thought little more about it.

Until one morning just over a year later, that is, when another email from Jim in Ireland landed in my computer inbox:

My letter to the Bowen-Colthursts has worked. We had a wonderful letter today from the daughter of Captain John Bowen-Colthurst by his second marriage … [she] is travelling to Belfast in September to hand over her father’s medals to a regimental museum there and is prepared to travel to Cork to sign the necessary paperwork to hand over Carrigadrohid Castle to the community group there and will also hand over family papers to the local library.

Which is what duly happened later that autumn of 2004, when by all accounts a delightful lady in her early sixties from Spokane named Georgiana Sutherlin, née Bowen-Colthurst, travelled for the first time to her ancestral homeland. Notwithstanding the long-remembered Royal Irish Rifles incident of 1916 involving her late father, she was warmly received by the folk of Carrigadrohid. And in due course, with the proper paperwork in hand, the community received its EU grant.

A dozen years on, amid a small avalanche of printed works published to coincide with the first centenary of the 1916 Dublin Easter Rising, we now have a balanced and carefully-researched study of Captain John Bowen-Colthurst and his disastrous role in that event.

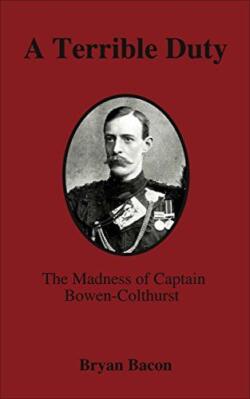

James W. Taylor, FRHS, a retired Republic of Ireland civil servant and published military historian, is the author of the exhaustively-researched Guilty But Insane — J.C. Bowen-Colthurst: Villain or Victim? published in 2016 by Mercier Press of Cork. It is a useful companion piece to a downloadable eBook (available through Amazon) published in 2015 by Thena Press. Edited by B.C. resident Jonathan O’Grady, and based on the extensive research of his friend Bryan Bacon, who died in 2005, it has the equally arresting title, A Terrible Duty: The Madness of Captain Bowen-Colthurst (Thena Press, 2015).

Unlike the O’Grady-Bacon writing team, James Taylor has accessed the Bowen-Colthurst private family papers held by Georgiana Sutherlin and also obtained uniquely fascinating insights from both Georgiana and her husband Douglas. Taylor’s stated objective is to present a “balanced view” of the much-demonized Anglo-Irishman “Jack” Bowen-Colthurst, who died in his mid-eighties at his home in Naramata in 1965.

Unlike the O’Grady-Bacon writing team, James Taylor has accessed the Bowen-Colthurst private family papers held by Georgiana Sutherlin and also obtained uniquely fascinating insights from both Georgiana and her husband Douglas. Taylor’s stated objective is to present a “balanced view” of the much-demonized Anglo-Irishman “Jack” Bowen-Colthurst, who died in his mid-eighties at his home in Naramata in 1965.

Taylor’s stated goal is to present the “available evidence” as objectively as possible so that his readers can reach their own “informed conclusions.” In this reader’s humble opinion he succeeds in that challenging task admirably. His book has surely been many years in the making, as I have another 2004 email from Jim Herlihy that mentions his friend “Jimmy Taylor” working on a book about John Bowen-Colthurst.

Guilty But Insane first examines its main subject’s early life as a privileged scion of the late-Victorian era Anglo-Irish Protestant Ascendancy — a term that refers to the dominant class of Church of Ireland or Church of England landowners and clerics — expensively educated at a tony “public” (private) school in England before graduating almost top of his class at Sandhurst, the prestigious British Army military academy.

