#40 Windy Arm, Tutchi, Tagish Lake

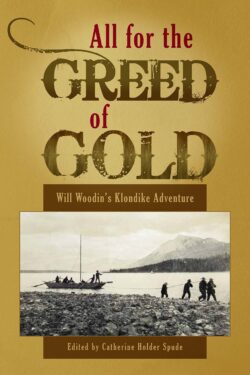

All for the Greed of Gold: Will Woodin’s Klondike Adventure

by Catherine Spude (editor)

Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 2016

US $27.95 / 978-0874223354

Reviewed by Robert G. McCandless

First published November 9, 2016

*

Our history of the past 100 years seems so dominated by wars and their consequences that we have forgotten the scale of the defining event in northwest North America in the late nineteenth century—the Klondike Gold Rush.

Our history of the past 100 years seems so dominated by wars and their consequences that we have forgotten the scale of the defining event in northwest North America in the late nineteenth century—the Klondike Gold Rush.

A new book, edited by Dr. Catherine Spude, should help explain why tens of thousands of men and more than a few women embarked on a single adventure that sometimes defined their lives.

Publication of All for the Greed of Gold: Will Woodin’s Klondike Adventure was sparked when Spude recognized the historiographical value of a century-old manuscript memoir and an incomplete diary, neither of them previously published. She presents these in parallel, with introductions and marginal notes helpful to today’s reader.

This book’s greatest value lies in its details on prices, wages, and trading, which together illuminate the era’s mercantile economics. As well, scholars of the Klondike Gold Rush will value the veracity of Will Woodin’s account and its unexpected nuggets, such as the revelation that customs officials were open to accepting the odd bribe.

Born in 1874 into a homesteading family in Michigan, Woodin’s family moved to Seattle in 1890 and worked in the lumber business. The news of the Klondike discovery reached Seattle almost a year after the original 16 August 1896 discovery, and Woodin’s extended family and friends decided to join thousands of people, in the United States as in Canada, who decided to join or invest financially in the gold rush.

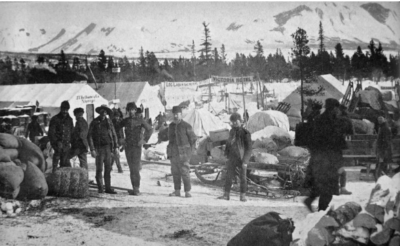

After landing from their steamship in Skagway, the stampeders faced a 60-kilometre trek up the infamous Chilkoot Pass (or the adjacent White Pass) and over the Canada-US border and on to Bennett Lake. This was a dangerous and exhausting journey, made on foot in winter conditions.

At the border, Canadian police inspected the Woodin party’s goods to ensure that they had sufficient food and supplies to maintain each man for a year — about 1500 pounds (700 kg) in total.

Woodin, then 24, his father, and the three others in their party were as keen as anyone to find placer gold, but they were also astute planners who carried extra goods to sell and thereby offset part of the capital they invested in their journey. Spude estimates that they carried nearly five tons of crates, packages, and tools.

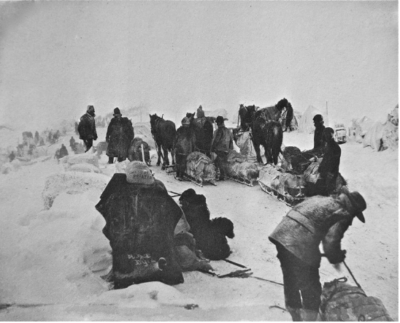

Sleds pulled by two horses brought their goods into Alaska and moved their outfit with repeated shuttling between temporary caches. When insufficient snow or a bad trail made sled travel impossible, the men carried their goods on their backs.

Notoriously, hundreds if not thousands of horses used by stampeders were abandoned or slaughtered on the trails. Woodin was proud that his horses survived the ordeal.

The importance of All for the Greed of Gold lies in its close description of the “Too Schi” (Tutchi) Trail from White Pass and Log Cabin to Windy Arm on Tagish Lake. These sites are in British Columbia, pinched between southeastern Alaska and the part of Yukon Territory that included Bennett Lake, the stopping point for the majority of travellers who used the shorter and steeper Chilkoot Pass.

The Windy Arm trail was longer but ended at a site with better timber for boat building. The Woodin party’s feat in packing their five-ton outfit over a 90 km (60 mile) trail seems incredible, but Woodin explains that hundreds of others made the same journey, and he never stoops to boast that their achievement was in any way exceptional.

