#59 From Civil Gothic to Modern

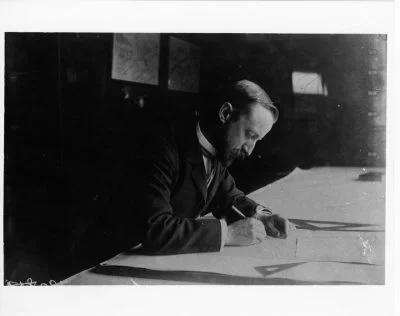

Thomas Fuller: Architect for a Nation

by Dorothy Mindenhall

[Victoria:] Lakehill Books, 2015

$45.00 / 9780994809513

*

Imagining Uplands: John Olmsted’s Masterpiece of Residential Design

by Larry McCann

[Victoria:] Brighton Press, 2016

$55.00 / 9780995066304

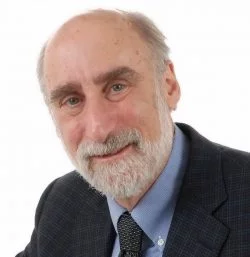

A joint review by Harold Kalman

First published Dec. 6, 2016

Two stimulating additions to the literature on the Canadian built environment have recently come out of Victoria. Both are worthy of close reading and both, interestingly, were privately printed.

This seems to say lots about the reluctance of both commercial and university presses to take on architectural titles. It certainly advances the self-fulfilling truism that architecture books don’t sell in Canada, as well as the widely held belief that Internet publishing has less value than the printed book.

The two books under consideration reveal contrasting approaches to book-writing and book-making. Dorothy Mindenhall’s monograph on Thomas Fuller (1823-1898) is a characteristic product of architectural history, whereas Larry McCann’s study of the Uplands neighbourhood, near Victoria, is a lavish presentation of the geographer’s craft.

Mindenhall’s treatment focuses on Thomas Fuller and his oeuvre, mostly chronologically, from his youth in Bath, England, to his death in Ottawa. His first building, the Late Georgian St. John’s Cathedral, Antigua (1847), commissioned when Fuller was in his early twenties, already reveals a penchant for monumentality and superb siting. It also introduced Fuller’s ability to stir controversy, as the British journal, The Ecclesiologist, dismissed the cathedral as a “mere overgrown Pagan church … with two dumpy pepper-box towers.”

Fuller and his young family immigrated to Toronto in 1857 in search of the opportunities offered by the New World. His skills at self-promotion soon paid off, and within months he found an important client, R.B. Denison, who retained him to design St. Stephen-in-the-Fields Anglican Church (1857), one with which The Ecclesiologist would have been far happier.

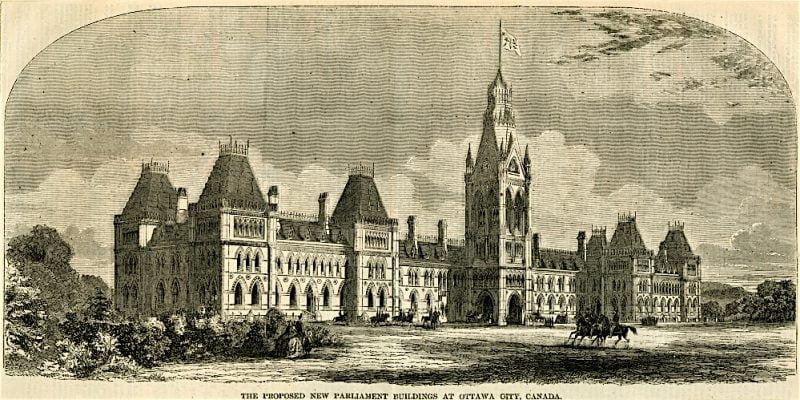

Two years later Fuller teamed up with Canadian Chilion Jones to enter the competition for the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa. The design and siting of Fuller and Jones’s Centre Block (begun 1859, destroyed by fire 1916) and Stent and Laver’s East and West Blocks are sublime; the late and highly respected American architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock gushed that “the variety of form, the gusto of the detail, and the urbanistic scale of this project made [it] a major monumental group unrivalled for extent and complexity of organization in England.”

The Centre Block may have excelled in its High Victorian “civil Gothic” design, but the execution was problematic and forced the appointment of a Commission of Enquiry. Mindenhall relates the familiar story of “mismanagement, overspending, corruption, differing interpretation of roles … and time spent on unrealized projects.”

A similar scandal occurred a few years later at the New York State Capitol in Albany, when Fuller and his new partner, Augustus Laver, were dismissed as architects after only a few years. The author cites the events as well as the buildings, showing Fuller’s design strengths, but shies away from focussing on his obvious faults as a professional practitioner.