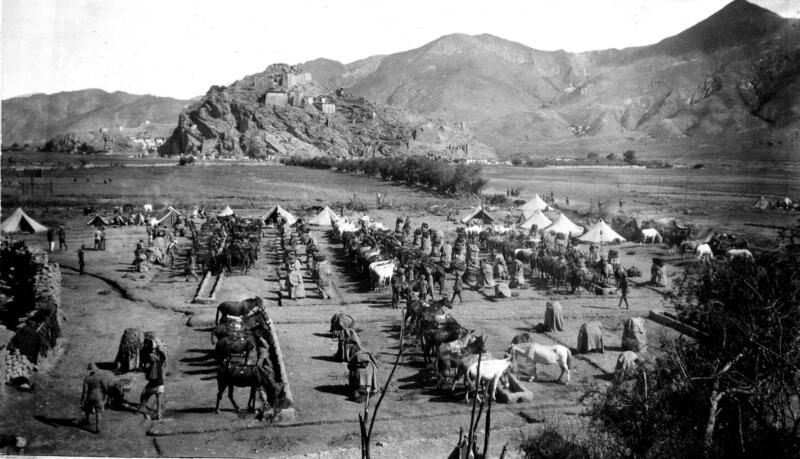

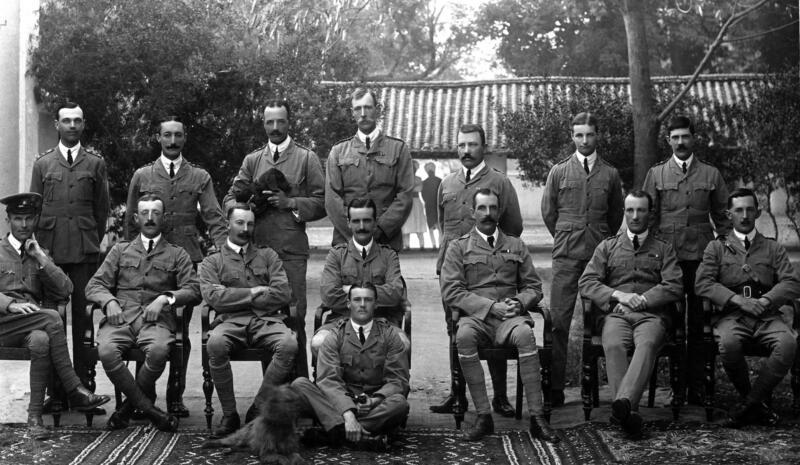

Taylor then covers Bowen-Colthurst’s promising early career as a commissioned junior officer with the Royal Irish Rifles in South Africa (1899-1901 Boer War), Tibet (the 1903-4 “punitive expedition” led by Francis Younghusband), and Imperial British India before being posted, as a newly-promoted captain, back to his native Ireland for “home service” in 1908.

The only “blip” in his smooth pre-1914 career with the army occurred in South Africa, when as a prisoner of war he had to surrender his weapon to a Boer commando fighter who just happened to be an Irish nationalist from his own part of Co. Cork! Taylor notes an ominous early warning sign of Bowen-Colthurst’s hidden vindictive streak. It came when, after release by advancing British forces from a mere six weeks in Boer captivity (when he was treated far more humanely than the British had been treating Boer civilians in their later-to-become-notorious “concentration camps”), he went around “knocking old Burghers down” — as he proudly recounted in a letter home. A burgher was a farmer of Dutch descent.

The Great War took Bowen-Colthurst with his regiment to the Belgian-French border soon after the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914, and he took part in the Mons Retreat following the Battle of Mons. By October of that year he was back in Ireland after being badly wounded in combat at the Aisne River. Despite recovering physically by Spring 1915, he was deemed unfit for active front-line service due to his nervous excitability under extreme pressure.

Relegated, as a once-promising officer, to dull progressively less productive garrison and recruitment duties in the Dublin area, in hindsight Bowen-Colthurst was, to quote Taylor, a “mental powder-keg ready to blow up.” And explode he duly did when — seemingly out of the blue and totally unexpectedly for all but a relatively small cadre of conspirators — during Easter Week 1916 Dublin’s city centre was consumed by intense street-fighting between a few hundred Irish republicans and British forces.

Based at Portobello Barracks during the chaotic few days of the nationalist rebellion, with his CO on sick leave, Bowen-Colthurst was the classic “wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Not only that, but the British Army was totally untrained for urban warfare against their own civilians. Ordered to occupy a nearby tobacco shop thought (wrongly) to belong to a rebel sympathiser, Capt. Bowen-Colthurst and his men, against all military protocol, took along as a “hostage” the recently-arrested Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, a Dublin journalist, pacifist, and well-known anti-imperialism propagandist sympathetic to nationalist aims but unconnected with the uprising.

After impulsively shooting dead several innocent passers-by in the street, and arresting two other civilians found at the targeted store, Bowen-Colthurst brought all three prisoners back to the barracks. No amount of evidence to the contrary could convince him that these harmless individuals were not dangerous subversives. Unable to sleep after going to bed at 3:00 a.m. the overwrought Captain (a religious fundamentalist since his India days) read Luke 19:27 in his Bible: “But those mine enemies, which would not that I should reign over them, bring hither, and slay them before me.” In his increasingly fragile mental state, Luke’s admonition seemed like a directive from the Almighty.