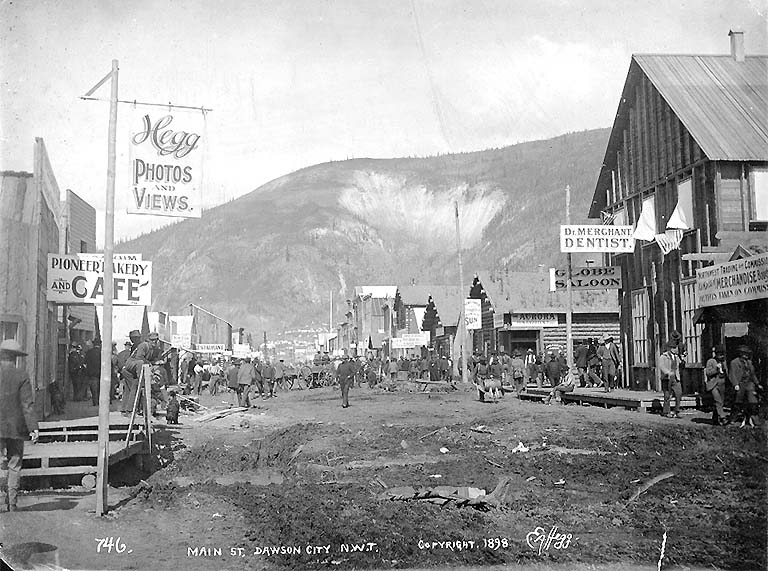

At Windy Arm, in May 1898, they built two large boats and two skiffs from planks sawn by hand from local timber. On 29 May, the ice on Tagish Lake went out and all boats set out downriver to Dawson City. They stopped at Tagish Narrows to have their outfits checked by the police, then sailed and rowed to the start of the Yukon (Lewes) River at the outlet of Marsh Lake.

They drifted safely through that river’s last serious obstacles, Miles Canyon and Whitehorse Rapids and on 8 June resumed their downstream voyage.

Part way to Dawson, at Little Salmon, they cached their boats and outfit and trekked overland for days, chasing rumours of a gold strike near the Pelly River. This fruitless quest delayed their arrival in Dawson City by almost a month.

At Dawson, they visited the gold creeks and prospected some new ground which was not, however, promising. They were uncertain of remaining in Dawson over the winter when Will became seriously ill from typhoid, a disease that had became an epidemic in this instant town.

Woodin’s father then sold their remaining outfit, and with Will now an invalid, booked them aboard a steamboat for the upstream passage to Whitehorse and Bennett. From there, after a difficult journey on horseback, Will and his father reached Skagway, Alaska, from which a ship took them back to Seattle, where the narrative ends.

Spude argues that Will’s adventure, when combined with those of hundreds if not thousands of other stampeders, marks the appearance of a new mercantile class derived from the farmers who first settled (i.e., colonized) the North American west.

This may be a fruitful multigenerational way of viewing Gold Rush participants, but of greater interest to me is how those with capital in both Canada and the US, with greatly different views of trust and risk, willingly grubstaked others — miners, merchants, professionals, shipbuilders — to join the Klondike quest with the odds of individual success little better than a common lottery.

In those days, people seem to have regarded capital as something almost alive and deserving nimble and venturesome investment.

Will Woodin writes well and the book is engaging, but its production and editing occasionally fall short. The Lewes River (an upstream reach of the Yukon River) is incorrectly named “Lewis.” One of its maps needs a scale, and all the maps could have been better drawn to impart a sense of the mountainous terrain. Another dozen or so contemporary photographs would have added greatly to the book’s appeal.

Despite these omissions, All for the Greed of Gold: Will Woodin’s Klondike Adventure is a useful introduction to the Klondike Gold Rush and a satisfying and informative read for anyone interested in this great defining late nineteenth century cross-border adventure.

*

Robert McCandless practiced as a geologist until his retirement in 2009 after 28 years with Environment Canada. Previously he worked in oil and gas exploration and mining. For several years when he lived in the Yukon Territory his work as a researcher led to his publishing Yukon Wildlife: A Social History (University of Alberta Press, 1985). With government, he worked on environmental issues in the mining sector, and also advised on Aboriginal affairs including northern Canada and BC treaty negotiations. Since retirement he has published on natural resource and history topics including BC Offshore petroleum exploration before the current “moratorium” (BC Studies No 178, summer 2013); and Britannia Mine pollution (BC Studies No 188, Winter 2015/16), and continues historical research and writing. He lives in Delta BC.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster

One comment on “#40 Windy Arm, Tutchi, Tagish Lake”

Comments are closed.