Despite the grief over the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, Fuller was later appointed Chief Architect of the Department of Public Works, a position he held for sixteen years, retiring a year before his death.

In this capacity he supervised the construction of federal buildings from coast to coast, ranging in scale from the large Langevin Block in Ottawa (1883) — sometimes considered the South Block of the Parliament Buildings — to the modestly scaled, but robust, former Post Office in Baddeck, Nova Scotia (1885). His post offices also included those at Nanaimo (1883, demolished 1954) and Victoria (1894, demolished 1956).

Fuller also maintained a more modest private practice, whose output included the Gothic Revival church of St. Stephen-in-the-Fields, Toronto (1857), and the equally Gothicized residence of Ezra Cornell in Ithaca, New York (1867). He showed a facility with a range of eclectic design vocabularies of the Victorian era and had penchants for self-promotion and making the big statement.

Despite Fuller’s renown, this is his first monographic treatment and therefore a welcome newcomer to the bookshelf. The book is a pleasure to read. Its descriptive and critical text breaks new ground, particularly with the extensive list of Fuller’s projects, which contributes significantly to our knowledge. It is well designed and printed, yet unassertive in its presentation. The generous illustrations feature exterior views and some interiors — although, unfortunately, no floor plans — which are well reproduced in both black-and-white and colour. The paperback binding helps to keep the price affordable.

*

Larry McCann’s striking book on Uplands, by contrast, features graphic design, 80-pound paper, and a hardcover binding that produce the look and feel of a limited edition. A colophon identifies the designer, artist (of numerous pencil drawings), typefaces, and printer.

The pages display a variety of graphic devices, most notably a peacock feather, which serves as a metaphor for the picturesque and decorative qualities of the Uplands design.

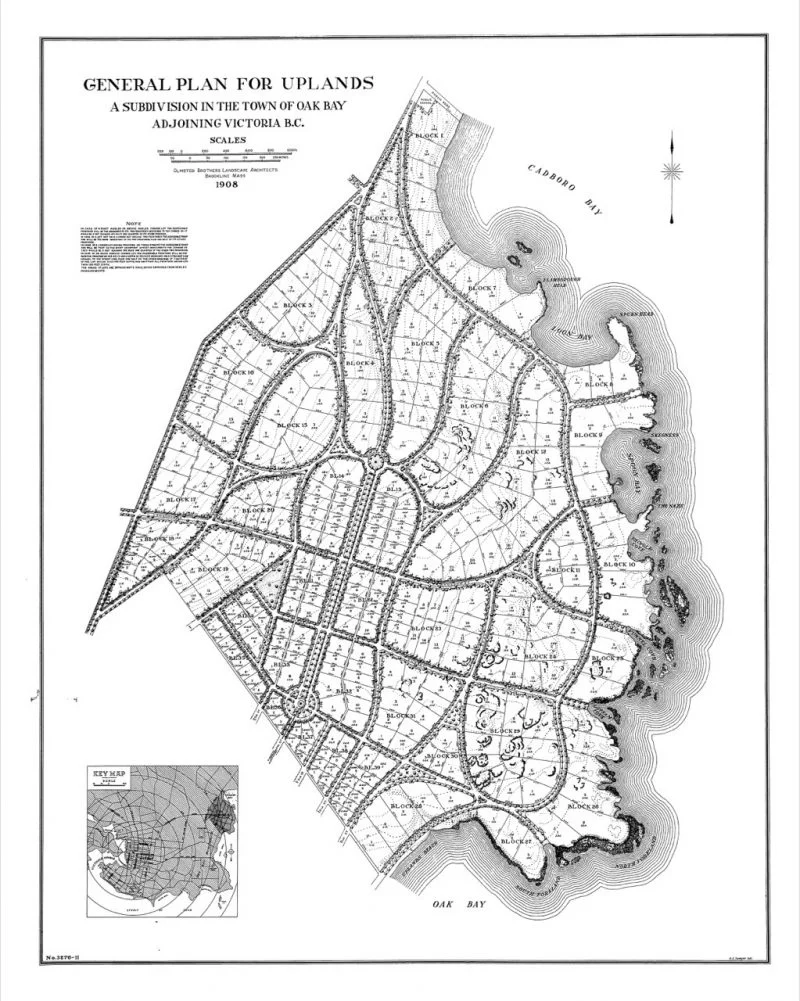

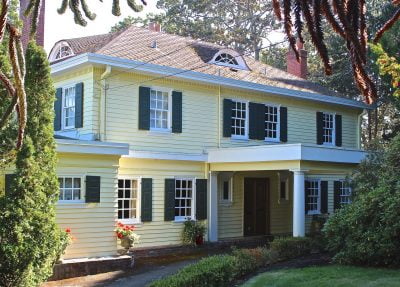

McCann taught for many years in the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria, and his approach is aptly that of the retired historical geographer. He leads the reader on a leisurely ramble through Uplands, a residential subdivision in Oak Bay, adjacent to Victoria (“imagined” in 1907), which was promoted as “Victoria’s Celebrated Residential Park.”