What happened at the Barracks the next morning makes for excruciating reading even a century later. Taylor presents the atrocious facts as evenly as possible. Bowen-Colthurst had all three civilian prisoners led out under armed guard to a small enclosed yard behind the barracks, and without warning had them all shot to death. Soon afterwards he told a superior officer at the barracks that he had acted on his own responsibility and “might hang for it.” In a written report later that day he falsely asserted that incriminating subversive documents had been found on the three men.

A brutally invasive search conducted soon after the murders by Capt. Bowen-Colthurst and his men of the murdered Sheehy-Skeffington’s family home in the presence of his terrified widow Hannah and their 8-year-old son Owen, when the Captain frantically searched the house for evidence of his subversive activities, produced nothing incriminating because there was nothing of that nature to find.

Taylor consulted about this behaviour pattern with a leading Belfast psychiatrist who gives his expert opinion that John Bowen-Colthurst in April 1916 displayed “significant and substantial dissociative symptoms.” High levels of stress likely triggered an “ego state switch” from normal to a setting of extreme fear and imminent threat perception. Bowen-Colthurst may have already suffered from some form of post-traumatic stress disorder after his experiences at the front in September 1914. Once his “normal ego state” had returned, his latent feelings of guilt or shame at what he had just done led him to manufacture false evidence as an adaptive self-preservation technique. If true for Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst, this retroactive diagnosis may solve the apparent conundrum of how he could have been legally “insane” when he committed the murders, yet immediately afterwards been capable of finding ways to present his lethal behaviour as rational and even necessary.

Self-exculpation and a brooding sense of unfair victimization by his superiors combined to provide a protective mental cocoon for John Bowen-Colthurst over the next half-century until his death aged 85 in Penticton. Mentioned in both the Taylor and O’Grady-Bacon books is a 1959 interview that he gave at his Naramata home to The Penticton Herald. In that interview the “old warrior” coolly stated that he had “verbal orders” to shoot Sheehy-Skeffington after finding “incriminating documents” on the Dublin journalist.

Of course both those self-justificatory claims were counter-factual. By his own spoken admission to his immediate superior officer at the barracks shortly after the murders there, he had acted of his own accord. And when first arrested in the street early in the uprising by Capt. Bowen-Colthurst, the civic-minded Frank Sheehy-Skeffington was merely distributing anti-looting leaflets. For good measure in the same press interview the wily but delusional old soldier told the reporter that he absolutely had “no regrets for doing his duty” by having his prisoners shot. It was fortunate indeed for him that internet search engines had not yet been invented.

Contrary to various conspiracy theories repeated over the intervening hundred years by many commentators (including some academic historians), Taylor does not find even circumstantial evidence of a plot by the authorities to cover up the Portobello Barracks murders, and to let the perpetrator escape punishment. A successful cover-up would have been impossible anyway, given the establishment connections of the Sheehy-Skeffington family. The Irish Party at Westminster bombarded Asquith, the Liberal PM, with questions about the Sheehy-Skeffington murder, and Taylor speculates that this parliamentary furore may have saved from execution Eamon de Valera, a future President of Ireland, more than de Valera’s dual Irish-US citizenship.

As a lawyer, I found Taylor’s book especially interesting on the legal aspects of Bowen-Colthurst’s June 1916 court martial in Dublin. The UK Army Act forbade a court martial of a military member accused of committing an offence within the United Kingdom — unless a state of martial law remained in effect at the time of the trial, which was no longer the case by June. Yet the British Government, for what Taylor notes to be sound enough reasons with the July 1916 Somme Offensive about to begin and with 200,000 Irish troops fighting for Britain along the Western Front, feared the effect on morale of a murder trial with an Irish jury (and by law it would have had to take place in Ireland). There was also alarm over the potential for a more widespread, possibly German-backed, Irish rebellion at England’s back door. Top legal minds soon cobbled together a “duct tape” solution by adding two new regulations to the UK Defence of the Realm Act not only to allow civil offences to be tried by a court martial, but to preclude a civil trial after a court martial, as the Army Act was silent on that issue.

And so Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst at the Richmond Barracks in Dublin on June 6, 1916 faced the first General Court Martial to be held on Irish soil since the end of the Napoleonic Wars a hundred years before. He was charged under the Army Act with the triple murders of Frank Sheehy-Skeffington and the two other victims of his firing squad, and also with the lesser offence of their manslaughter, at Portobello Barracks on April 26, 1916.

Bowen-Colthurst did not take the stand, but his former wartime CO, Major-General Bird, testified as to his courage, high ideals, “deep religious convictions,” and, crucially for the defence, about two specific occasions during the 1914 Mons Retreat and soon afterwards the battle at the River Aisne. On both those occasions the defendant, fatigued by lack of sleep and under extreme battle stress, reportedly became over-excited and lost his rationality, recklessly risking the lives of himself and his men in the process.

