#51 Cow men, cowboys, vaqueros

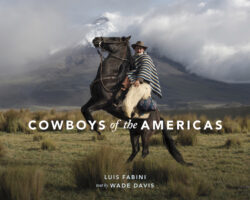

Cowboys of the Americas

by Luis Fabini (photographs) and Wade Davis (text)

Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2016

$50.00 / 9781771641166

Reviewed by Ken Mather

First published Nov. 27, 2016

*

Cowboys of the Americas dwells on the distant origins – southern Spain and Spanish America – of the vaqueros or cowmen of the grasslands of the Americas.

Reviewer Ken Mather assesses this wide-ranging portrayal by Luis Fabini and Wade Davis of a ranching culture that extends deep into the BC Interior — Ed.

*

Cowboys of the Americas offers a significant collection of photographs of those who look after cattle in the Americas, especially the little-documented cattle cultures of South America. I recommend this book highly as an excellent photographic study of the working “cow men” of these fascinating cultures of the Americas, particularly the cattle cultures of South America. Indeed, Fabini’s images of the men of the saddle are well worth the price.

Cowboys of the Americas offers a significant collection of photographs of those who look after cattle in the Americas, especially the little-documented cattle cultures of South America. I recommend this book highly as an excellent photographic study of the working “cow men” of these fascinating cultures of the Americas, particularly the cattle cultures of South America. Indeed, Fabini’s images of the men of the saddle are well worth the price.

That said, the title of the book, Cowboys of the Americas, stopped me short because the term “cowboy” has only ever referred to the ranch hands of the US and Canada and has taken on stereotypes that border on mythology. I would have preferred something more generic, like “cow hands” or, better yet, the Spanish term, vaquero, which translates in English as “cow man” and was used for the first mounted herdsmen in southern Spain who were the ancestors of all those who look after cattle in the Americas.

In the photographer’s introductory vignette, Luis Fabini declares that “I went in search of the cowboys of the Americas and found extraordinary ‘centaurs’ who share a powerful bond with the land and with their animals — and whose only allegiance is to hard work and absolute freedom.”

Following this, I expected the book to focus on the lives of these men who spend their lives on the cattle ranges of the Americas. While Fabini’s photographs brilliantly capture the men, animals, and settings, the accompanying text by Wade Davis in many places is weakened by cliché and at times inaccuracy and questionable relevancy.

In the opening section, “Of Horses and Men,” Davis describes the “cowboys” he met in northern B.C. as “men who lived where their hat fell, rough-cut diamonds who worked the hunting camps all fall, drank away their earnings in a weekend, and retreated to the line camps of the Chilcotin far to the south to tend cattle through the long and impossible winters of the Interior.”

Such a description does little justice to the full-time cowboys of B.C. who, at the top of the year, would be involved in the fall activities of roundups and cattle drives. Instead we are given a stereotype of the “cowboy” rather than an insight into the men whose photos so powerfully fill this book.

While the photographs aptly depict these “men of the saddle,” this part of the introduction only perpetuates the stereotypes, while providing little detail of the everyday life of those who earn their living caring for cattle.

True to his background in anthropology, Davis goes on to describe the evolution of the horse and mankind. While interesting and well written, this is only partly relevant to the photographic content of the book. It takes eleven more pages for the horse to arrive in the Americas and seven more before the lowing cloven-hoofed herds are introduced to the three-way connection of men, horses, and cattle.

In the process, some contentious statements are made without explanation or footnotes. Davis states that “the American forces in the west were given explicit orders to ‘kill every Indian in the country’” (p. 23), and that “Government policy was explicit: exterminate the bison and destroy the native cultures” (p. 25).

But no sources are cited for these debated and controversial statements. Robert Wooster, who deals with this issue in his excellent book, The Military and United States Indian Policy 1865-1903 (University of Nebraska Press, 1995) concludes that “The army, while anxious to strike against the Indians’ ability to continue their resistance, did not make the virtual extermination of the American bison part of its official policy; in some cases, individual officers took it upon themselves to try and end the slaughter.”

Davis also asserts that, “As a way of life [the cowboy culture] had its beginnings in the most remote reaches of the Spanish colonial realm, in land that would be known as Texas.” Actually, the way of life can be traced back to Southern Spain, where mounted men first began to herd cattle.

The Spanish vaqueros brought this culture to the New World, modified and adapted the tools of the trade to their specific needs and climate, and then extended the culture throughout North and South America. In the United States alone, there were two distinct cattle cultures, one originating in Texas and the other in California, both of which spread northward.

Davis describes the cattle drives out of Texas from 1866 to 1886 as the “golden age of the American cowboy.” Yet during this time, descendants of the vaquero were developing distinct cattle cultures in other areas of the Americas. West of the Rockies, a distinct “buckaroo” culture, based upon the vaquero, was evolving as were the other cattle cultures of South America and Mexico — all independent from what was going on in Texas.

Once this lengthy and only partly relevant opening is completed, Fabini and Davis settle down to portray the different ranching cultures of South and Central America.

The highlights of the book are the photographs and Davis’s brief introductory descriptions of the South American cowhands. These depict the settings, the men, and the animals with sensitivity. Aside from occasional flaws, such as the strange assertion “that cattle do not swim” (p. 66), Davis’s all-too-brief introductions provide useful preludes to the stunning photographs.

The chapters devoted to the United States and Canada are less compelling, probably because most North American readers have been exposed to many images of the working cowboy. Numerous good photographic studies, such as the excellent Gathering Remnants: A Tribute to the Working Cowboy, by Kendall Nelson and Felicitas Funke-Riehle (Prairie Creek Productions, 2001), have set a very high bar.

While Fabini’s photographs are excellent, the introductory texts — ranging from the lack of available water in the US cattle country to the demise of the family ranch in western Canada — do little to inform or enhance the photos. A closer editorial hand, perhaps, would have provided greater congruency.

*

Ken Mather retired in 2013 after 42 years in heritage site research, planning, administration, and management. He was Manager/Curator of the Historic O’Keefe Ranch near Vernon from 1984 until 2004, and remained as Curator for the next ten years. Ken has written a large number of articles and research reports on early ranching in British Columbia for different magazines and websites. He is author of three recent histories of ranching and ranching cultures in the Canadian west, all published by Heritage House: Buckaroos and Mud Pups: The Early Days of Ranching in British Columbia (2006), Bronc Busters and Hay Sloops: Ranching in the West in the Early Twentieth Century (2010), and Frontier Cowboys and the Great Divide: Early B.C. and Alberta Ranching (2013). His self-published Ranch Tales (2014) is a compilation of his columns in the Vernon Morning Star. Ken was recognized as the Curator Emeritus of the O’Keefe Ranch in 2013 and was awarded the Joe Martin Memorial award for his contribution to BC Cowboy Heritage in 2015.

*

The Ormsby Review. More Books. More Reviews. More Often.

Publisher and Editor: Richard Mackie

The Ormsby Review is a journal service for in-depth coverage of B.C. books and authors. The Advisory Board consists of Jean Barman, Wade Davis, Robin Fisher, Cole Harris, Hugh Johnston, Patricia Roy, David Stouck, Maria Tippett, and Graeme Wynn. Scholarly Patron: SFU Graduate Liberal Studies. Honorary Patron: Yosef Wosk. Provincial Government Patron since September 2018: Creative BC

“Only connect.” – E.M. Forster