The author reveals a keen understanding and appreciation of the nature of the neighbourhood and the people who created it. He focusses on the professional relationship between the ambitious but inexperienced developer, Winnipeg financier William Hicks Gardner, and the landscape architect, John Charles Olmsted, a partner in Olmsted Brothers of Brookline, Massachusetts. John was the nephew and, later, stepson of the celebrated Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park in New York and Mount Royal Park in Montreal.

The elder Olmsted dismissed young John’s allegedly indifferent artistic abilities, asserting that “a man of less artistic impulse I never knew.” The lad’s mother lamented that “John is John & must be taken as he is made … most excellent and clumsy” (pp. 25, 31). Having to endure parental criticisms such as these, however they may have been based, the younger Olmsted could not help but grow up with a sense of inferiority.

With this in mind, the reader is left to wish for a more critical analysis of Olmsted’s output and his position relative to his self-image and the perceptions of his peers and critics, an approach that would adopt the methodology of the art historian more than that of the geographer. (Full disclosure: the reviewer was trained as an art historian.) The book sets out to demonstrate “why Uplands is a masterpiece of residential design” (p. 15; “masterpiece” also appears in the subtitle), but does not demonstrate with any rigour whether or not this was so.

We are reminded that Uplands was laid out along “artistic and naturalistic lines,” and indeed, this is its essence. The highly irregular plan respects the varied topography by introducing curved streets, roundabouts, and Y-intersections. This style, derived from the picturesque aesthetic of English landscape architecture, was adopted in the U.S. by Frederick Law Olmsted and contrasted with both the common gridiron city plan and the grander, more formal, City Beautiful style associated with Daniel H. Burnham.

The naturalistic manner was continued by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and his stepbrother, Uplands’s designer John C. Olmsted. McCann introduces some other town plans of the day, such as Rickson Outhet and Frederick Todd’s Tuxedo Park, Winnipeg, conceived in 1905, in which Olmsted became involved five years later, but a more generous survey and analysis of comparable plans could have established the extent to which Uplands was indeed a masterpiece.

The intricate social, political, and financial contexts of the Uplands development are central to the text. Gardner was overstretched and could not maintain control over the development, and so he sold his interests in the Uplands property in 1911 to the Franco-Canadian Corporation, which was financed with money from France. Gardner’s syndicate reacquired partial ownership about a decade later, when the new owners fell into default.

The narrative brings the design and business processes to life by recreating activities, conversations, and thoughts from letters and other sources, which are identified in endnotes. Nevertheless it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between “fact” and well-informed hypothesis. The organization of the book is rather fluid, but a thorough index facilitates making reference to particular subjects.

The McCann and the Mindenhall books will both have enduring value as good (if academic) reads and lasting references. It is disappointing that the publishing industry could not have had the farsightedness to encourage the authors, take on the titles, and give them the distribution that they deserve, and it is regrettable that Canadian readers of architectural books do not assert themselves more strongly at the bookstore.

*

Harold (Hal) Kalman is a heritage planner and architectural historian living in Victoria. He divides his work time between writing and teaching. He recently withdrew from an active international consultancy in heritage conservation after 35 years in practice, including extensive work in China. Kalman teaches heritage conservation at the Universities of Hong Kong and Victoria. He is the author of many books and articles for both professional and general readers, including Heritage Planning: Principles and Process (Routledge, 2014) and A History of Canadian Architecture (2 vols., Oxford, 1994). Kalman was the founding president of the Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals and is the British Columbia member of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. He received the B.C. Heritage Award in 2006, the Gabrielle Léger Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Heritage Conservation in 2009, and Lifetime Achievement Awards from the City of Vancouver (2013) and the Canadian Association of Heritage Professionals (2015). He is a member of the Order of Canada.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Readers. More Reviews. More Often.

Reviews Editor: Richard Mackie

Reviews Publisher: Alan Twigg

The Ormsby Review is hosted by Simon Fraser University.

—

BC BookWorld

ABCBookWorld

BCBookLook