Maj-Gen Bird’s mitigative evidence was anxiously sought by the desperate Bowen-Colthurst family before the trial. This, along with expert medical opinion and testimony from others present about his peculiar and excitable behaviour before and immediately after the barracks murders, went a long way towards saving the Captain’s neck by enabling the oxymoronic verdict of Guilty But Insane. (The 1883 Trial of Lunatics Act created this new verdict at the request of Queen Victoria, a frequent target of mentally-ill would-be assassins, who thought that replacing the old Not Guilty But Insane verdict would deter such attacks.)

In light of Bowen-Colthurst’s comment just after the murders that he “might hang for it,” the verdict might well have been different in a civil (as distinct from military) court trial where the insanity defence might have been more rigorously tested by the prosecution. In a 1952 murder case called R. v. Windle, the accused had given his wife a lethal aspirin overdose. When arrested he had told the police, “I suppose they will hang me for this.” The trial judge found that even though mentally ill, that statement proved that the husband knew he was committing a crime. On that basis the Judge refused to grant the Guilty But Insane verdict, and sentenced him to hang.

Ironically, as Taylor’s book reveals, Bird’s helpful, even life-saving, evidence at the court martial came back to haunt him when John Bowen-Colthurst, ever convinced that he had been made a scapegoat, obsessively subjected the retired major-general living in England to a campaign of harassment from B.C. in the form of a series of increasingly unpleasant letters before Bird’s death in 1943.

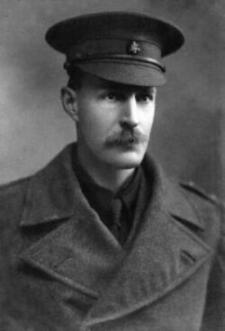

The Dublin court martial verdict meant “indefinite” confinement under s. 130 of the Army Act for Bowen-Colthurst in England’s Broadmoor Asylum as a “criminal lunatic.” An identity photograph of him taken when he arrived at Broadmoor, reproduced in Taylor’s book, shows a shattered man looking far older than his thirty-five years. There he remained until his release to a Surrey private asylum in early 1918 after lobbying from influential family friends. Taylor tells us that his medical examiners there assessed him to be “mentally normal” but with “a highly nervous and erratic disposition.” Within a year he was free. Based on his extensive researches however, Taylor discounts a long-held conspiracy theory about a British Government plot to set Bowen-Colthurst free after a token spell in confinement.

In March 1919 Bowen-Colthurst wrote to the Home Office about his desire to move to British Columbia, Canada. The family already had a connection there — his wife’s brother had given her a small acreage in Sooke, near Victoria, BC as a wedding gift in 1908.

In May 1919 Bowen-Colthurst arrived alone in the small city of Duncan, Vancouver Island. Possibly he had old military comrades living there, as the Cowichan Valley was by then a popular retirement destination for Indian Army officers, imperial civil servants and the like. Duncan also had (and still has) a Masonic Temple. Bowen-Colthurst had been a Freemason ever since his time in India.

In March 1920 he was back in England with his family preparing for final emigration. In July 1920, the Irish Republican Army burned down Oakgrove, Bowen-Colthurst’s family home, very likely in reprisal for the 1916 murders. Ex-British Army Irish war veterans were being shot. Obviously return to Ireland was not an option.

Soon he was back in B.C., and in the 1921 census for Terrace, he is listed as a “carpenter” and – before his family joined him from England – he worked for a season as a labourer building the Kalum wagon road in the Skeena Valley. This seems to have been the only paid work he did during his life in Canada. A photograph from this time reproduced in the O’Grady-Bacon book, from the City of Terrace Collection, shows a roughly-clad Bowen-Colthurst on Dominion Day 1921 standing in a group of other men beside a “Great War Veterans” parade float. A world away from the immaculately-uniformed, intensely serious imperial soldier of his pre-1908 Indian Army photographs, he looks casually relaxed and rather jovial.

By 1924 Bowen-Colthurst, his wife Rosalinda and their three young children were finally settled in Kitsumkalum, west of Terrace in the Skeena Valley, supported in part by his modest military pension. The circumstances of their admission to Canada, strictly illegally as Bowen-Colthurst failed to declare his history of “insanity” and confinement in a lunatic asylum (which could have automatically disqualified him from entry), make for very interesting reading in O’Grady and Bacon’s A Terrible Duty. He even claimed in his Ship Passenger Declaration to be returning as a “Canadian Soldier Settler.” Invisible helping hands back in England may have been at work here, for as O’Grady sardonically notes, in the early 1900s Western Canada was seen there as a remittance man’s haven and “colonial warehouse for unwanted goods which would be stored indefinitely.”

Both the Taylor and O’Grady-Bacon books, especially the latter, provide many interesting and often colourful details about John Bowen-Colthurst’s eccentric trajectory through the last four decades of his life in various parts of British Columbia. For all his oft-repeated claims to have a large price on his head and be on the run from a vengeful IRA (and there does appear to have been one near-miss in 1955 when a would-be assassin was foiled by the BC police, who then put his family under temporary protection) he did not exactly hide his light under a bushel. He dabbled very publicly at times in BC provincial politics and for decades was a prolific writer to the press on whatever topic of the moment he cared to sound off about – and there were a great many over the years. He may have been damaged goods, as O’Grady and Bacon suggest, but John Bowen-Colthurst was not introverted or guilt-ridden.

In contrast to his maladaptivity to fatigue and combat stress that ultimately caused the ruin of his military career, John Bowen-Colthurst readily and enthusiastically adapted to life in the remote Skeena Valley, which he took to like the proverbial duck to water. While Rosalinda slaved away at her domestic chores, her husband was often away for long spells on hunting, shooting, and fishing expeditions – just as he often did during his peacetime bachelor army days in northern India stationed near the Himalayan foothills.

Taylor cites the written 1938 account of a niece from England, who visited the Bowen-Colthursts at their new home in 1925, describing their primitive living conditions — mud everywhere, a cabin without piped hot water, and an open wood fire for cooking. Initially, outside visitors were few, such as the “Chinese laundryman” who came once a week, and an itinerant preacher who dropped by occasionally. Over time, however, Capt. Bowen-Colthurst became known as a colourful character, and did nothing to discourage a flatteringly misleading rumour (he possibly started it) that as a result of being on the “wrong side” of the Irish Question he had been forced to escape from nationalist rebels who had put a $10,000 price on his head, by being “smuggled” into an insane asylum by his friends. He was said to have disguised his features for a while by growing a beard.

One anecdote cited by Taylor, if true, reveals a less than flattering aspect of the charismatic, newly-minted Canadian John Bowen-Colthurst’s multi-faceted personality. According to this story, in 1927 he borrowed a piece of farm equipment from a fellow-immigrant neighbour, and accidentally broke it. He refused to pay for its repair, and the owner (who presumably knew something of his past) angrily threatened to send some Irish “Sinn Feiners” living in the neighbourhood to sort him out! In short order, the story goes, Bowen-Colthurst paid up and asked that the “Sinn Feiners” be told nothing about him.

Another, rather more amusing anecdote from the mid-1920s recounted by O’Grady-Bacon, concerns bewildering late-night calls at the (highly religious) Bowen-Colthursts’ new home by lonesome men passing through. Evidently there had been a bordello on the same property a few years earlier to entertain construction workers on the new railway line through the Skeena Valley!

In 1925 Rosalinda Bowen-Colthurst, who seems to have had her own, separate financial resources, bought for $600 a sixty-acre property registered in her sole name at Waterlily Bay on nearby Lakelse Lake. It became known in the family as “Mummy’s Land”. Her husband soon built a summer cabin on this recreational property which remains in the Bowen-Colthurst family and is now the tourist resort mentioned earlier in this review. The following year Rosalinda acquired for a nominal sum a quarter-interest in just over 300 acres nearby with water rights and a natural hot spring. John Bowen-Colthurst then, like his near-contemporary Grey Owl (1888-1938) in another part of Canada, bought trap line rights next door on the edge of Lakelse Lake. As O’Grady/Bacon remark, “his adaptation to local ways was remarkable.”

Around 1929 the Bowen-Colthursts moved to the much less remote Milne’s Landing on southern Vancouver Island, the Sooke property gifted to Rosalinda by her brother back in 1908. At just under four acres, the rural lot had a modest frame house and a small cabin. They called it “Coolalta” after their old home area in Co. Cork. Summers were still spent at “Mummy’s Land” up north at Waterlily Bay.

According to Taylor, it was around this time that Capt. Bowen-Colthurst began his aforementioned compulsive habit of writing strongly-worded and increasingly menacing letters to his wartime CO, retired Maj-Gen Bird. In particular he obsessed about Bird’s 1915 damning report to the War Office criticizing Bowen-Colthurst’s impulsively leading his Royal Irish Rifles company in a foolhardy and costly assault at the Aisne River in late 1914 against Bird’s strict orders to hold back. Ironically, it was this report, which also mentioned Bowen-Colthurst’s suicidal (but fortunately short-lived) attempt earlier to turn his small company around to attack the advancing Germans during the 1914 Mons Retreat, that had greatly helped Bowen-Colthurst to get his life-saving “guilty but insane” verdict in 1916.

In far-away England, Bird sensibly avoided responding to the toxic flow of letters, instead forwarding them to the War Office in London, as the poor man was getting increasingly anxious from their angry tone that Bowen-Colthurst might personally show up on his doorstep to take revenge on the older man for “ruining my career.” Taylor observes that it is revealing of Bowen-Colthurst that he included, in a long list of his heroes in one particularly rambling 1936 letter sent to Bird, the name of General Reginald Dyer — the notorious perpetrator of the 1919 Amritsar Massacre in India. One suspects that if living today and with ready access to a computer, John Bowen-Colthurst would be the consummate “internet troll”!

Not content with harassing poor Bird during the latter’s last few years of life, Bowen-Colthurst fired off numerous letters full of rambling rhetoric to local BC papers vigorously attacking the Provincial Wildlife Department’s management practices. He even led a delegation before a legislative committee to protest against the game laws. In mid-1937 he ran for the nascent BC Social Credit League (using the slogan: “A Vote for Bowen-Colthurst is a Vote for B.C.!”) against Premier Duff Patullo in the provincial election. He received just 14 votes out of 2,918 cast in the Prince George constituency! If the hard men back in Ireland were after him, as a veteran IRA man tersely assured BC journalist Jim Hume in a Dublin pub years after his death that they had been, his public profile in the post-Skeena years would surely have made him a sitting duck.

Taylor quotes from a 1930s letter sent to Frank Sheehy-Skeffington’s widow in Dublin by a lady friend — another Irish immigrant — in Victoria who reported seeing Bowen-Colthurst “often at one of the chain store counter restaurants talking to all who would listen.” In her opinion he was “cracked.” Taylor reveals that at one point during this part of his life in distant Western Canada, Bowen-Colthurst bizarrely fantasized about legally suing Frank’s widow Hannah in Ireland for libel. As the author rightly remarks, this shows how the perpetrator of the Easter 1916 Portobello Barracks murders “was still not facing up to the truth.” If one major trait of narcissism is inability to process feelings of deep shame for one’s past malfeasances, then John Bowen-Colthurst surely was a consummate narcissist.

Doug Sutherlin, who as a very young son-in-law found the multi-lingual octogenarian to have tremendous charm and dazzling intellect, observed to Taylor that his late father-in-law could be eccentric, not always in a good way, and “unstable and flighty” with some “crackpot ideas.” For example, by the end of his life, he was a devout believer in “cybernetics,” a fringe economic theory that machines would produce incredible wealth for everyone. Doug remembered his elderly father-in-law, by then living in the Okanagan, trying to distribute free copies of books on cybernetics among doubtless-bemused spectators at Penticton hockey games!

It wasn’t the first time Bowen-Colthurst had done this kind of thing. Taylor mentions how in the 1930s he travelled around B.C. distributing Bibles on behalf of the aggressively evangelical Oxford Group Movement. He had first immersed himself in evangelical Protestantism in the early 1900s in colonial India, and his brief flirtation with BC Social Credit political activism stemmed from his admiration for “Bible Bill” Aberhart, the radio fundamentalist who became Premier of Alberta in 1935. And of course Bowen-Colthurst taking a randomly-selected Bible passage all too literally while unhinged by extreme stress and fatigue in late April 1916, led to the tragic deaths of Frank Sheehy-Skeffington and the other two prisoners at Portobello Barracks.

Given his Protestant Ascendancy family in mostly-Catholic Ireland, religious fundamentalism in Bowen-Colthurst’s no-holds-barred persona was coupled with a lifelong, passionate hatred of Rome’s papal authority. However, his ideological anti-Catholicism didn’t include any trace of bigotry against, for example, the many Hibernian Roman Catholics with whom he served in the mixed-religion Royal Irish Rifles (RIR) during the course of his 18-year military career. Nor — contrary to the claims of at least some of his many demonizers — does his extreme behaviour during the Easter 1916 Rising appear to have been driven even in the slightest degree by his fierce but strictly abstract anti-Catholicism.

Before the 1914-18 War, back from India on “home service” stationed in Co. Down, Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst had come under the influence of Sir James Craig, the Protestant Ulster Unionist strongman leader who would become the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland after Partition in 1922. Perhaps as a result of that association, the ever-impressionable Bowen-Colthurst had risked a serious charge of military insubordination when he had bellowed rudely at his superior officer (the unfortunate Bird, an Englishman just recently placed in command of Irish soldiers).

Bird’s offence, in his junior’s overly-excitable mind, was to mention their regiment’s potential mobilization (which never happened) against the loyalist Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) during the 1912-14 Home Rule Crisis. The UVF, newly armed with smuggled German-made guns, refused to accept the British preference for Ireland to be united under local (home) rule for its domestic policy at least. Bird later remembered this disturbing, if comparatively-minor, sample of Bowen-Colthurst’s capacity for maverick behaviour as a harbinger of much more serious things to come.

In 1939 John Bowen-Colthurst took yet another run at mainstream politics, for the second time in four years angling for the federal Liberal Party electoral candidate nomination in Nanaimo. For the second time, the Nanaimo Liberals chose someone other than Bowen-Colthurst to run. The public mask slipped and Bowen-Colthurst flew into one of his narcissistic rages, accusing them of collusion and chicanery. Thus ended his last attempt at public office, though he retained his Social Credit membership and, for better or worse, continued to be vocal in local community affairs.

In August 1940, at age 59, Rosalinda Bowen-Colthurst, the Captain’s ever-loyal aristocratic Anglo-Irish first wife, died of cancer in Victoria, BC. Most of her estate went to their four adult children, including “Mummy’s Land” in the Skeena Valley. Under the terms of her will her husband was allowed the usage of both that property and “Coolalta” at Milne’s Landing.

He would not be widowed for long — within three weeks of Rosalinda’s death he had proposed marriage by letter to Priscilla Bekman. In early 1941 they were married at Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver.

He had first met Priscilla, his American-born second wife, a Christian missionary teacher, on a solo trip he made to Japan just a few months before Rosalinda’s death. Perhaps Rosalinda had John’s likely remarriage in mind when she made her will: Doug Sutherlin commented to Taylor that he suspected, but could not prove, that his father-in-law had been something of a serial womanizer who hadn’t turned down “opportunities” whenever they arose.

Priscilla, a quarter-century younger than her husband, lived until 1990. In her unpublished memoirs, Taylor tells us, she admitted that she had been wary of marrying a man so much older whom she hardly knew, but on the other hand she had no job to come back home to from Japan, and he needed a wife to look after him. They made for a cosmopolitan couple – speaking around sixteen languages between them, as Taylor notes, and earning extra income during the 1939-45 War by translating documents from BC interior camps where Canadian citizens of Japanese descent were (disgracefully) interned during the global conflict.

This second marriage produced two children, the aforementioned Georgiana (Gee) and a son, Greer, who died tragically aged 14 in an Okanagan Lake drowning accident in 1960. Gee Sutherlin recalled from her childhood how their family home was often filled with guests from different countries, speaking many languages. Gee told Taylor that she had adored her father, and from the record there is no doubt that, for all his flightiness, Bowen-Colthurst was a devoted and loving father to his children. When relaxed among friends he could be a wonderful raconteur, with a great sense of humour. Gee recalled that her mother tended to be “bossy and a troublemaker,” which meant the family had to change church every few years!

Regrettably, neither John Bowen-Colthurst’s first wife’s rapidly declining health in 1939-40, nor his quickly-restored domestic bliss with his second wife in the early 1940s, stopped him from continuing to send the nasty letters to retired Maj-Gen Bird, as well as outrageously-worded missives to various British Government departments ranting about Bird (“that bastard military adventurer”), who had become an obsession for him. Even Sir Anthony Eden, Britain’s Secretary of State for War, got a lengthy rant in the mail from Bowen-Colthurst about Bird.

Another victim, Taylor reveals, was John’s first cousin Elizabeth Bowen, the well-known Anglo-Irish writer. She had the temerity to mention in passing her cousin’s Easter 1916 “fevered and ghastly breach of the rules of war [sic]” in her new (pub. 1942) book about her ancestral family home in Ireland, Bowen’s Court. Reading this passage in Canada, John Bowen-Colthurst erupted with several angry, accusing and very personal letters. Like Bird (who escaped further epistolary retribution by dying early in 1943) Elizabeth Bowen had the good sense not to reply. Two years before his death in 1965 the octogenarian Bowen-Colthurst fired off his last defensive letter to his literary relative, insisting that his 1916 court martial had been a political ploy by British PM Asquith.

In the very late 1940s, the Bowen-Colthursts left Vancouver Island and moved their family home to Naramata in the Okanagan, where the drier climate better suited his bronchitic chest. By then, John Bowen-Colthurst was in his late sixties, father of two young children from his “May-September” second marriage to a much younger woman.

Soon after their arrival in the Okanagan, in typical form Bowen-Colthurst gave a lively luncheon talk to the Penticton Kiwanis Club about the highlights of his early 1900s imperial army career in South Africa, Tibet, and North India. In particular he recalled the Indian Army social life, and the importance of hunting, shooting, and fishing to him and his fellow officers. Small wonder then that he had found very similar recreational opportunities in the remote Skeena Valley so congenial in the 1920s!

Other public activities in his new home locality included vice-presidency of the local branch of the British-Israel World Federation, a movement dating back to the later Victorian era (and still existing today) that held the British to be among the Celto-Saxon direct lineal representatives of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, and the British Royal family to be descended from the Biblical King David. This outer-fringe doctrine seems to have dovetailed neatly with Bowen-Colthurst’s particular brand of messianic religious fundamentalism going back to his days as a young army officer in India. At least during his years in Canada, unlike Dublin in 1916, nobody else got killed because of it.

John Bowen-Colthurst died aged 85 of coronary thrombosis in Penticton General Hospital in early December, 1965. He was buried in the Veterans’ Field of Honour at Lakeview Cemetery, Penticton, wearing his Master Mason’s apron, his casket carried to the gravesite by Freemason pallbearers. A glowing obituary in the local paper made no mention of his part in the Easter 1916 killings.

Taylor concludes that while he may have truly regretted the murders of Sheehy-Skeffington and the others in 1916, it was only insofar as they impacted directly on his own life, not for their drastic effect on the lives of his victims’ surviving families. Through sustained denial, he managed all his remaining life to avoid facing up to the terrible truth and concocted (possibly even eventually believed) a fictionalized version of events in 1914 France and 1916 Dublin. When Jonathan O’Grady gave a presentation on former local resident Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst’s life at the Penticton Museum a few months after e-publishing his and the late Bryan Bacon’s researches, he met several people in the crowd who knew the “old warrior.” They were shocked by what they found out.

One of many British immigrants to have enthusiastically adopted the province as home, and while a marginal figure in B.C. history, John Bowen-Colthurst continues to cast a long shadow in Ireland even fifty years after his death. Earlier this year (2016) on the 100th anniversary of the Easter Rising, the Irish Times reported that “relatives of the victims of the notorious Capt. John Bowen-Colthurst are to seek an apology from the British Government for his actions during Easter Week 1916.”

Among them was the granddaughter of Francis Sheehy-Skeffington.

*

Postscript:

John Bowen-Colthurst’s offspring, among them a respected B.C. Provincial Court Judge (his son Theo or “Paddy,” who died in 1997), contributed in many positive ways to Canadian society, as do his grandchildren to this day.

The Bowen-Colthurst family were also well liked and respected by the local people as fair landlords in pre-1916 Co. Cork, where the family had deep roots running back through many generations.

In Mark Bence-Jones’ Twilight of the Ascendancy (1982), in the chapter “Terrible Beauties” — the title taken from the famous W.B. Yeats poem about the Easter Rising — is a passage about the IRA burnings of various Anglo-Irish mansions including Oakgrove, John Bowen-Colthurst’s childhood home:

After Oakgrove was burnt [in July 1920], Bowen-Colthurst’s unmarried sister, who had been living there with her mother, received a message telling her to go to a mysterious address in Cork city. There, in an upper room, she found an Alladin’s cave of jewellery from various country houses; she was told to take away whatever was hers and her mother’s.

Ireland is indeed a land of nuances — a place “where ambiguity plays so active a mediating role in human relations,” according to Joseph J. Lee, the Co. Kerry-born historian and author of Ireland, 1912-1985: Politics & Society (1989).

*

Joe Simpson is a longtime family lawyer who writes from Vancouver Island. Born in Northern Ireland, he graduated with first class honours in modern history from Cambridge University in 1973. After a spell teaching in Asia, he worked in the international deep-sea energy shipping industry in London, England, for twelve years before seeing the light and immigrating to B.C. in 1988. A UBC law degree followed, since when he and his wife Penny have lived in the Cowichan Valley along with numerous dogs and cats. He still keeps in touch with his Cambridge history mentor, Prof. Joe Lee, now in New York City.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of BC books and authors in all fields and genres. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Kathy Mezei, Patricia Roy, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

3 comments on “#63 An Imperial crackpot in BC”

Fascinating read, I wonder if there’s a family connection with the Colthurst family in Blarney Castle Co Cork

Neil Molloy

There is!

Wow! fantastic review of a book I will now undoubtedly purchase, thank you.

Comments are closed.